A couple of years ago I became pretty skeptical of the panic over social media. No matter how obvious the harms of social media might seem, especially to us oldsters, the evidence just wasn't there. This became especially obvious to me in late 2021 when the media wildly misreported the leaked Instagram survey of teen boys and girls. In fact, in my year-end list of bad trends, I included this one:

Blaming everything on social media. This really ought to stop. There's very little rigorous evidence to back it up, and quite a bit to suggest that social media is a net positive.

Jonathan Haidt has been on the opposite side of this argument for a while, and yesterday he criticized the kinds of objections people like me raise about the evidence of social media harms—primarily that the actual research is thin and inconclusive:

Those were reasonable things to write in 2019, but not in 2023. We now have dozens of experiments, plus some very consistent and incriminating patterns in the hundreds of correlational studies.

Maybe so! This is not a subject I follow obsessively, so maybe things have changed. Haidt referred me to his congressional testimony from last year for more, so I read it.

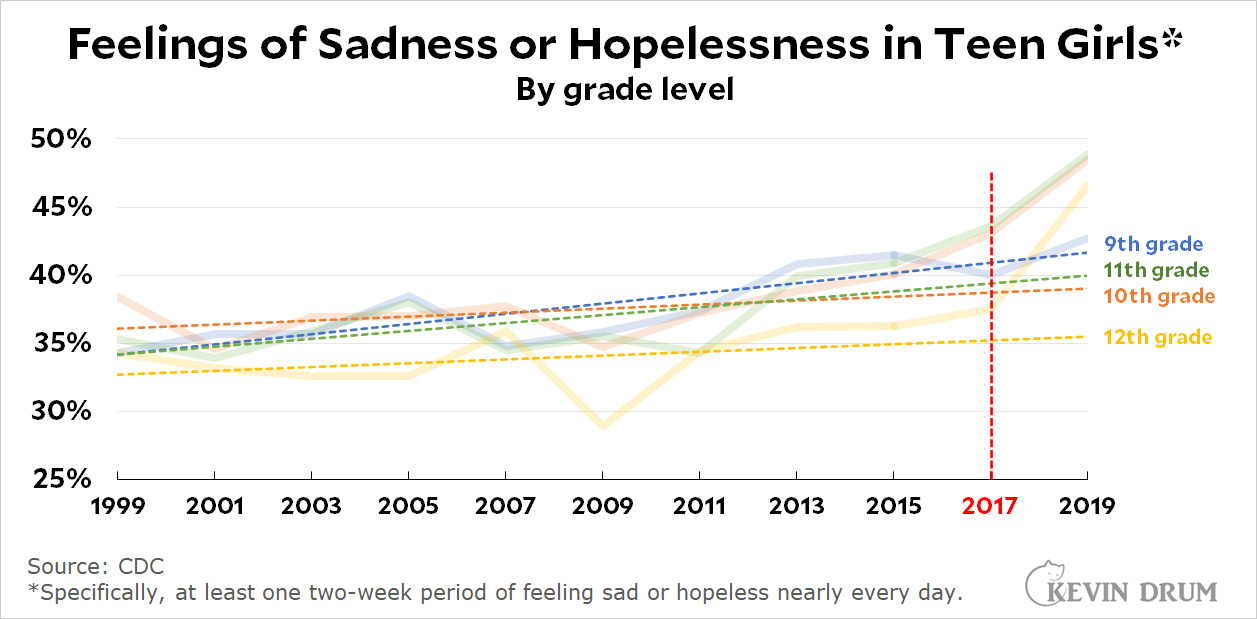

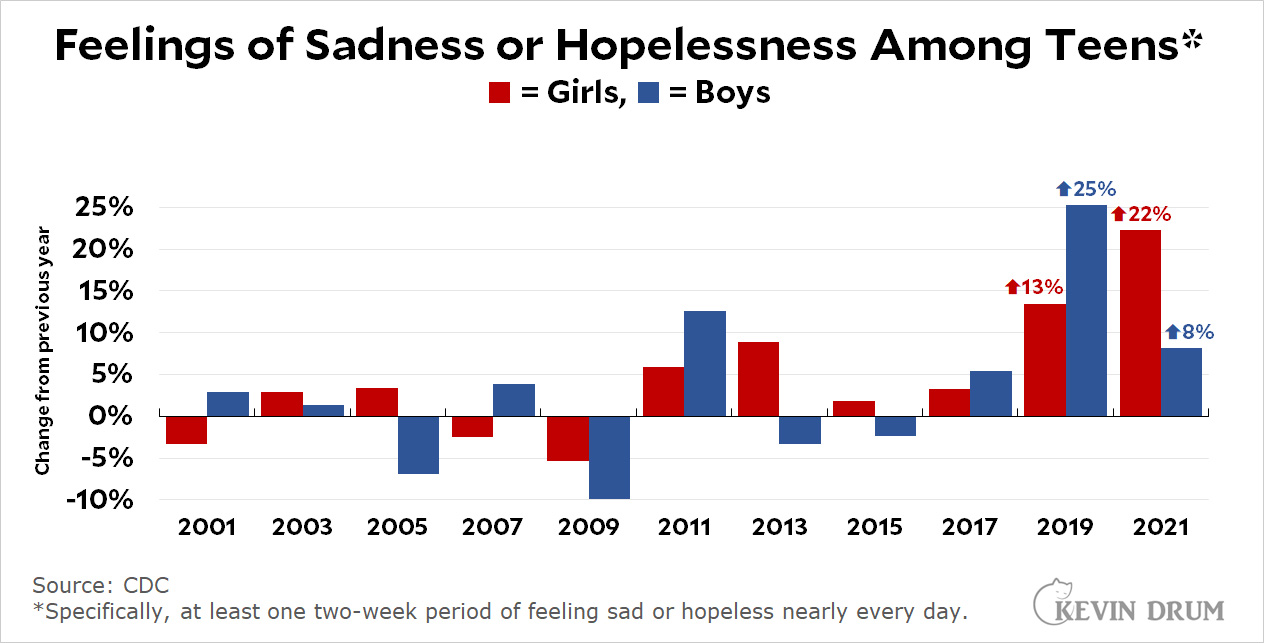

For a while I was nodding along as Haidt produced a bunch of charts showing a steady rise in anxiety and depression among teens starting around 2012. But then there was this:

“The associations between social media use and well-being therefore range from about r = − 0.15 to r = − 0.10.” I agree with this assessment, for both sexes combined....A ballpark figure for the correlation just for girls is roughly r = .15 to r = .22. The effect size is even larger for girls going through puberty....For them, the size of the correlation with poor mental health could be well above r = .20.

This requires a translation from math to English. Here it is:

- Overall, social media can explain about 1-2% of the difference in well-being among teens.

- Among girls, it explains 2-4%.

- For girls going through puberty it "could" explain more than 4%.

