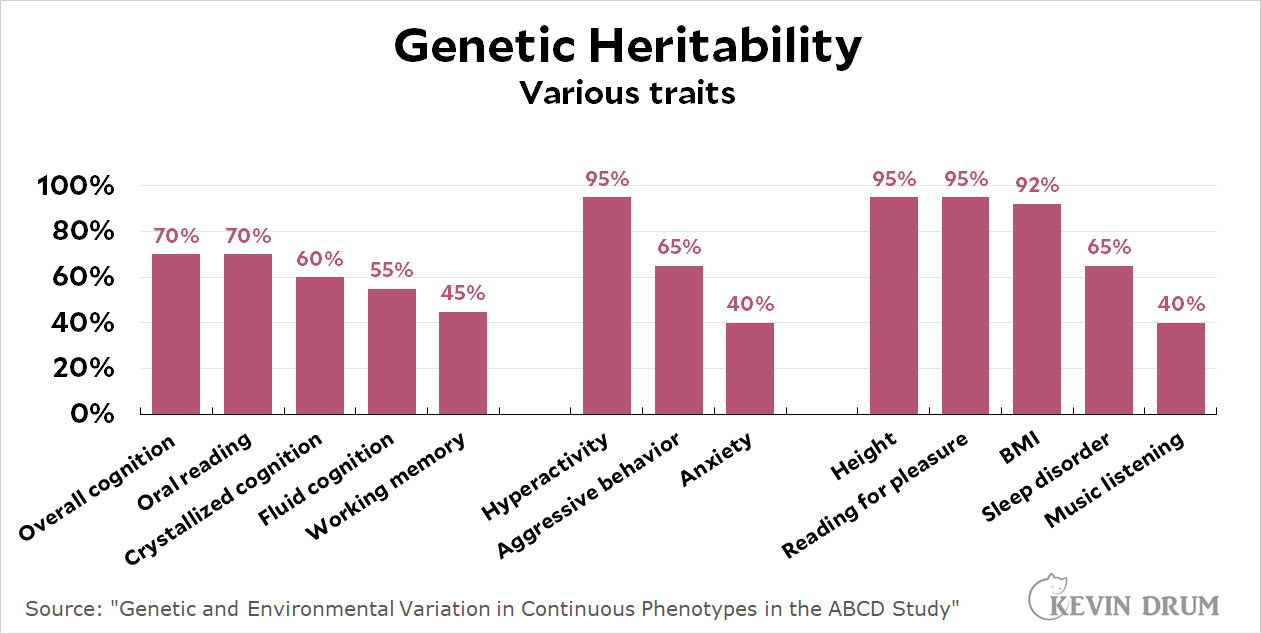

A newly published study in Behavior Genetics describes the genetic heritability of a vast number of traits based on measurements of 772 pairs of twins (half identical, half not). The basic concept here is that if a trait is largely genetic, it will be more closely shared by twins who have identical physical and cognitive characteristics. Conversely, non-identical twins will inherit only smallish and random bits of each trait.

The study incorporates thousands of traits, most of them related to brain volume and structure based on imaging studies. However, it also includes quite a few of more general interest. Here's a selection:

Overall cognition, which is basically intelligence, is about 70% inherited. The other 30% is influenced by shared and non-shared environment. The same is true for oral reading. The subcomponents of intelligence, fluid and crystallized cognition, are a bit less inheritable.

Overall cognition, which is basically intelligence, is about 70% inherited. The other 30% is influenced by shared and non-shared environment. The same is true for oral reading. The subcomponents of intelligence, fluid and crystallized cognition, are a bit less inheritable.

Hyperactivity is almost entirely inherited. Anxiety, by contrast, is only weakly inherited. It's apparently caused mostly by environmental factors.

Reading for pleasure is almost entirely influenced by genes. Oddly, though, listening to music isn't.

Thanks to the size and breadth of this study, it's basically state-of-the-art among classical twin studies. More modern GWAS studies will likely supplant it in years to come, but so far they've surveyed only 15-20% of the human genome. For now, this is about as good as it gets.