I came across an old Bloomberg story today that points out something interesting:

A measure of US profit margins has reached its widest since 1950, suggesting that the prices charged by businesses are outpacing their increased costs for production and labor. After-tax profits as a share of gross value added for non-financial corporations....

Wait a second. What's this "after-tax profits as a share of gross value added" business?

In a word, it's a measure of markup, the amount a company charges for its products above and beyond the cost of raw materials and labor. For example, if I can make a widget for $100 and sell it for an average of $150, my markup is 50%. If I raise the price to $160, my markup is 60%.

Unless you can reduce the cost of manufacturing—by buying cheaper parts or paying workers less, which is unlikely these days—the only way to increase your markup is by increasing your selling price. So how about if we take a look at that over time?

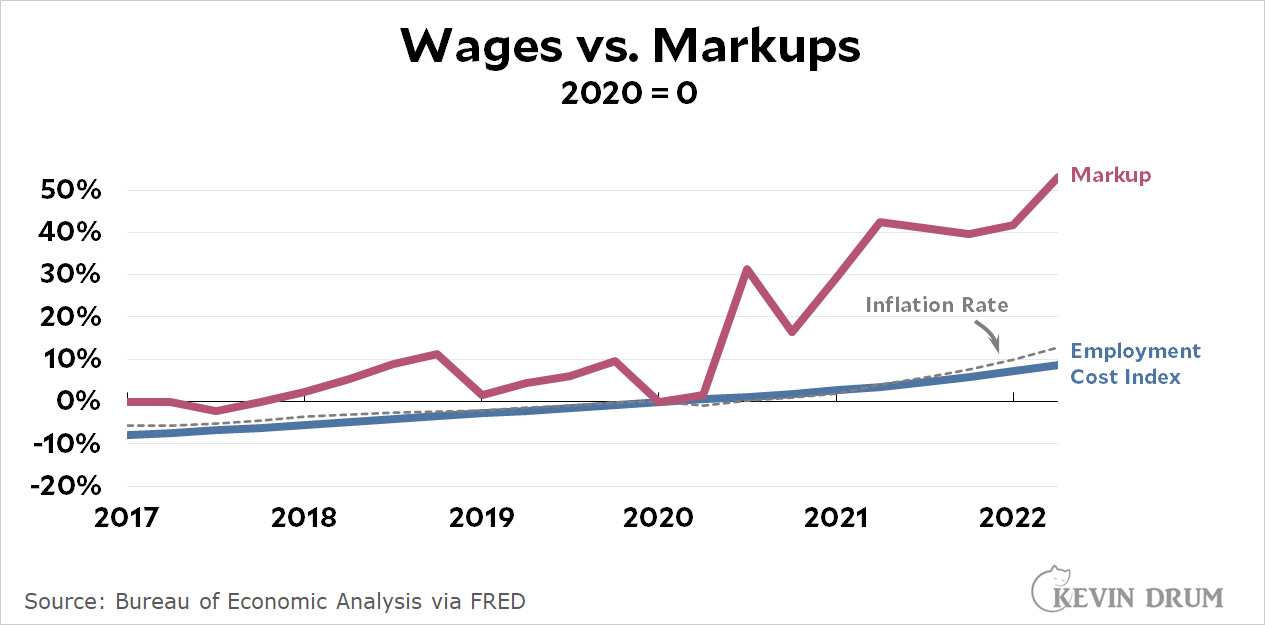

First, take a look at the blue line: it represents the total cost of employing somebody, including wages and benefits. Since 2020 it's risen at less than the rate of inflation.

First, take a look at the blue line: it represents the total cost of employing somebody, including wages and benefits. Since 2020 it's risen at less than the rate of inflation.

Now look at the red line: it represents after-tax profits as a share of gross value added, aka markup. Before 2020 it rose roughly in line with inflation, but since 2020 it's skyrocketed by more than half (you can see the underlying numbers here).

Corporations are increasing prices with abandon and blaming it on inflation. But it's not because of inflation. It's a cause of inflation. Prices are rising not because of workers, whose income is going up more slowly than inflation, and not only because raw materials are more expensive. It's mainly because companies are raising prices above and beyond that for no special reason except that they can. And all of us are paying the price.

There seems to be a lot of confusion in your math / graph. It may be just bad wording.

