A new study was released today that says if you give poor mothers extra money, their babies have slightly improved brain development. Brendan Nyhan is skeptical:

I really hope this is true but it's one paper, p=.02 with largest outcome added after preregistration, main result uses a post hoc combination of measures, and acknowledged sensitivity of results to differences between groups. Let's wait and see. https://t.co/uOUXLz8VnN

— Brendan Nyhan (@BrendanNyhan) January 24, 2022

OK, sure, but there's already a long literature showing a correlation between poverty and infant brain development, so this paper's result isn't very surprising. You might even wonder why anyone bothered with this particular bit of research.

There are two reasons. First, instead of just measuring poverty it makes use of "giving people money," which is a hot topic in lefty circles these days. Second, and more important, it doesn't use mere survey or test data. It involved hooking up babies to EEG machines and measuring their brainwaves, which is much more sciencey.

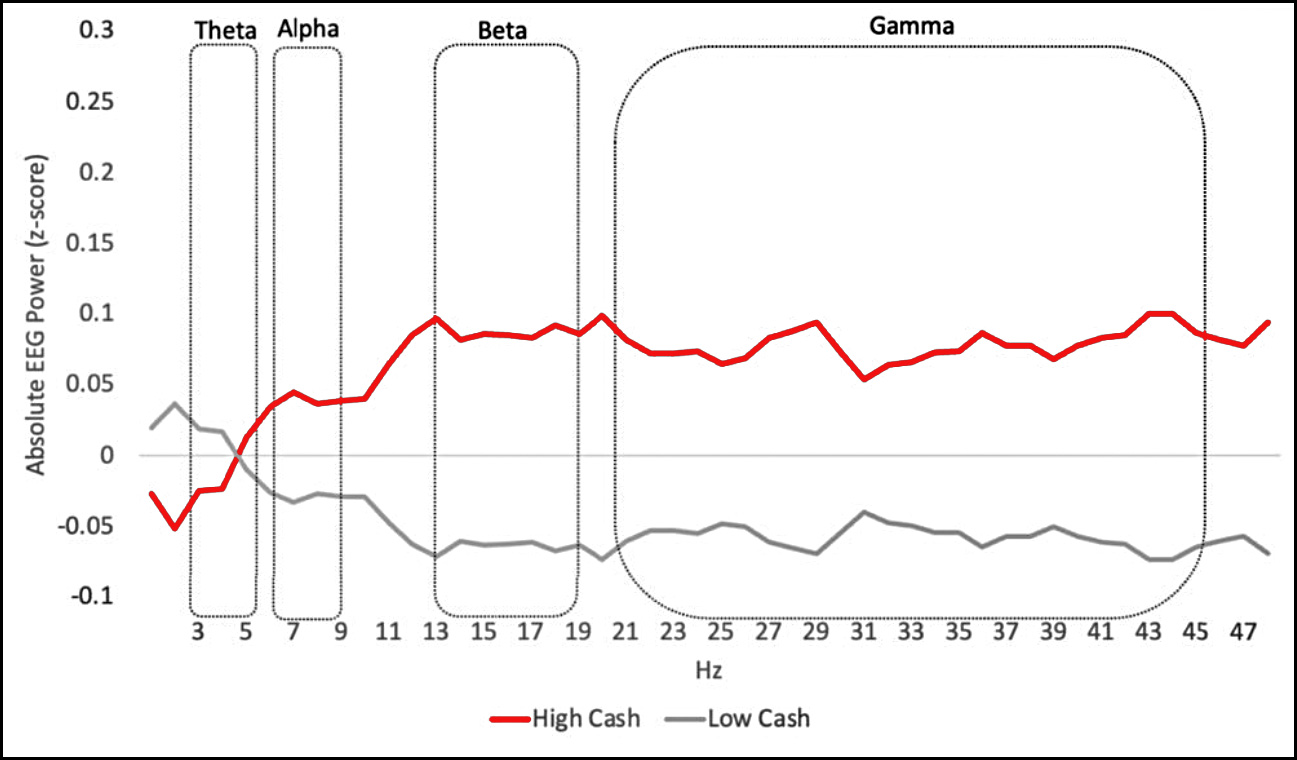

This surprised me because I had never heard of it before, but it turns out that we've been hooking up babies to EEGs for a long time and measuring various Greek letters:

Childhood EEG-based brain activity demonstrates a specific developmental pattern....For example, more absolute power in mid- to high- (i.e., alpha, beta, and gamma) frequency bands has been associated with higher language, cognitive, and social-emotional scores, whereas more absolute or relative low-frequency (i.e., theta) power has been associated with the development of behavioral, attention, or learning problems.

