Over at The American Prospect, David Dayen has a good piece about the "Great Resignation," which he attributes mostly to the fact that low-wage jobs have become intolerable:

Work at the low end of the wage scale has become ghastly over the past several decades....“The U.S. needs a reset, needs a big push, to get to a place where work is more secure and livable for a lot of the population,” said MIT economist David Autor, who has tracked the misery of American deindustrialization and the shock of China’s rise as a manufacturing powerhouse.

....Quit rates and job-to-job transitions in the Great Resignation are mostly taking place among workers with less than a high school education, whose daily toil is typically spent in dead-end low-wage jobs, an engine for corporate profits that produces some of the grimmer existences in the industrialized world.

The particulars of low-wage work have been well documented for years: stagnant wages, short staffs, poor conditions, erratic schedules, no benefits, overbearing managers, and the constant fear of losing your job.

I'm never quite sure what to think of this. I agree that low-wage work in the US is pretty appalling, and it seems to be getting worse in some ways. Reports of workers increasingly being bound to computer-generated daily schedules instead of schedules worked out in advance are especially hair raising. How can you raise a family with a work schedule that you literally don't know until 24 hours in advance?

On the other hand, there's this:

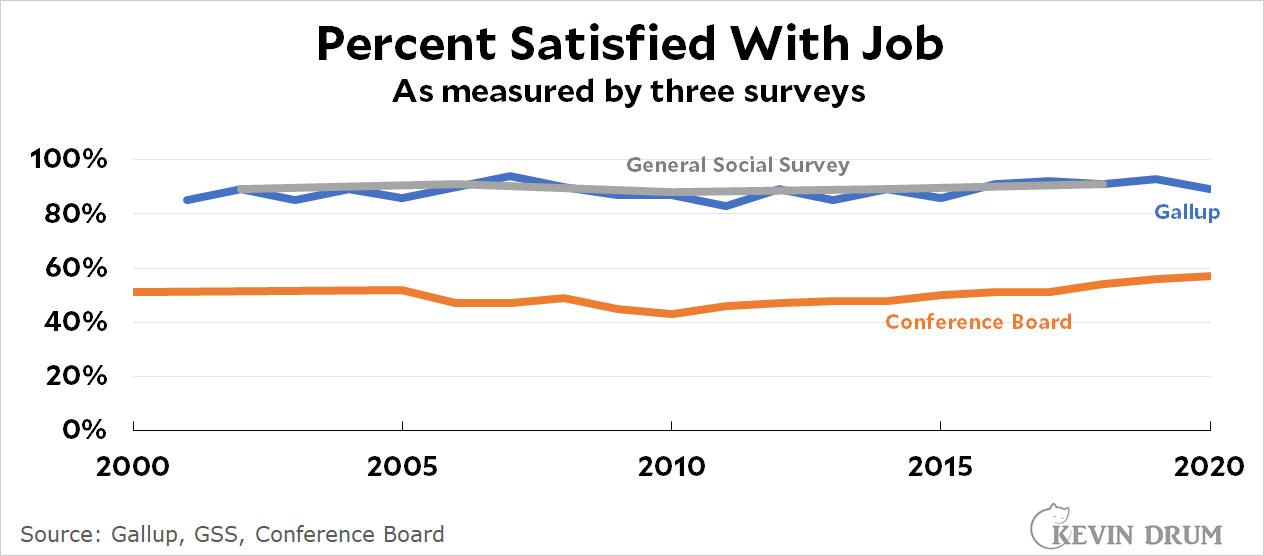

Field surveys are basically unanimous: worker satisfaction with their jobs has changed only slightly over the past 20 years, and not for the worse. The vast majority of workers are perfectly happy with their jobs, and this was true all the way through 2020.

Field surveys are basically unanimous: worker satisfaction with their jobs has changed only slightly over the past 20 years, and not for the worse. The vast majority of workers are perfectly happy with their jobs, and this was true all the way through 2020.

