Exciting news today: the Fed has released its report on the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. You're already salivating, aren't you?

I've read through it, but I want to say up front that it presents me with a problem. I've taken a very public stance that SVB didn't really do anything seriously wrong, and this means I need to be doubly careful about how I interpret the Fed's report. I don't want to cherry pick just the bits that support my view, but neither do I want to bend over backward in the other direction out of a misguided sense of fairness. And the Fed report makes this balancing act especially hard because it says a lot of different things. If you have a point you want to make, you can find it somewhere.

So I'm going to do my best, but just beware that anybody with an axe to grind can find excerpts in this report to support their view, whatever it happens to be.

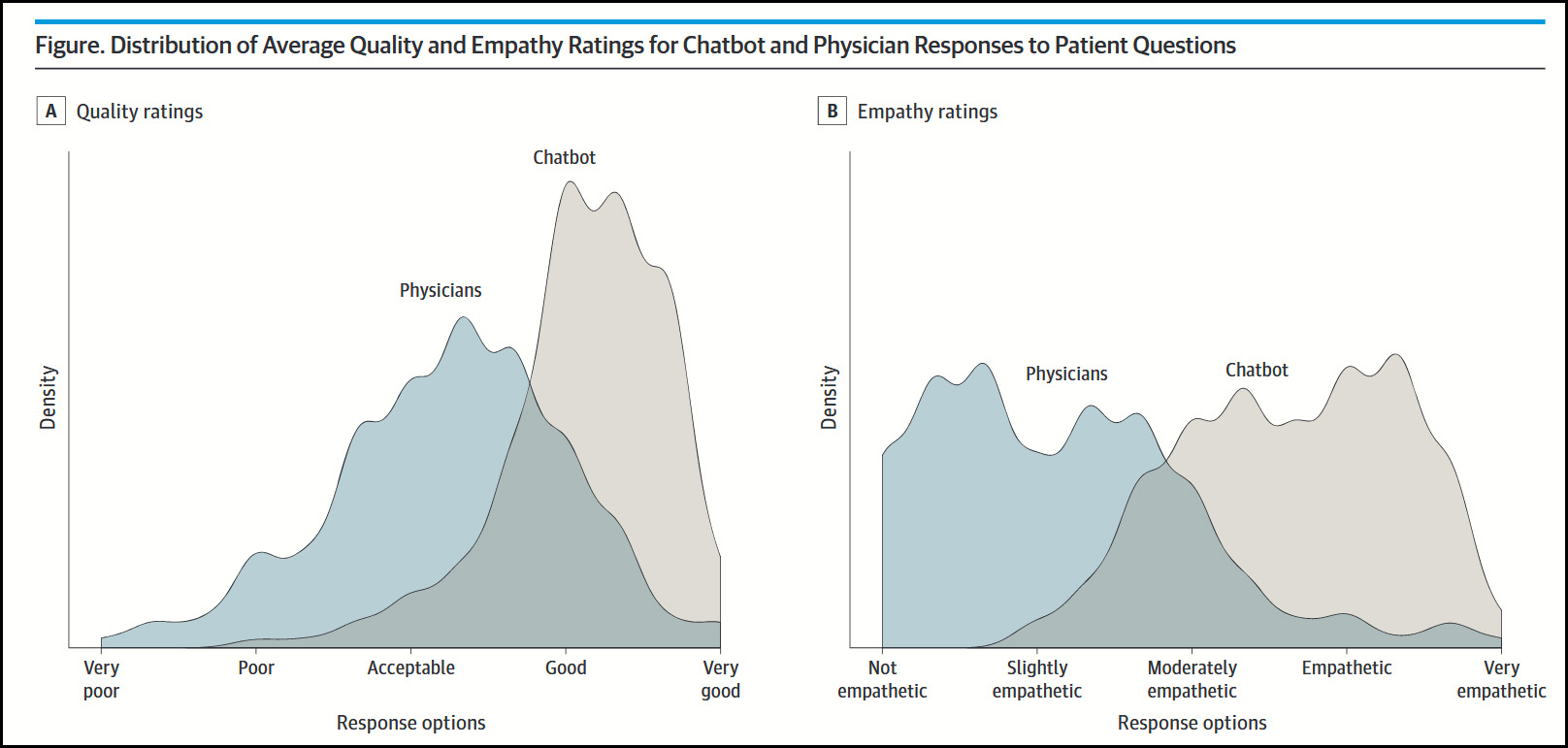

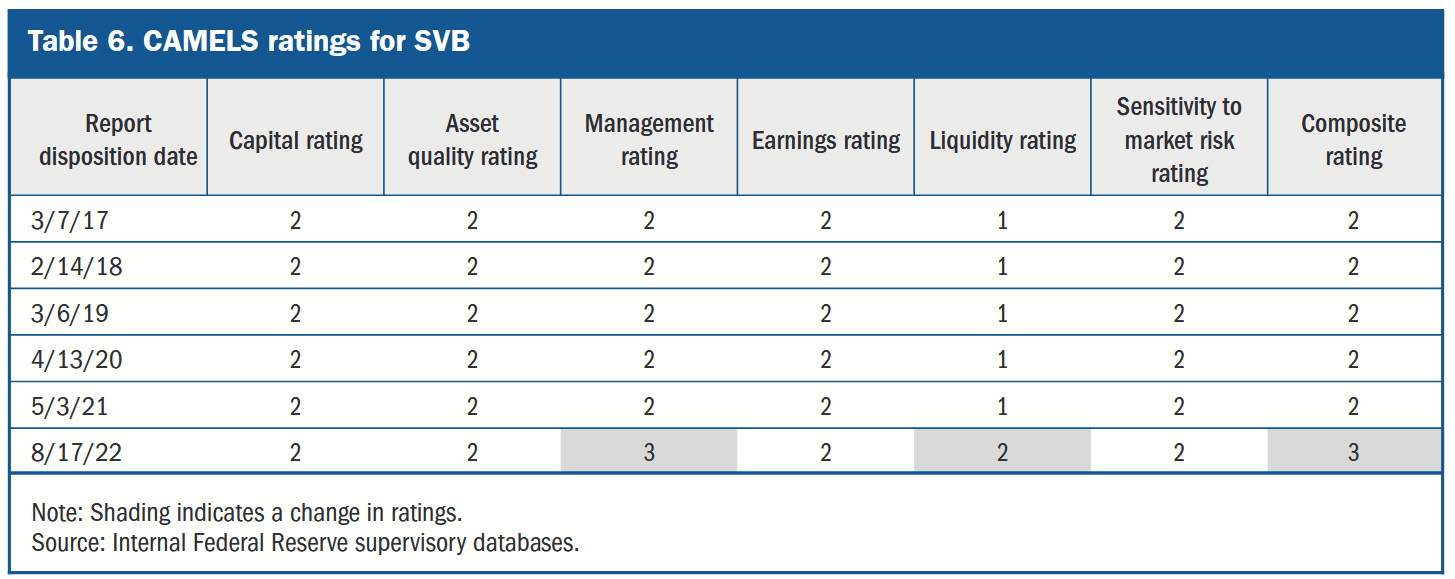

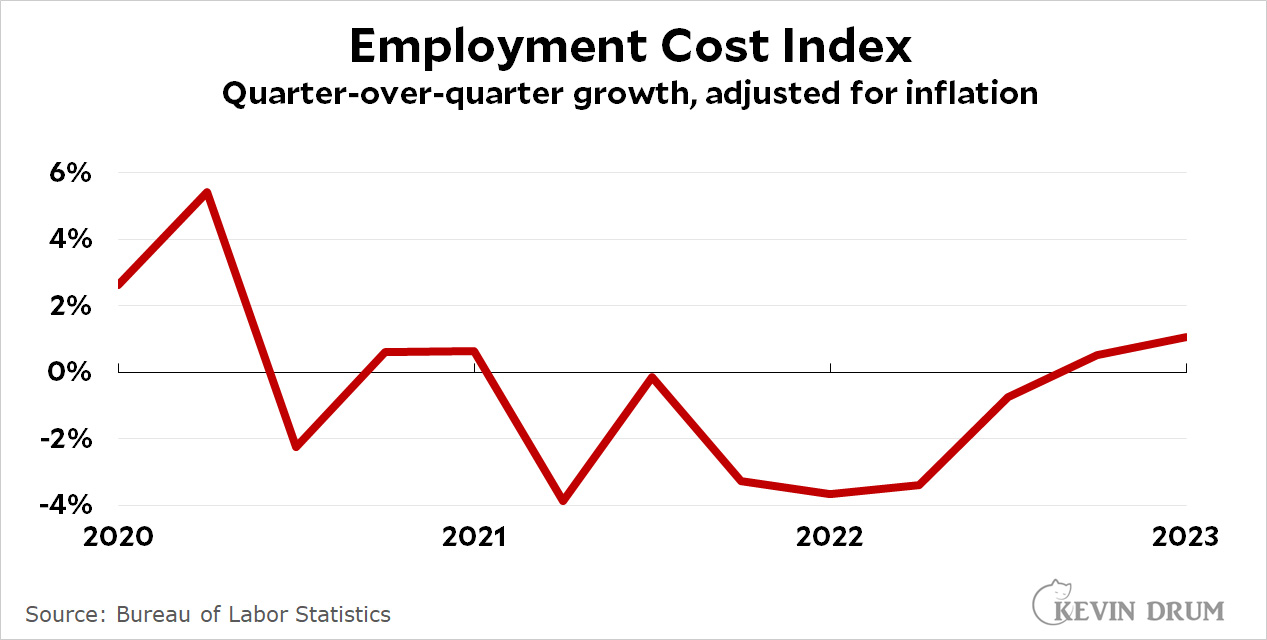

Let's start off with a chart:

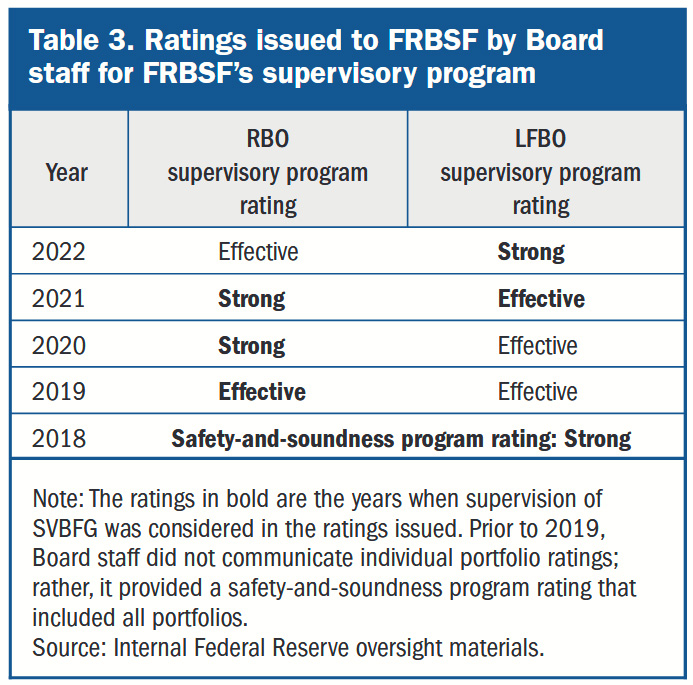

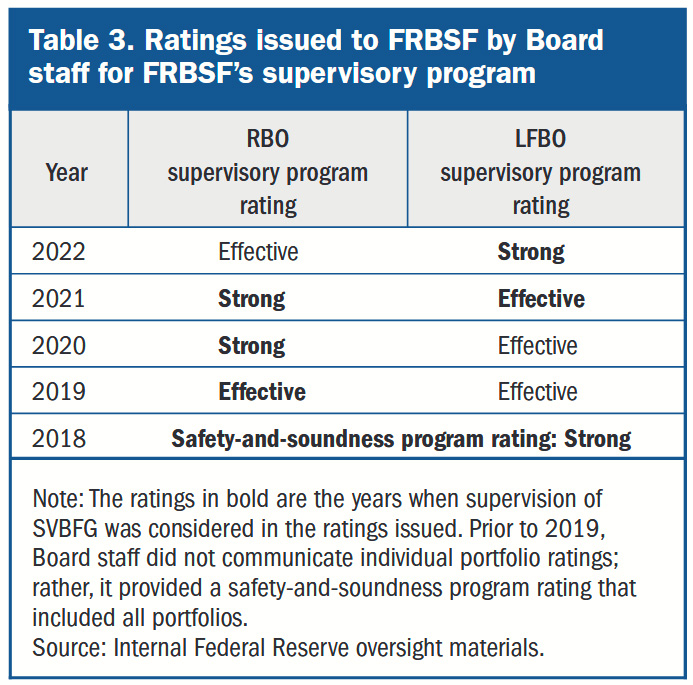

This shows SVB's ratings from 2017 through late 2022. During this entire time both its capital and liquidity ratings were either excellent or good. In early 2021 supervisors wrote a warning about SVB's liquidity management and stress testing (though not about its actual liquidity position) but there was nothing after that. Here are the Fed's ratings of SVB's supervision programs:

This shows SVB's ratings from 2017 through late 2022. During this entire time both its capital and liquidity ratings were either excellent or good. In early 2021 supervisors wrote a warning about SVB's liquidity management and stress testing (though not about its actual liquidity position) but there was nothing after that. Here are the Fed's ratings of SVB's supervision programs:

In 2021, because of SVB's rapid growth, supervision switched from RBO (regional banks) to LFBO (large banks). However, the bank's supervision rating, even under the LFBO rules, improved in 2022 from Effective to Strong.¹

In 2021, because of SVB's rapid growth, supervision switched from RBO (regional banks) to LFBO (large banks). However, the bank's supervision rating, even under the LFBO rules, improved in 2022 from Effective to Strong.¹

This is the basic finding of the report: all along, supervisors gave SVB good ratings in virtually every area, with some exceptions for governance. However, in retrospect the Fed now says a lot of things were missed. For example, "Based on the severity of the six findings from the 2021 liquidity examination . . . a more negative assessment (e.g., “Deficient-1” for Liquidity) would have been supportable."

This is typical of the report. Virtually every quantitative assessment of SVB is relatively positive, including both its capital and liquidity positions. But these are all followed by vague suggestions ("would have been supportable," "would have been reasonable," "likely not appropriate," etc.) that these assessments might have been too sunny. This makes the report extremely difficult to evaluate.

Here, for example, is one of the few quantitative assessments that's negative. It involves our old friend, the Liquidity Coverage Ratio:

An analysis of SVBFG’s December 2022 capital and liquidity levels against the pre-2019 requirements suggests that SVBFG would have had to hold more high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) under the prior set of requirements. For example, under the pre-2019 regime, SVBFG would have been subject to the full LCR and would have had an approximately 9 percent shortfall of HQLA in December 2022, and estimates for February 2023 show an even larger shortfall (approximately 17 percent).

Under the old rules, SVB would have been 9% under the LCR requirement. This may show that the old rules shouldn't have been changed, but even a 9% shortfall in one liquidity sub-metric is hardly a mark of doom.

Generally speaking, what this report shows is that SVB was basically solvent and in fairly good shape. In late 2022 the Fed began to be concerned about SVB's deposit outflow and its Regulation YY liquidity position and intended to write a warning about it, but that was far too late to have made any difference. In the event, the warning wasn't issued before SVB's failure.

Now I want to highlight the main reason I'm unhappy with this report. Here's an excerpt from Michael Barr's personal comments in the introduction:

We [] need to be attentive to the particular risks that firms with rapid growth, concentrated business models, or other special factors might pose regardless of asset size.

....We need to evaluate how we supervise and regulate a bank’s management of interest rate risk....In addition, we are also going to evaluate how we supervise and regulate liquidity risk, starting with the risks of uninsured deposits...and the treatment of held to maturity securities....We should require a broader set of firms to take into account unrealized gains or losses on available-for-sale securities.

In other words, the lesson of SVB is that we should address the very specific issues of SVB, rather than trying to figure out how—if at all—its problems were due to larger regulatory issues.

As best as I can tell, the Fed identified nothing in this report that actually led to SVB's demise. Its overall management was mediocre, but its capital and liquidity positions were generally fine with only minor shortcomings. It was arguably slow to react to its deposit outflows, but in the end it did the right thing. There was really nothing in its financials that predicted a sudden bank run.

And when the run happened, of course SVB's liquidity position became untenable. No stress test in the world can account for a sudden panic overtaking a bank's customers, and no improvements in SVB's financial position would have saved it once the run began. Quite the contrary. It was SVB's announcement of a plan to address its problems that caused the run in the first place. How do you plan for that?

¹Oddly, SVB's rating went down under the RBO rules. I don't understand this.

