Tyler Cowen weighs in today on a study of the lead-crime hypothesis:

These results seem a bit underwhelming, and furthermore there seems to be publication bias....I have long been agnostic about the lead-crime hypothesis, simply because I never had the time to look into it, rather than for any particular substantive reason. (I suppose I did have some worries that the time series and cross-national estimates seemed strongly at variance.) I can report that my belief in it is weakening…

Hmmm. I suppose that a quick look at the abstract of one paper might very well weaken your belief in something if it's the only thing you've ever looked at. Unfortunately, even mild pronouncements from Tyler tend to carry a lot of weight, so I suppose I should comment on this even though I'm sort of tired right now and don't really feel like it.

But let's do it anyway! I shall sprinkle exclamation points throughout this post in order to simulate energy and enthusiasm. But I'm afraid it's going to be kind of long and boring anyway. That's just the nature of these things. If you want to read along, the study is here.

First, though, just to get this out of the way: I don't know what Tyler means when he says "the time series and cross-national estimates" are at variance. I've looked at both and they seem to agree fine. Time series estimates tend to show that crime goes up and down based on lead levels in the past (i.e., during childhood), while cross national estimates tend to show that the peaks and troughs of crime line up with the rise and fall of leaded gasoline, which happened at different times in different countries. I'm not sure what the variance between these two types of studies is supposed to be.

But let's move on. I wrote about the study at hand a couple of years ago, and you can read my initial thoughts here. There are a few things to note:

- It's a meta-study, which means it tries to average out the results of all the primary studies on lead over the past couple of decades.

- It concludes that there's publication bias in the published studies. This is probably true, since I suspect there's publication bias in every field of study. To put it in its simplest terms, publication bias is the tendency for big, exciting results to get published while small, boring results never get written up in the first place—and if they do, they tend not to get published. This skews the public evidence in favor of positive findings.

- It includes several other results, too, some of which I have a hard time reconciling. The main one, of course, is the conclusion that the effect of lead on the crime decline of the '90s is fairly smallish.