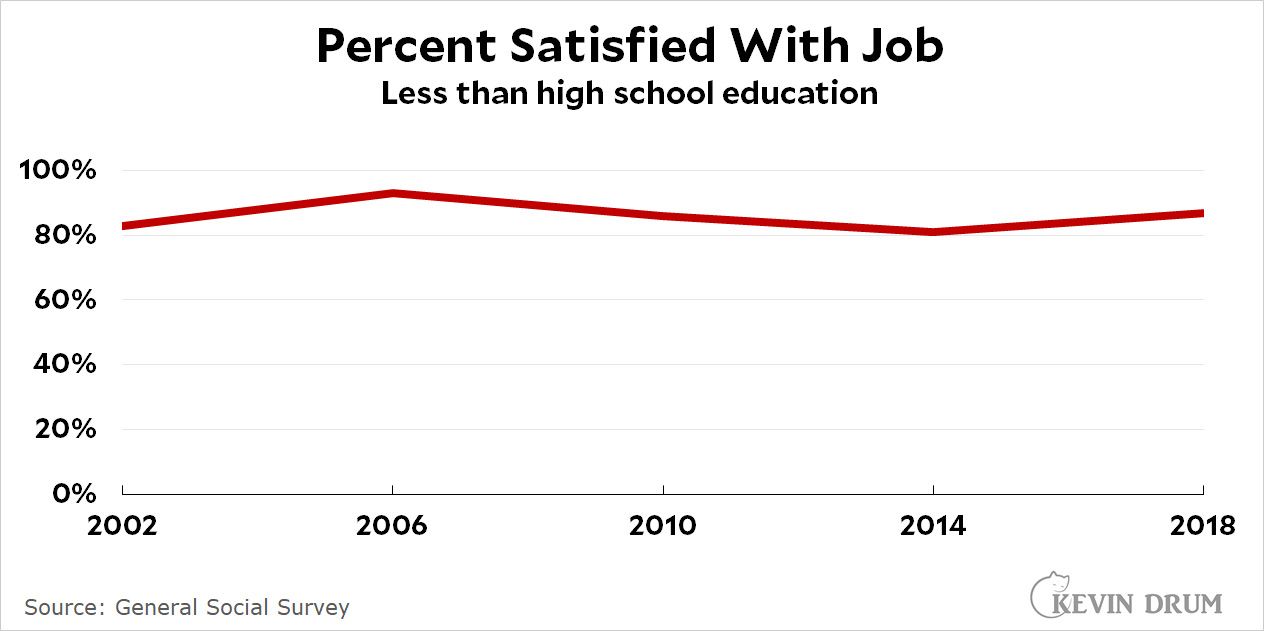

Two of these surveys don't break out results by educational level, but the GSS does. Here's what it says about workers with less than a high school education:

Again, there's not much change at all. In 2002 GSS reports that 83% of low-education workers were satisfied with their jobs. In 2018 it was 87%.

Again, there's not much change at all. In 2002 GSS reports that 83% of low-education workers were satisfied with their jobs. In 2018 it was 87%.