1. We expect Markup to increase with inflation, but Markup _Percentage_ to stay roughly constant. If a widget cost $9 to make and sold for $10 and the value of the dollar dropped 50% then the widget would cost $18 to make and sell for $20. Markup doubles, Markup Percentage stays at 10% or 11.1% depending on whether it is calculated based on costs or sales price.

2. "Profit" is a sloppy word. Do you mean net profit? Gross profit? Another measure of margin?

3. As you add more capital and tech requirements into the labor mix and as compamies adapted to COVID I would expect more management complexity and more overhead costs that do not get counted as COGS. If so, then we would expect GP% to increase as companies increase prices to cover those costs. Nothing wrong with that.

4. Don't you find it strange that companies can raise prices? Why would a corner pizza shop be able to raise prices rather than have a new entrant come in and undercut it? Obviously, there must be additional costs (ie. regulatory compliance, crime, etc.) that are not being measured when you calculate costs in your overhead measure.

5. I have always wondered why people expect wages to increase with productivity. That certainly makes sense if labor is adding more value - if you have more educated workers, for example. But if unskilled labor becomes more productive that is presumably due to better tech, more capital investment, better management - the unskilled labor has not changed. Wouldn't you expect most of the increased value from that increased productivity to go to the sources of the increased productivity and not to unskilled laborers?

I'm not an economist, but your points raise a few questions for me. Re #3, if firms incurred greater overhead and management costs to deal with covid, which as you say would not affect the factor cost of producing things, wouldn't they be accounted for in the "after-tax profits" part of "after-tax profits as a share of gross value added"? The profit/value added ratio seems like it might be a standard Commerce Department measure which doesn't appear to be calculated for individual product lines but for all non-financial firms.

Re #4, what happens if, instead of looking to the corner mom & pop pizza shop for our thought experiment, we think about, say, Procter & Gamble, or 3M, or Georgia-Pacific, firms with real pricing power?

Re #5, I can only say that I'm old enough to remember the Cold War years, when a question like this would only have been whispered quietly in a back room among trusted friends. But alas, in those days it was massively important that we in the free world needed to prove to everybody else that our system would produce a better standard of living for ordinary people than the Commies could. The idea of "better" in those days of course included "rising." There are times when people can feel nostalgic for the Cold War.

Shilling for Capital.

🙂

re: 4

No, I do not find it strange that companies can raise prices, but I also do not think a corner pizza shop represents our economy and the sheer scale of investment needed to construct new factories or new networks which act as a barrier to entry by would-be competitors

But what do the CEOs of major companies say?

Michael McGarry, CEO of PPG, in response to a question whether prices will go back down now input prices are lower: "[W]e’re not going to be giving this pricing back....So we’re telling people, this is the new price. And if you don’t like it, please don’t place purchase orders."

William C. Rhodes, CEO of Autozone: "It is also notable that following periods of higher inflation, our industry has historically not reduced pricing to reflect lower ultimate cost."

Jim Snee, CEO of Hormel: "[O]ur Grocery Products pricing is very sticky and so the pricing that we’ve taken and that we’re in the midst of executing the additional price increase, that pricing will will by and large to stay."

I operate on the assumption that any quote or factual claim without a link to a source is fictional

Given the lack of basic knowledge you display in your posts, I operate on the assumption that the weight of your opinions is negligible. Sorry, just being honest, albeit brutally so.

Oh, absolutely-- imaginary hypotheticals are where it's at

All from recent earnings call transcripts...

PPG Industries (PPG) Q1 2022

AutoZone, Inc. (AZO) Q3 2022

Hormel Foods Corporation (HRL) Q4 2021

These are only a few of many similar statements by other companies' CEOs.

Since MF doesn't know how to use Google, I decided to look up one of quotes for him. Specifically, the William C. Rhodes, CEO of Autozone quote. Took less than 30 seconds to verify. But why make an effort when it's so much more satisatisfying to throw shade, amirite?

And from the same source, Autozone’s CFO:

“And as I’ve said before, inflation has been a little bit of our friend in terms of what we see in terms of retail pricing.”

Oh yeah. I Despise this one. He's a libertanian troll who hasn't updated his playbook in thirty years. And, of course, operating in massive bad faith. Thank you, David Friedman, for introducing me to this type of tosser all those years ago on Usenet.

In re #5: Never heard of Baumol's Cost Disease, I see. Are you sure you're qualified to post in that tone of voice?

Never heard of ‘efficiency wage’ either, apparently.

