Yesterday I casually mentioned that I didn't think the overproduction of PhDs was a big problem. This produced some pushback, including the familiar complaint that it dooms lots of PhD-havers to a life of penury as members of the huge pool of adjunct professors desperately hoping they'll eventually land a full-time tenure-track job.

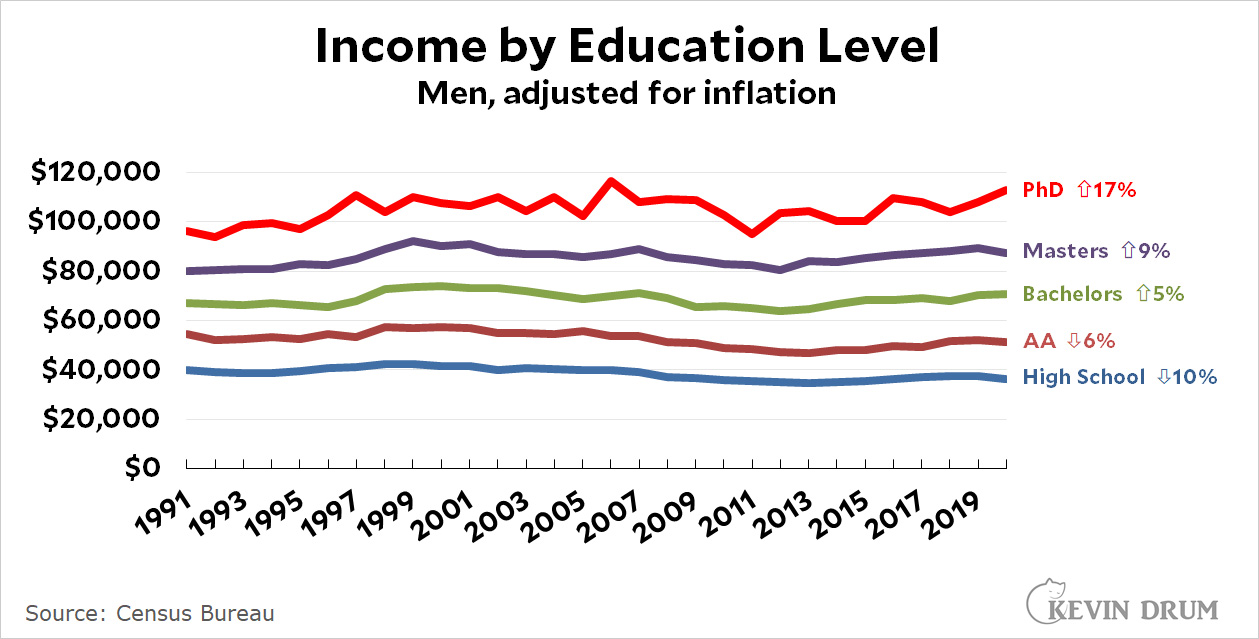

It's true that this happens, but it's due less to the overproduction of PhDs than it is to the steady decline of tenure-track positions in American universities. In fact, PhDs more generally are very well paid:

