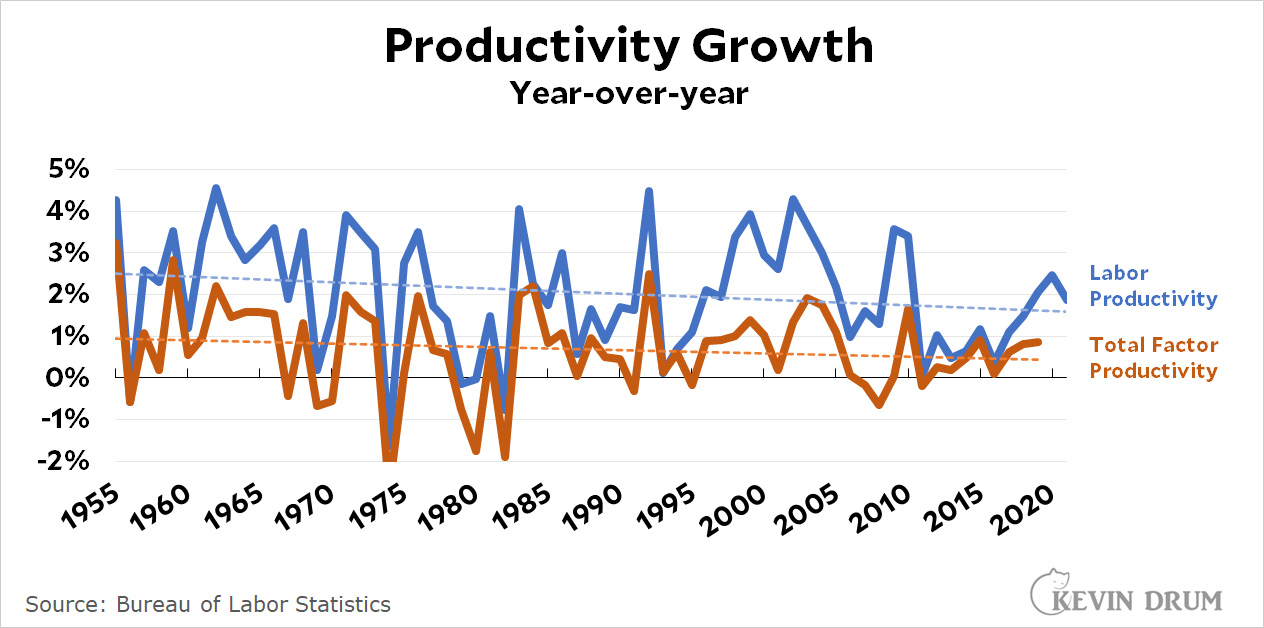

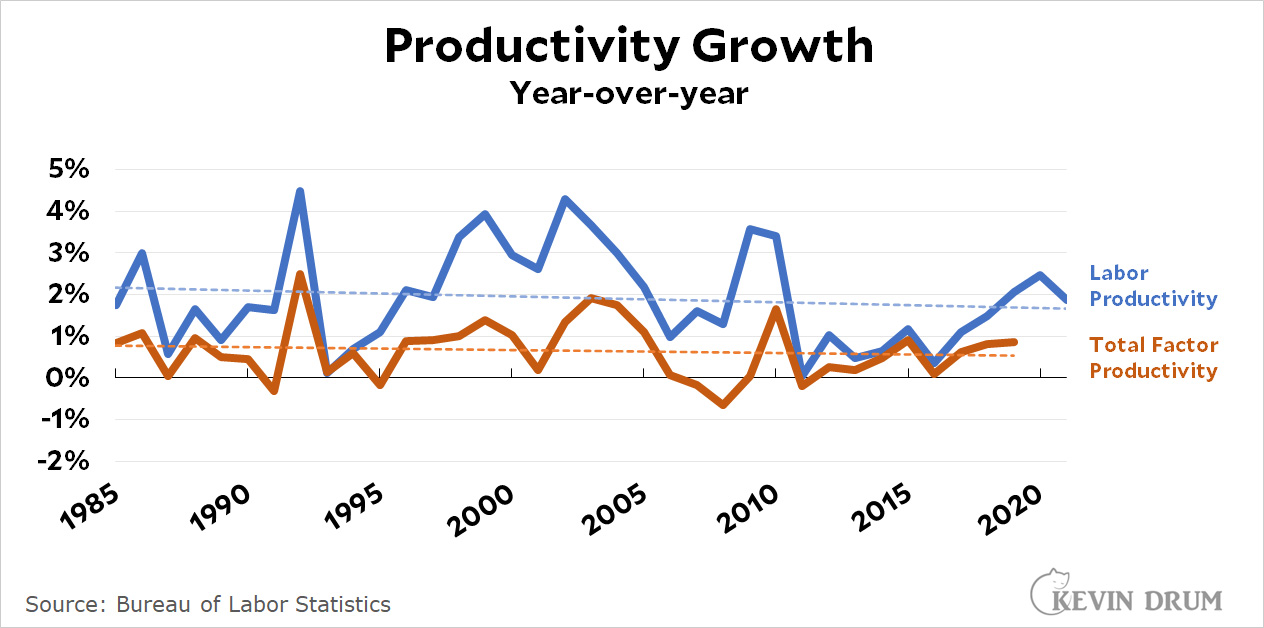

I have no special reason for posting this. It's just to remind everyone that, in the end, productivity growth is the single most important metric of economic prosperity and ours has been slowly declining in both the medium and long term. We should ask our presidential candidates what, if anything, they plan to do about this.

