Marissa Evans writes about her 70-year-old father's death in January from COVID-19:

Since my father’s death, I have stared at the January 2022 calendar page attempting to trace his COVID-19 exposure and when he started coughing. I’ve tried reconstructing timelines and symptoms with dates, texts and calls to understand why my father died. But I know it will not make sense. The way we lose Black men in America never makes sense.

Loving a Black man in America often means your time with them will always seem short-lived....Black people are 2.5 times more likely to be hospitalized and 1.7 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than white people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

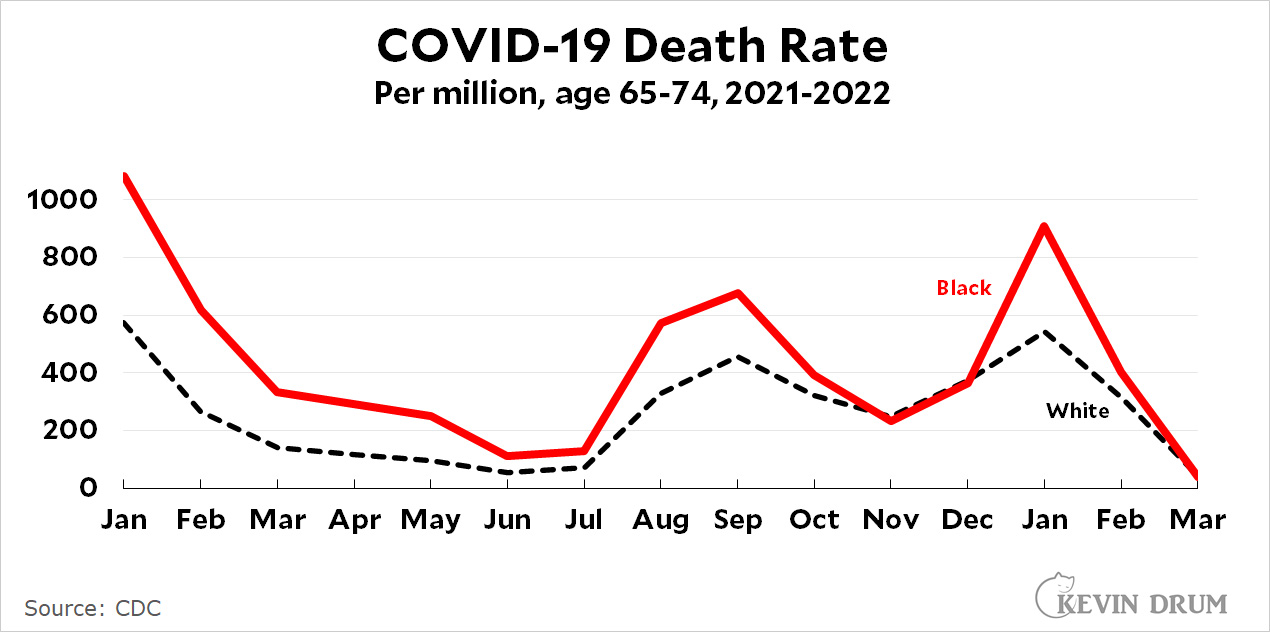

I don't want to reduce Evans's grief to statistics, but COVID death rates actually illuminate—or perhaps add to—her confusion:

There are two obvious things to say here. The first is that although it was once true that the Black community had a higher risk than the white community of dying from COVID, that risk started to plummet in October and has mostly matched the white death rate since then.

There are two obvious things to say here. The first is that although it was once true that the Black community had a higher risk than the white community of dying from COVID, that risk started to plummet in October and has mostly matched the white death rate since then.

But the second thing is that mostly is not always: There was a huge spike in the Black death rate in January—exactly the month that Evans's father died. This was true of all age groups, not just the elderly, and it was outsized compared to both the white and Hispanic death rates. This really doesn't make sense.