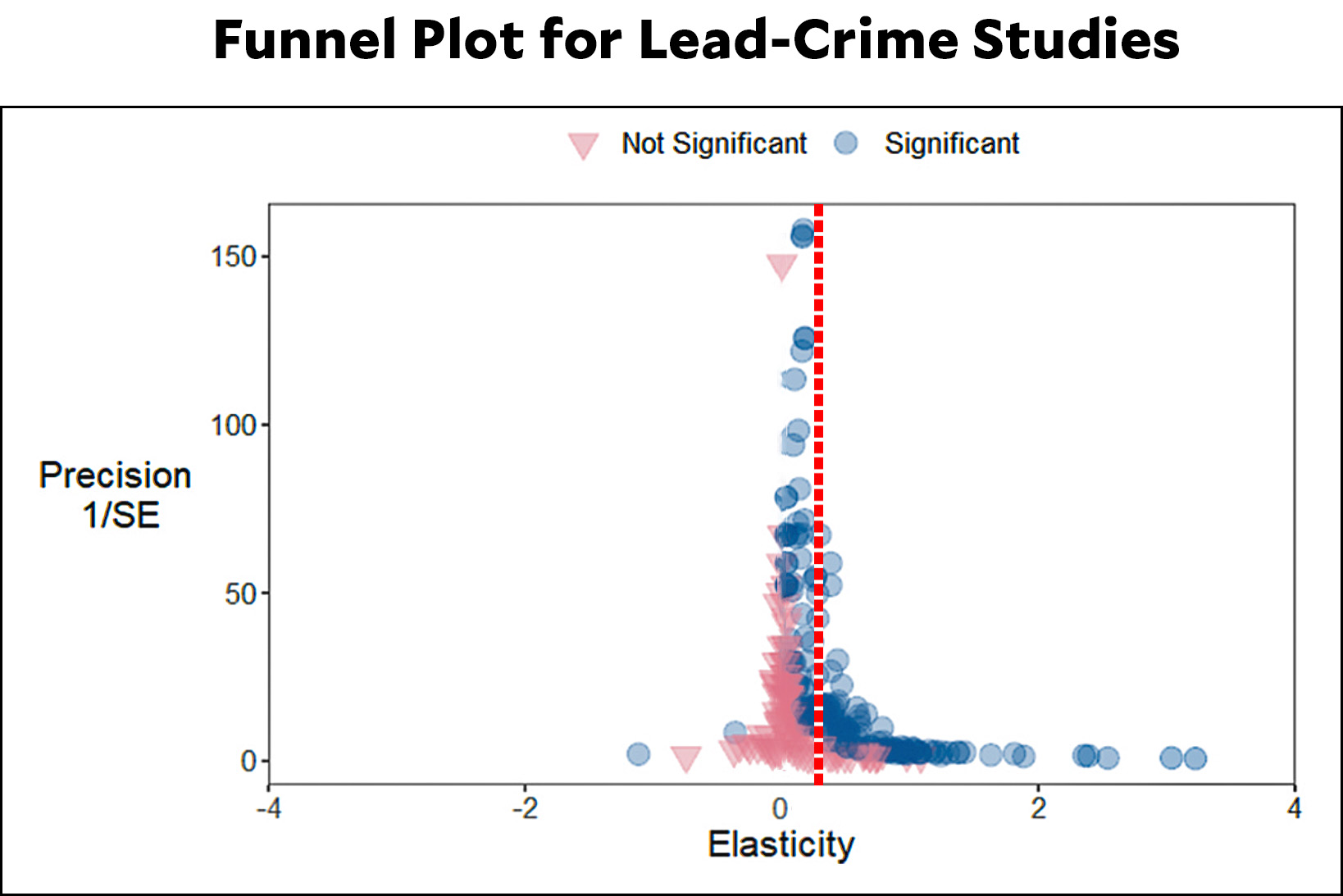

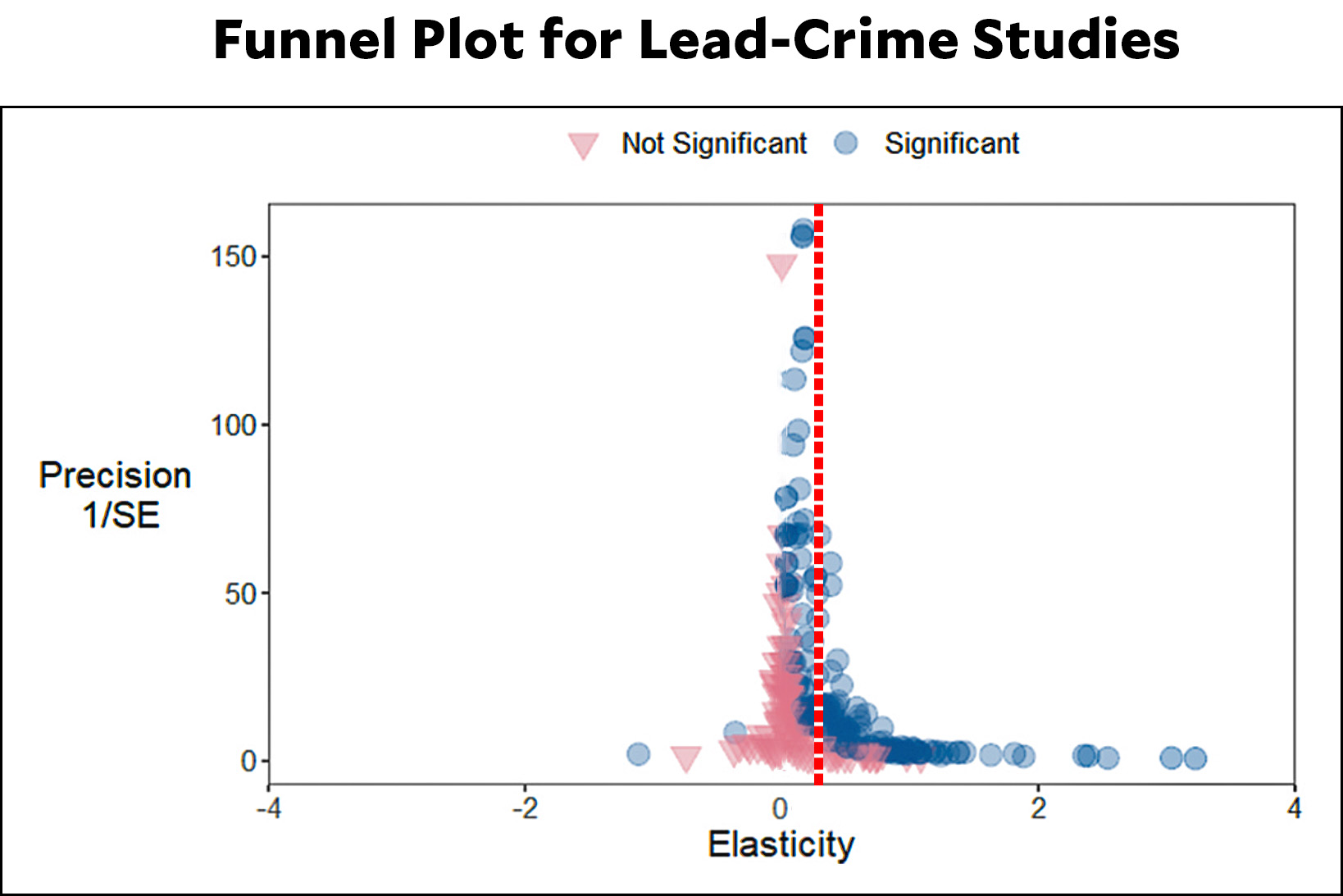

Let's start with publication bias. The authors provide two different "funnel plots" that estimate publication bias. One uses partial correlations while the other uses elasticities:

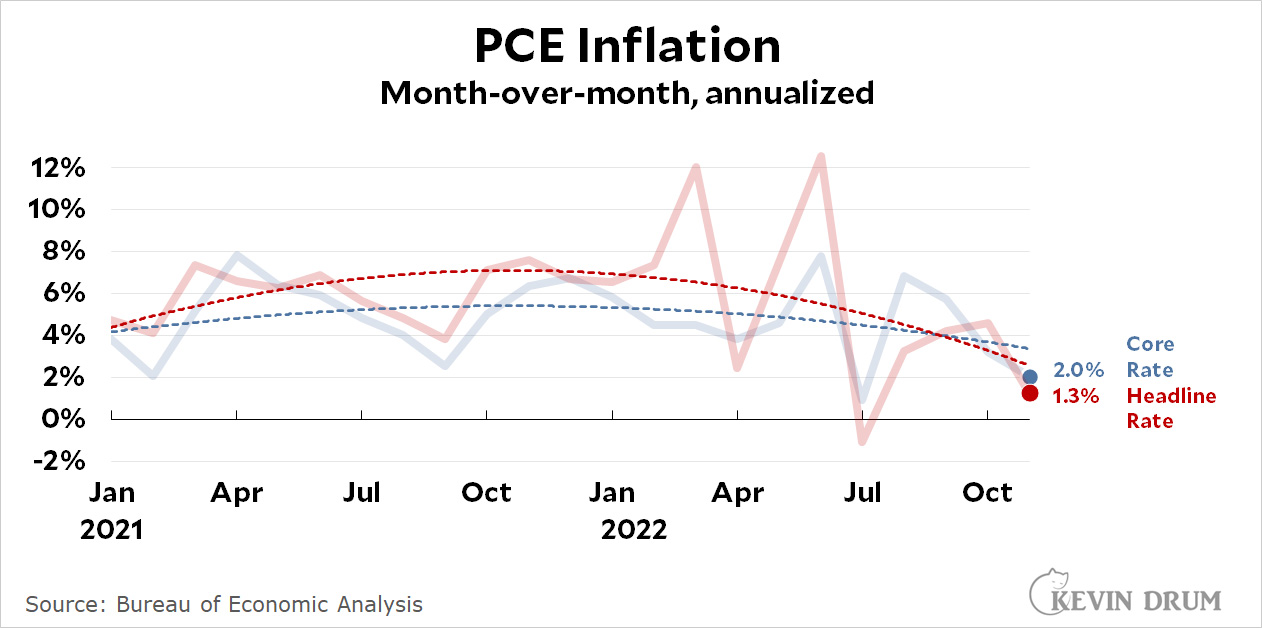

The elasticities measure the percent change in some measure of crime, given a percent change in some measure of lead pollution. They provide a better measure of the real effect rather than the measure of statistical strength the PCCs provide.