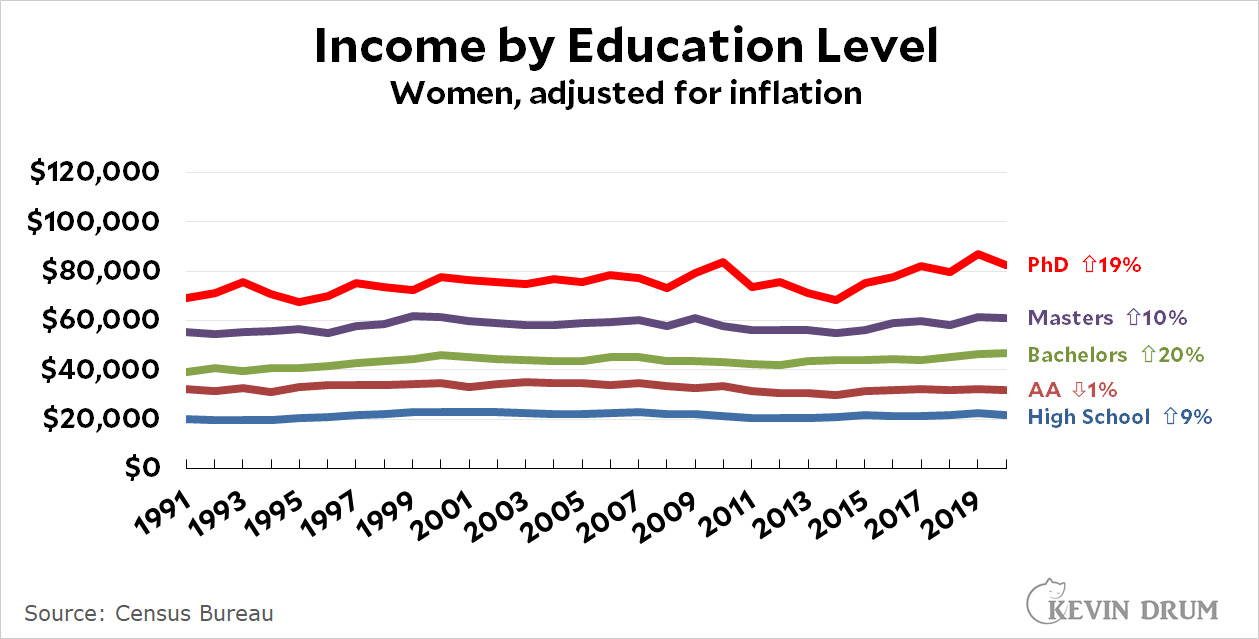

Not only is the median salary of PhDs quite high, but over the past few decades it's been increasing more than any other educational level. This trend is too persistent and too large to be the result of demand just for IT or just for STEM. Those might be the highest paid folks, but other PhDs must be seeing rising pay as well. This is strong evidence that, on average, there's no glut of PhDs.

Not only is the median salary of PhDs quite high, but over the past few decades it's been increasing more than any other educational level. This trend is too persistent and too large to be the result of demand just for IT or just for STEM. Those might be the highest paid folks, but other PhDs must be seeing rising pay as well. This is strong evidence that, on average, there's no glut of PhDs.

It's still possible, of course, that there's a glut in very specific areas. Maybe we mint too many PhDs in medieval European philosophy. It's also true that PhDs who are really committed to university teaching jobs are oversupplied. The lousy pay of adjuncts is evidence of this in the same way that high pay more generally is evidence of scarcity in the outside world.

So: are there too few full-time teaching positions in American universities? I would say yes. Permanent faculty is the lifeblood of a university, and it's appalling that this has been steadily hacked away in the name of budget cutting.

Is there a glut of PhDs who want university teaching positions so badly that they drive down pay for adjuncts? Again, probably yes.

But is there a general glut of PhDs? The evidence suggests there isn't.

This could be an episode of Big Bang Theory. Doctor Cooper, Doctor Hofstadter, Doctor Koothrappali, and Howard.

Howard got to go to space!

"but it's due less to the overproduction of PhDs than it is to the steady decline of tenure-track positions in American universities"

I think this is the correct answer.

I'm kinda past that age now, but a decade ago a noticeable fraction of my social circle was somewhere on the spectrum between agonizing over pursuing one, agonizing over dropping it, agonizing over their postdoc, or (in one case) celebrating her new tenure track gig.

The issue is a lot more people want to be professors than we apparently can support. (Another aspect of this that everyone wants to ignore: this drives the price of professors down.)

I'm a little surprised we haven't seen more of the same winner-take-all effects prevalent in sports, entertainment, etc. yet. Maybe it is just taking longer, but it isn't hard to imagine celebrity professors' lectures being syndicated between schools, them keeping their own stable of "teaching assistants" (probably more like producers and customer service), etc.

I generally agree with this and I have but one quibble:

I would write that as "...a lot more people want to be professors than we apparently want to support".

