Ezra Klein's podcast with Larry Summers wasn't just about inflation. Ezra also asked Summers to name three books that had influenced him:

Third, a book that will come out in the next several months, Brad DeLong’s “Slouching Towards Utopia,” which is, I think, a really remarkable and powerful placing of all of economic history in perspective, that gives a sense that at some level I had known but never appreciated of how profoundly different the 20th century was than all other centuries and points towards the combined power of science and markets to change the world profoundly, and sometimes, in some ways,  for good, and sometimes, in some ways, for ill. I think anybody who wants to propound about economic policy should read that book.

for good, and sometimes, in some ways, for ill. I think anybody who wants to propound about economic policy should read that book.

Now I want to read Brad's book too! I remember giving some remarks a few years ago that touched on the most important events and developments of past and future centuries. I opined that the 19th century was the century of technology: steam engines, germ theory, evolution, electricity, and continent-spanning railroads. The 20th century was the century of market economics: Kuznets and Keynes, active central banking and the end of gold, the decline of tariffs, frictionless international banking, and flows of capital around the globe that would make the old doges weep. Now we're in the 21st century, which will be the century of artificial intelligence.

So yes, we are living today in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution and the Economic Revolution, which makes the world profoundly different from any previous era. And now, having barely mastered basic science and economics, we're barreling toward the Digital Revolution with hardly a thought about how that will change the world just as profoundly. Mass unemployment will prompt revolts that make the Luddites look like monks and will likely kill off liberal democracy. With luck, we'll avoid being too stupid and greedy about this transition and both liberal democracy and market economics 1.0 will be replaced with something better and far more rewarding for future generations. But there are no guarantees. It's usually not a good idea to bet against greed and stupidity whenever the overclocked apes h. sapiens are involved.

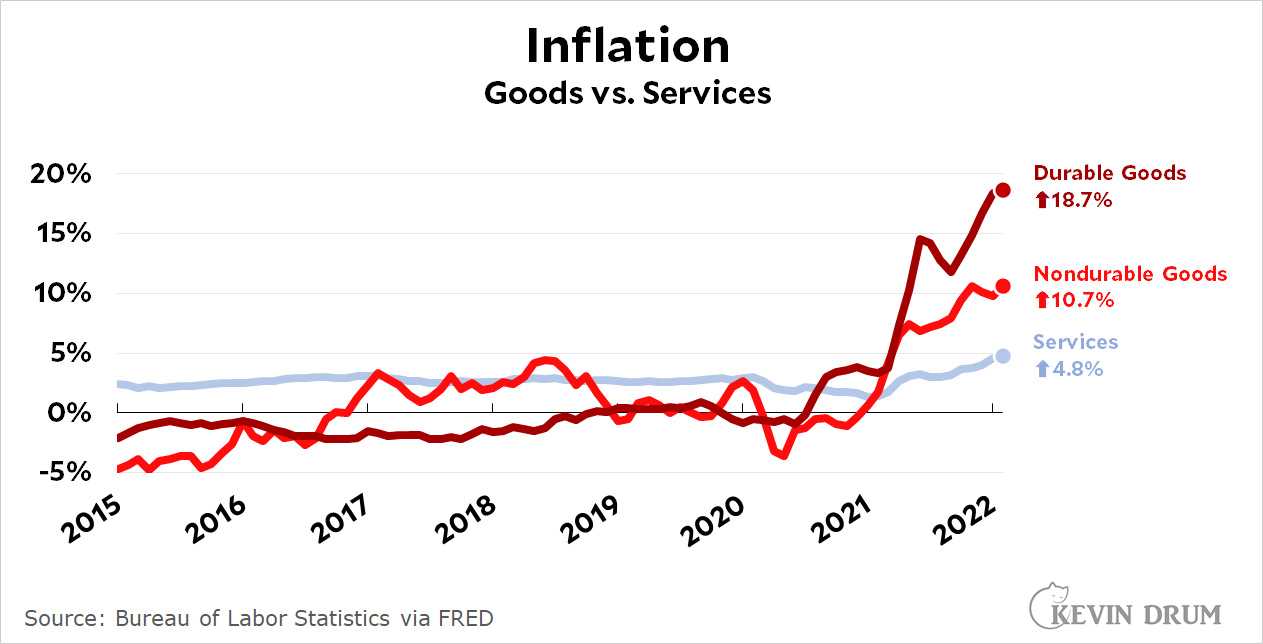

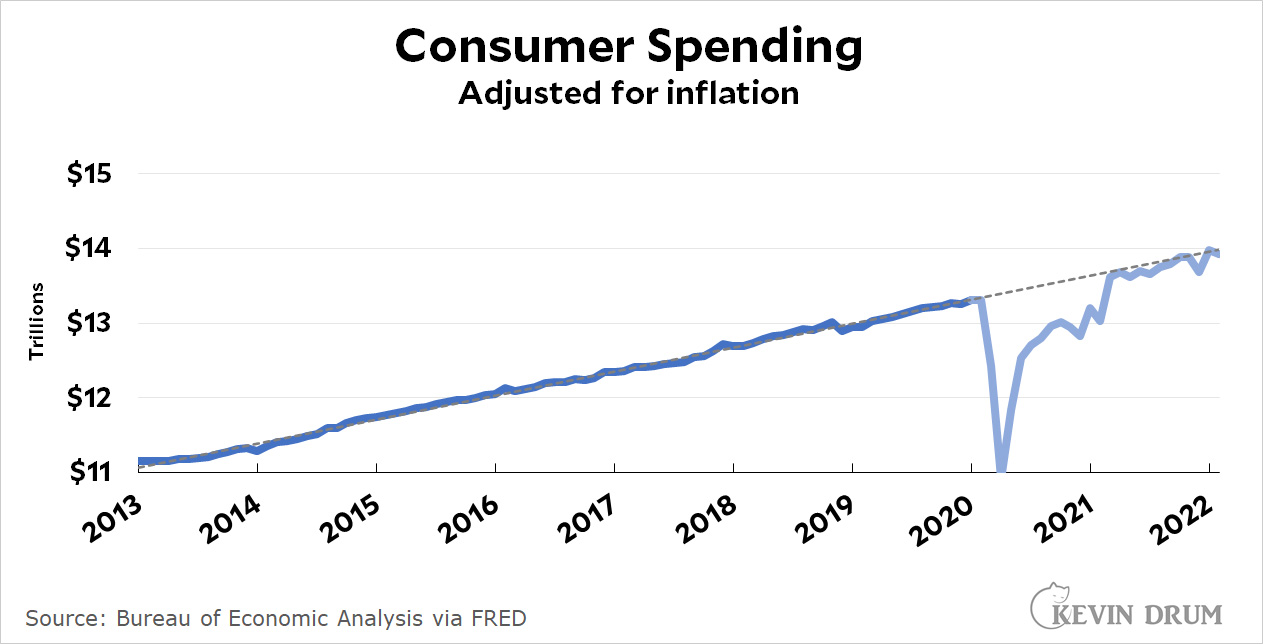

Consumer spending was down slightly in February, which keeps it right on the pre-pandemic trendline. It's yet another indication that consumer demand isn't spiraling ever upward. On the contrary, it remains well anchored.

Consumer spending was down slightly in February, which keeps it right on the pre-pandemic trendline. It's yet another indication that consumer demand isn't spiraling ever upward. On the contrary, it remains well anchored.