Back when I was a tiny tot—let's say around 1990 or so—I learned that the Federal Reserve controlled monetary policy via open market operations that influenced short-term interest rates (the "fed funds rate"). High rates slowed the economy and low rates gave the economy a boost. The Fed pushed the fed funds rate up and down by buying and selling Treasury bonds on the open market.

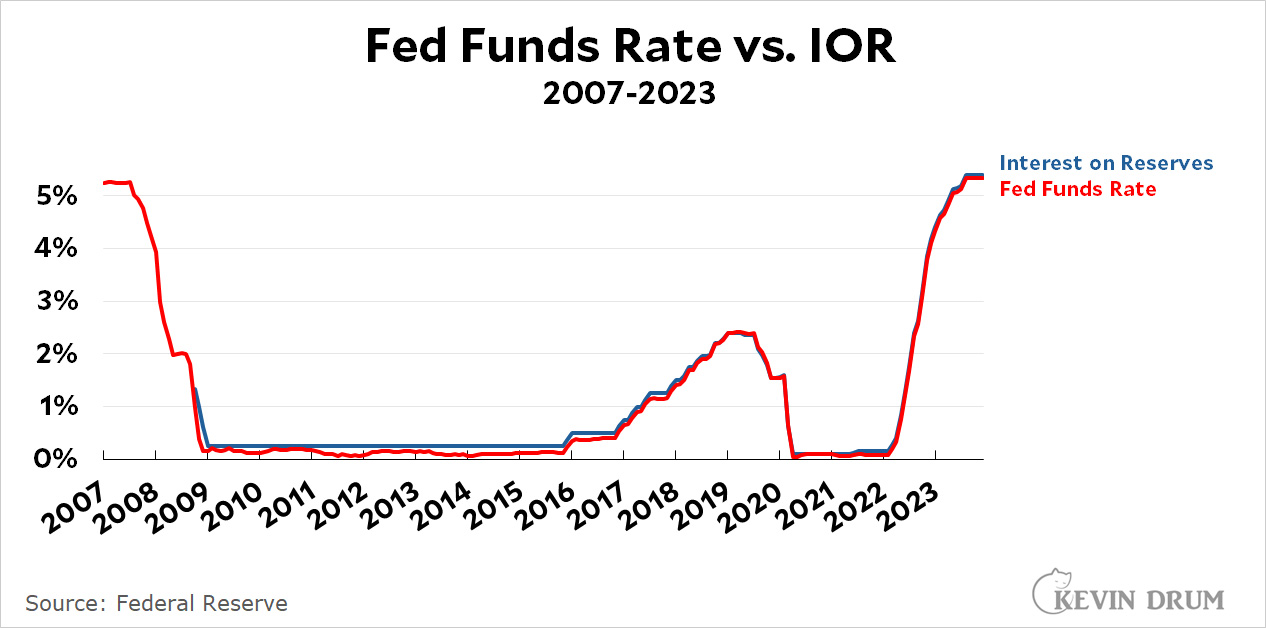

Today, Peter Coy comes along to tell me I'm way out of date. The Fed no longer relies on open market operations to influence interest rates. Instead, it just changes the rate it pays banks on their reserves. If, say, the Fed is paying 5.25%, then short-term bank rates will automatically increase to 5.25%. After all, if a bank can get that much just by letting its money sit safely at the Fed, why would it ever loan out money for less? Here's a chart that shows how both rates change in tandem:

In March 2022, the Fed started to raise the interest rate on reserves and the fed funds rate followed right along.

In March 2022, the Fed started to raise the interest rate on reserves and the fed funds rate followed right along.