We are amazingly wealthy as a nation. We could support double tne number of professors if we wanted to, but we don't think it's important enough to do it.

I know this is a nit pick and probably what you meant, but I feel it's really important to distinguish between "can't" and "don't want to".

Excellent point. As a non-academic PhD myself, I find it discouraging that America has turned away from the kind of liberal education that America set world standards for in the 40's, 50's, 60's, and 70's. Since then it has been a slow slide downward for History, Philosophy, Art, Literature, Languages, and Music. These areas of study are now considered superfluous, though they were the foundation of Western education for a very long time. Instead, the public apparently wants college to be a vocational ed curriculum that leads to a good job.

Meanwhile, the ranks of college and university administrators has swelled like the toad in the fable, and the athletics coaches take home salaries that very few academics come close to. My state, Washington, makes its state employee salaries public information, available on the internet. Arrange the entries by salary and you see that there are multiple assistant coaches making $250 K, and head coaches making millions. Also vice chancellors of all descriptions.

America's STEM faculty are among the best in the world, and China sends hundreds of thousands of its best students to the US to learn our skills and systems and to eat our lunch. So long, America, it's been good to know ya'.

I agree completely. And the loss of the kinds of skills of thought, argument, & writing that the humanities enable students to master is significantly degrading our democracy.

Yes, and it's been that way for the past three decades at least--this isn't new.

For Universities without medical schools, the top salaries are usually the AD and coaches. For Universities with medical schools, the top salaries are usually the surgeons.

Not sure how valid this is, but I've also read that in recent decades there's been a marked increase in retirement age of tenured faculty.

UCLA recently posted a position requiring a chemistry PhD that had a salary of zero.

I am one of those PhDs that didn’t quite fit the academic system, but I’ve had a solid though erratic career path (I am now an iOS programmer).

While I used to think we produced too many PhDs, I think you are correct and that is only true if we are looking specifically at the academic market. However that is also largely how the entire PhD granting world operates. So, one improvement would be to acknowledge that not everyone is going to go into academia or into their industry specific training. It could help graduate significantly if there were a bit more emphasis at the institution level on helping graduates think about how to build a career that may or may not be specifically in their training, or just in investment banking…

It feels like there’s a lot of wasted food on the part of PhD‘s to figure out how to make things work. And I think a lot of times they do end up with a job that they got because of their academic rigorous training, whether or not it was subject specific. I guess what I’m saying is that graduate schools should make a very concerted effort to educate their smart but often exceedingly naïve graduate students about career development as a discipline.

I know that I left graduate school with a very specific, extremely narrow sense of what I was qualified to do. I think I could’ve benefited from a better sense that only half of us would end up with a career even within the broad range of our training, in my case Chemistry, rather than my youthfully naïve idea that most of us would actually be doing organometallic chemistry, though I allowed that a few of us might work on inorganic chemistry more generally. 🙂

I have no idea if there’s a good way to facilitate this or not.

"graduate schools should make a very concerted effort to educate their smart but often exceedingly naïve graduate students about career development as a discipline."

Spot on.

"I have no idea if there’s a good way to facilitate this or not."

One good way is for programs that do effective career counseling to advertise the successes of their graduate students outside of academic careers.

As a side note, the NIH training grant metrics measure output of graduates that end up in academic careers. If you have a significant number of grads who go into industry, your training grant won't get funded.

Regarding career development in grad school, my wife and I, both grad school survivors, have had many many very long discussions about how much we wish this would happen. But it won't. The people who run grad programs are the ones for whom the tenure track worked. They have no knowledge about the wider world of career options and have no incentive to care.

I'm sure that varies widely. Maybe more true in the humanities. But in the biomedical sciences PhD programs, there's a lot of support for careers in industry.

A real problem is that many faculty see going into non-academic positions as a failure that reflects on them.

That was certainly true 40 years ago when I got my PhD in genetics, and it's probably true in many or most elite humanities programs, but in the biomedical PhD programs there's a healthy respect for careers in industry. Of course, less than 25% of STEM PhD grads will land a tenure-track academic position these days.

