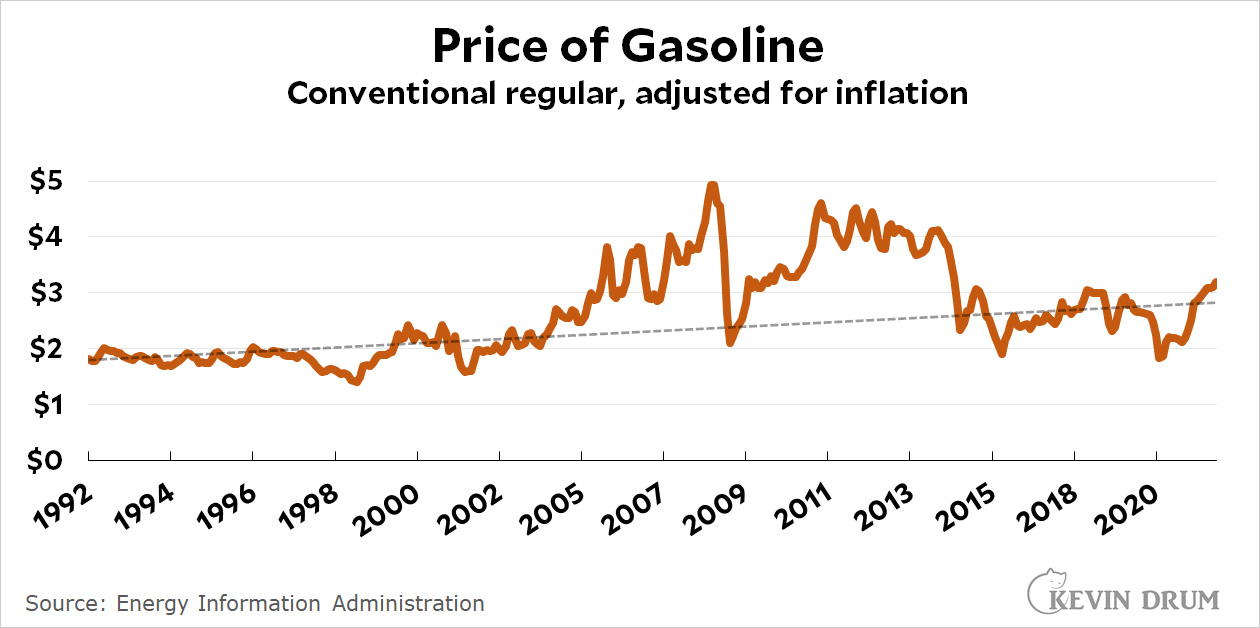

I don't know why, but every once in a while I like to remind myself of what the price of gasoline looks like over the long term. Here it is:

Month: November 2021

On Instagram, it’s scammers vs. scammers

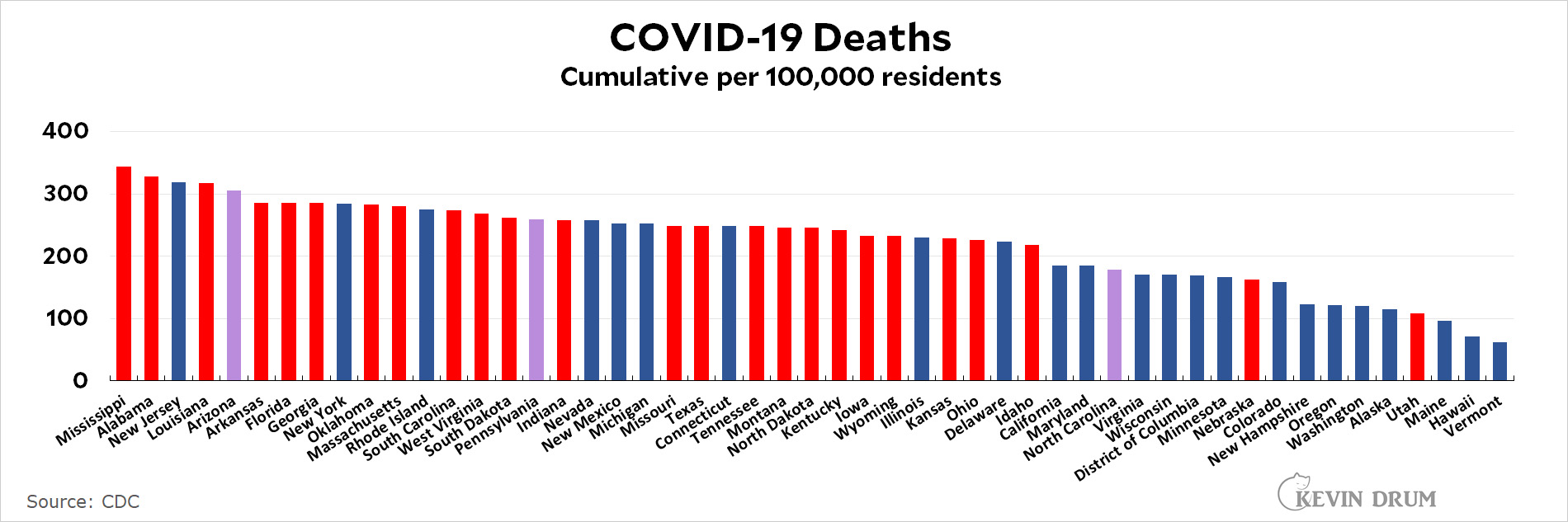

Cumulative US COVID-19 deaths by state

Lunchtime Photo

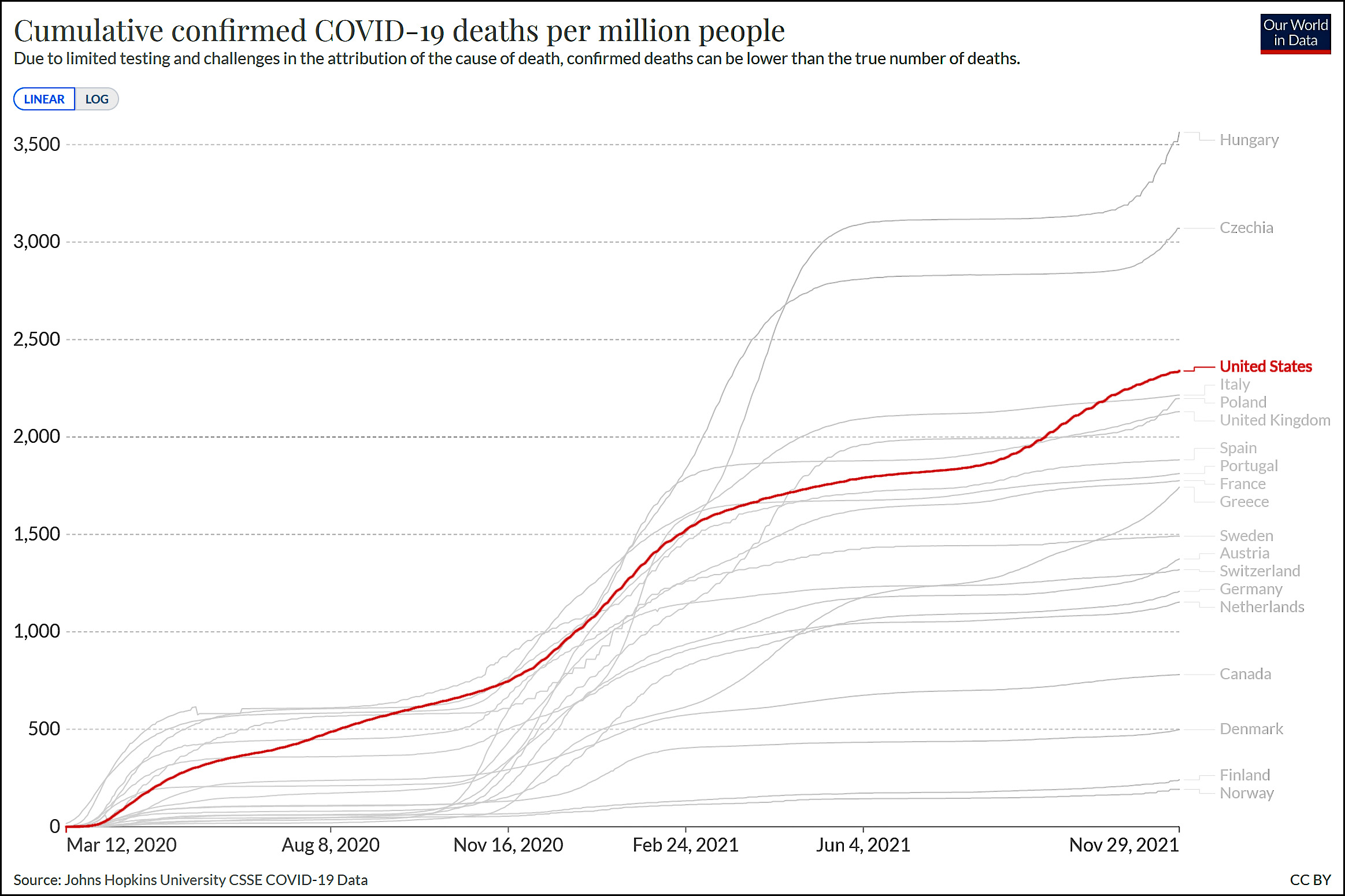

Cumulative COVID-19 Deaths in the US and Europe

I've slowly moved away from showing the 7-day rolling average of COVID-19 deaths as it's become clearer that such comparisons are useless since different regions experience waves at slightly different times. If you cherry pick the right week, it looks like the US is doing great and Florida is a world leader in fighting COVID-19. Pick another week and they look like pandemic central.

Now that COVID-19 has been around for nearly two years, the better thing to look at is cumulative cases and deaths. This does a superior job of showing how different countries have responded to COVID-19 over time. Here it is for the US and Europe:

The United States continues to be worse than nearly all our peer countries in Europe. The two big exceptions are Hungary and Czechia, which act as cautionary tales. Hungary began a huge upsurge last November and eventually acted on it. But it was too late. Lackadaisical policies allowed infections to get out of control, and new mask mandates were both late and not enough.

The United States continues to be worse than nearly all our peer countries in Europe. The two big exceptions are Hungary and Czechia, which act as cautionary tales. Hungary began a huge upsurge last November and eventually acted on it. But it was too late. Lackadaisical policies allowed infections to get out of control, and new mask mandates were both late and not enough.

Czechia is even more heartbreaking. They had great policies and were the envy of Europe for over a year. But then they declared victory too early, and with an election coming up last October the government didn't want to reinstate unpopular countermeasures. The result was catastrophic.

The United States, needless to say, has never adopted suitable policies and has paid a bigger and bigger price for that. We haven't always been quite the worst performer among our peers, but we are now with the exception of the two outliers.

