What causes cavities? Lots of things, it turns out, but mainly sugar, just like you learned in grade school. However, sugar doesn't directly produce cavities. As with all things in biochemistry, the actual mechanism of cavity production is pretty complex.

But let's simplify. The main culprit in the conversion of sugar into cavities is a mouth bacteria called S. mutans. It does two things. First, it eats sucrose (table sugar) and produces a sticky biofilm that protects teeth. If you feed it enough sucrose this biofilm becomes quite thick and we call it plaque. Second, S. mutans binds to the sticky plaque and metabolizes any kind of sugar into lactic acid. If you provide enough sugar, S. mutans will produce more and more acid at its binding site. This acid eats away tooth enamel and creates cavities.

But let's simplify. The main culprit in the conversion of sugar into cavities is a mouth bacteria called S. mutans. It does two things. First, it eats sucrose (table sugar) and produces a sticky biofilm that protects teeth. If you feed it enough sucrose this biofilm becomes quite thick and we call it plaque. Second, S. mutans binds to the sticky plaque and metabolizes any kind of sugar into lactic acid. If you provide enough sugar, S. mutans will produce more and more acid at its binding site. This acid eats away tooth enamel and creates cavities.

Wasn't that interesting? But why the lesson? It's because I recently heard about a product that modifies S. mutans and prevents cavities. All it takes is a single swab and you're more or less cavity free for the rest of your life. So why don't we have access to this? According to a widely cited piece by Scott Alexander, it's because of blinkered government obstruction:

The FDA demanded a study of 100 subjects, all of whom had to be “age 18-30, with removable dentures, living alone and far from school zones”.... The FDA wouldn’t budge from requiring this impossible trial.

As near as I can tell, this isn't really true. Here's the story.

It starts 50 years ago with Jeffrey Hillman, a professor at the University of Florida. He began examining S. mutans to see if it could be modified so it didn't produce lactic acid. That turned out to be possible, but S. mutans didn't survive the process. So then he replaced the gene sequences that produced lactic acid with gene sequences from Mexican beer that produced alcohol. Bingo! He had a strain of S. mutans that created tiny amounts of alcohol, which is harmless to teeth.

But that's not all. Hillman's strain also produced an antibiotic that killed competing strains. Shortly after you apply the new strain, it kills off all the ordinary S. mutans and colonizes your mouth forever.

In 1996 Hillman started a company called Oragenics to commercialize his discovery, which he called SMaRT (S. Mutans Associated Replacement Therapy). But there was an obvious problem. It was the product of recombinant DNA, a true transgenic that combined the genes of two different species. Not only that, it was specifically designed to kill off the original strain. If it escaped, it had the potential to kill off ordinary S. mutans everywhere, with unknown consequences.

This is why the FDA moved so slowly. Finally, though, after several years of lab and animal trials, Hillman got permission in 2004 for a safety trial on humans. First, though, he was required to create a special strain that died unless it was fed a specific amino acid daily. That way, if it escaped it would die of its own accord.

This is why the first trial involved people with dentures. It wasn't to test cavity fighting, it was solely to find out if Hillman's strain was safe. If anything went wrong, denture wearers could just bleach their dentures and stop applying the special amino acid.

This was a tiny trial—the actual size is a little unclear, but it was somewhere between two and a dozen volunteers under age 55—and it was apparently a success. Three years later Hillman got permission to try his new strain on people with real teeth, though the volunteers would be required to spend a week in biocontainment.

This is where the story trickles to a stop. In 2011 Oragenics finally announced the new trial, but I can't find any evidence that it ever took place. It's not in the FDA's database and Oragenics never announced any results.

Why? In 2014 the CEO of Oragenics said they had shelved it due to "regulatory concerns and patent issues," without specifying what those were. But that's probably not the whole story. In the intervening years the S. mutans project had spun off some research lines that turned out to be more promising than the original cavity-fighting research. SMaRT was most likely abandoned simply because Oragenics had better things to do with its limited resources.