IOW, just another libertaian troll. He's pulled this kind of stunt before. Including the "You didn't say your words right' ploy.

Because many people aren't scum.

Labor that is more productive is by definition adding more value.

Yes, it has. It's become more productive, and as such is entitled to more remuneration.

The source of that increased productivity remains the worker. Unless management is prepared to get at the coal face themselves, all they've done is facilitate that. If you give someone a pickaxe, saying "that pickaxe is what lets you dig faster; YOU haven't changed, you just have a better tool. I provided the tool, so I get the gains" then the response of that person should be to drive that pickaxe through your skull.

Well put

The tool itself cannot create additional value; the tool does transform the value of the labor.

Re 3.: I don’t think the effect of COVID on business costs is obvious - some costs would have gone down as WFH increased.

Re 4.: The incentives structure for management of many large businesses favors profitability over market share.

Re 5.: If you’re producing luxuries, this maybe works. If you are selling into a mass market, you may well want your customers to have money to spend. Henry Ford figured this out a century ago.

The costs of opening a new pizza place mainly involve dealing with large chains with that have access to more capital and can undercut you for long enough to force you out of the market. If they are kindly sorts, they might offer to buy you out, but that's unlikely for a pizza place. That's why we only have a handful of companies in every line of business.

There was a podcast, I think Planet Money, where they had an economist on who had called into loads of corporate earning calls. They were telling their shareholders, straight-up, that they were using the pandemic to jack up prices and increase profits.

The figures certainly support the claim that inflation is at least partly due to government pandemic handouts creating a too-much-money-chasing-too-few-goods scenario. If firms believed increased consumer demand was only temporary, it would have been rational to exploit the situation by raising prices instead of increasing production. It would also have deterred new competitors from entering a market whose buoyancy was going to be short-lived. If that's the case, markups should soon return to a more typical level. Exceptions might be products like oil and grains, where a global shortage coupled with an inelastic demand curve will keep allowing companies to keep prices high and reap super-profits.

Why would any company spend money to increase production and put their profit margin at risk?

Market concentration means limited competition.

No it doesn't, what it shows is that we don't have anything even remotely resembling "free markets" in the US. Producers are able to simply charge whatever they think is the profit maximizing price because competition is virtually nonexistent in many markets. When one of the major producers raises prices, the other 1 or 2 firms in the market instead of using that as an opportunity to grab market share see it as an opportunity to raise their own prices.

Why would a company lower its markup? If the new higher price holds, they can make more by selling less. Good luck if you actually need the product.

I think the correct response to this is "NO S***". For some reason I don't swear here...

Anyways, isn't this kind of obvious? A $4 product suddenly costs $5 and inflation is 10% (so easy math), it should be $4.40 all things being equal. And when was the last time you bought something on sale in a supermarket?

Like I said, it's obvious.

If you say 'shite' instead of the shorter version your comment will pass without comment in most moderated platforms.

He's defining markup as "after tax profits as percent of value add", not as return on investment (ROI). But that will show basically the same thing--profit margins are going up. I don't think this applies to mom and pop shops and local stores.

Of course Robert Reich has been saying this for a while now.

Hard to do much analysis without more details. Do these markup figures include all firms? What's the difference between primary producers and retailers? What about the B2B sector vs. B2C sector? How about services vs. goods?

Blah blah blah. Corporate profits are up, what more do you need to know? They keep prices elevated because they can, not because they have to.

Uh, I'd like to know why they're able to do it now, and the details I mention might be helpful in getting that answer. Firms, after all, will clearly always try to get the highest price they can (consistent with business goals), right? So, why, if Kevin's chart is to be believed, are these corporations apparently better able to price gouge than they were previously?

My guess, brazenness. While they probably have always wished they could jack up the price to some exorbitant amount, they had a sort "it would be great, but we could never get away with something like that" moment, recognizing that doing so would cost them in the long run either via the consumers abandoning them in droves, or the government stepping in with some regulation or penalty. There was also probably some degree of "this isn't right" human decency factoring in.

However having realized that the first thing isn't likely to happen (even less so in industries where companies operate like a quasi monopoly); the second would be extremely rare or close to impossible to happen even with Democrats in charge; and since Trump crashed the political scene, close to half the people in the US (especially those with money and power) no longer giving a damn about the 3rd concern, they finally decided to say "F' it" let's just jack up the price regardless of the actual costs.