But we just don't care enough.

How can we make more people fear Republican rule?

Greg Sargent says we need to do a better job of demonizing Republicans:

With President Biden’s approval rating tanking, we’re getting constant reports about the handwringing internal debate among Democrats over how to turn things around for the midterms. Yet something is largely missing from this discussion: a serious effort to ask whether Democrats might go much further than they currently are in prosecuting an effective public case against ongoing GOP radicalization.

In one sense, Greg is missing something here: Democrats already have a long history of demonizing Republicans, just not in quite the way he's imagining. Just ask any Republican who's been the target of ads about cuts to Medicare:

That one is famous for going a wee bit too far, but it's generally the case that Democrats demonize Republicans for supporting cuts to social welfare programs. And it works: the public is pretty much convinced that Republicans hate poor people.

Now, in this case Greg is thinking about things like mask hysteria and CRT nonsense. But the question is whether topics like this are salient to the voters who matter: those who are likely to change their minds. They certainly aren't salient to either Republicans or Democrats, who already have strong opinions about these things. But there's some good news! Independents support mask mandates and are therefore potential targets of Democratic efforts to demonize Republicans for putting us all at risk. The problem is that I suspect this is a very low-salience topic. Very few Independents are going to base their vote on opposition to mask mandates no matter how hard Democrats try.

And the news on CRT is even worse. Nobody may know what CRT really is, but Indies oppose teaching it. You can't successfully demonize Republicans for this if most people are on their side in the first place. In swing districts, even plenty of Democrats oppose teaching CRT in public schools.

