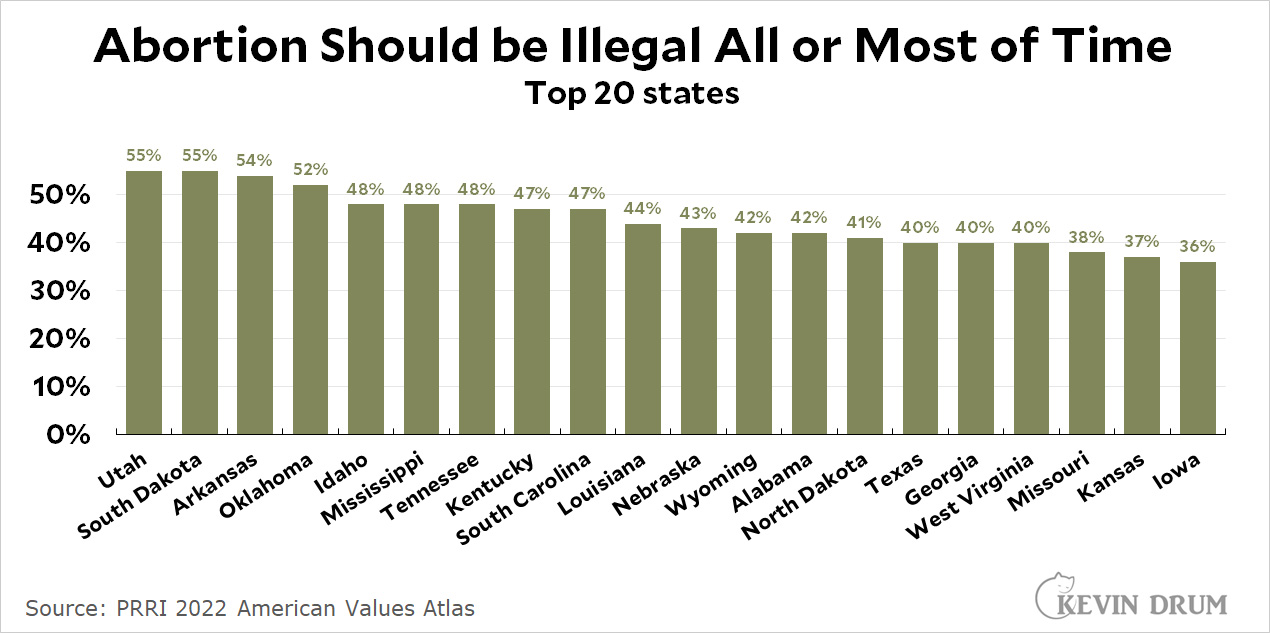

We all know that abortion rights tend to be popular at a nationwide level—even more so following the Dobbs decision. Most polling suggests that around 60% of Americans think abortion should be legal all or most of the time.

But nationwide doesn't matter since Dobbs made abortion a state matter. Abortion is now banned, or mostly banned, in a dozen states throughout the South plus a handful elsewhere.

But are abortion bans popular even in these states? This is where things get curious. We don't have a lot of state polling, but we do have one comprehensive poll: a survey of all 50 states done in February by PRRI. Here's what it looks like:

I can't say for sure how reliable these numbers are, but they sure seem to suggest that abortion bans are not especially popular even in deep red states. In only four states is there even a bare majority that thinks abortion should be banned all or most of the time.

I can't say for sure how reliable these numbers are, but they sure seem to suggest that abortion bans are not especially popular even in deep red states. In only four states is there even a bare majority that thinks abortion should be banned all or most of the time.

Other states are even weaker. In Texas, one of the most aggressive states to ban abortion, only 40% of residents think abortion should be illegal all or most of the time. In Florida it's only 33%. No wonder Ron DeSantis dithers so much about acknowledging the abortion restrictions he signed into law.

In all of these states there are conservative Republican majorities against abortion, and obviously that's the only thing extremist Republican legislators care about. Nevertheless, this polling explains why pro-abortion referendums often succeed even in red states: when everyone votes, they have pretty clear majority support. It's only when the zealots can ignore half their constituents that abortion bans have a chance. Unfortunately, history suggests they can keep ignoring them for a good long while.