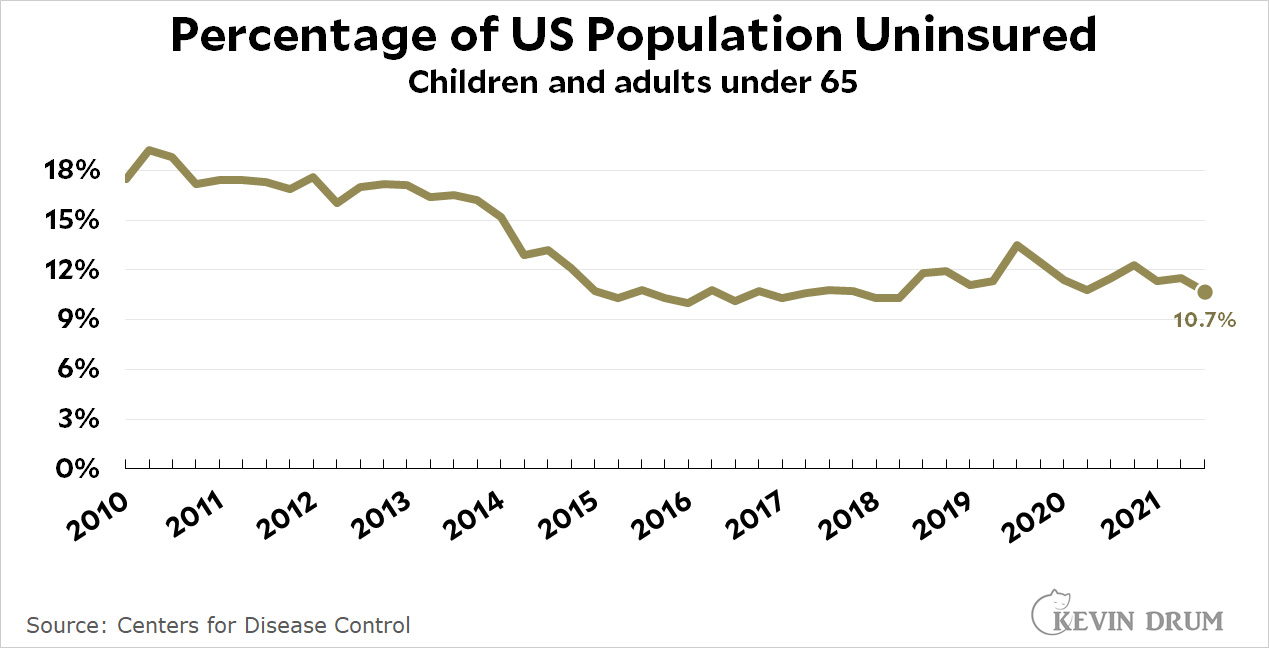

This sounds vaguely new-agey, but I guess it's accepted science: beta and gamma are good; alpha is mixed; and theta is bad.¹ Here's a chart from the paper showing what happens to the children of mothers who were given the extra money:

Sure enough, the kids who got the extra money have higher beta and gamma responses. For now, then, let's assume these measurements were correctly done. The key question is whether increased EEG activity in the beta and gamma bands is truly correlated with stronger cognitive development later in life. The entire study hinges on this.

Sure enough, the kids who got the extra money have higher beta and gamma responses. For now, then, let's assume these measurements were correctly done. The key question is whether increased EEG activity in the beta and gamma bands is truly correlated with stronger cognitive development later in life. The entire study hinges on this.

So I took a look. The first problem I ran into is that most of the infant brainwave studies are related to autism research. Apparently peak alpha activity is associated with symptoms of autism, and research into this is ongoing.