That's a real chin scratcher, but I'll venture a wild guess that it is lack of concentration in far too many industries.

And, yes, that is sarcasm, because no shite Sherlock.

It occurs to me that the recent proliferation of loyalty programs among B2C businesses is an indication of a bias toward customer retention vs. new-customer acquisition. You don’t increase market share without adding new customers, so if your management compensation encourages raising profits, you have to get those from existing customers.

Monopoly power. Most lines of business have only a handful of players and they work in concert. Even apartment rental is apparently controlled by a central planning mechanism much like the infamous Gary dinners where steel makers set their prices.

The costs of entering a business are extremely high, and the existing players have the money to buy you out if that is the simplest course or otherwise undercutting and isolating you even if it costs them a little. Then, there's the matter of access to credit or venture capital which is available only to a very limited group.

Economists tend not to talk about economic power, but it is the main driving structural force.

Not if they want to remain employed they don't 😉 That's mostly snark, of course. That it's not entirely snark is disgraceful.

Wage -> price spiral?

Disaster, what will stop this runaway economy wrecker?

Increasing profit margins -> price spiral?

Healthy!

I’ve said this here before, but again, no sh;t! I’m no economist, but it seems absurd to me to expect companies to lower their prices just because their costs went down, assuming people are still paying the elevated prices.

what ever the market will bear, baby!

If people stop buying, or switch what they buy, then maybe prices drop. For something like oil, if prices get too high, it might trigger a recession that leads to a large drop in demand, and prices.

That's why modest inflation is a bigger problem than its relatively small amount would leave you to believe. It allows companies to jack up prices even more, and often get away with it because people feel the rise in price is part of the trend.

That's why we shouldn't be sanguine - as Kevin was all 2021 - about "just a little" and "only transitory" inflation. Such inflation demands a sharp response, even if it is more medicine than the patient needs.

This is pretty much the definition of inflation.

With more money to throw around, companies charge more for their products. That companies are charging more for their products today than current inflation shows, indicates that near-future inflation numbers will also be increasing.

And yes it's ugly. "We have a responsibility to our shareholders..." doesn't excuse it either.

Proper fiscal policy would have kept us from falling into this mess. But now that we're in this mess, I don't know what to do about it other than what the Fed has already done (which, I must admit, may have been too much, but we can't be sure due to the feedback delays inherent to the system).

We were in this mess before COVID. Prices were rising because of a lack of competition. There was too much central planning and collectivist action. COVID just made a lot of obvious trends obvious.

My only comment is another way of saying something I've said before. In this case, the way I'm saying is ... one of these things is not like the other.

Thing #1: The foundational principle that Adam Smith applied in establishing the capitalist method is sympathy, which he described in "The Theory of Moral Sentiments" (1759) by saying that it "operated through a logic of mirroring, in which a spectator imaginatively reconstructs the experience of the person he watches."

Thing #2: So in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you, for this sums up the Law and the Prophets (Matthew 7:12 NIV).

Thing #3: The foundational principle that Milton Friedman applied in establishing the unfettered free market method, which he described in "Capitalism and Freedom" (1962) by saying that the "doctrine of ‘social responsibility’, that (people that control) corporations should care about the community and not just profit, is highly subversive to the capitalist system and can only lead toward totalitarianism." Does that mean Putin is a capitalist?

I've heard a number of Republicans imply a belief that capitalism is divinely inspired. I express this idea because I think they're on to something that should reveal to them that they've lost their way. Or maybe it's me and I just can't see it, which is the other reason why I'm expressing this idea.

The following is to address my hindsight-based suspicion that my previous comment is being perceived as having little to no relationship with Kevin's post.

Whatever else is going on, there was a stable process that, since 2020, is no longer stable. The implied interpretation is that greed was stable till then and became unstable at that point. The alternate interpretation is that nothing changed. If someone makes any assumption about any subject, and looks exclusively for evidence to support their assumption, they'll find it.

That doesn't mean that the implied interpretation is correct, but it's not the only thing that's happened since 2020 that might be convincing people that it's winner take all, the more the better, and the faster the better, as if the whole of recorded history hasn't debunked that theory enough times.

Yes, Putin is a capitalist at the extreme end of the scale. Fascists and other authoritarians usually are. Yes, feudalism is a form of capitalism too. It's only when one has an active democratic government fighting collusion and the power of incumbency that we get something like Adam Smith's vision.