When I read pieces like this, which discuss the way Black patients are treated by the medical system, I almost always come away with conflicting responses. On the one hand, I get annoyed at the errors and hyperbole. Generally speaking, Black people aren't dying from COVID at higher rates than white people these days. That's outdated. The PNAS study Evans mentions later doesn't show that lots of white medical students hold outrageous racial beliefs. It shows that when they start school, white students average about 15% incorrect beliefs and this declines to 5% by the end of medical school. Finally, the litany of complaints about various unhappy interactions with doctors rarely strike me as unusual. Doctors periodically treat everyone badly, and most of the complaints feel very familiar to me.

On the other hand, both anecdotes and data really do support the notion that white doctors systemically treat Black patients worse than white patients. Some of this may be class bias more than racial bias, and some of the outcomes are due mostly to problems outside the health care system. (For example, Evans talks about life expectancy, but if you account for income something like 70-80% of the racial difference in life expectancy goes away.) Still, even with all that acknowledged, a racial component always remains. There's just no doubt that, one way or another, the mere fact of being Black leads to worse medical care on average.

Considering many of those whites are "jews" it further dilutes it. More likely blacks are more fatter and have vit d deficiency at a worse rate than whites. It's not a large over performance fwiw.

"More fatter" certainly describes your head.

Do not feed the troll.

Looking at the graph to me it shows that black death rates are higher at the peaks of covid surges, and match white rates at the lulls between the surges. But I can't come up with a "just so" story to explain it.

I noticed that and it says to me that, when the healthcare system is at peak stress, black people are disproportionately among those affected at the margins. There is no chart for uninsured or poverty. but we know black Americans are disproportionately represented in the uninsured and poor, so that could also explain a good bit of the difference.

Her father was boosted, but black men are also relatively low in vaccination rates, I think.

Excellent observation. I was about to make the same suggestion.

This bears further research but would be explanatory for the basic behavior.

The spike in January can make sense if it were all BA.2, or similar variant, that's become more prevalent among black people.

Black death rates during spikes might be explained by the hospitals serving poor Black areas tend to be public hospitals that are underfunded and more overwhelmed during surges in hospitalizations. This was true in the NYC area.

Many statistics need to be examined on a more localized level to tease out what is really going on.

Black maternal deaths are consistently at a higher level than white. Some of this can be addressed by changes in hospital practices--checklists, etc.

That was my thought, during spikes is when the health care system is most taxxed and so the people with the worst access to it to begin with will be the ones who suffer the most.

"Findings suggest that when Black newborns are cared for by Black physicians, the mortality penalty they suffer, as compared with White infants, is halved."

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1913405117

Relevant b/c since they're newborns, no patient behaviour could possibly be implicated.

The chart axis is a bit misleading as the graph will always make it appear that the gap shrinks when the death rate is lower.

The disparity in death rates in March, April and May 2021 is larger than many other months even though the space between the lines is smaller. Hard to tell if the disparity actually improved in March 2022...and obviously we are still weeks away from actually knowing who died in March.

Hard to draw any conclusions from a bad graph.

Anecdotally, the only pregnant women still unvaccinated in my liberal area (Berkeley) are Black. The first patients vaccinated in 2021 were wealthy white women who aggressively pursued appointments. There was some reluctance among Hispanic women which seems to have waned with the Delta variant. Now our white patients are vaxxed x 3 and Hispanic patients vaxxed last fall with some starting to get their 6 month boosters. The only patients still getting seriously ill from Covid are Black. If the trend to decline the vaccine extends to older Black Americans, that would explain the death rate.

I find it interesting that mistrust in the advice of personal doctor or public health recommendations by Black Americans is seen as the fault of the health care system, but mistrust by political Covid anti-vaxxers is seen as the fault of Fox and Q-anon, and mistrust by organic, gluten-free, yoga practicers or faith-based practicers is the fault of their informational bubble. Of course none of this is the seen as the fault of the individual who is freely making the choices.

"Of course none of this is the seen as the fault of the individual who is freely making the choices."

It depends on what you're trying to do. If you are trying to craft public policy to reduce death and suffering, it makes sense to focus on what external causes are nudging a population's behavior this way or that way. If you are trying to be a moralizing scold who washes their hands of others' misfortune, then yeah, concluding that those people made their choices and got what they deserved is probably going to work for you.