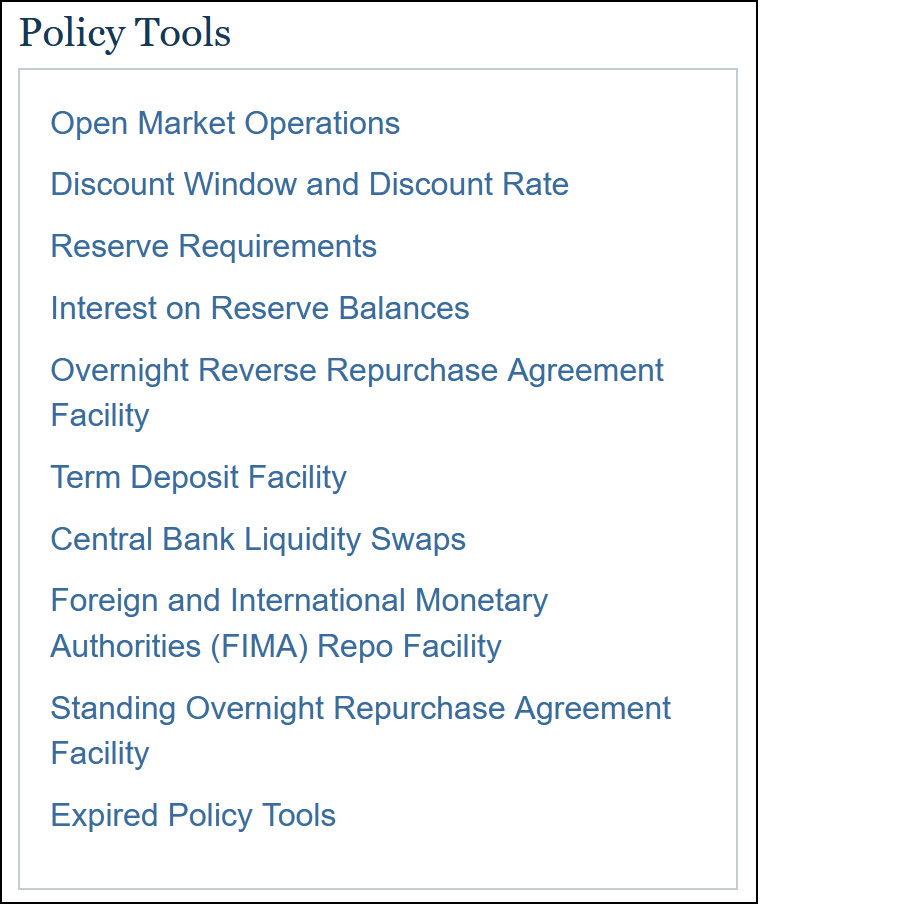

Coy wants to know why it's taken so long for textbooks—and all the rest of us—to get the message that things have changed. I may have the answer. For starters, here's what you see on the Fed's Monetary Policy home page:

You'll notice that "Open Market Operations" is still at the top and "Interest on Reserve Balances" is #4. If you click on these, open market operations are described as a "key tool" while interest on reserves is described as an "important tool." This doesn't exactly drive home the point that open market operations are dead.

You'll notice that "Open Market Operations" is still at the top and "Interest on Reserve Balances" is #4. If you click on these, open market operations are described as a "key tool" while interest on reserves is described as an "important tool." This doesn't exactly drive home the point that open market operations are dead.

There's also the Fed's Open Market Report, which says things like this:

The Federal Reserve implements monetary policy in a framework that includes a target range for the federal funds rate to communicate the FOMC’s policy stance, a set of administered rates set by the Federal Reserve, and market operations directed by the FOMC.

It's true that "administered rates" comes before "market operations" in this paragraph, but again, it's hardly a clarion call about open market operations being dead. There's also this:

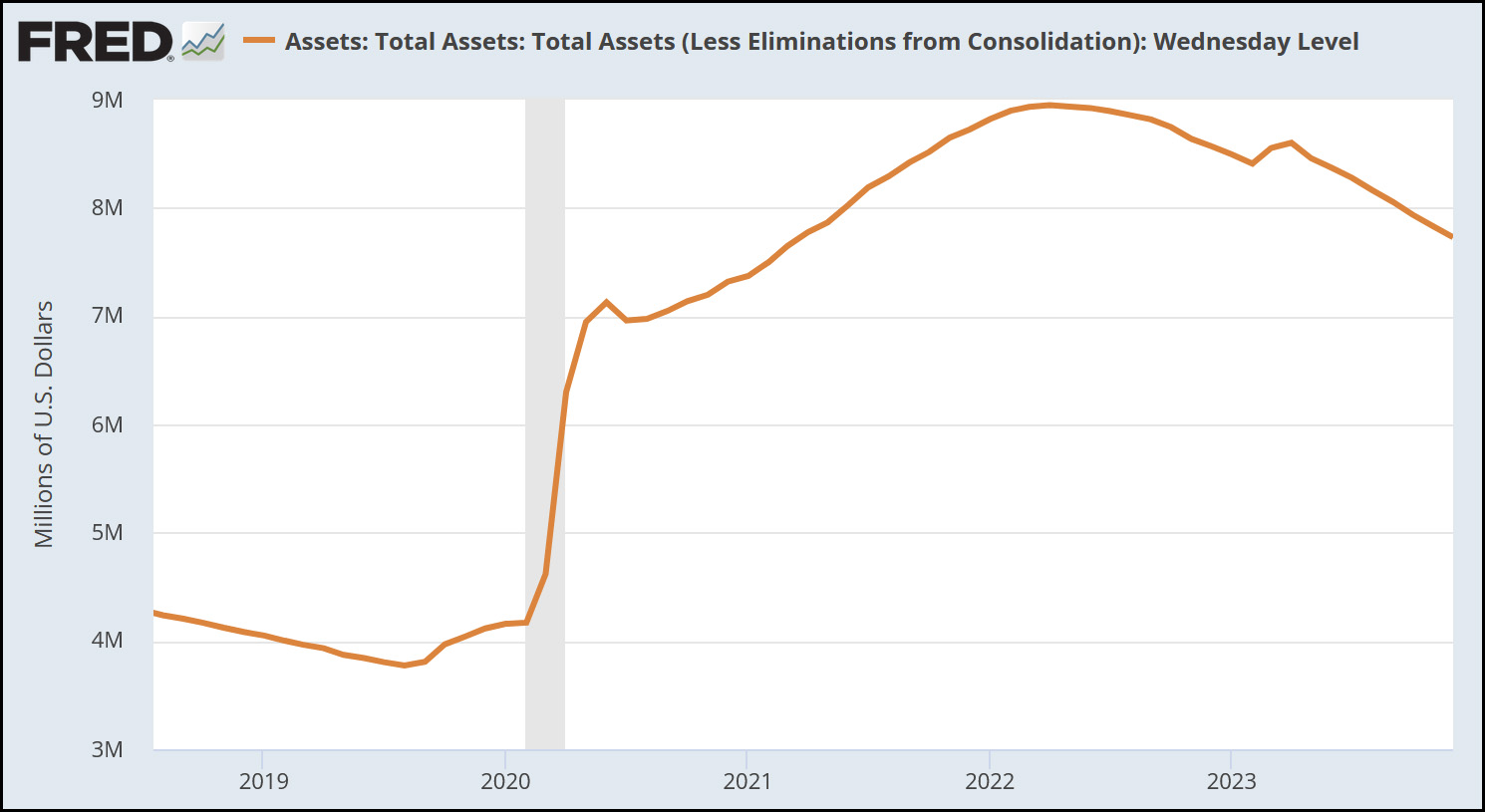

This is the Fed's balance sheet. As you can see, it went up considerably at the start of the pandemic in order to keep monetary policy loose, and then started to decline precisely in March 2022, when the Fed wanted higher interest rates. That's "quantitative tightening," which is a form of open market operation targeted at longer-term interest rates. So open market operations have changed, but aren't really dead.

This is the Fed's balance sheet. As you can see, it went up considerably at the start of the pandemic in order to keep monetary policy loose, and then started to decline precisely in March 2022, when the Fed wanted higher interest rates. That's "quantitative tightening," which is a form of open market operation targeted at longer-term interest rates. So open market operations have changed, but aren't really dead.

Finally, there's the question of what the Fed would do if the economy went sour. No bank will loan money for less than the interest rate on reserves, so the Fed can always force interest rates up. But what if they want to force interest rates down? Even if they reduce the reserve rate to zero, there's no way they can guarantee that banks will follow suit. It still might make sense for them to keep their rates higher than the Fed wants. If that happens, then hello open market operations! They'll be back.

Now, it's true that in 2019 the Fed said this:

The Committee intends to continue to implement monetary policy in a regime in which an ample supply of reserves ensures that control over the level of the federal funds rate and other short-term interest rates is exercised primarily through the setting of the Federal Reserve's administered rates, and in which active management of the supply of reserves is not required.

That's clear enough, and Coy is right that this is the company line for now. All I'm saying is that the Fed hasn't exactly shouted this from the rooftops. It's hardly any wonder that so many of us—even textbook writers!—have been a little slow to update our brains.

POSTSCRIPT: I feel like I have to add something here. If controlling the fed funds rate is as easy as changing the interest rate on reserves and then pressing Enter, why did the Fed ever do it differently? Open market operations are a helluva lot more complicated and labor intensive.

Isn't it a new thing for the Fed to pay interest on reserve deposits? An emergency measure of some kind? Or am I remembering this wrong?