Thank you for including the source link in your wording update. Following it shows it is far more interesting to take it back much further and see the progression over the last seventy years rather than just the last five: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=VtLa

Thanks for pointing to that part of the graphic; it's easy to miss or misinterpret.

It is kinda notable that the clear upward trend in after-tax profits per unit of value added started right around 1973. Last year a Bruce Bartlett article wrote about the importance of the demise of international capital-flow restrictions after Nixon killed the Bretton Woods system in 1971. Wonder if that could have anything to do with this trend.

I think it has everything to do with that trend.

Me too! Man, I need a sarcasm tag . . .

Man, I "felt" it but didn't really look at many other numbers besides just raw profits - but corporations really kicked profit-milking into high gear after 2008. That actually shows something of a pattern, after 1973ish (incidentally, when we moved away from the gold standard - and no, I don't think that was a bad idea or the cause but it does seem like it allowed for capital to really screw everybody else by several more orders of magnitude...):

1. Profits go up at a slightly higher trend line than previous trend, then start to fall

2. Recession occurs (perhaps because the economy writ large can't afford the higher prices anymore)

3. Presumed anti-recession measures to juice demand again (measures that favor capital while throwing a bone to everybody else)

4. Return to 1, but at an even higher-sloped trend line for profit per unit of real gross value

I guess the question is, what major consumer goods or food company will be the first to decide that the moment is ripe to sacrifice some profits and lower prices to capture more market share. An old "we're lowering prices 20% to help regular Americans like you!" ad campaign could be really effective right now.

If the demand is elastic, they will do it, where the increased sales offset the lower margin.

And didn't most of us know this all along....

I don't think the Fed did. Unless jacking up rates is some Illuminati plan to get the GOP back in power.

More likely it's just the Fed-brains applying the wrong lesson, learned from previous crises, to the current problem. When all you have is a hammer...

Jacking up interest rate should help…

I guess I don't understand here. If demand for a product rises, then the price goes up until supply can catch up with the demand, and that change in price is the markup.

When we correctly pumped money into the economy, it increased demand, as seen by the uptick in velocity. Until new suppliers come in to increase supply (move the supply curve, instead of just increasing the quantity supplied), this is what happens. First year microeconomics.

Well, raising prices when "everybody" is expecting prices to rise works just great.

* First, the added profit!

* Second, it fuels inflation, and causes the guy in the White House -- a Democrat -- look bad.

* Better yet, with an election next week, jacking up your prices makes it more likely that the "Business Party" (they really give ya the business) will take over next year!

* Thus blocking all Democratic action, so they look even worse! And making the return of the Great Gawd Trump or a fellow traveler in 2025 inevitable!

It's "Business 201."

Companies can raise prices above and beyond the rate of inflation because America's consumers continue to purchase their products seemingly without any discretion. American consumers dutifully continue their transfer of wages and debt for goods and services despite being fleeced by the market. The pandemic has unleashed a demand that shall not be delayed. Companies reap the after tax profits with the same worthiness that Americans justify their immediate gratification.

Well, of course. Just another feature of the entitlement society. Corporations are entitled to price-gouging when they can get away with it, consumers are entitled to continue their wasteful spending habits. Because we are living the American Dream of endless acquisition.

We worship money. Countless Americans spend a great deal of time listening to news about, and playing, the stock market. (Well, at least it is a way to fight boredom. Maybe.)

And there is an added benefit for Republican CEO's. Inflation during a time of Democratic political control will help put the Party of Big Money back in power.

That's because price markups (for the sake of profit, beyond just what the cost increases were) are largely responsible for the inflation we're seeing to begin with.

Why is this surprising?

I am continually astonished that economists never seem to mark their beliefs to really The FED insists on fighting a surplus of demand inflation when it is perfectly clear that this bout of inflation is caused by lack of supply. How making capital more expensive is supposed to hasten increased supply is not at all clear to me.

An example of lack of supply is milk. When COVID hit, demand for milk went way down. Creameries cut their purchases from dairy farmers, who in turn had to cull their herds. When Trump decided COVID was over, demand for milk returned, but it takes years to build herds back up. So the price of milk went way up. Economists don't understand this because they only understand

spherical cows

No one has the guts to do anything about it, or rather not enough someones.

Pingback: Wages versus Product Markup - Angry Bear

Pingback: Wages versus Product Markup - POSTOLINK