POSTSCRIPT: Here's something I've never understood about productivity growth: why is it so volatile? It's always struck me as something that ought to be fairly steady, especially if you remove recession years. But it's not. Why does it swing up and down so frenetically from year to year and even quarter to quarter?

Does anyone know what the productivity picture generally looks like for other rich countries? Is their rate of productivity growth likewise declining over the long term? I don't see any of them racing ahead of the US in terms of per capita output so I suspect it's a generalized trend related to things that aren't particular to the US. But I could be wrong.

O/T: anyone see the Fetterman-Oz debate? Some are saying Oz had a good night because Fetterman's medical condition was on display. Some say Fetterman had a good night because of Oz's abortion gaffe. Which is it?

Both?

The problem is that our politics is at such a state of trench warfare, it doesn't really matter. I and most everyone here see Fetterman's "gaff" as immaterial (he can function as Senator just fine, thank you, despite his stroke-induced speech issue) while Oz's revealed just what a lapdog for the Christian Right he will be. Whereas staunch GOP voters - even ones who lean toward women's right to choose - will latch onto Fetterman's difficulties in a debate forum as an excuse to vote for TV-cure conman, because, well, he's generally on our side.

Then we should be talking about how to make this not the case, because "you have to grow, forever, without limit, and if not you're fucked" is not desirable or sustainable. The massive productivity gains of the past two centuries are a massive historical outlier and it should not be assumed they'll be an endless new normal. Absent constant, unending revolutions on the level of "the steam engine" and "the personal computer" we have to assume that eventually year-over-year productivity gains will return to their historical norm of one or two percent a year, and be planning on building an equitable economy around THAT.

Do you see any reason to believe that "constant, unending revolutions" will NOT be the norm for the foreseeable future?

The claim that constant, unending revolutions will be the norm is so extraordinary that I feel like the burden of proof is on that side of the equation rather than the other side.

Depending on exactly how you define the terms "constant", "unending" and "revolutions", we've been seeing constant, unending revolutions for between two and five centuries, and the pace of technological change has been accelerating that whole time. It would take something extraordinary to reverse that trend.

Did you misread the chart? Total factor productivity has been increasing at 1% or lower per year since 1955, on average.

Productivity increases don't necessarily result in increased production. They can result in lower prices, or increased leisure. In fact we've enjoyed a combination of all three since the industrial revolution.

With so much volatility, how meaningful are those trend lines? Eyeballing it, I don't see much evidence that productivity is steadily decreasing. 2010-2015 seems like a weak patch, but it also seems like the whole trend is based on that.

Productivity growth is the most important thing to those who benefit from it, but over the last 50 years people with median and lower income have not been getting their share. The growth of inequality has cancelled out productivity growth for them. Kevin thinks he is progressive but he often ignores this.

A bigger pie means more for everybody, on average. Distribution of that pie is a matter that needs to be addressed, but it's a different issue that growing the pie.

I'm not sure you can split the two issues. The mantra of the right is that inequality is not an accident, it's part of what drives growth. And on the left there's the belief that general well being - the common weal - is more important than growth uber alles. Like a lot of problems - think of the simple case of heavy traffic at an intersection. To maximize throughput you let one line keep going until there's no one left and repeat with the next line. of course If the traffic's heavy you may be unlucky and be the in last line of traffic to move and miss your appointment or be late for work. Conversely only letting one car through before switching lines creates a lot of wasted startup time. Balancing the two variables - throughput and equitable access is not a simple thing. We baby boomers grew up in an unusual period of several decades of great growth that was mostly shared by all . Then as the American post war boom slowed the evil geniuses on the right got to work and made sure they kept getting theirs ... and more. In any case, there's a larger context, the one libertarians and conservatives usually forget and that is that if all you do is maximize throughput at the expense of equality you create an unstable society that needs to be kept in line by force.

It's only in the US that the idea that "inequality is not an accident, it's part of what drives growth" is carried to the extreme of believing that no reduction in inequality is possible without killing growth. If you look at almost any other "first world" country, you can see that some inequality is accepted but that the extreme inequality seen in the US is generally not accepted.

A country can simultaneously maintain a strong social safety net and encourage economic growth. Many do.

Absent a stepwise change - ie some sort of breakthrough - I would expect productivity to asymptotically approach a limit.

There is no reason to believe that technological advancement will stop, or even slow down any time in the foreseeable future. There is a hypothetical limit to the productivity that is possible at a given technological level, but the technology advances so fast that we never approach that limit.

