Yesterday I wrote about new regulations limiting sulphur content in the bunker fuel used by oceangoing vessels. I concluded that the effect on climate change of these limits was minuscule, but today Alex Tabarrok links to an article in Science that suggests the effect might have been more substantial.

But there are reasons for skepticism. On average, solar radiation amounts to about 1000 watts per square meter. According to a study quoted in the article, this compares to an increase of 0.1 w/m² due to the sulphur limits. That's not a lot.

The 1991 Pinatubo volcano, for example, reduced solar radiation by about 4 w/m², which led to a global temperature drop of 0.5°C. This suggests that a change of 0.1 w/m² would produce a global increase of about 0.012°C, a very small amount.¹

But what about the North Atlantic specifically, where ship traffic is heavy? The study estimates that the effect on solar radiation is about ten times stronger, which might lead to a sea temperature increase of 0.12°C—though this is probably an upper limit thanks to the inertia of ocean temps. This compares to a recorded increase of 0.91°C so far this year. In other words, the sulphur limits are responsible for at most one-eighth of the total warming.

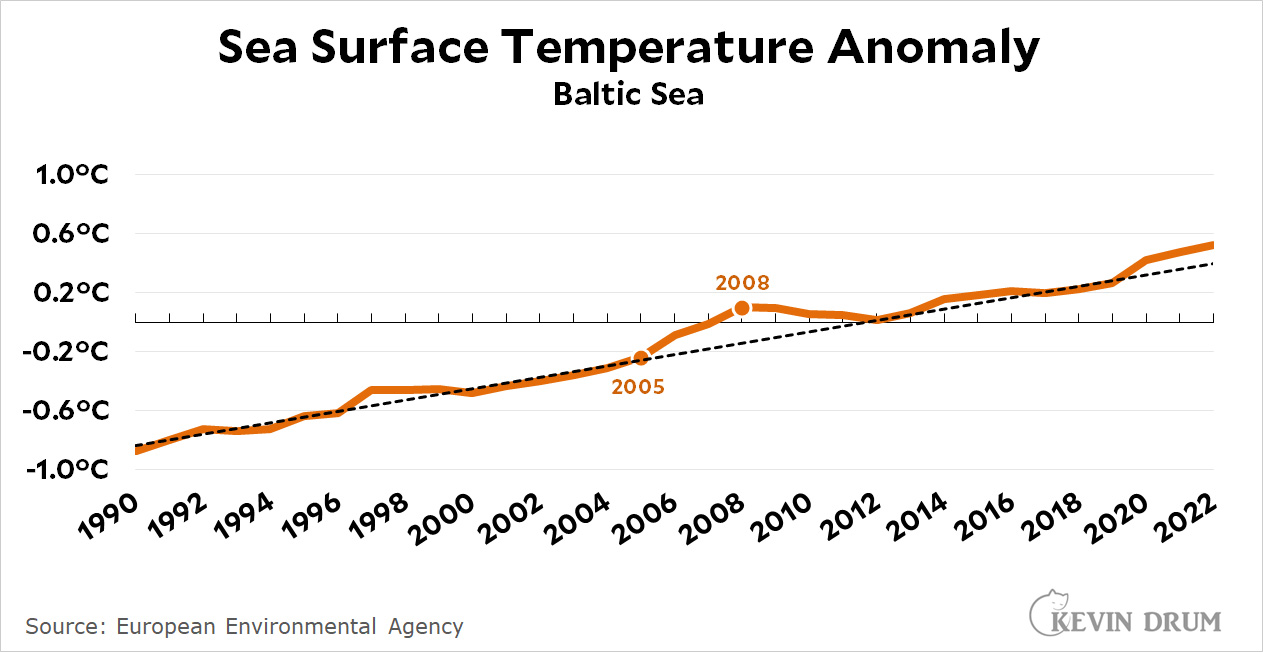

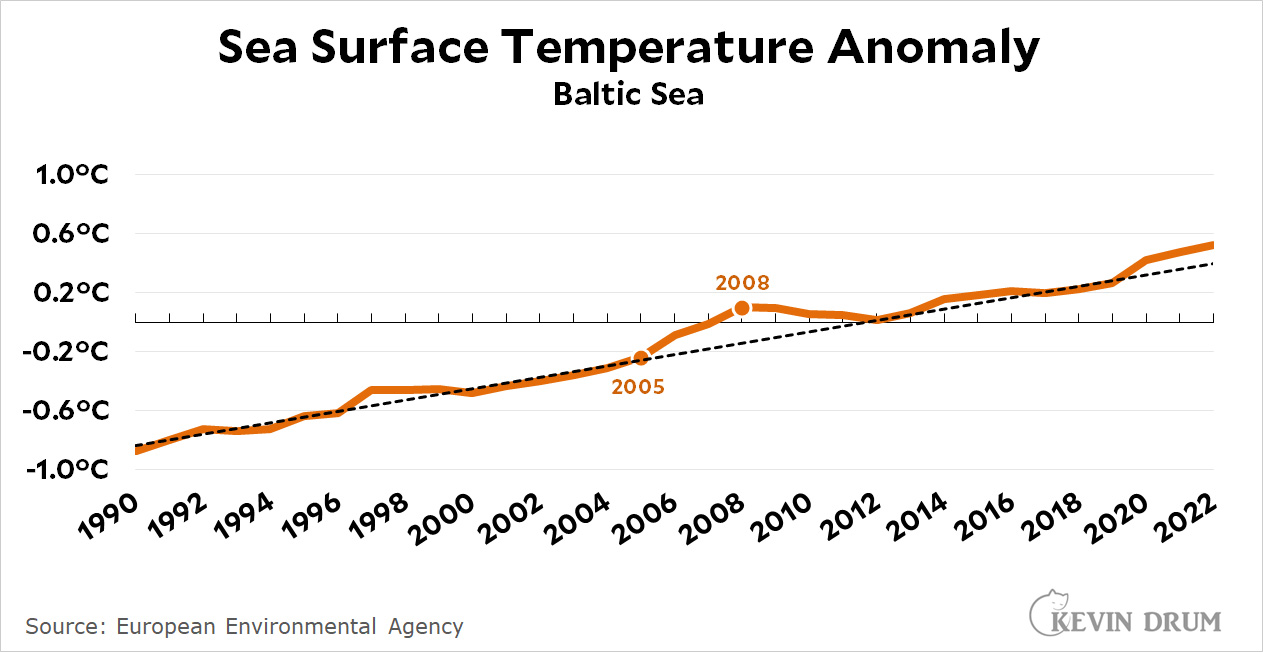

There are other reasons for skepticism. Certain regions of the world are designated as special Emission Control Areas. Sulphur content in these areas was limited to 1.5% in 2005. One such area is the Baltic Sea, but nothing happened there when the new limits took effect:

We're currently seeing a big sea temperature rise in the North Atlantic three years after new sulphur limits took effect, but if you take a look at 2008, which is three years after the ECA limits took effect, sea temperatures start to drop in the Baltic Sea. And in the 17 years since the limits started, Baltic temps have just followed their previous trendline.

