The Guardian has a dramatic headline today:

A groundbreaking study shows kids learn better on paper, not screens.

I apologize in advance for going down a very long and very complicated rabbit hole on this, but you can always scroll past it if you get bored. Needless to say, I got curious and decided to read the paper it was based on. My brain nearly exploded.

In a nutshell, a team of researchers hooked up a bunch of kids to EEG helmets and measured their responses to reading cues. Some kids were tested after reading narrative passages on a screen while others were tested after reading the passages in print. So far, so good.

But here's where it starts to get complicated. The kids read the passages and were then presented with "probe words." The words were either related to the passage, unrelated, or sort of related.

The theory here is that you have a stronger EEG response to new things. Thus, if you had good comprehension of the passage, you should have a weak response to related words since you've already seen them and a strong response to unrelated words because they're new to you.

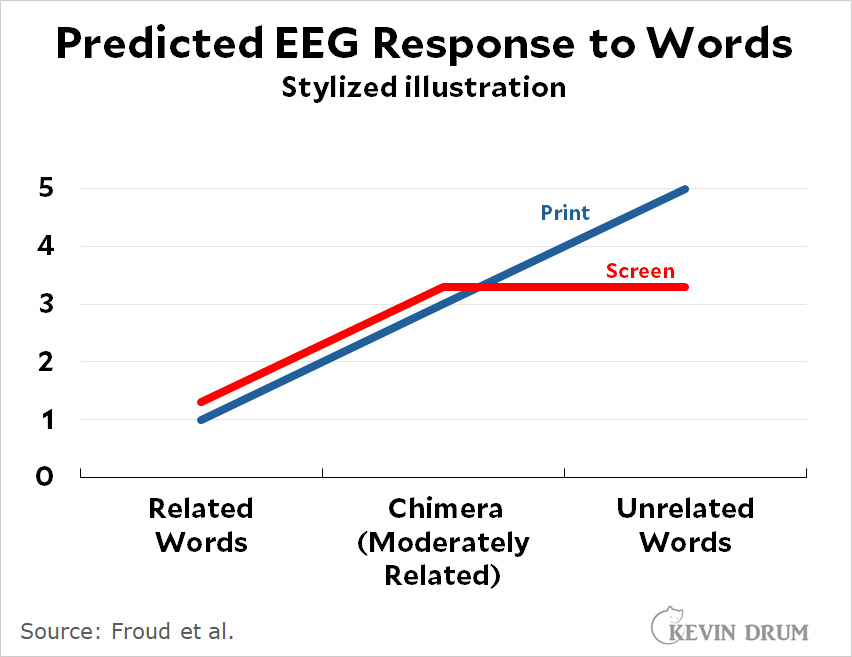

So the authors made a prediction for reading in print vs. reading on a screen. Here's the prediction:

In the print scenario, response would get steadily stronger as words became less related to ones the kids had seen before. But in the screen scenario, there would be no difference between moderately related and unrelated words.

In the print scenario, response would get steadily stronger as words became less related to ones the kids had seen before. But in the screen scenario, there would be no difference between moderately related and unrelated words.

Why? I have no idea. There's a bit of handwaving late in the paper, but I can't say that I found it very convincing. Note that "chimera words" are those that are moderately related to the text:

Whether chimeras are perceived as related or unrelated to the text may depend on the strength of the encoded memory traces established during text discourse processing. Therefore, perception of chimera words as unrelated words would be consistent with shallow discourse processing as hypothesized in digital text reading, whereas chimera words perceived as related would be consistent with deeper discourse processing as observed in print reading.