For reasons that we could discuss at length, it's really hard to demonize Republicans. For years they've represented wildly irresponsible views, the worst of which at the moment is the conviction that Democrats stole the 2020 election and that justifies passing new laws that give Republicans more power to count votes. That's about as bad as it gets, and even so most non-Democrats don't consider it a big deal.

So the right question to ask is: If even something this alarming produces little more than a yawn outside the ranks of Democrats, what the hell would it take to make people genuinely afraid of Republicans?

This is a question I've been pondering for years and I still come up blank. The simplest answer, I think, is that Republicans are generally conservative in the literal sense: they want things to stay the same, and extremism in the defense of doing nothing just doesn't bother most people. Conversely, it's easy to demonize Democrats: liberals want to change things, and extreme changes are scary as hell. So liberals are working under a handicap from the start.

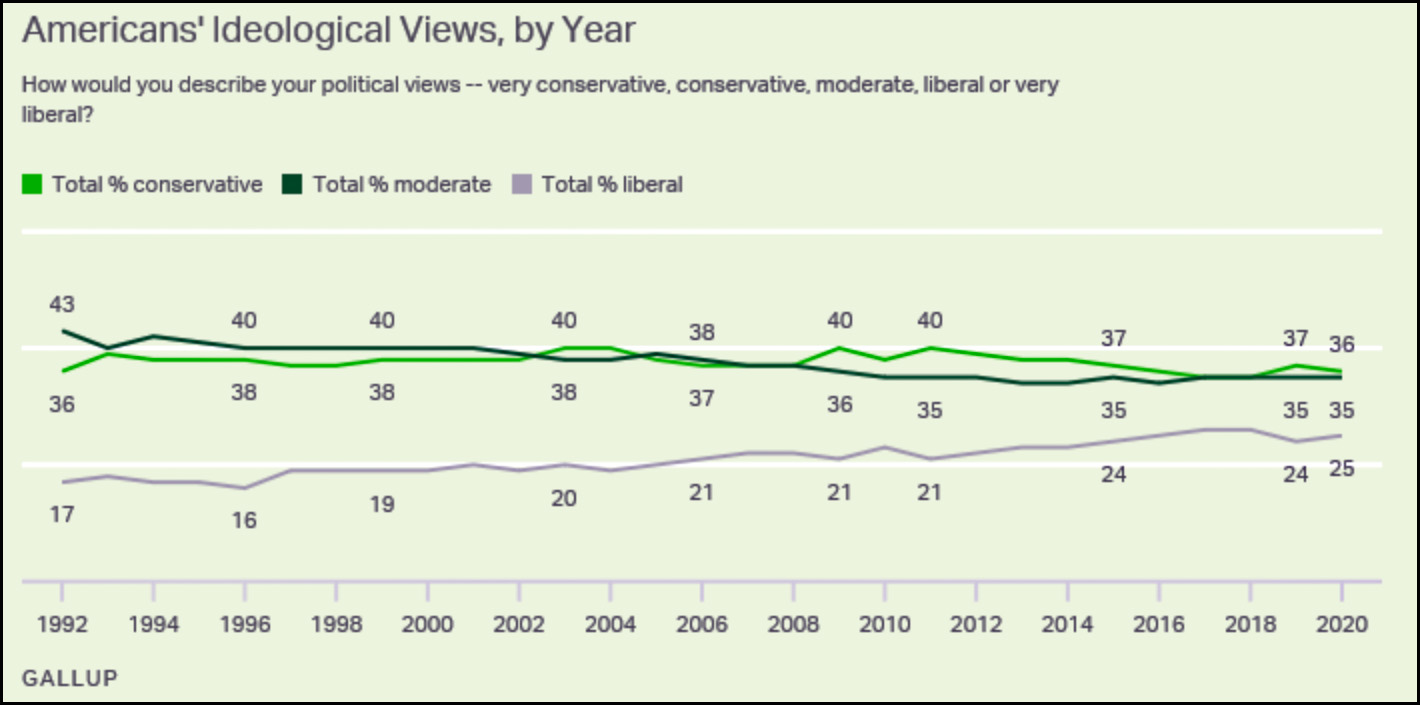

As you can see, Democrats have been successful at making liberalism more popular over the years, but they've been distinctly unsuccessful at making people hate conservatism: self-IDed conservatives amounted to 36% of the population in 1992 and amount to . . . 36% of the population today.