In any case, Oragenics secured a patent in 2016 and then did nothing more until last year, when it licensed its patent to a company called Lantern Bioworks. Lantern has a twofold strategy. First, they're selling SMaRT in Próspera, a libertarian charter city on an island off Honduras that allows consensual testing of just about anything. Second, they're hoping to reclassify SMaRT as a probiotic, which has a simpler approval process.

Does SMaRT work? As far as I can tell there's no clinical testing to prove it. But one thing I find telling is that I dredged up a couple of articles about the prospects of using oral bacteria to fight cavities. One was from 2012 and doesn't mention SMaRT at all even though Hillman is quoted. The other is a journal review from 2019 that mentions a bunch of different ways S. mutans could be targeted to reduce cavities, but conspicuously doesn't mention genetic engineering to eliminate lactic acid production.

So that's that. Hillman retired from Oragenics in 2012, presumably after the decision to focus on different projects. As for the fears of Hillman's strain escaping and causing havoc, I can't say. It sounds like a reasonable concern in general, but I have no idea whether the FDA went overboard. I guess we're going to find out.

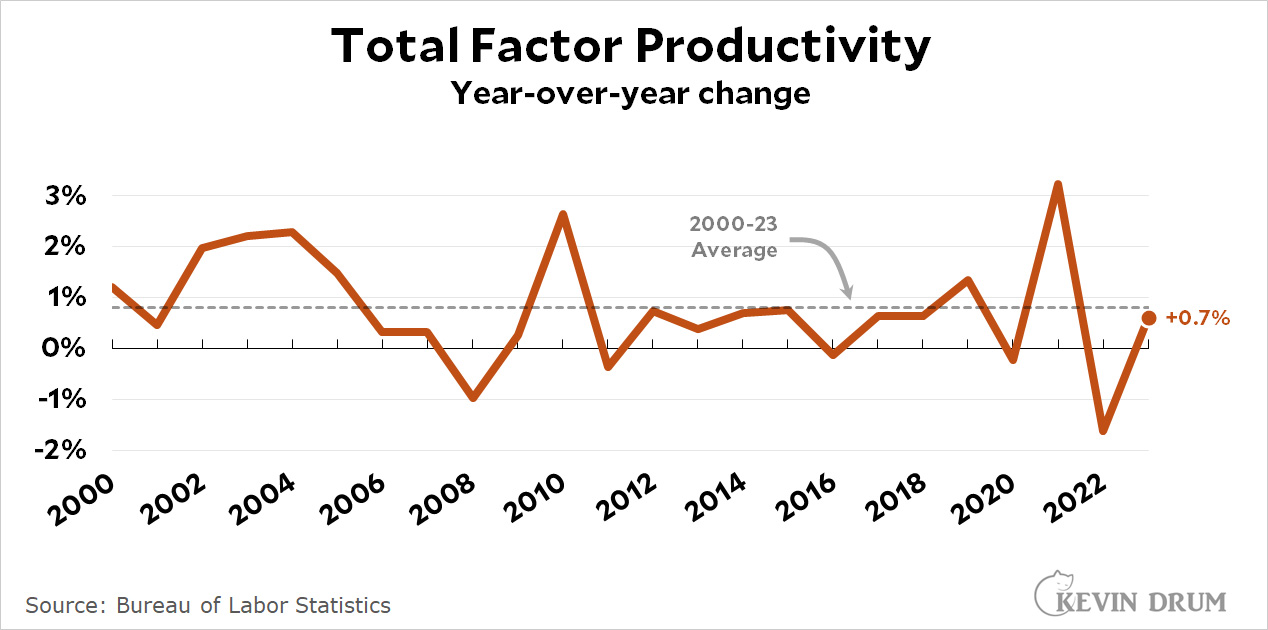

This is right at the average of the past five years and slightly below the average since 2000. In other words, kind of meh.

This is right at the average of the past five years and slightly below the average since 2000. In other words, kind of meh.