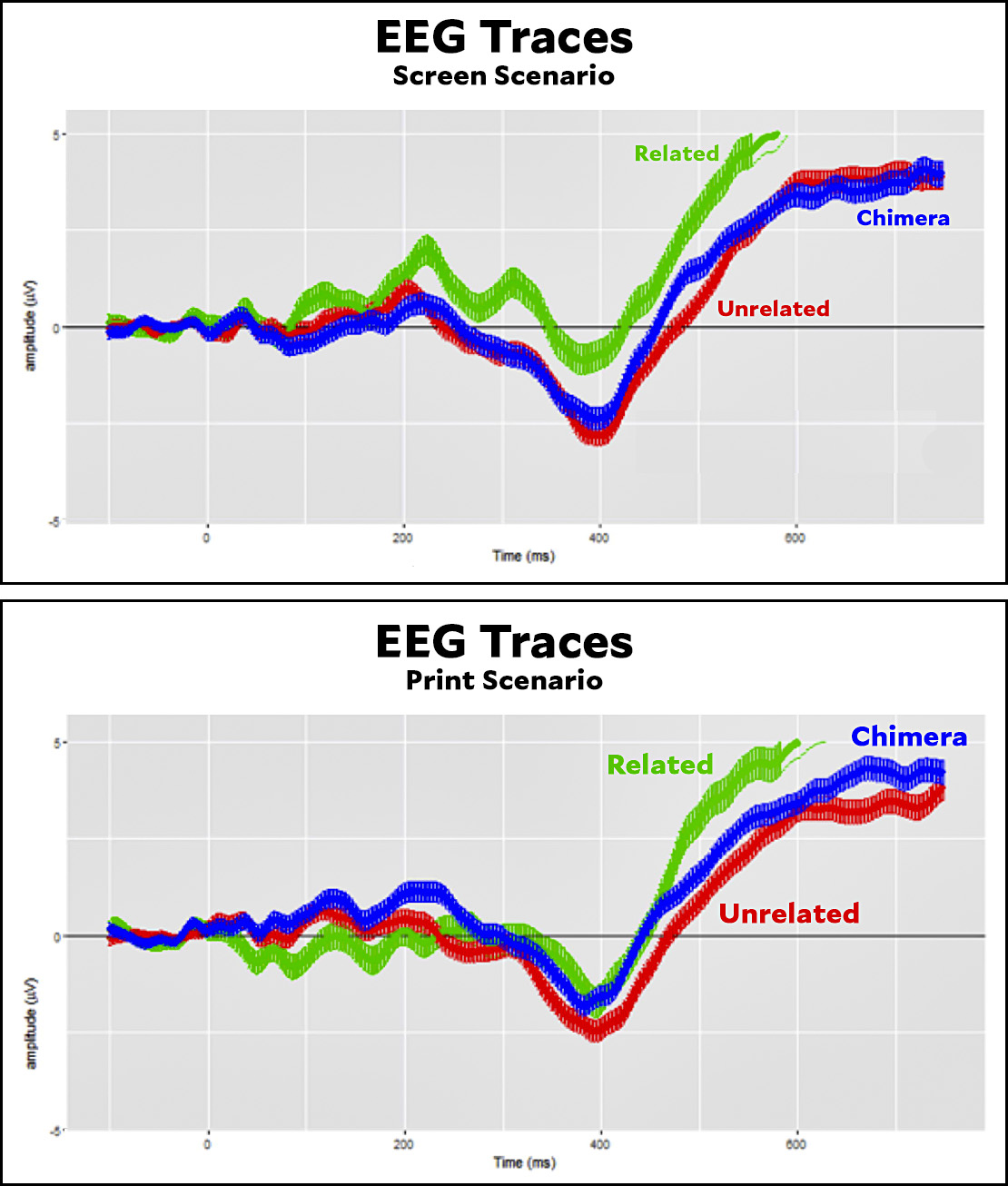

Hmmm. Anyway, here are the results:

These look pretty similar! But it's true that in the screen scenario the chimera words and the unrelated words are nearly identical at the critical 400 μsec mark. In the print scenario, there's a small difference.

These look pretty similar! But it's true that in the screen scenario the chimera words and the unrelated words are nearly identical at the critical 400 μsec mark. In the print scenario, there's a small difference.

On the other hand, in the print scenario there's no difference between chimera and related words. This doesn't confirm their prediction.

And related words have a noticeably weaker response in the screen scenario. Unless I missed it, the authors don't discuss this.