As you can see, Democrats have been successful at making liberalism more popular over the years, but they've been distinctly unsuccessful at making people hate conservatism: self-IDed conservatives amounted to 36% of the population in 1992 and amount to . . . 36% of the population today.

I'm completely in agreement with Greg that we should try to make more people fear Republicans. I'm just not sure how.

Twitter bans pictures of your mother

This is genuinely fascinating:

Twitter Inc. said users will no longer be able to share private media, such as photos and videos, of another person without their permission, a move aimed at improving privacy and security.

This doesn't mean you can't post a picture of your lunchtime buddies, but it does mean that if one of your buddies complains then the picture will be taken down.

In one sense, this strikes me as going way too far. There's a sense among some people already that it's generally illegal to post a picture of a private citizen without permission. This is entirely untrue, especially of pictures taken in public places. Twitter's action is going to convince ever more people that they have a right to privacy in their public actions.

On the other hand, Twitter is such a transitory medium that it hardly matters. At a minimum it will take days or weeks for a person to discover that their picture has been posted to Twitter and to then get Twitter to remove it. By that time, who cares? Most tweets get attention for about 15 minutes and then rapidly deposit themselves in the ash heap of history. The ones that stay relevant longer tend to involve celebrities or politicians and are exempt from the policy.

More than likely, the only significant result of this will be a big increase in Twitter's policing team. No wonder their stock went down on the news. And no wonder that Jack Dorsey stepped down as CEO yesterday.

A few notes on Peter Jackson’s “Get Back”

Last night I watched Part 1 of Get Back, Peter Jackson's epic Beatles documentary put together from 60 hours of film that was shot while the band was creating and rehearsing a set of songs for a live BBC special in 1969. Regardless of anything else, it's fascinating in a historical sense for anyone who even likes the Beatles, let alone reveres them.

But aside from that, how good was it? I'm a big Beatles fan, and I've read quite a bit about them, but raw documentary footage is almost always a bit of a slog and this was no exception. Honestly, if it were about any other band I don't think I would have made it to the end.

Going into it, I was under the impression that it put paid to the notion that the Beatles were at each others' throats by 1969. But it didn't really. They had agreed to do the TV special, of course, but beyond that it was pretty obvious that no one was having much fun. Here are some random observations.

- To say that Paul McCartney was the engine of the band at this point is to massively underrate him. As near as I could tell, he was almost literally the only one actively interested in making music during these sessions.

- Except for George Harrison, that is, who tried to bring in a few songs he'd written at home. These got a tepid response, eventually leading to his famous 12-day "resignation" from the band. (McCartney eventually decided that Harrison's songwriting had improved enormously, but it was too little too late.)

- John Lennon spent the sessions apparently stoned and completely disengaged. He smiled amiably and played his parts, but that was about it.

- Ringo Starr was Ringo Starr. He mostly just hung around while the others figured out the music. This is the fate of many drummers.

- The whole thing was remarkably haphazard. They were rehearsing in a huge, bare film studio just because someone offered it to them. They wanted certain kinds of equipment and had a hard time getting it. The acoustics were terrible. These were the Beatles! Nobody could be bothered to set up a nice rehearsal space for the greatest rock band of all time?

- At one point McCartney says he's been acting as sort of the leader of the band and doesn't feel comfortable with it. This may or may not have been disingenuous on his part, but the only one to even respond was Harrison.

- All this said, except for Harrison storming out at the end of Part 1, there was no real animosity on display. Just a bunch of guys trying to put together a bunch of new music on an insane timetable and seeming a little dispirited about it. And yet, they'll do it!

- The only times when the foursome seem to be really enjoying themselves is when they're jamming on old classics written by someone else. When the pressure of creating music is off, they still get a kick out of playing with each other.

- It's surprising not just how unprepared they are, but that over the course of a decade they still haven't settled on how to do recording sessions. These habits usually emerge over time and then become stable just through inertia. In this case, if you didn't know who these guys were, you might guess that it was the first time they had ever made a record together. I imagine this was partly because there was no firm leader of the band that everyone looked up to.