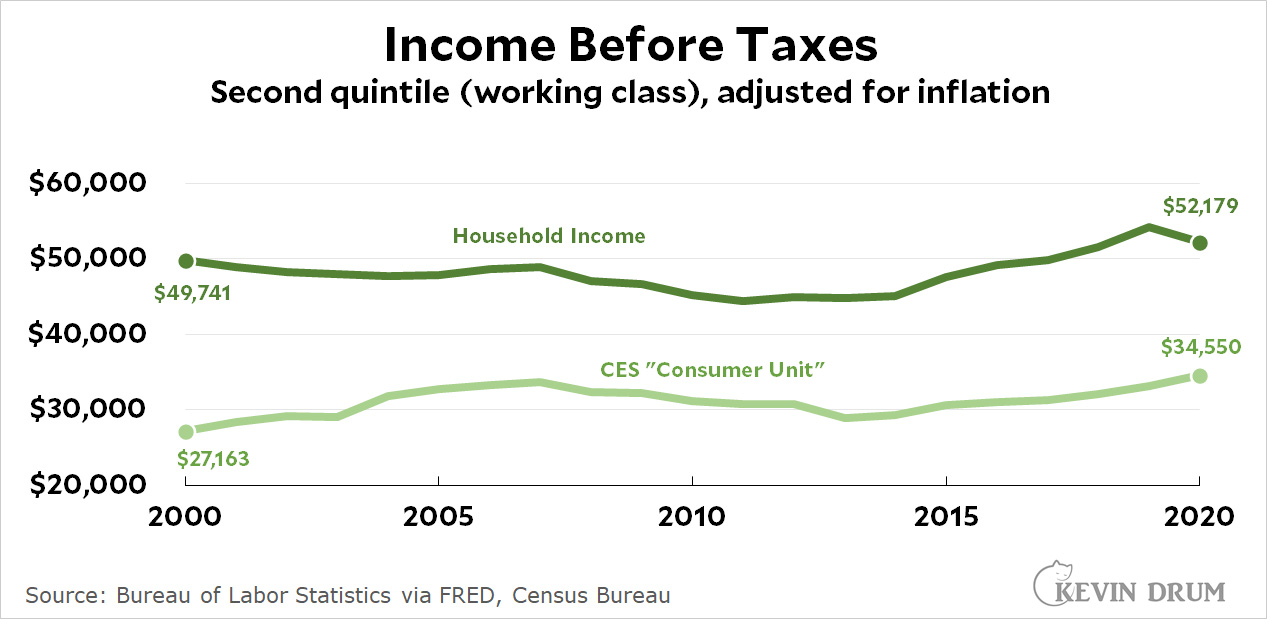

Here is earnings data for the second quintile of American workers. These are generally blue-collar workers who earn lowish middle-class wages:

These are not princely sums. Nevertheless, they've been rising since 2014 and were higher right before the pandemic than they were two decades ago.

These are not princely sums. Nevertheless, they've been rising since 2014 and were higher right before the pandemic than they were two decades ago.

(The very lowest income quintile was dead flat from 2000 through 2020.)

So I dunno. Prior to the pandemic there was no real evidence that workers were especially unhappy. Just the opposite, in fact. So what's really going on? Are surveys unreliable indicators? In retrospect, have low-income workers decided they were less happy than they thought at the time? Are they sick and tired of pandemic working conditions and eager to switch jobs just for a change of scenery? Is it nothing more than a year's worth of normal job restlessness all squashed into a few months? Or what?

Most people I know are pretty happy at their jobs and only leave if there is conflict with managers or co-workers and their is a better opportunity.

I just think the media environment and the pace of economic and technological change are making people a bit stressed out.

Maybe the turn towards authoritarianism in the USA is in part not so much racism and animosity towards others and more just people wanting the change to stop or not having to worry about it?

Depending on the survey, you have 10 to 40% who aren’t satisfied. Even if overall satisfaction hasn’t changed, if half of that 10% decide they’re not putting up with it any more that’s millions of people quitting and staffing shortages for those jobs. So you need some way to look at whether attitudes have changed among the unsatisfied people.

And if it goes down in the next year, it was probably a business cycle thing due to the fact recovery.

My guess is that a lot of people in this category were unemployed during the pandemic, which weakened their psychological attachment to the labor force. Now they are, for a time, in the same condition as new entrants to the labor force have always been, i.e., weakly attached to their jobs and manifesting high turnover. With a little time, most of them will settle down, as new entrants to the labor force normally do. Most people--this is true at every income level--stay at their jobs because they have job-specific expertise, they have friends at work, and they have found ways to derive pleasure from what they do. Those things often take time to develop.

"Is it just a year's worth of normal job restlessness all squashed into just a few months? Or what?"

Or is it just a case of the universal law of perpetually shifting baselines ?

Test

In retrospect, have low-income workers decided they were less happy than they thought at the time?

Paul Krugman a few weeks back was citing the work of an economist (name escapes me) who has come to exactly that conclusion. Apparently (IIRC) there's substantial evidence blue collar US workers underestimate how poorly compensated they are relative to other workers (white collar? overseas?). Inconveniently for American capitalism, the pandemic, so goes the reasoning, has upset the apple cart of US worker obliviousness.

What he said.

As a person who had been and is now once again a member of the low wage/skill group, I believe that a lot of the workers who say they are “satisfied” are just accepting their situation and believe that their only option is unemployment. So, yeah, “the job ain’t so bad.” But one thing the pandemic did was force a lot of these workers to pause, take a step back and discover, to their surprise, that they had more options than they realized existed.

At my job, we have lost a lot of people in the past year, year and a half, and all the escapees I knew moved on to jobs that they considered “better” for one reason or another. (Those of us left behind are very much overworked and are able to work almost as much overtime as we are willing to do. Those very few who have considered joining our merry band either didn’t show up for their final interview or failed the drug test. The one and only person who has joined us in about 2 years is an immigrant who’s happy just to be relatively safe in this country.)

Those people who left may have been “satisfied” just to have a job, any job. But they were not “perfectly happy”. Once they saw how things could be better, they left. And I don’t blame them.

More generally with survey questions like that one, the results show how people respond to that string of words. What, if any, deeper meaning is to be found from these responses is often obscure. This is why it is so important that the exact same string of words be used year after year. If the responses were to the meaning of the question, a differently worded question with the same meaning would evoke the same response.