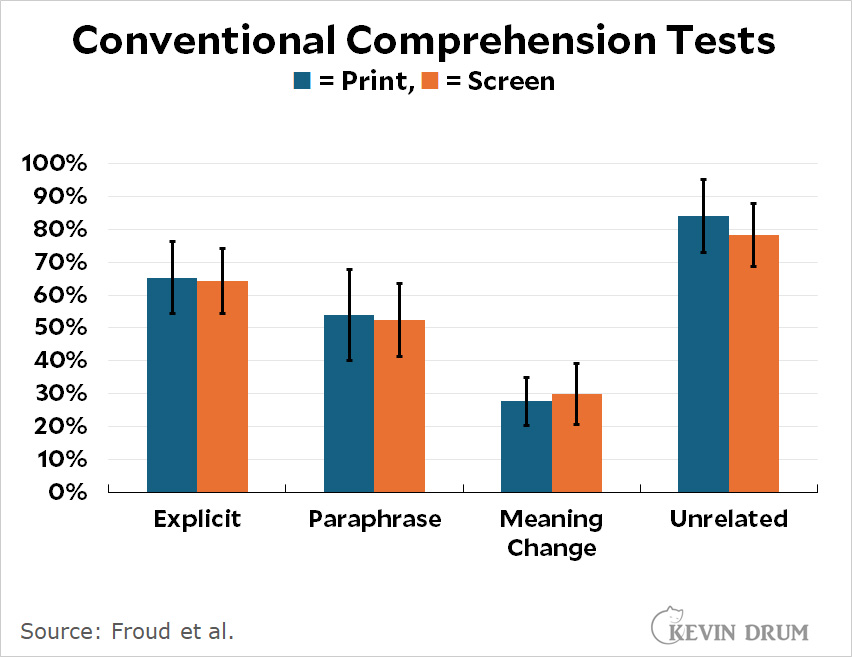

But there's more! The researchers also performed some ordinary comprehension tests. Check it out:

There is virtually no difference between print and screen, and what difference there is is dwarfed by the error bars.

There is virtually no difference between print and screen, and what difference there is is dwarfed by the error bars.

NUTSHELL SUMMARY: A ton of work went into this. However:

- The sample size is small (59 children).

- How do we know if a word is "moderately" related to a text passage? The authors picked words using software and then had a hundred random adults rate them. There's a good chance the results are all but meaningless.

- The authors' prediction is extraordinarily indirect. How sure are we that the difference between high and low comprehension will show up specifically in the response difference between moderately related words and unrelated words?

- In any case, the prediction was only barely borne out.

- And in the print scenario the response is virtually the same between all words. This definitely does not support the hypothesis.

- And the absolute response to related words is weakest in the screen scenario, which means the kids were very familiar with them. This is fairly direct evidence of greater comprehension in the screen scenario.

- Finally, in an ordinary test of comprehension, there's no difference at all between screen and print. This was true at the time of the test and on a test administered a day later.

Color me unconvinced. Maybe I'm missing something, but the prediction is so roundabout and the results are so minuscule that I have a hard time believing there's anything here.

POSTSCRIPT: Ah. At the bottom of the Guardian writeup we're told that the author "participated in the fundraising" for the study. That certainly explains the enthusiasm of the headline.

Can we move on to cat blogging?

There have been numerous other studies -- not using this EEG data, afaik, and not all with kids -- that show fairly significant advantages of print over screen when it comes to retaining or digesting information. And in my own teaching, I can say I get (or at least I *feel* I get) more productive discussions and insight from the group when they've read something on physical paper, especially if they're able to take notes, write down questions, etc. Yes, you can markup a pdf on your laptop or whatever, but it's kind of a PITA as opposed to just scribbling with a pencil in the margins.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/time-travelling-apollo/202203/why-we-remember-more-when-we-read-paper#:~:text=The%20vast%20majority%20of%20studies,do%20from%20an%20electronic%20device.

Yes, I often see studies on the benefits of print over screen for comprehension. Also on the benefit of taking notes by hand vs typing them.

Totally anecdotally, I'm seeing less recall from ebook users. My book club is full of ebook users and a couple of text readers, and every meeting the text readers mention things that happened in the book that the ebook people don't remember at all. It may be an issue of what ebook listeners do - they often speed up the book and do other things at the same time - but they clearly can't resist the temptation to do things that limit comprehension.

The long-haired girl near the center of your image has three arms.

Good catch. Looking closely at the picture I would guess it’s AI generated. Note the disembodied arm at the third desk to the left of the “girl” you noted. Also the monster unhelmeted heads floating by the windows.

The picture caption says it's 'AI-assisted'. You must be reading on a screen.

: )

Oh, sure, but think how much faster you'd have spotted it, had it been printed on paper.