Here's something I've never understood about productivity growth: why is it so volatile?

Just a guess, but, over the short term, investment levels fluctuate quite a bit with the vicissitudes of the business cycle.

Not sure how this plays out in service industries, but for manufacturing, factories have some head space--so can ramp up production a little in good times, before adding more shifts and/or new lines, and fall back on production when things go south, before layoffs, etc. The former will give a spike in productivity, the latter a drop--but neither are sustainable in the long run.

Yes, basically the ratio is influenced by both leading and trailing indicators in both the enumerator and denominator. I would even argue that at any scale less than years it is effectively meaningless. It seems ridiculous that if workers are taking time to build a new assembly line that means they are not being productive. Our if they are increasing quality levels without the end sale price increasing productivity is at a stand still.

You should plot business cycles as well. The graph might make more sense if we know when, for example, mass layoffs occurred or sales suddenly slowed, or the reverse happened. I've been through enough layoffs to know that, for a short time, productivity zooms after a layoff as the remaining workforce struggles to do the same amount of work with fewer employees.

I would suggest that layoffs improve productivity mostly because it's generally the junior, which means less productive, workers that get laid off. Likewise, rapid expansion is going to cause average productivity to decline because the new hires will drag the average down until they become fully trained, experienced, highly productive workers.

I find massive fault with this logic. Indeed, it is the most junior employees who are usually the MOST productive. I've yet to work anywhere where the senior leadership was anywhere near as productive as the guys actually at the coal face doing work and making money. Hell, I've worked places where the janitors were probably the most productive people.

It's not the senior, or even junior, leadership I'm talking about. I'm comparing the guys who have been "at the coal face" or equivalent for years and have become very good at their jobs with the guys who have only recently arrived at the coal face and don't yet have the experience to keep up with the more senior workers.

Unrestrained, sustained productivity growth will become a real danger, as we become able to produce more stuff, fulfill more services with fewer people. What do the rest of us DO??

This is, after all, the United States of Calvinism, motto "If you don't work, you don't eat." How can we keep nearly all adults of working age "working"? What can they do, when the machines handle production (and note: even tractors now use GPS to run themselves, so bye-bye Farmer Jones). Only a limited number of humans will be needed to maintain and repair the machines, and Americans don't like the hard sciences ... or hard anything, it often seems.

Please do not suggest the "caring" services, keeping the elderly's diapers changed and spoon feeding them. Sure, more and more folks are needed for this work, but do we actually want a future of menial, degrading work? Which currently pays near nothing and depends upon the altruism of immigrants?

Farm towns have been depopulated already--that's why a lot of the people in the Midwest are upset--their kids go off to college and never come back. Stores in the "downtown" close because there's no one there--so quick runs to the "store" can take an hour or more. Older people yearn for the good old days, while trying to figure out how to cut costs (people) needed by buying new toys.

Fortunately, some Americans are able to look beyond the borders of the US to see the examples other countries are setting. Fundamentally, the US is going to have to accept that "If you don't work, you don't eat" is obsolete and a new paradigm is needed.

I wouldn't call it volatile. It doesn't usually change by a lot, but what changes there are are sort of random, not some regular gradual phenomena. So neither a 1% increase nor a 4% increase is all that remarkable, and one figure could follow the other at any time.

It's noisy and never changes. Meaningless data. How do you measure my productivity? You don't.

Here is the growth of a different measure of productivity, real GDP per capita

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=VhKK

This is more informative in some ways - don't we really want to know what the economy is potentially doing per person?

Going by production per hour worked, which is what Kevin shows, is useful for some purposes but it hides what happens in recessions, when both production and hours are reduced. Measurement of hours adds additional uncertainty, and hours worked tends to lag behind production, adding more variation.

Of course the distribution of the production is also important - most of the production for the last 50 years has been going to upper incomes.

Because people are people not robots. Sometimes you just don't have a great day.

Also burnout is becoming more widespread as employers demand more and more.

"Why does it swing up and down so frenetically from year to year and even quarter to quarter?"

Most likely due to measurement inconsistencies.

Why is it so volatile?

it isn't.

It is just very hard to measure and the tools for measuring it are not very accurate.

So we take a bunch of measurements with a significant margin of error and we end up with a volatile answer.

^This

As a concept, productivity is super important.

As a macro-statistic, labor productivity and total factor productivity trends are fairly useless.

But they are stats!

Here's a graph of real GDP divided by hours worked:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=VioK

It is pretty much a straight line with a kink after the 2008 recession at which point productivity growth slowed dramatically. It seems to have been rising again since 2018 or so. I have no idea of how to interpret it. Was there a drop in capital investment between 2008 and 2018? Did TFP, mysterious in itself, mysteriously vanished.

Meanwhile, the official labor productivity numbers are jumping up and down and all over the place. I have no idea what they are measuring.

With no regards to demand, would you rather employ:

-- 100% of available workers at a substantially lower productivity rate;

-- 75% of available workers for a superior productivity rate?