- One of the problems with Part 1 is that it shows the period when the songs are just barely taking shape. This is historically interesting but musically a bit tedious. I'm genuinely curious to see how Parts 2 and 3 shape up, when the lads are trying to resolve their personality conflicts and are playing their songs in more recognizable form. I will watch them shortly.

For years, people have been arguing about why the Beatles broke up. There are loads of standard theories:

- The death of manager Brian Epstein in 1967 left the band with no one they respected who could rein them in.

- Yoko Ono. Nuff said.

- Growing disagreement between John and Paul about the kinds of songs they wanted to play.

- After a decade, they just generally got tired of each other.

- John's heroin addiction starting in 1968 made him unreliable and prone to temper tantrums.

- The band went through a serious business disagreement during 1969, which led to John, George, and Ringo hiring Allen Klein as the Beatles' business manager. This was done against the vehement wishes of Paul.

- Rather famously, everybody else got tired of Paul's perfectionism, which led to endless takes and grueling recording sessions.

- Toward the end, George wanted more of his songs on Beatles records than the usual two he was allotted by John and Paul. He didn't get what he wanted, which pissed him off considerably.

But why pick one? They were all true, and were more than enough reason for any group to call it quits. And it worked out: the Beatles are the quintessential 60s band, and it seems only right that when the 60s ended, so did they.

Here’s a closer look at the Great Resignation

Over at The American Prospect, David Dayen has a good piece about the "Great Resignation," which he attributes mostly to the fact that low-wage jobs have become intolerable:

Work at the low end of the wage scale has become ghastly over the past several decades....“The U.S. needs a reset, needs a big push, to get to a place where work is more secure and livable for a lot of the population,” said MIT economist David Autor, who has tracked the misery of American deindustrialization and the shock of China’s rise as a manufacturing powerhouse.

....Quit rates and job-to-job transitions in the Great Resignation are mostly taking place among workers with less than a high school education, whose daily toil is typically spent in dead-end low-wage jobs, an engine for corporate profits that produces some of the grimmer existences in the industrialized world.

The particulars of low-wage work have been well documented for years: stagnant wages, short staffs, poor conditions, erratic schedules, no benefits, overbearing managers, and the constant fear of losing your job.

I'm never quite sure what to think of this. I agree that low-wage work in the US is pretty appalling, and it seems to be getting worse in some ways. Reports of workers increasingly being bound to computer-generated daily schedules instead of schedules worked out in advance are especially hair raising. How can you raise a family with a work schedule that you literally don't know until 24 hours in advance?

On the other hand, there's this:

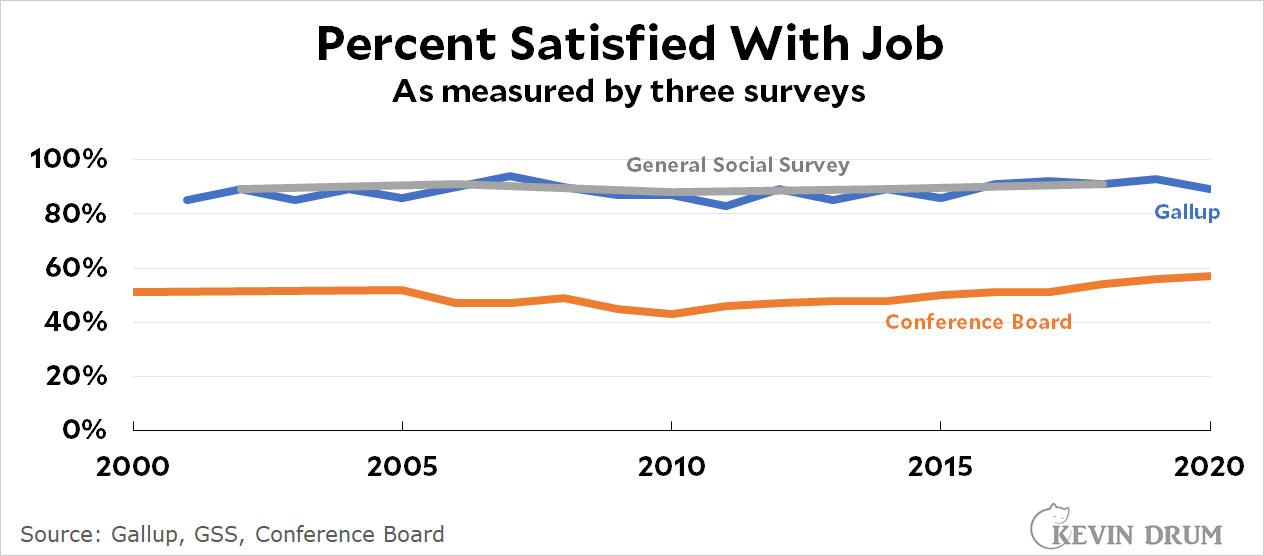

Field surveys are basically unanimous: worker satisfaction with their jobs has changed only slightly over the past 20 years, and not for the worse. The vast majority of workers are perfectly happy with their jobs, and this was true all the way through 2020.

Field surveys are basically unanimous: worker satisfaction with their jobs has changed only slightly over the past 20 years, and not for the worse. The vast majority of workers are perfectly happy with their jobs, and this was true all the way through 2020.

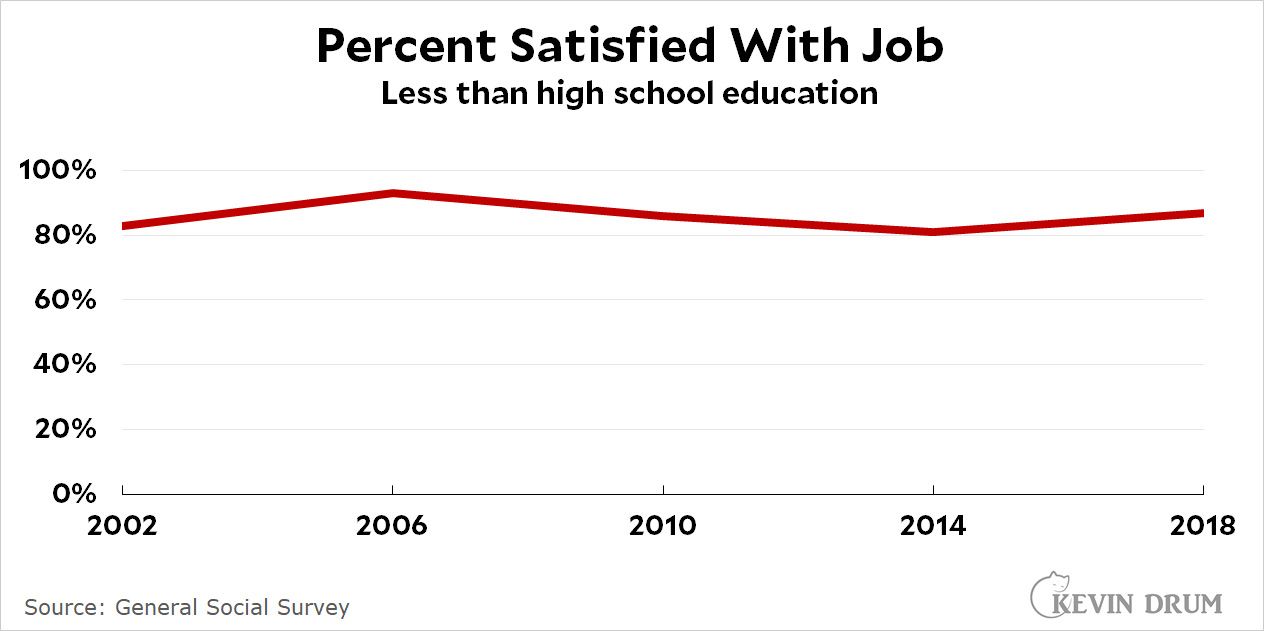

Two of these surveys don't break out results by educational level, but the GSS does. Here's what it says about workers with less than a high school education:

Again, there's not much change at all. In 2002 GSS reports that 83% of low-education workers were satisfied with their jobs. In 2018 it was 87%.

Again, there's not much change at all. In 2002 GSS reports that 83% of low-education workers were satisfied with their jobs. In 2018 it was 87%.