We're currently seeing a big sea temperature rise in the North Atlantic three years after new sulphur limits took effect, but if you take a look at 2008, which is three years after the ECA limits took effect, sea temperatures start to drop in the Baltic Sea. And in the 17 years since the limits started, Baltic temps have just followed their previous trendline.

Put all this together and there's still little reason to think that the sulphur limits have had much effect on either global warming in general or on North Atlantic sea temperatures specifically. Without all the other factors in play,² it's unlikely we'd even notice anything different.

¹Yes, I'm assuming a linear response. I think that's safe at low levels.

²The eruption last year of an undersea volcano near Tonga; a strong El Niño this year; and an unusual lack of Saharan dust over the ocean.

It's true that spending on goods has been flat since mid-2021 while spending on services has continued to rise.¹ But trade is all about absolute numbers. Despite the difference in growth rates, spending on goods continues to be above its pre-pandemic trend while spending on services is below it. The big growth in spending on goods during the pandemic may have gone away, but it's come to rest at a very high level.

It's true that spending on goods has been flat since mid-2021 while spending on services has continued to rise.¹ But trade is all about absolute numbers. Despite the difference in growth rates, spending on goods continues to be above its pre-pandemic trend while spending on services is below it. The big growth in spending on goods during the pandemic may have gone away, but it's come to rest at a very high level.