Fine. Here's the funnel plot using elasticities:

I've modified this plot to place a line roughly in the center of the data. If there were no publication bias at all the data would be symmetrical around this line. It's not. But it's also not that far off. This and other measurements suggest that publication bias is present. At the same time, this, along with other considerations, suggests the publication bias is not huge.¹

I've modified this plot to place a line roughly in the center of the data. If there were no publication bias at all the data would be symmetrical around this line. It's not. But it's also not that far off. This and other measurements suggest that publication bias is present. At the same time, this, along with other considerations, suggests the publication bias is not huge.¹

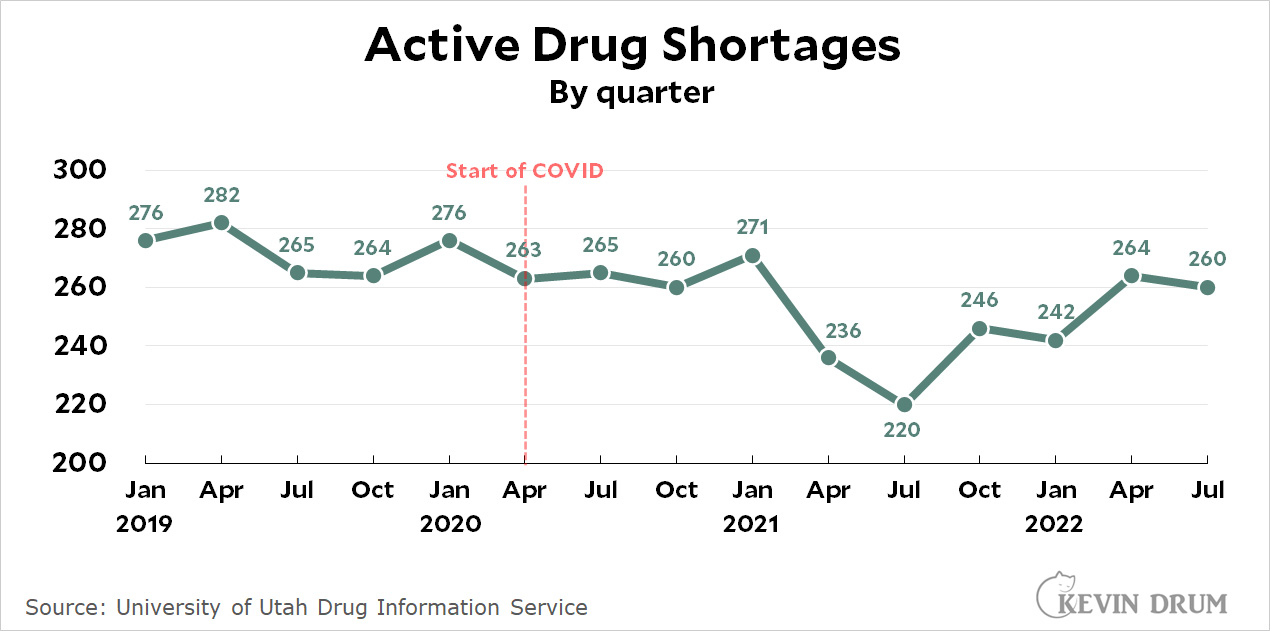

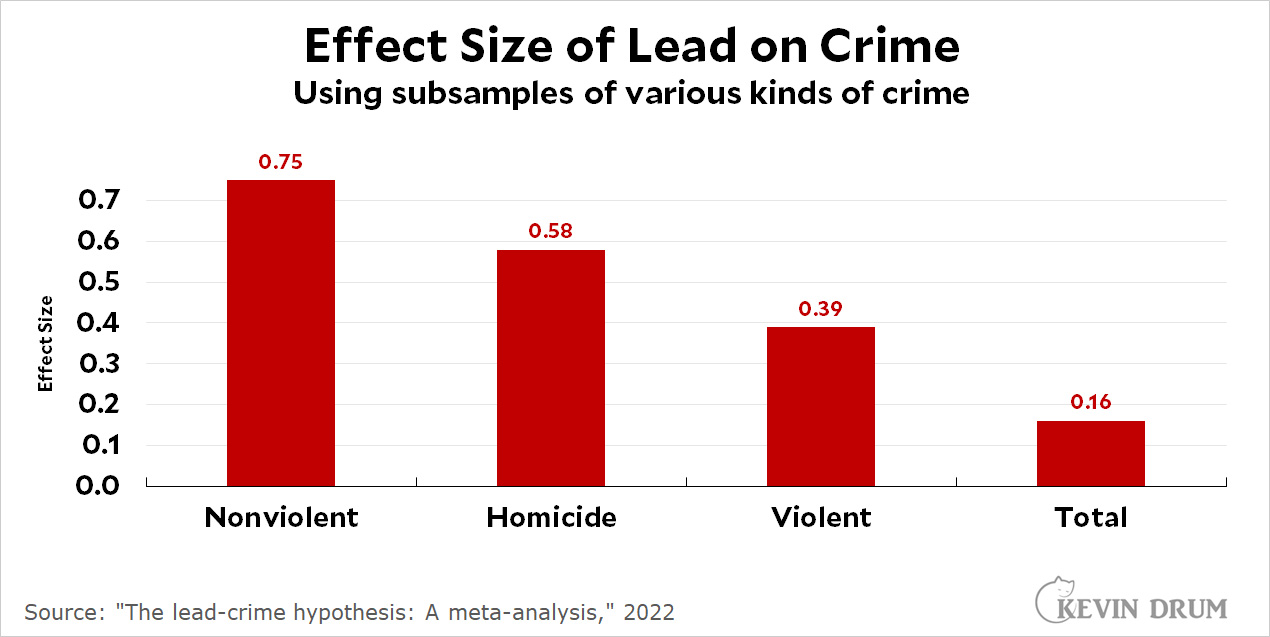

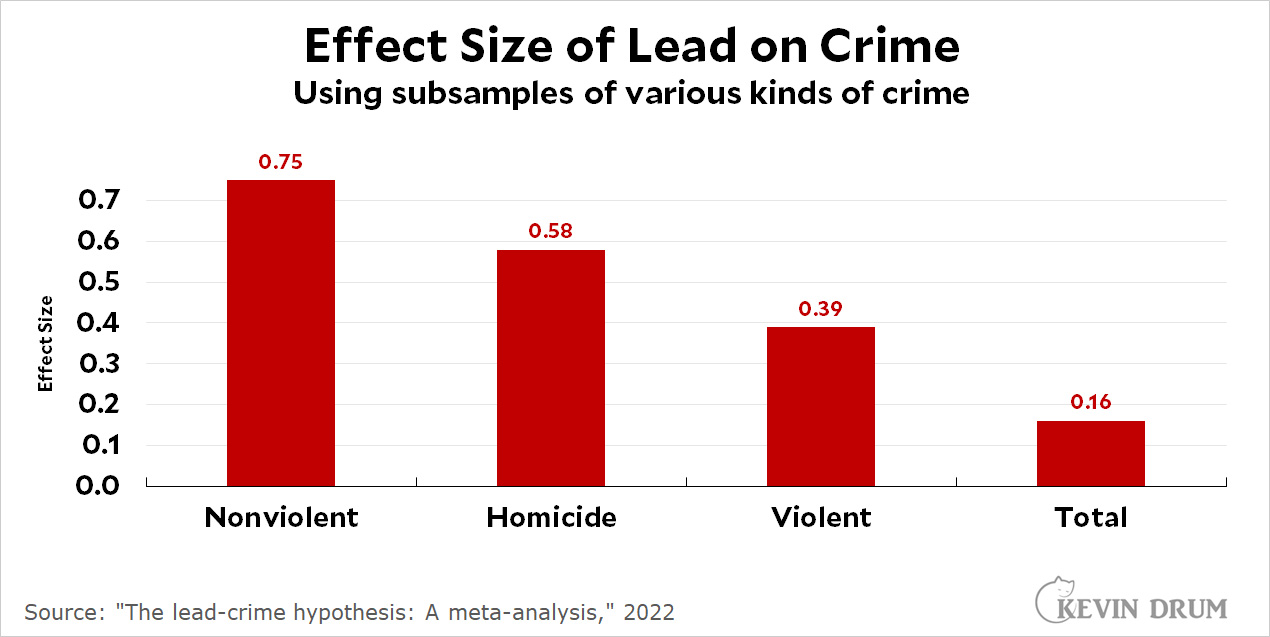

Next up is the measured effect size of lead on crime. The authors provide estimates for various subsamples, shown here:

I have a feeling I'm misinterpreting this data somehow. Everyone in the field agrees that the effect of lead is greater on violent crime than on nonviolent crime, so why are they reversed here? This makes no sense.

I have a feeling I'm misinterpreting this data somehow. Everyone in the field agrees that the effect of lead is greater on violent crime than on nonviolent crime, so why are they reversed here? This makes no sense.

I also have an objection to the authors' idea of what an "ideal" study would encompass:

The ideal specification we use is one that includes controls for race, education, income and gender, that uses individual data, directly measured lead levels, controls for endogeneity, uses panel data, is estimated without just using simple OLS or ML, uses total crime as the dependent variable....