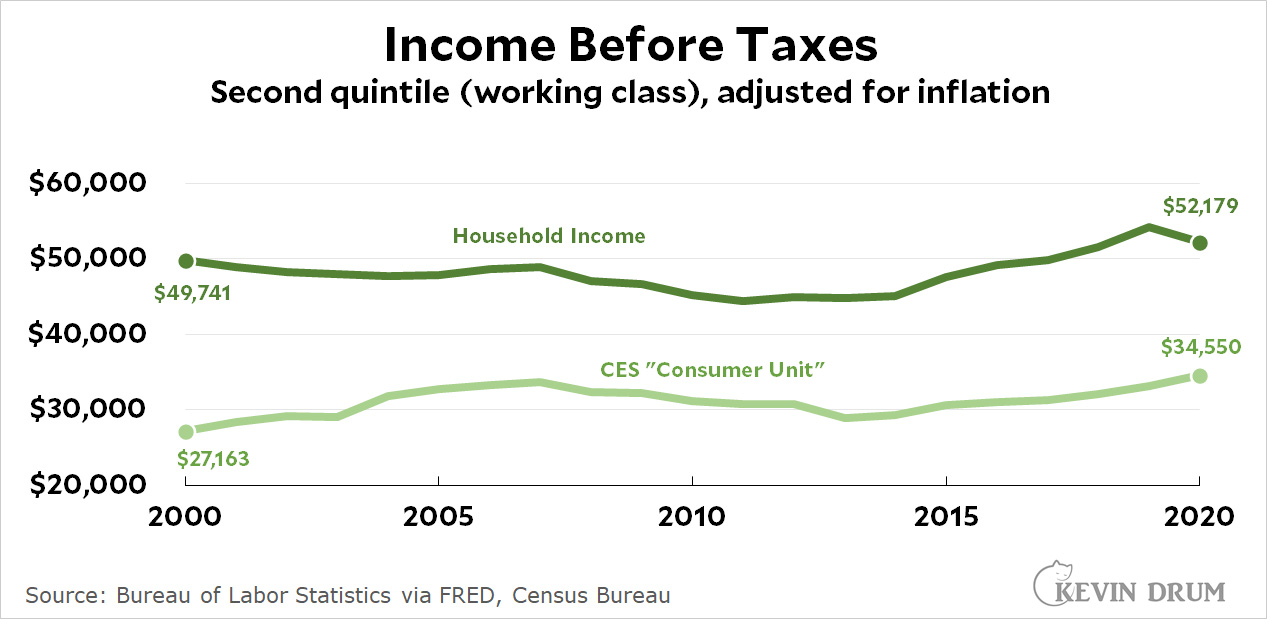

Here is earnings data for the second quintile of American workers. These are generally blue-collar workers who earn lowish middle-class wages:

These are not princely sums. Nevertheless, they've been rising since 2014 and were higher right before the pandemic than they were two decades ago.

These are not princely sums. Nevertheless, they've been rising since 2014 and were higher right before the pandemic than they were two decades ago.

(The very lowest income quintile was dead flat from 2000 through 2020.)

So I dunno. Prior to the pandemic there was no real evidence that workers were especially unhappy. Just the opposite, in fact. So what's really going on? Are surveys unreliable indicators? In retrospect, have low-income workers decided they were less happy than they thought at the time? Are they sick and tired of pandemic working conditions and eager to switch jobs just for a change of scenery? Is it nothing more than a year's worth of normal job restlessness all squashed into a few months? Or what?

Lunchtime Photo

This is a drone's eye view of a tanker docked at the Port of Long Beach. The drone was about 300 feet above the ship.

UPDATE: Photography? Phhht. The comments are all about whether it's legal to fly a drone over a port. Here are a few things about that.

- A rule was finalized in April that makes all airspace, by default, legal for flying small drones. The point of the law was to enable package delivery, but it applies to all drones.

- The FAA is in charge of airspace, and they generally care about airports and not much else.

- That said, maps built into the drone software outline all restricted airspace. In fact, the drone software won't even fly into restricted airspace. I was surprised the Port of Long Beach was unrestricted, but as long as you stay out of the flight paths of local airports it's OK.

- Owners of private property can forbid you from taking off or landing on their property. I was on public land when I launched the drone for this picture.

- If someone ever asked me to stop flying my drone, I'd stop. No one ever has.