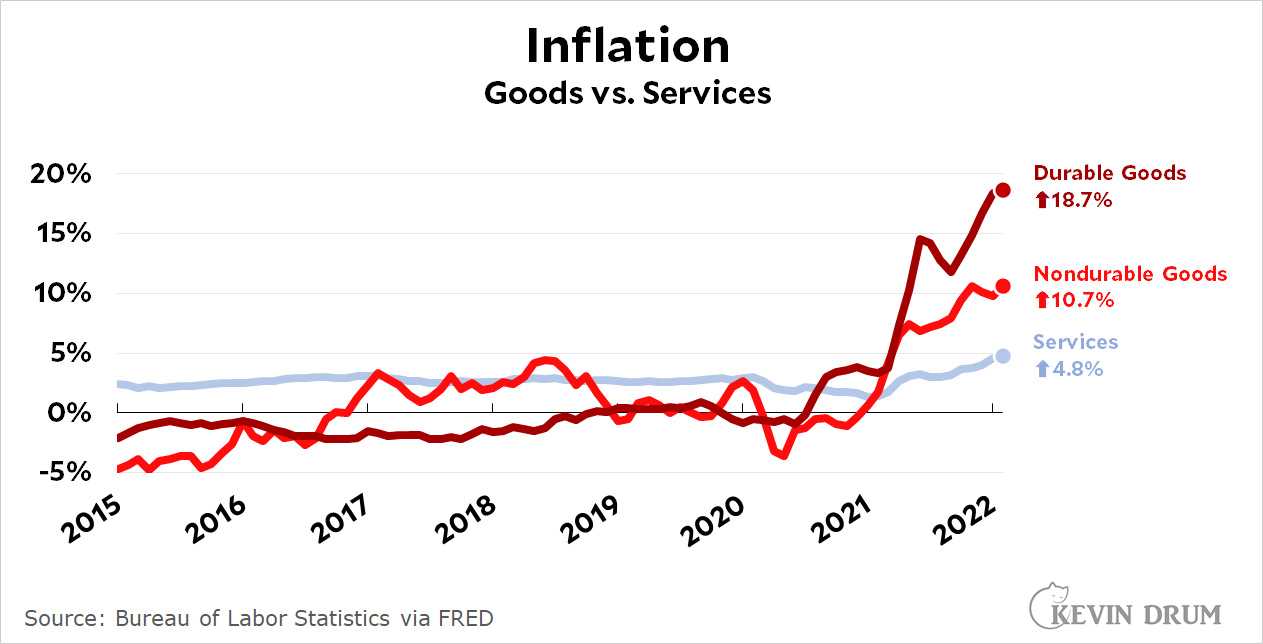

Normally, the inflation rate of goods and services are roughly similar. But no longer:

The inflation rate of durable goods has skyrocketed, and instead of being a few points below the inflation rate of services it's now 14 points above the inflation rate of services.

The inflation rate of durable goods has skyrocketed, and instead of being a few points below the inflation rate of services it's now 14 points above the inflation rate of services.

One way to think about this is that the inflation rate of services is sort of a baseline rate for overall inflation because it's not strongly affected by supply chain issues. If that's the case, the underlying rate of inflation in the economy is around 4-5%, with the rest caused by temporary shortages of goods.

If this is the case, then the current inflation rate can be broken down approximately like this:

- "Normal" underlying inflation: 2%

- Fiscal boost: 2-3%

- Shortages: 2-3%

If this is a good model, inflation will subside when the fiscal impetus of the rescue bill fades and will then subside further when the supply of goods catches up to demand. The "transitory inflation" crowd believes this should happen before the end of the year. The "crisis" crowd believes it will take longer than that and will eventually produce a wage-price cycle that could last for years.

How probably is a wage price cycle in the age of powerless labor unions? I just don't see it.

So far wages have not followed inflation at all, have they?

I agree with azumbrunn. There can be no "wage-price spiral" when employers hold all the cards. They'll just automate anything that they can't find people to do.

Stop spending money on junk. Problem solved. I don’t need any new junk.

What a brilliant idea! People who need stuff should just go without, because you've solved the problem by determining that stuff isn't necessary (for you? and thus presumably for other people?).

I'll let my brother in law whose car got totaled know that he really isn't suffering any hardship from high vehicle prices because he can just choose to not spend money on junk!

I won’t buy a new car this year so you and your reckless relatives can replace yours. You’re welcome.

Junk defined. Since you are too dense to understand.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/31/business/supply-chain-small-business.html

Prices would have to stabilize, or better yet drop, starting now if the lower inflation rates were to register with people prior to Nov elections. A drop by the end of summer may be too late for people to "feel" it.