/s

This is an enormously funny image. On the right hand side, there is a keyboard, but no screen. The right hand of the person appears to have "too many" fingers (I think it's 7). To the left of the extra arm girl, are two students typing with no screens. To the left of them and slightly behind, is a screen that may be floating. Above that is a headless (looking) person. There are screens not facing pupils. Between the windows, the person is so small maybe they appear to be a doll because they don't have a torso/bottom half. The person in the lower right appears to not be reading anything, but hooked up (control subject)?

This is like a "how many things are wrong with this image?" puzzle.

Thanks for pointing out the extra arm girl and giving me motivation to look harder!

This is your AI on drugs.

There are way more oddities than just that. A disembodied leg, a mutated double hand, kids staring at the backsides of monitors, an adult female sitting down as a student...

When I was working, I needed to print out documents that required a critical or technical review or potential modifications, while I could manage to review/modify more casual types of written communication on screen. When drafting something critical or technical, I learned to write it on screen but needed to print it out for review.

Of course I have a rather ancient brain and didn't grow up with screens as part of my life, but for the 19 inch B&W tube with rabbit ears, that had a whopping 7 stations available.

I was an investigator on a contract-research study comparing paper documents to a second screen, used as reference when preparing reports. Screens were fine, and eliminated substantial delays in retrieving and switching between reference documents. The whole process involved a central facility and local offices, so retrieval of physical documents was nontrivial.

Yet another exhibit in my gripe bag of "most social 'science' studies are crap" cases.

In a tangentially-related item, I heard on last night's news that the local school system was planning to address its continuing reading problems by switching to an entirely new system of teaching how to read, which had been found to yield results (and I quote) "a full one percent better" than the system they're using now.

As Charles Pierce might have said, "Jesus wept."

Half-a-percent, half-a-percent, half-a-percent onward ...

The authors aren't the sharpest knives in the drawer, but the study usefully demonstrates that, for the measure that actually counts, namely comprehension, there is not a significant difference between screens and paper*. The EEG differences, even if real, don't seem to matter for what we actually care about.

But as always in human studies, more research could be done. What's the comparative time course for fatigue when reading on a screen, vs. paper?

*This is a single study and replication is essential in human-performance research.

There's probably not that much schools can do to increase reading levels beyond what they are now, so districts latch onto any gain they can, however small.

Schools can add phonics instruction pretty easily, and there is only so much phonics instruction that the average parent is capable of. Explicit phonics instruction is helpful for many kids, but phonics at school can only get you so far with reading.

The rest of getting every chold to learn to read is much more complicated. Identifying learning disabilities isn't always easy, especially when kids miss a lot of school or switch schools frequently. Vocabulary and content knowledge development are still extremely influenced by home life.

If a kid has a limited vocabulary and little knowledge, phonics may help them sound it out, but is not sufficient for comprehension.

I suppose it might have been microseconds, but the x-axes of the charts are labeled as milliseconds.

400 microseconds is a really short time..... Neuron signals are not radio waves.

If really significant differences had been found in conventional comprehension tests it might make sense to do the EEG tests to find out what is going on. However that may be the authors destroy their own case with Kevin's last graph. Who cares what the brain waves are doing if there is no significant different in actual comprehension?

There is certainly no evidence from the study that everything has to be done on paper.

Agree.

I think this is another case of media mangling and overplaying scientific studies. These types of granular experiments can be useful for figuring out some of the mechanics of a process, but it's not a great way to measure the whole process. EEG detected brain stimulation is a proxy for comprehension, but it doesn't seem like a great one (especially based on that last graph.) If you want to measure learning, sometimes you have to measure learning. Proxies only tell you so much.

I think there are several unnoted potential complications to properly drawing conclusions. An imbalance of neurodivergent kids might complicate the outcomes, particularly because EEGs are being used. Fonts present differently in print vs screen. Some fonts slow down reading comprehension, as well. On paper the text is likely 9 or 10 pts, but is it the same on the screen, or is it actually 8 or 8.5?

Agreed. This is a really loose study. How well lit were the paper items? Was there any background noise or other distractions? What kind of screens? Between the worst screens and the best screens there is a huge difference in readability.

When you next turn to AI for help with an illustration, try asking for less dystopian.