The ideal study should focus on violent crime, not all crime. Nor should it focus very much on homicide, which many people think is the most accurate measure of violent crime.² It's not. The problem with homicide is that it has small sample sizes and produces a lot of variation, especially over small time periods. The best measure is violent crime over a long time period.

And that brings up a third point: Unless I've missed something, this paper looks only at the association of lead and crime beginning around 1990 when crime began to decline. But that's only half the data. Why do they ignore the rise of crime in '60s and '70s? That's a big piece of the evidence in favor of the lead-crime hypothesis.

And there's more! As the authors point out, most lead-crime studies are ecological. That is, they compare one area with another (different states, for example) and look to see if one thing—average lead exposure—is correlated with another thing—average crime. These studies are useful but tricky, with lots of pitfalls that can produce spurious results because they compare only averages to other averages.

The gold standard for lead-crime research is a study that compares individuals over time. One type of individual study might measure, say, bone lead levels in a random group of adults and use it to estimate childhood levels, which it then compares to present-day crime records for each person. Another type is a prospective study, where you choose a random group of kids, measure their lead exposure levels, and then look at them 20 years later to see if individual lead levels correspond to individual crime rates. The problem here is obvious: you can only do this if someone collected the childhood data 20 or 30 years ago. This didn't happen very often, and I'm aware of only a few examples:

- Cecil, University of Cincinnati Lead Study

- Sampson, Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods

- Beckley, Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study (New Zealand)

- Liu, 4 preschools in Jintan, Jiangsu province of China

- Needleman, Juvenile Court of Allegheny County

Two of these aren't even included in the meta-study, probably because they didn't fit the authors' fairly stringent requirements. However, all of them show roughly expected levels of increased crime rates in adults who were lead-poisoned as children.

TO SUMMARIZE: I'm not a statistical guru and I don't promise that I have everything right here. Nor should this post be construed as any kind of criticism of the authors. Meta-studies are good things; publication bias is real; and their methodology seems reasonable.

That said, a few things seem a little out of whack. It would be nice if the lead-crime community could take a look and formulate a response of some kind.

¹As I've written before, it's useful to consider how likely publication bias is in any particular area. Are you looking at studies of antidepressants? Pharma companies would love to bury null results, so watch out for publication bias! Are you looking at quick-and-dirty studies that use classrooms of undergrads as their subjects? Those often aren't even worth writing up if the results are uninteresting, so watch out for publication bias!

Lead-crime studies, by contrast, are moderately complicated and take a while to finish. That's a chunk of your career, and you probably don't want to throw one out just because it wasn't super exciting. There are also no big motivations to ignore studies that are inconvenient. Bottom line: this is not a field that seems likely to produce a huge amount of publication bias.

²Homicide has the advantage of being easy to estimate: someone is either dead or they aren't. Other types of violent crime require a certain amount of human judgment to categorize them properly.