The model is interesting but may I suggest challenged:

1. The model assumes the removal of fiscal boost with the end of stimulus programs. Many economists, recently Larry Summers made this point on the Ezra Klein show, the impact of the stimulus last several years.

2. The model does not account for fiscal stimulus. Fed Funds rate at 4%, versus near zero, has a huge impact on the economy.

3. The model does not include expectations: what I think of future inflation changes my current behavior.

Re 2., I think you mean monetary, not fiscal policy (and of course Kevin did address fiscal stimulus). But research has not demonstrated ‘huge’ effects of small changes in interest rates.

Re 3. Behavior is determined by more than expectations. The ‘expectations’ mechanism assumes that people purchase sooner, to avoid future price increases, but if your purchasing power isn’t increasing (see azumbrunn and Anandakos above), your ability to do so is constrained.

KenSchulz - thank you as you are correct, I INTENDED to write monetary policy.

While we may not agree on the economic dynamics, we will see what the next couple of years hold economically speaking...

The moderate price increase on the service side is certainly a strong case against the argument that the economy is overheating and demand side measures (fiscal stimulus, federal reserve) are to blame. Given this, its not really clear that raising interest rates and removing fiscal stimulus will be a positive for the economy and the people of the United States.

Kevin's analysis is as good as anyone's as far as it goes, but it leaves out oil price. Oil price is what caused the inflation spikes of 1975 and 1980. There was no wage-price spiral - wages did not increase nearly as fast as inflation and real wages crashed as those inflation spikes rose. Inflation came down instantly when oil price quit rising, not when the Fed beat down the uppity workers' wage demands. These are facts which anyone can look up in the data at FRED. Inflation also came down instantly when oil price did in 2008.

So the longer-term risk of inflation is from further constrictions in oil supply, though the system is probably more resilient now. Of course we may not be done with covid yet, so we could still have more supply-chain problems. But apparently there won't be any more stimulus, so that addition to demand will be absent. Without stimulus there would probably be contraction in demand in case of more pandemic restrictions.

If this damn horse would die, I could stop beating it. The trouble with using the word ’inflation’ when one discusses sectoral price increases, is that it predisposes one to fixate on the non-solutions of fiscal and/or monetary policies (the former being government deficit/surplus, the latter being FOMC interest-rate setting). Inflation is a loss of value of a currency, which will be seen as a rise in ‘all’ prices (superimposed on sectoral changes), and is properly dealt with through fiscal and monetary policy. Excessive sectoral price increases need sectoral solutions, depending on the cause, which can be quite varied - natural disasters, monopolistic price-fixing, war, pandemic disease, weather …. Fixes are varied also - substitution, adding sources of supply, developing alternatives, breaking up monopolies, increasing efficiencies in production and distribution ….

Economists got it into their heads in the 60's that interest rates and monetary policy in general could solve any problem, and apparently no amount of evidence can convince them otherwise. Rather than acknowledge that the problem is oil price or supply chain issues or whatever they just mindlessly suppose that increasing interest rates will do the trick. But of course this approach failed utterly in the 70's.

+1

Agree with azumbrunn and Anandakos; no wage-price spiral possible given labor’s weakened state. Agree with jdubs that raising interest rates sharply is not going to help. If the problem is ‘too much money chasing too few goods’, well, higher energy prices will take away money that would otherwise be chasing goods. And, as higher energy prices are exogenous, they aren’t driving a feedback loop.

Throughout 2021, Kevin was telling us there was no serious threat of inflation - that all the numbers were transitory, not indicative of the "true" inflation rate, and to ignore many UI stats because (fill in the blank). And here he is again, reassuring us that the best case, "transitory inflation", even if big, is obscuring the fact that "normal" inflation is a low, low, 2%. So relax everybody.

I guess, given the pandemic uncertainty, it would have been better to let people starve and suffer until it was clear the effect. And look, these programs to provide support wee looted by criminals anyway. Now that we have some other external force causing economic pain, we should not react. Let the poor suffer. Right?

Here is what Larry Summers told Ezra Klein (in part):

"The situation continues to resemble the 1970s, Ezra… mistakes of excessive demand expansion that created an inflationary environment. And then we caught really terrible luck with bad supply shocks from OPEC, bad supply shocks from elsewhere. And it all added up to a macroeconomic mess. And in many ways, that’s the right analogy for now. Just as L.B.J.‘s guns and butter created excessive and dangerous inflationary pressure, the macroeconomic over-expansion of 2021 created those problems, .... " Good to know where the other guys are coming from.

The wage spiral threat ignores the long-term threat of the ZLB and deflation from loss of consumption demand. As Japan hit its deflationary period, it was the aging population that drove the ZLB. As BB retire, incomes drop. Watch.

Is there any evidence that "peak everything" is a factor in inflation?