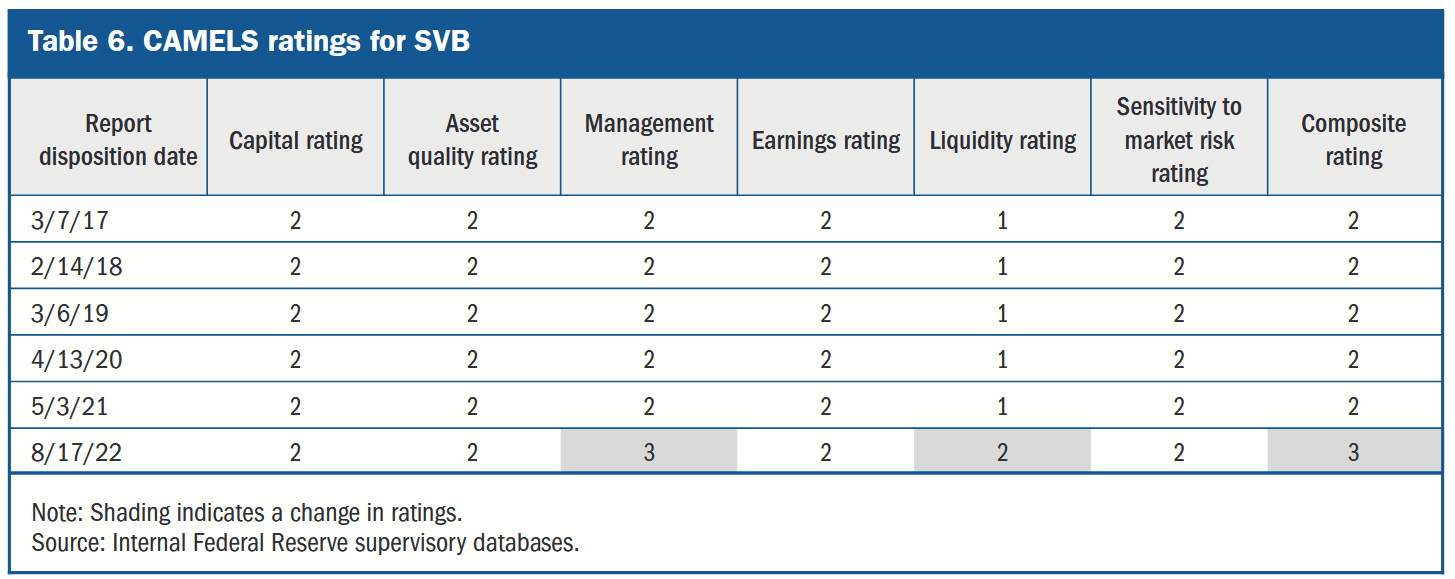

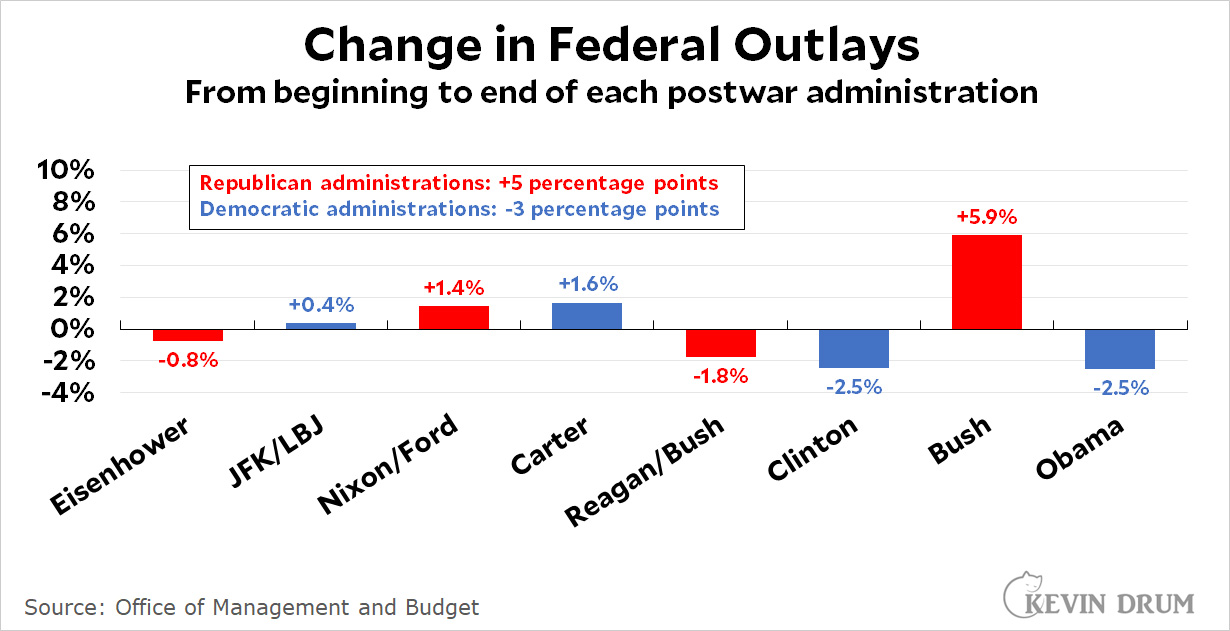

This chart shows the change in federal spending during every postwar administration.¹ For example, Eisenhower's first budget clocked in at 18.14% of GDP while his final budget set spending at 17.38% of GDP. So over the course of his administration spending declined by 0.76 percentage points.

This chart shows the change in federal spending during every postwar administration.¹ For example, Eisenhower's first budget clocked in at 18.14% of GDP while his final budget set spending at 17.38% of GDP. So over the course of his administration spending declined by 0.76 percentage points.