Back in the day, we all worked for the same company our whole lives. Today, though, we job hop like frenzied rabbits. Right?

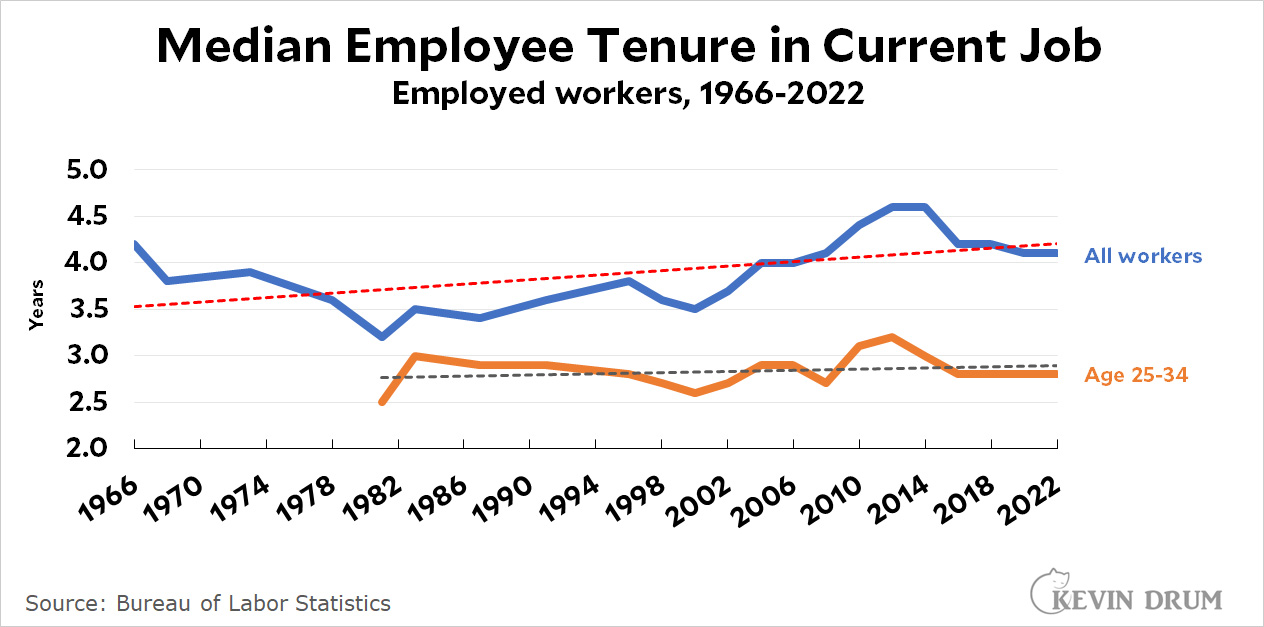

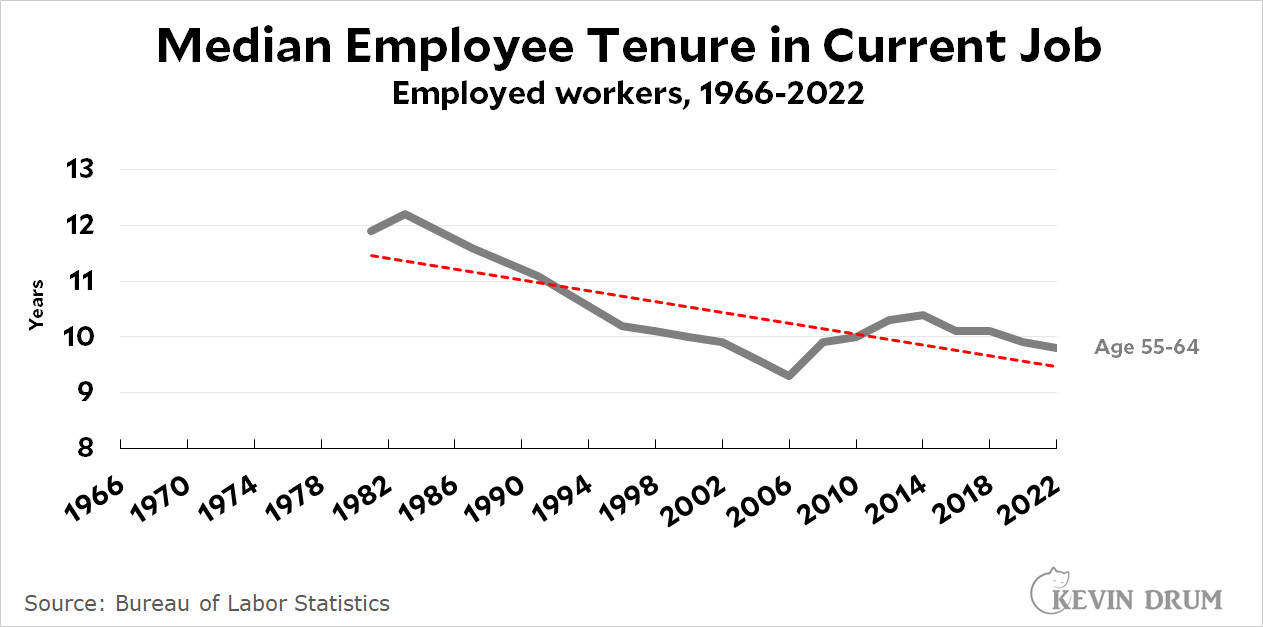

Apparently not. Median job tenure has increased considerably over the past 50 years, though some of that is due to the aging of society (older people have longer job tenures than younger workers). But even if you restrict yourself to a single youngish age group, job tenure has still increased. However, there's an exception: among workers at the end of their career, there was a significant drop through the mid-90s:

Apparently not. Median job tenure has increased considerably over the past 50 years, though some of that is due to the aging of society (older people have longer job tenures than younger workers). But even if you restrict yourself to a single youngish age group, job tenure has still increased. However, there's an exception: among workers at the end of their career, there was a significant drop through the mid-90s:

Generally speaking, job tenure has been steady or up over the past half century. We don't job hop any more than we used to. However, the share of older workers with very long job tenures (ten years or more) has dropped from 59% to 50%.