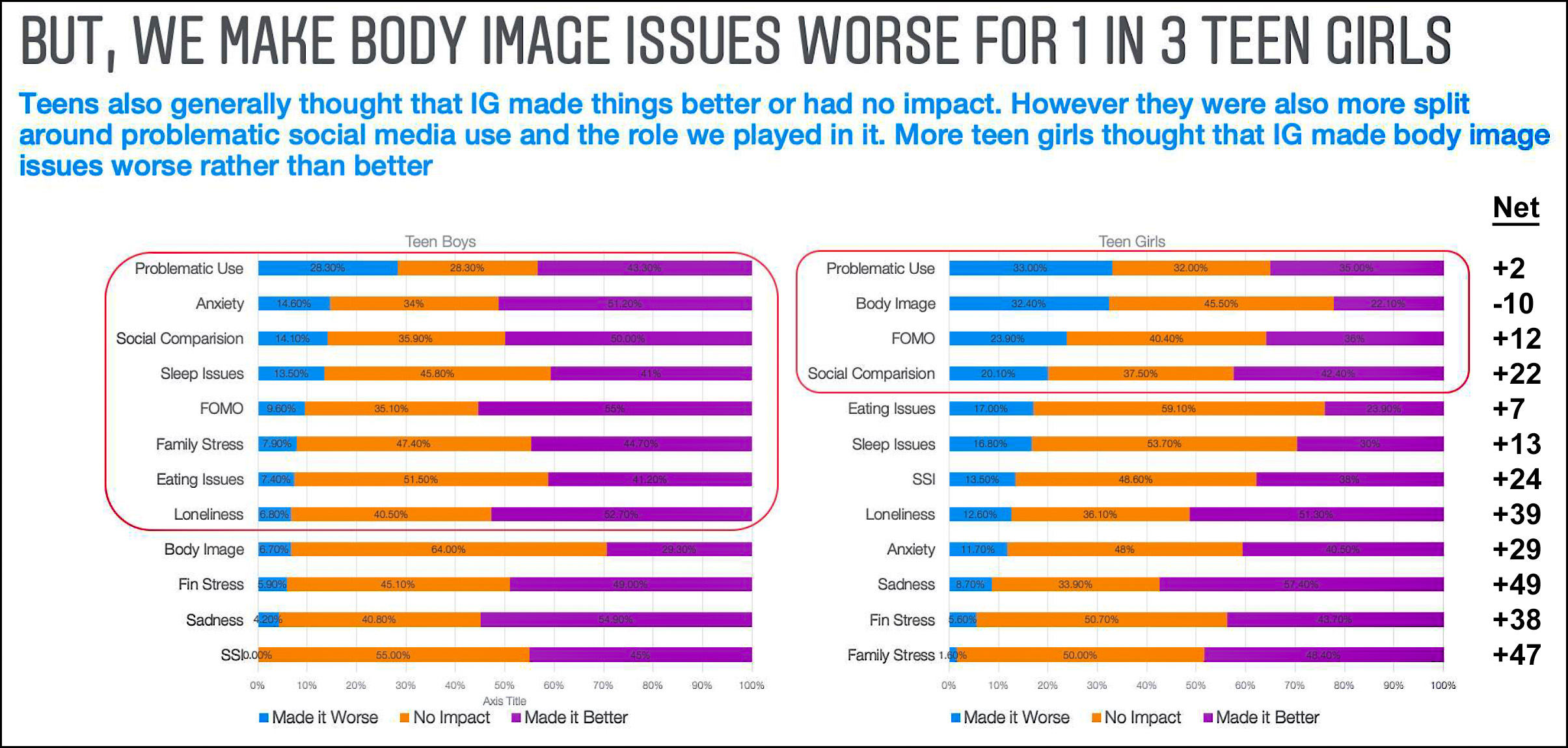

As Haidt points out, 2% is low, but it's not nothing. And as he also points out, his concern is solely about the effect of social media on mood disorders like anxiety and depression. However, even limited to mood disorders it's hard to square this with the infamous Instagram survey that got so much attention in 2021:

Teen girls report that Instagram had a net +39% effect on loneliness; +29% on anxiety; and +49% on sadness. On all three measures, only about 10% of teen girls reported that Instagram made things worse.

Teen girls report that Instagram had a net +39% effect on loneliness; +29% on anxiety; and +49% on sadness. On all three measures, only about 10% of teen girls reported that Instagram made things worse.

So . . . I dunno. I'd offer up a few tentative conclusions:

- Even Haidt limits his criticism to depression and anxiety, mainly among girls, but in the popular press this too often gets translated into a generalized panic about social media having a bad effect on nearly everything. Kids these days don't know how to use a salad fork! Blame Facebook! This is just wrong.

- Even if Haidt is correct, the size of the effect on teen depression is quite small.

- It also appears that social media has a negative effect only in large quantities. A couple of hours a day is unlikely to change anything.

- Most likely, the biggest effect is on teen girls who already suffer from depression and then begin to obsess over their social media accounts, which makes them even worse off. If this is the case, it's counterproductive to panic over social media in general. The thing to watch for is depressed teens who suddenly start spending five or six hours a day on social media. That may be the sign of a dangerous downward spiral.

You can see from this why I called yesterday's CDC report kind of mysterious. It's one thing to look at trends in teen depression since 2012 and conclude that social media has played a role. It's quite another to explain a huge jump starting around 2019. The effect of social media is simply too small to account for it, and the timeframe makes no sense anyway. So it remains a mystery.

POSTSCRIPT: All this said, my gut agrees more with Haidt than my brain. For what little it's worth, here's a few pieces of advice for parents:

- It's not really feasible to keep teens away from social media, but it's probably a good idea to keep them away at least until age 14.

- Absolutely have no guilt about insisting that you have access to their accounts and will check in on them periodically.

- That said, don't check in all that often.

- Try to persuade your kids not to follow too many people. This is what causes phones to demand attention constantly.

- Take their phones away at night. That goes for you too.