On this 990th Easter Sunday, let us take to heart Christ's teaching on poverty and wealth. His messages, often veiled in the form of parables, are crystal clear on this subject:

Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God....But woe to you who are rich, for you have already received your comfort.

Luke 6:20, 24

This week, mammon responded with a similar homily:

One practical approach to implementing weights that account for diminishing marginal utility uses a constant-elasticity specification to determine the weights for subgroups defined by annual income. To compute an estimate of the net benefits of a regulation using this approach, you first compute the traditional net benefits for each subgroup. You can then compute a weighted sum of the subgroup-specific net benefits: the weight for each subgroup is the median income for that subgroup divided by the U.S. median income, raised to the power of the elasticity of marginal utility times negative one. OMB has determined that 1.4 is a reasonable estimate of the income elasticity of marginal utility for use in regulatory analyses.

Fucking government. They have to bollox everything up into some kind of incomprehensible gibberish, don't they? But I'm here to help. This is part of a new proposal from the OMB, charmingly named Circular A-4, about how to do cost-benefit calculations. The old system was pretty simple: if a new proposal benefited you a dollar but cost me a dollar, the cost-benefit was zero. In the new proposal:

- OMB recommends that we account for diminishing marginal utility. This is the fact that the more money you have, the less each dollar means to you.

- To account for that, divide your income (and mine) by the median income.

- Then raise those numbers to the power of -1.4.

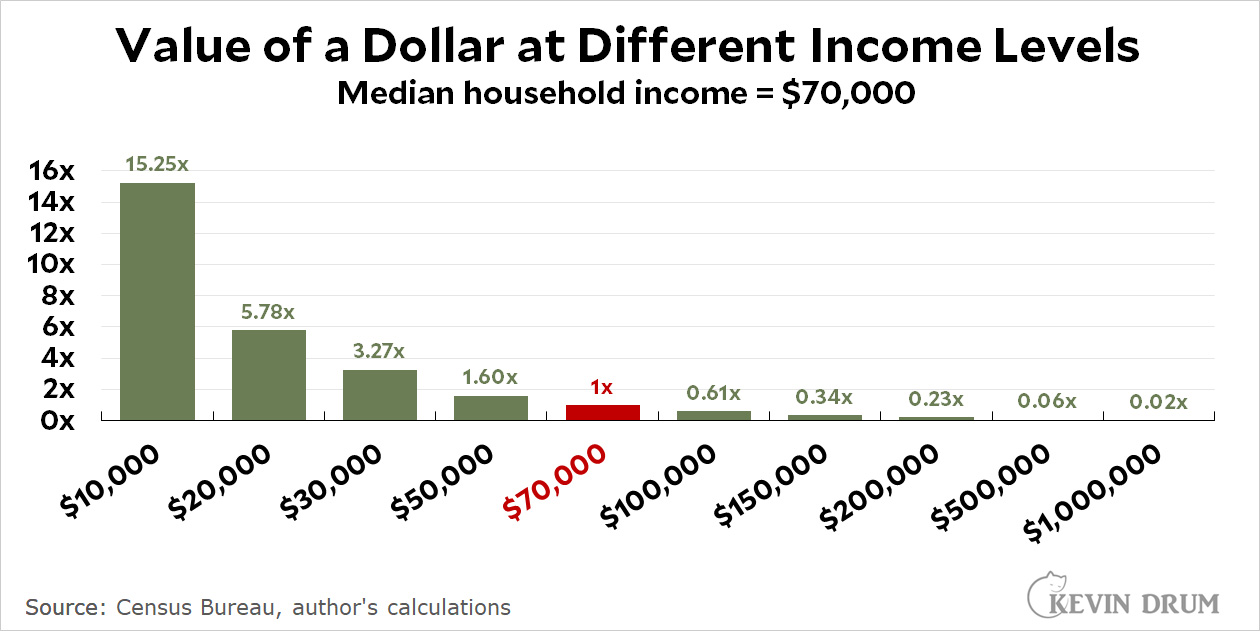

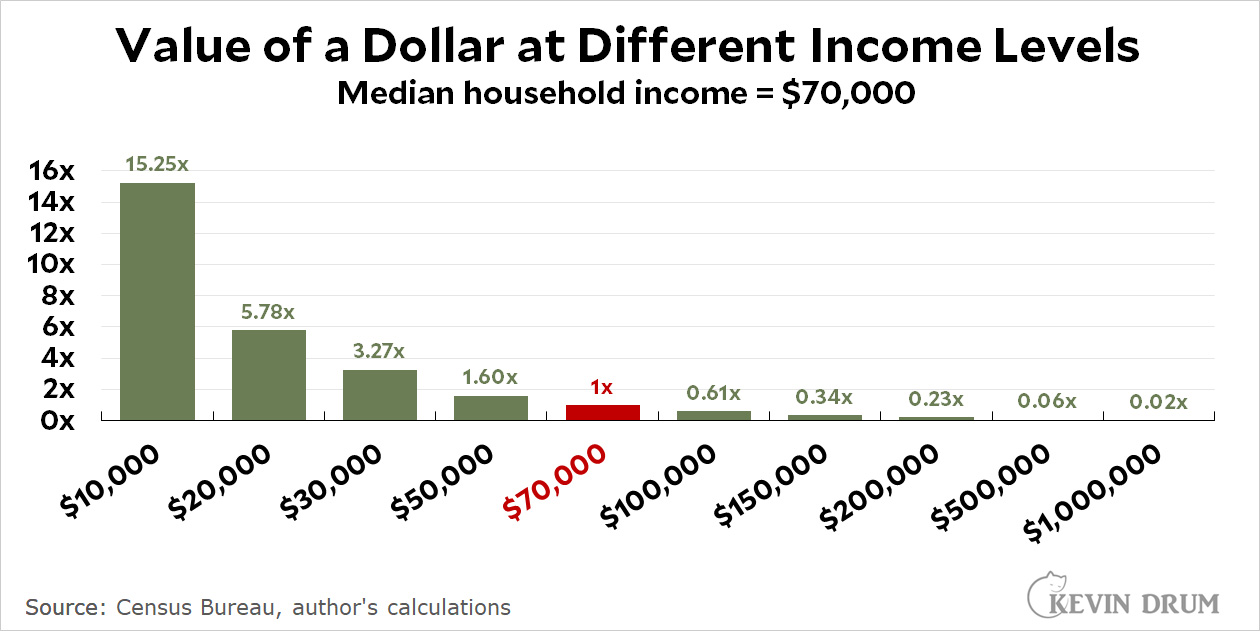

Still confused? Here's a handy chart showing how much a dollar means to you depending on your income:

The median household earns $70,000, so it gets a weighting of 1.

The median household earns $70,000, so it gets a weighting of 1.

But if you're working class and earn, say, $30,000, an extra dollar is worth $3.27 to you. Conversely, if you're upper middle class and earn $200,000, an extra dollar is worth only 23¢.

So if I'm evaluating a new government program and it improves the life of a working class person by $10, that's a benefit of $32.70. If I take away $10 from an upper middle class person to pay for it, the cost is $2.30. Instead of a cost-benefit of zero, I have a whopping positive cost-benefit of $30.40.

This is via Noah Kaufman, who has (apparently) read the entire 91 pages of Circular A-4 and says:

This new guidance on capturing distributional concerns is the show stopper. Because this isn't just an assumption tweak. It's an entirely different approach to cost-benefit analysis.

Releasing this new guidance on a holiday weekend has kept it under the radar so far, but that won't last long. Needless to say, the usual suspects will have something to say before long. I predict that they will be very pissed off.