Dan Wang writes this week about Xi Jinping's increasing obsession with controlling every aspect of Chinese society and the impact this has on the already parlous state of China's technology sector:

The general political environment poses perhaps the greatest threat to technological momentum....I grow less certain that a third-Xi term China will sustain an innovative drive.

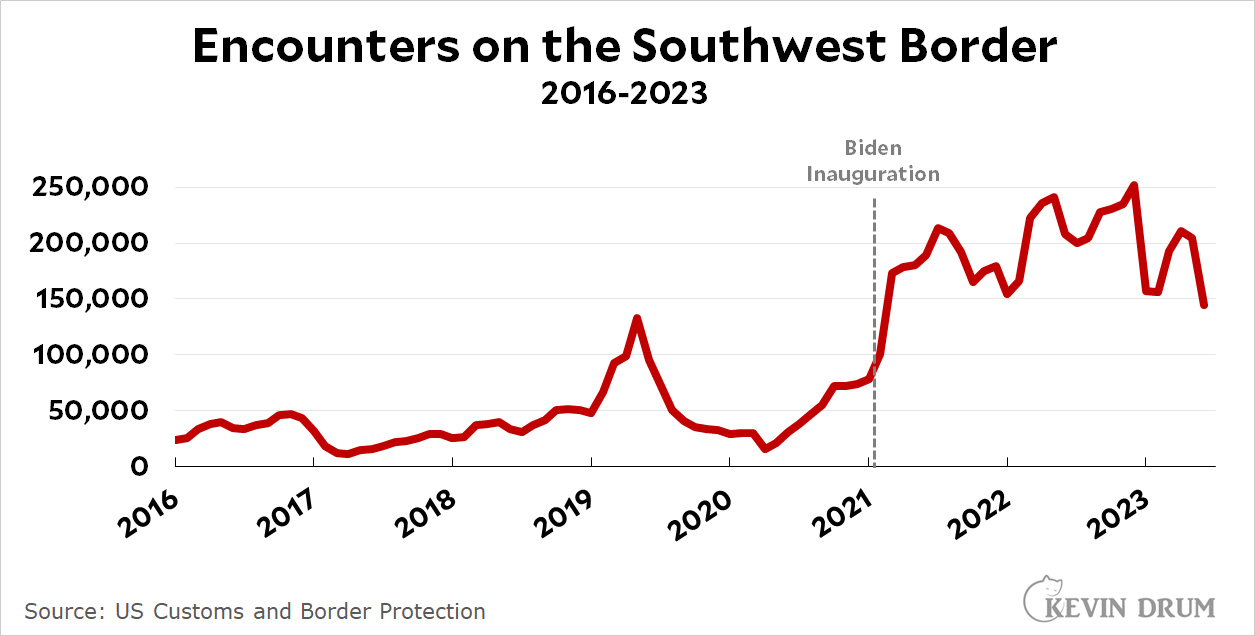

A lot of entrepreneurial Chinese are unsure too. The most startling news story I read this year is that rising numbers of Chinese nationals are being apprehended at the Mexican border, trying to make the crossing into the United States. I had not imagined that some Chinese would find such a harrowing trip to be worthwhile. That comes on top of the well-reported trend that many Chinese entrepreneurs have decamped to other markets. In the last few months, I’ve chatted with a good number of Chinese undergrads in the US, who almost to a person tell me that their parents are urging them not to return to the mainland. These groups make up a miniscule percentage of China’s population. But tech development depends on them too.

This dim view of China's technological progress shows up in patent activity as well. We've all seen the charts showing Chinese patent applications skyrocketing, but those are badly misleading for two reasons. First, China employs a subsidy system that encourages inventors to file meaningless patent applications, which results in impressive but ultimately hollow numbers. What matters is patents granted. Second, unlike the US, China grants a very large number of design and "utility" (i.e., small incremental) patents. But the patents that matter are "invention" patents. Here's what that looks like:

The US grants four times as many serious patents as China. What's more, US patents are of far higher quality:

The US grants four times as many serious patents as China. What's more, US patents are of far higher quality:

Another measure of patent quality also leaves China far behind the US:

Another measure of patent quality also leaves China far behind the US:

Only 4.17 percent of 1.2 million Chinese patent applications were filed overseas, and 6.31 percent of the total patents were granted in foreign countries. Conversely, 43.40 percent of 521,802 U.S. patent applications were filed overseas, and 48.10 percent of the total patents were granted in foreign countries.