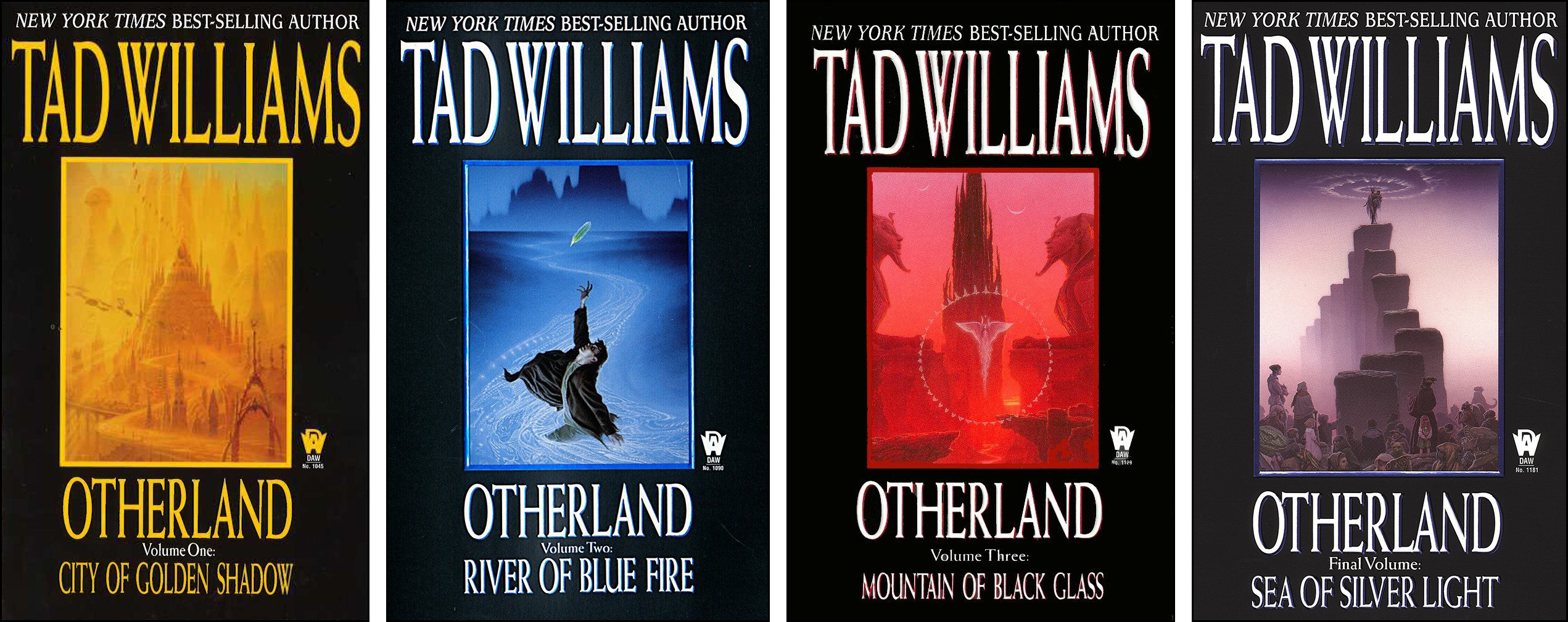

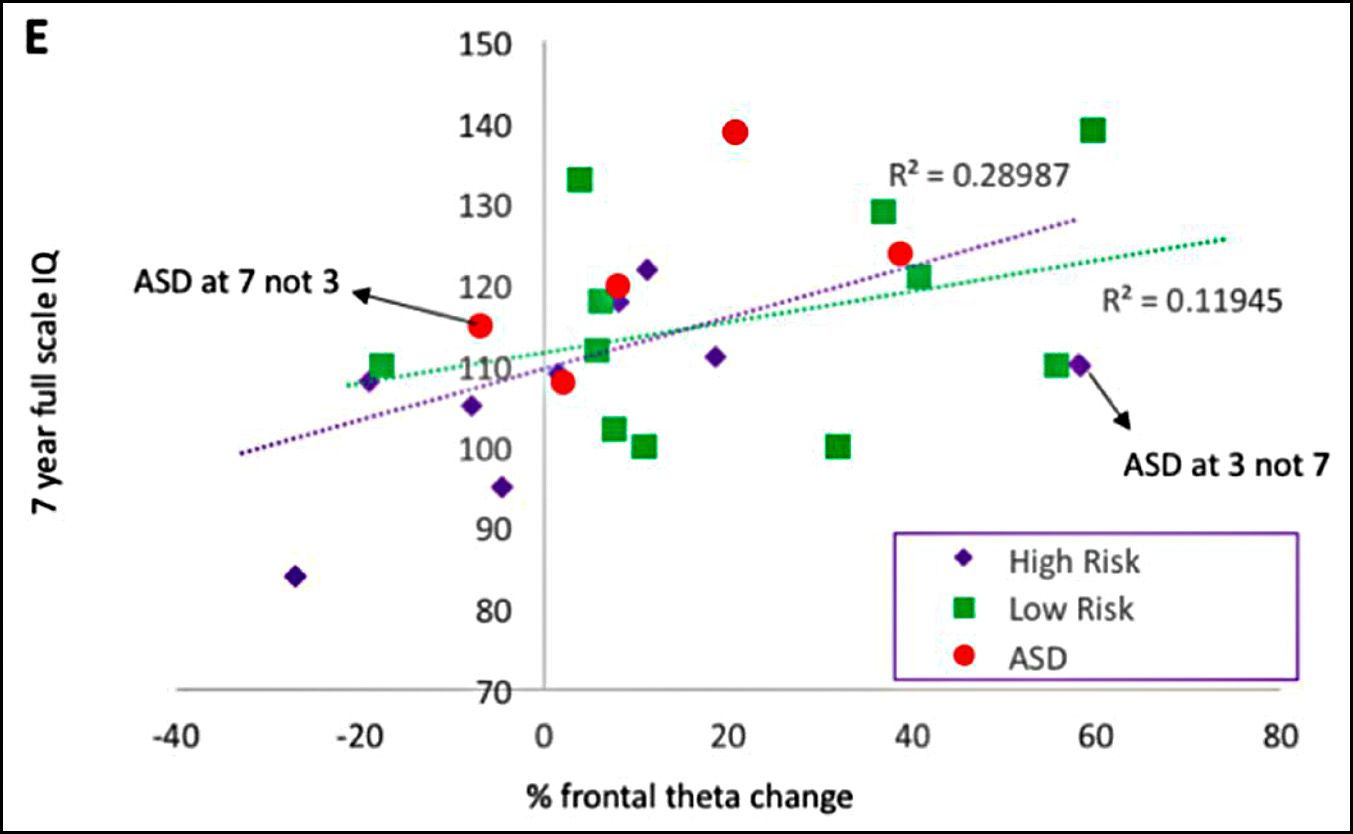

That's obviously not germane to poverty, so I had to restrict my search to studies that weren't about autism. There weren't many longitudinal studies that tested kids beyond about two years old, but here's one that went out to seven years old:

Meh. The sample size is tiny; the trendline looks awfully dependent on one outlier kid with an IQ of 140; and there are hardly any kids with an IQ below 100, which suggests this was not a very random sample.

Meh. The sample size is tiny; the trendline looks awfully dependent on one outlier kid with an IQ of 140; and there are hardly any kids with an IQ below 100, which suggests this was not a very random sample.

There are other studies that measure a variety of things, but I couldn't find any that measured medium-term life outcomes against infant EEG results. There's a fair amount of evidence that EEG results are correlated with improved cognitive skills at around age two, but not much beyond that.

At least, that's my horseback conclusion. I might have missed some studies. For now, though, I'd advise skepticism until someone does a rigorous longitudinal study, which would obviously take a long time.

In the meantime, it's probably true that poverty is associated with poor brain development. This new study doesn't offer much that's new on that score.

¹The reason this surprised me is that apparently EEG studies of infants have been going on for a long time, but we nonetheless haven't been inundated with sketchy books about "how to improve your baby's gamma waves" or Dr. Oz segments about dietary supplements that will depress alpha waves. Where are the cranks and crackpots in all this?