Generally speaking, job tenure has been steady or up over the past half century. We don't job hop any more than we used to. However, the share of older workers with very long job tenures (ten years or more) has dropped from 59% to 50%.

Speaking as one, older workers with longer job tenures were got rid of, either just before we turned 55 or afterward through dodges like "job reclassification" (or elimination or relocation), because we were seen as expensive, both in terms of salary (having accumulated raises steadily for years) and in (perceived) health insurance costs. I wouldn't even call it an open secret, because it wasn't really secret.

Whether it has turned out to have been good for companies in the long run isn't clear to me. Older workers with long tenure are where a company's institutional memory resides, and they tend to be loyal (why switch now, they ask) and to have been through ups and downs, so they tend to put up with a lot without (much) complaining. Younger workers are definitely cheaper and often (although not always) more energetic, but they don't know stuff, they make more mistakes, and they'll pick up and leave for little or no reason, and all that's even more likely to happen when their managers have little or no more experience than they do.

Speaking strictly personally, I was lucky (or I had prepared well), so it didn't hurt much. But I can say without reservation (and said to them at the time): getting rid of me was a mistake on their part, and subsequent events have shown that clearly.

Similar experience — laid off (from my second employer after graduate school) at 53. Previous round of layoffs had included so many senior staff that the company was sued for age discrimination. So my cohort was sprinkled with junior people until the lawyers thought it would pass.

My last dozen working years were spent as a contract employee in a government research center; same role, three different employers, due to a contract re-compete and an acquisition. So, lifetime, one 17-year tenure, four of seven years or fewer.

How much job hopping has Mr. Ohtani done so far?

Just to pick a nit...

There is a difference between at current job and working for same employer for wages or salary. Promotions and transfers mean you're not at the same job but could still be working with the same employer.

Data doesn't go as far back you what you have:

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/tenure.t01.htm

You certainly are more adept at finding data on government sites than I. The longer term trends are definitely useful.

It would be interesting to see this separated by gender. Those 1966 workers were mostly men, and those 2024 workers are almost equally split, which might make a difference.

golack makes a good point too.

Pretty sure the "less job hopping" phenomenon is related to de-industrialization and the rise of the service sector (and, relatedly, the increase in education attainment). Although you might not know it listening to popular takes, the economy of, say, the 1950s, was likely characterized by less job stability than our current era, because of compositional effects. Sure, Ward Cleaver seemed to enjoy a job for life. But in those days there were much larger numbers of casual workers involved in things like forestry, mineral extraction, construction, agriculture and yes, manufacturing (Some factory workers enjoyed long tenures, of course. But not every worker in manufacturing spent 35 years at a GM plant. Many worked for small firms where there was plenty of churn, layoffs etc). And today, of course, a lot of the service workers are employed in sectors like healthcare, finance and education, where employment tends to be pretty stable.

This strikes me as a very simplistic analysis. A lot more context is needed before you can make a meaningful conclusion.

For example, there's no information about *why* people are changing jobs. How much of this is voluntary?

The overall numbers are about right for my own career, and for most of my friends and coworkers, but many of those job changes were due to layoffs. I hate the entire job search and interview process and more than once have been laid off from jobs where I would have been happy to stay there until I retire. I suspect that's true for many people, and probably was true for the entire 50-60 years of this data set.

I'm in the > 65 group and I choose to stay employed. I'd bore my wife to death if I stayed home.

Tenure in current job is 18 months. Previous job was ~2.5 years. The one before that ~1.5 years.

There is a lot of truth to the idea that changing jobs every 2-3 years is the only way to build up your salary. Getting hired at X and then getting a 1-3% COL salary increase every year wont keep you ahead of inflation. There are a lot of people who have been in a company for 5-10 years and the new people are being hired on at a much higher salary than the tenured employees.

I've done both, I worked at one place for 13 years and then have spent the last few years spending 1-3 years at a few companies. The downside to having a good salary over 100K is that it makes you an easy target during layoffs. So pick your poison I guess. I would rather make more and save more than try to get by on COL increases.

I suspect that the narrative of more job-hopping nowadays is specific to the educated, professional class. Lower-income workers have always been more precarious, but they don't write much, so their experiences don't form the narrative; the white-collar set tells the story, so their experience is the story we hear.

I realized this a while ago after looking at a chart of the numbers of dual-income and male-only-income couples over time. In the 1950s there were a LOT more dual-income couples than the narrative would have you believe, and that's because it was a class thing: wives didn't work if their husband made enough to support the family on one income, but did work if he didn't make enough on his own. The narrative of stay-at-home moms in the 50s giving way to working women in the 70s and 80s was a real phenomenon, but it was specific to the higher income brackets.

So I think it really is true that for-profit companies are less likely to give lifetime employment to white-collar workers nowadays than they used to be, but that is canceled out in your chart by reduced precarity in worker categories who don't write much.

The shorter tenure for retired people could be driven by more retired people working for McDonalds and walmart since they can't find kids for those jobs.