The Fed was authorized to pay interest on reserves in 2011, I think. There wasn't much publicity about the change at the time, or about the Fed's elimination of reserve requirements.

Wasn’t the balance sheet basically zero before 2008?

Per official and other sources unearthed by Dr Google, paying interest on reserve deposits was in part a response to the near-collapse of the banking system in 2008. New authority to start paying this interest in 2011 was given by a legal change in 2006 but implementation was moved up to immediate in 2008. At that time it was a way to get money into banks' hands when they really weren't doing/couldn't do any lending, and banks put huge amounts of money into excess reserves far beyond what they needed to maintain, in order to bring in the interest income.

A San Francisco Fed paper from 10 years ago points mainly to the interplay between interest on reserves and the fed funds rate for overnight interbank lending, which had been one of the Fed's traditional tools. At that point the relationship looked reciprocal, but it seems like they were still figuring out how it was working in practice. https://www.frbsf.org/education/publications/doctor-econ/2013/march/federal-reserve-interest-balances-reserves/

So offhand it looks like they've been learning over an extended period how banks and the economy react to various moves they make with their different facilities. And as circumstances change, so could the ways banks react. If I had a taste for bad puns I'd say it's a fluid situation ('cause so many fluids are liquid).

I believe it was just a few years ago where we were facing the (Z)ero (L)ower (B)ound. It appears you don't recall, or you did not pay attention, to what was proposed the Fed do in this case.

Don't forget about the "negative" interest rates.

This.

What do you think QE was/is?

The Fed IN THE OPEN MARKET bought long term assets to bring down long term interest rates.

Why does the market know with 95+% certainty how the Fed will change rates at its meeting? Because the Fed signaled the answer in THE OPEN MARKET.

They meet once every 7 weeks. How do they work with interest rates the other 34 business days? By the work they do IN THE OPEN MARKET.

Can the Fed force interest rates down?

There's two kinds of interest rates; one being the rate that a government like the US pays on risk free liabilities like Treasury securities and Fed reserves, and the other being a rate charged to borrowers based on risk of default.

The rate on risk free Government liabilities has always been exactly what the Government wants it to be, and US Government liabilities have been risk free ever since gold convertibility was abandoned. The risk free interest rate is a floor, since no bank will put money at risk unless they can do better than the rate they get just from parking money at the Fed.

The risk based rate is just that, set by commercial banks on a competitive basis.

If you studied MMT you'd know all this.

So me rates are set by the "market", others relative to discount rate, and others are what you'll pay now for the nominal amount later.

https://www.treasurydirect.gov/marketable-securities/

One other point, since the textbook-lag complaint is what started this all. Texts get revised on a cycle. I don't know how long that cycle is but have to think it depends in part on how widely used any particular text is, how committed authors and publishers are to keeping it current, the state of authors' health, things like that. Within that, authors and editors have to set priorities for what needs revising, which will depend largely on the state of the literature, ie what economists are paying attention to.

Between 2008 and 2022 it seems to me there was a lot going on in the field, some of it pretty consequential rethinking, that revisions simply had to deal with. This particular point, in that context, is really kind of small potatoes, and I'd bet there hasn't been much in the literature on it. Meantime the Fed's websites on the topic-- probably not a high priority there either, tbh-- have been making some changes to sort of keep up. More comprehensive filtering down to the textbook world probably awaits some settling down of bigger issues.

Honestly, I think this hook is more an opportunistic gotcha on Coy's part than anything else.

Pingback: Stevenson’s army, January 18 - peacefare.net

There is some truth in what Coy says, in that other things have at least partly taken the place of traditional short-term open-market operations. But these things include open-market operations on long-term bonds (QE) and short-term reverse repo operations, both of which have amounted to trillions in the last few years. If the rate on reserves really set a floor on federal funds rate, the reverse repos would not be needed. And clearly the massive QE operations were intended not just to provide bank reserves, but to reduce long-term rates, that is presumably to set a ceiling on them.

Coy appears not to understand everything the Fed has been doing, and frankly I don't either - it's too complicated. But the disturbing thing is that the Fed has never really understood what it is doing either. Its own literature is contradictory. It keeps changing its objectives and methods when the current methods don't work.

Pingback: 10 Friday AM Reads – Wise-Compare

Pingback: 10 Friday AM Reads - The Big Picture

Pingback: 10 Friday AM Reads - The Large Image - KYFOL

Pingback: Links 1/24/24 | Mike the Mad Biologist