Of course workers have a different attitude - temporarily - because they were getting money without working. And of course the stimulus checks and unemployment increases have played a role - there is no reason to expect the effect of these things to stop the instant that the payments do. Many people saved some of the money and there are still rent moratoriums in many places and also rent subsidies to be distributed. Workers may be able to hold out for a while for better jobs. But the effects of the massive stimulus bills will run out before too long and there is no reason to think there has been a fundamental change in the worker/employer balance. Actually some big business have increased their wealth and power considerably, while many small employers, which employ a lot of people, have gone out of business. Exactly what the employment situation will be when covid is over (if it ever is) remains to be seen, but there is really no reason to think that workers suddenly decided that they will deliberately withhold their labor if they don't get better wages and conditions, however dissatisfied they may be. If they run out of money they will take whatever jobs are available, just as before.

Stop using the financial aid as an excuse. For the vast majority of people, it wasn’t enough to replace a paycheck. Many of the low wage jobs I know of in Denver have already substantially improved the pay and conditions for workers. *That* is what will get the workers to maybe return. (One example: one of the local fast food chains that paid $8-9 an hour before the pandemic has signs up front now begging people to come work for $17 or more an hour. For now, some of the fast food joints close at sundown and put out signs saying that they are closed because they don’t have enough workers. Forced me to drive around looking for a place I liked that was open.)

Yesterday I had a conversation with an hourly guy where I work (I'm salaried professional) and he indicated that he was waiting to hear back from a prospective employer. More money and no weekend work. He's not quitting the workforce, just changing jobs. Later in the afternoon I attended a retirement celebration for another colleague.

I think the pandemic upended peoples job lives enough to motivate them to change. I considered moving to a new job myself these past couple of months. Instead, I am changing jobs internally with my employer.

I don't think polls about job satisfaction are capable of picking this up on these sorts of trends.

According the the Wall Street Journal REgeneron is also reporting that its treatment is a LOT less effective against Omicron as well

Poor Ron DeSantis - I wonder how long he will push regeneron therapy to his constituents at $2500 a treatment?

Yeah, but how effective is livestock dewormer? I think that's what we're all waiting to hear.

"So what's really going on? Are surveys unreliable indicators? In retrospect, have low-income workers decided they were less happy than they thought at the time?"

That seems likely. The most obvious explanation here is that one's response to a survey about job satisfaction isn't strongly correlated to the likelihood of one quitting in the near future. It could be that that survey is measuring satisfaction with the economy in general. Or it may be measuring noise.

If I had a social scientist near to hand, I'd ask if there's any good evidence that those survey responses correlate to anything at all, and if so, what.

Maybe don't conflate "satisfied" with "perfectly happy".

What I'd like to see is whether/how much the labor force has really shrunk. I understand that quits and hires are up, which is expected. But for there to be a labor shortage the workforce needs to have shrunk, or business needs to have decided that they need more workers.

And let's not forget that several hundred thousand workers are now dead due to Covid -- not a huge percentage of the overall workforce to be sure, but especially early in the pandemic, a lot were low-wage workers in "essential" industries like food service, meatpacking, nursing home care, etc.

This seems to ignore undocumented workers who are virtual slaves because they have no judicial rights. If low wages prevent many citizens from taking jobs, those jobs will go to undocumented workers who become virtual slaves. BUT when minimum wage laws force employers to pay higher wages more of the jobs will go to citizens who then protest the poor working conditions.

Rights???? Who cares. They are scabs of capitalism. Respect for themselves, they do not have.

If you don't understand how bad it is you should spend some time in https://www.reddit.com/r/antiwork/.

Addendum

Regeneron is ACTUALLY TESTING against omicron, not theorizing according to their statements. And they are saying preliminary DATA suggests they will need to re-tool their formula

Exactly what reason is there to believe in, or care about, the opinions of the punditocracy regarding the thoughts and motivations of the US working class?

People like David Dayen have mispredicted their politics, their concerns, their interests, since at least the Reagan Revolution, with Trump and Brexit as merely the most recent iterations.

Is there even a real phenomenon here as opposed to a few anecdotes being turned into a huge claim about the state of the world? It certainly doesn't give one confidence that the article can spare some space for a medieval picture -- but not for a graph or three...

The number of unhappy workers may be stable, but the passion of the unhappy has increased from disgruntled to raging. Same group getting screwed, but harder.

Pingback: Die Washington Post schreibt homöopathischen Unsinn über linke Kritik an deutschen 520-Euro-Bildungsplänen - Vermischtes 01.12.2021 - Deliberation Daily

Pingback: Weekend link dump for December 5 – Off the Kuff