Lol, what a comment. Given the lack of actual pedophile, kidnapping rings in the Democratic party, the comparison to actual medical malpractice appears.....ridiculous?

But thats what internet comments are for, right?

Slight correction: black deaths are twice as high as white deaths is not so much "old news" and it is a function of the outbreak. Higher hospitalization rates, higher difference in death rates. I don't know that's a function of resource allocation.

The "urban renewal" of the 60's devastated many black communities, including loss of investment in housing, so families could not build up generational wealth.

The "war on drugs" was mainly designed to criminalize Democratic constituencies, i.e. Blacks and Hispanics (and the poor). Also a great way to destroy communities.

Correcting for various conditions to tease out the role racism may play is a bit disingenuous when racism exacerbated those conditions to begin with. Sort of like correcting the effects of masking on Covid spread by levels of community spread--a bit circular.

Not just them, but also Appy whites who after the New Deal, voted Dem. It ain't all black and white bub.

I can't believe we're still guessing - hasn't anyone done any solid research? There are a bunch of different variables that all might play a part. Another variable not mentioned is the ability to avoid the epidemic by avoiding contagion. I assume the per million is per person not per case. Included in that variable would be household size, working status, kind of job, etc. Some of that would be absorbed in an income variable. Not buying that you can make a grand statement without digging deeper.

Nothing is ever their own damn fault. ????

Seems to me that class bias as opposed to bias against Blacks is pretty well nullified by the insurance system we have. Lower class patients will not have the same choice of doctors that upper economic class patients have whatever the color of their skin. The best doctors can choose what insurance carriers they accept and therefore can predict what class of patient they will accept.

The Black death rate from COVID-19 doesn’t entirely make sense

Note for members of Know-Nothing persuasion:

The "Black death rate" and the "Black Death rate" are two different things.

Thank you.

But that's exactly what I thought when I glanced at the headline! What, bubonic plague is making a comeback, how did I miss that?

My first read was the same.

Another point of confusion. The “Black death rate” refers to deaths of Black people. The “Black Death rate” refers mostly to deaths of white people.

Fair to say, if the Black Death happened today, it would get a different name. (The term predates the bubonic plague pandemic of the 1300s, going back at least as far as Homer.)

"... There's just no doubt that, one way or another, the mere fact of being Black leads to worse medical care on average."

Of course there is doubt. Hispanics live longer than whites. Is that because whites receive worse medical care?

How big a factor is state government? Black Americans are not evenly distributed across the country.

I dunno,

That seems like a stretch looking at your chart. That spike in Jan is eye-popping. It's about double the white rate.

There are diseases, such as Lupus, which disproportionately affect Blacks. In the past, deaths from disseminated Valley Fever (coccidioidomycosis) have been noted to be increased in certain racial groups, including Blacks. In no way do I want to diminish the existence of unequal care, lack of access, lack of trust, etc. that affects Black patient outcomes. But as a physician, I do have to wonder whether underlying immunological differences (aside from age, known co-morbidities or immunosuppression) are present in some populations - perhaps sub-populations of some whites, Blacks, or other groups. We don't know, and it is worth knowing.

I'm not sure I understand your reading of this graph. It appears that during both of the last two peaks, black death rates were about 1/3 higher than white death rates, with death rates approaching each during the intervals during peaks.

This would be entirely consistent with deaths during cycle peaks being driven by, for example, demographic cycles where a new wave of COVID-19 sweeps through more vulnerable populations before burning out in those pops and spreading to less vulnerable ones. Then we would expect the largest differences in death rates during peaks.

I think the issue here is treating "black" and "white" as homogenous populations that an epidemic will spread equally within, rather than populations with their own structure, where vulnerable black populations may be substantially more vulnerable than white populations.

For context: I'm a population ecologist with experience modelling cyclic populations (although not epidemics specifically). It would not be surprising to see different magnitudes of peaks and troughs in distinct subpopulations, nor is it surprising to see the gap in rates narrow during troughs. It would be surprising if the gap didn't widen again when the next cycle occurred.

And yet Mrs. Thomas's husband will be just fine.