This doesn't really make much sense:

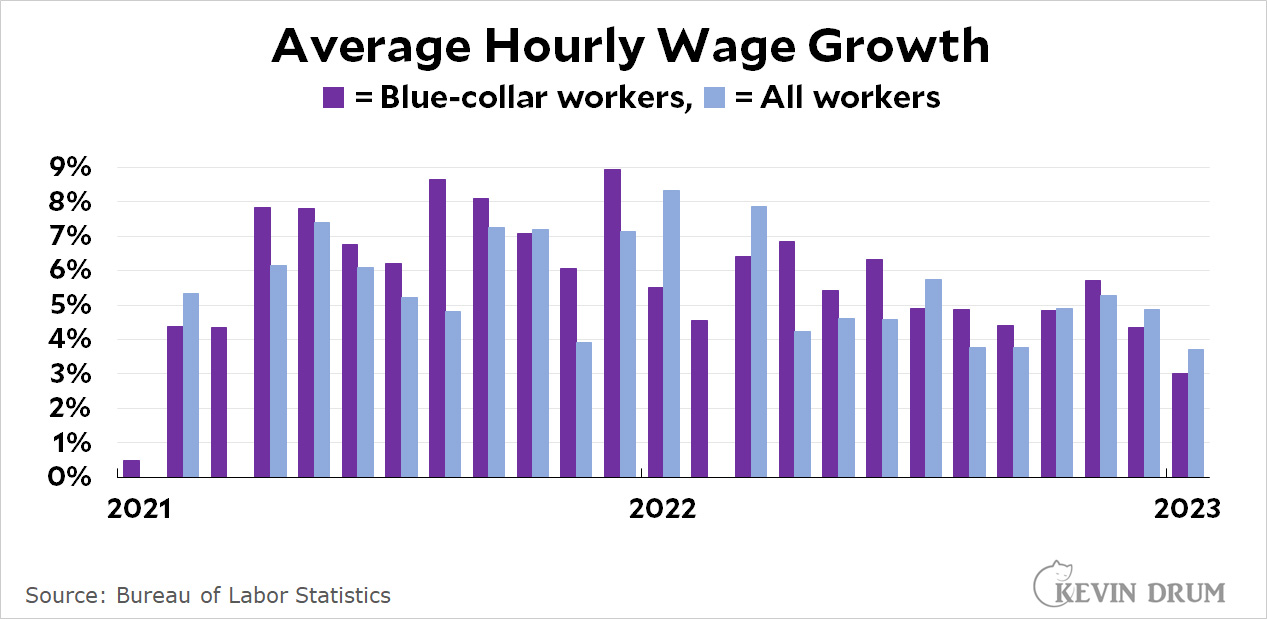

January came in with slower wage growth than in December. But if we added a gazillion jobs and sent the unemployment rate even lower, why did wage growth slow? In theory, workers have more leverage and should be demanding higher wages.

January came in with slower wage growth than in December. But if we added a gazillion jobs and sent the unemployment rate even lower, why did wage growth slow? In theory, workers have more leverage and should be demanding higher wages.

Theory seems to have a real problem at the moment. Or maybe the explanation lies here:

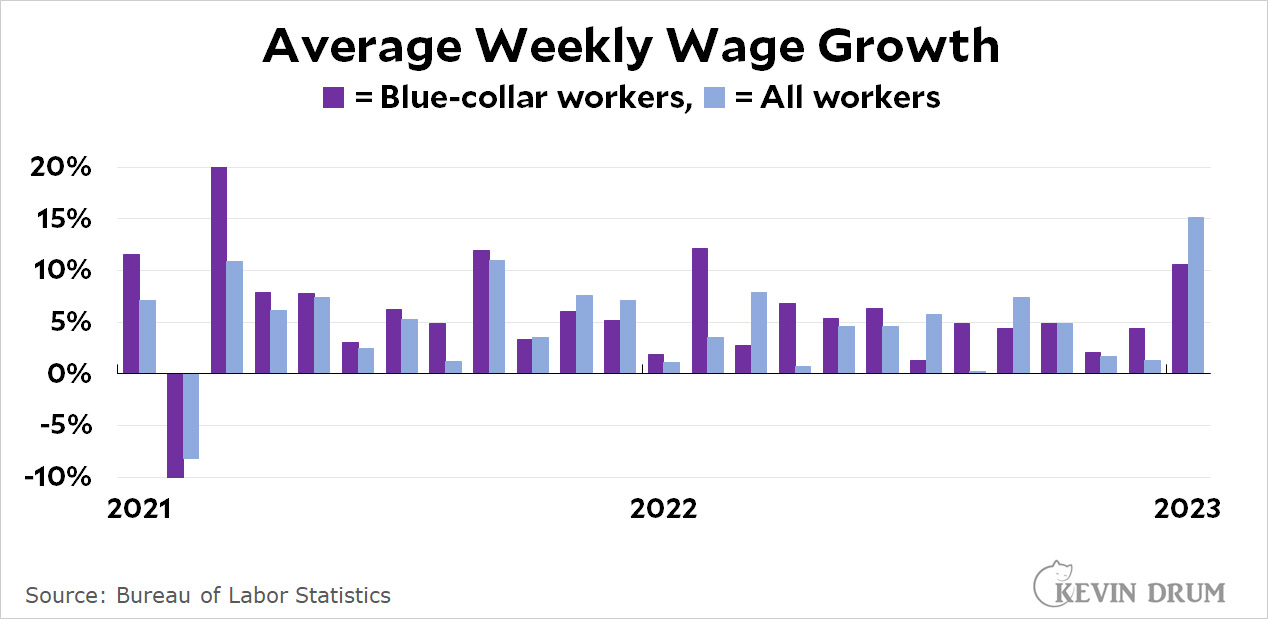

Employers aren't raising hourly rates much, but they are increasing the number of hours of work. As you can see, this means that weekly wages jumped considerably.

Employers aren't raising hourly rates much, but they are increasing the number of hours of work. As you can see, this means that weekly wages jumped considerably.

I have no idea how theory accounts for this. I will await commentary from economists, though I don't expect they'll provide any kind of consensus. They never do these days.

POSTSCRIPT: These numbers are not adjusted for inflation. We don't have inflation numbers for January yet, and the wage growth rate is very, very sensitive to even small changes in the inflation rate. In normal times I could plug in an estimate and probably be pretty close, but these aren't normal times.

That's because the theory that workers have anything more than nominal power over their wages is dead wrong.

The only workers who have leverage over their wages are workers already earning higher wages. Those at the lower end of the wage spectrum have essentially zero leverage.

Yeah this is hilarious. Perfect example of economic theory being divorced from reality. Plus, it’s not like wages didn’t go up, they just didn’t go up as much.

Although Keynes said that workers may not be very resistant to decline in real wages through inflation (as opposed to cuts in nominal wages, which rarely happens anymore), in fact there is response of wages to inflation. So when inflation did drop down in July 2022, some upward pressure on wages decreased.

But these numbers are tricky. There are different measures of wages/salaries, (specifically the establishment and household surveys) which sometimes differ significantly as Kevin has pointed out before. Numbers are often considerably revised. Again, just because some agency comes out with monthly numbers doesn't mean that the monthly differences are very significant.

Start making more money weekly. This is valuable part time work for everyone. The best part ,work from the comfort of your house and get paid from $10k-$20k each week . Start today and have your first cash at the end of this week. Visit this article

for more details.. https://createmaxwealth.blogspot.com

If economists were judged by the same standards as bridge engineers, there'd be a lot fewer of them.

Instead, we hear a lot of "No one could have known how this would turn out."

We also get lots and lots of their pet theories which endorse their pet views, which have much more to do with their biases than with reality.

That's not entirely fair. Predicting with any accuracy the behavior of extraordinarily complex systems is really, really hard. Macroeconomics is in some ways like weather forecasting--it bumps up against data and calculation constraints and lacks any real way to conduct repeatable experiments, so it's not suprising it's often wrong in the short term and significantly wrong in the medium term.

By contrast, buiding bridges is easy, as the strength of materials and the principles of engineering them don't depend in nonlinear ways on countless external factors upon which you don't or can't have data. (You can also pretty readily test whether or not a bridge will work) Which is great--it means that we can have thousands upon thousands of reliably useful bridges.

But criticizing economists for failing to live up to the concrete successes of bridge engineers is like criticizing oncologists for failing to have the predictive certainty of, like, a life insurance adjuster. Whatever the skills and aptitudes of the people involved, one endeavor is just a lot harder to accomplish than another.

The theory of subjectivation to capitalist authority receives more evidence.

More than half of US workers are employed by a firm of >500 employees and for all but the most educated their bargaining power is practically nonexistent.

BLS says that more than 55% are employed at firms smaller than 500 employees. https://www.bls.gov/bdm/sizeclassqanda.htm

But, whatever the percentage companies seem to be brutally focused on fighting wage increases, especially higher paid employees. Instead they are offering more entry level pay in order to fill those jobs. Witness tech companies firing top employees with lots of experience.

The principle of "last hired, first fired" has a perverse effect on average wages. During hard times when lots of people are being laid off, it's the most junior, meaning lower paid, workers that are laid off first. Because the remaining work force consists of the more senior and so higher paid workers, mass layoffs increase the average wage paid to the people who are still working. The flip side of that coin says that when payrolls are expanding, the new hires come in at the bottom of the pay scale, thereby driving the average wage down.

the monthly data looks to be highly variable. It seems unlikely that monthly job increases are directly tied that months wage increases.

Hiring often takes a lot of time. Wages are often only adjusted as part of a regular schedule.