There are several reasons why Chinese companies file so few foreign patents, but one is that China's lower-quality patents are unlikely to withstand international evaluation.

If you put all this together, China doesn't look like a technological powerhouse. They have plenty of world class research, but it's focused in very specific areas that are often mandated by the central government, leaving important areas such as biotech, AI, and semiconductors as backwaters. As with so many things China, a dynamic facade disguises the fact that it's basically still a developing country and the US remains about six times wealthier and more productive.

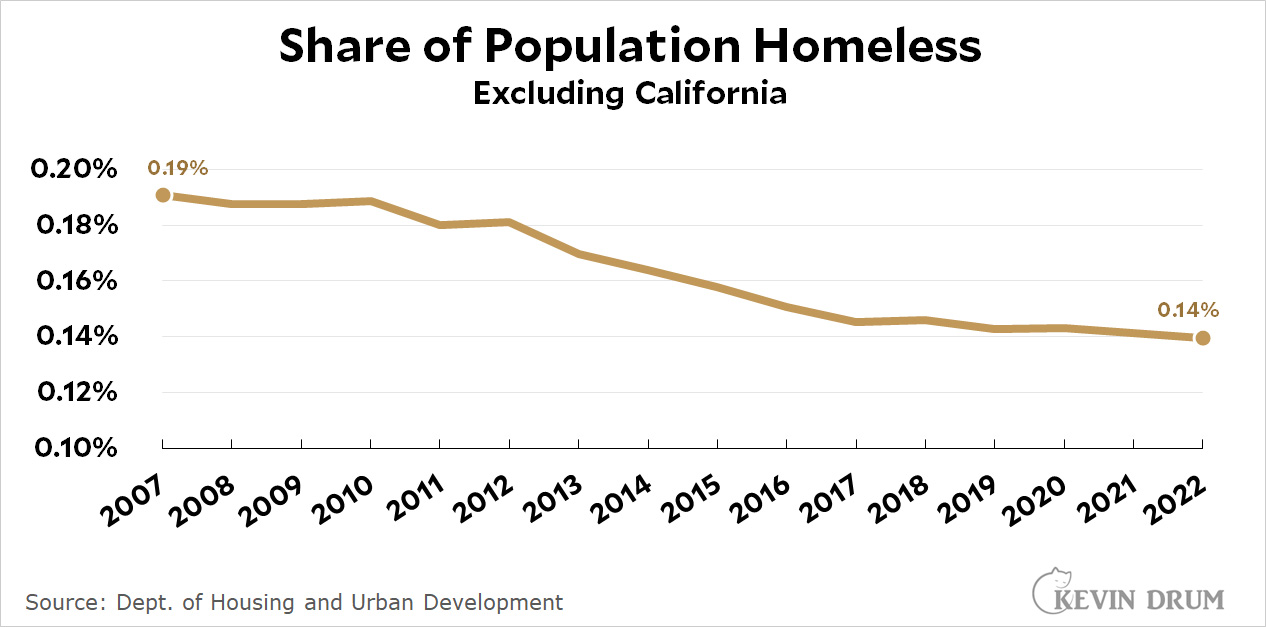

You'd never know it from media and activist reports, but homelessness has been a big policy success in 49 states. As usual, though, California is the great outlier when it comes to anything housing related.¹ Policy recommendations should always take that into account.

You'd never know it from media and activist reports, but homelessness has been a big policy success in 49 states. As usual, though, California is the great outlier when it comes to anything housing related.¹ Policy recommendations should always take that into account.