You're deusioal if you think there is any possibility of 25% of STEM PhD grads will land a tenure-track academic position. The average professor at an elite institution graduates 50 or more PhD's over a career. Simple math tells you about 3 will get tenure positions, one replacing the professor and 2 others at non-elite universities. For professors at non-elite universities, they will graduate far fewer phDs but on average less than 0.5 of their students will land a tenure track position. (recall that their position is likely to be taken by a graduate of one of the elite institutions.

That's why I posted "less than 25% of STEM PhD grads will land a tenure-track academic position these days." Note the "less than" part.

BTW, I've been a professor at a research medical school for 35 years, have mentored seven PhDs and have served on dissertation committees for nearly 40 other PhD students. I'm on our faculty recruiting committee.

Back when I was applying for faculty positions (1986-97), many PhDs didn't land tenure track positions. Indeed, many went into industry back then, too. It has gotten tougher in academia, as research funding growth has slowed.

Also, when I entered the ranks of faculty, we were told that there would be a wave of retirements starting in ca. 2000, as the faculty hired during the 50s and 60s in response to the GI bill retired. Then, mandatory retirement of tenured faculty ended, and lots of geriatric tenured faculty held on.

Further, in STEM programs, a large share of grads are from China and India, and many are returning to their home countries. Not every US-trained STEM PhD is competing for US jobs in or out of academia.

Ultimately, the PhD is no longer a meal ticket (and hasn't been for over 30 years). Same with the JD. That said, the unemployment rate for PhDs in the US is still less than 2%, last time I checked.

I think this is pretty much right, but what it doesn't capture is which fields are now producing more or fewer Ph.D's. Over the past decade or so, many humanities graduate programs in particular have retrenched quite a bit, admitting and graduating fewer students so that their job placement numbers look better. But other areas like social sciences and STEM are definitely growing, due to demand from both academia and the private sector.

I talk to the previous generations and I just cannot understand why college used to be so cheap. Should do a deep dive on it

The short, incomplete answer is Baumol's cost disease.

No

At state schools the level of state funding was generally a LOT higher as recently as the 80's. GOP tax cut fever is at least a large part of the answer...

State school costs vary much more than you would think, depending on the state. I remember in the 80s when state schools in FL were cheap (they are still cheap but not quite so much as they once were) many of my dormmates were from MA, MI, and other northern states. For them the out-of-state tuition in FL was a lot cheaper then the in-state tuition in their home states.

People like to crack on the south but it is still true that our colleges are much, much cheaper to attend than the ones up north.

Just make sure they don't run into DeSantis' Purity Police!

Public universities used to be heavily subsidized by state tax payers. The elite public institutions forced the private schools to actually use their endowments to support education rather than simply to pay the administrators and to perpetuate their own existence

My total tuition and fees my first semester at UCLA came to $126, which apparently is worth $1134.87 today. Imagine getting a 4-year degree for under $10K. That was possible because the State of California thought it was good for the state to have lots of well educated young people around. Then the Vietnam War and Nixon and Reagan arrived and they despised "student radicals." The rest is ... no longer studied at universities.

The year was 1965.

The real cost of higher ed has gone up a lot faster than inflation, I'm pretty sure. So, while you're correct that US states (California included) have generally not maintained a strong commitment to defraying the out of pocket costs of tuition, it's also the case that emulating what was possible in the 1960s (in terms of out of pocket costs to families) would be vastly more expensive in 2022, even adjusted for inflation.

Someone mentioned Baumol's cost disease. That's part of it (just as with healthcare). But also part of it (also just as with healthcare!) is lack of top-down budgeting (known as "all-payer rate setting" in healthcare).

We'll never have such a system in the US when it comes to higher ed. Which in my view is a good thing: we mess with the country's glittering, world-leading constellation of prestigious universities at our peril.

But it obviously wouldn't be impossible to maintain publicly-funded post-secondary component that would enable all Americans who want a university education to get one without going into debt. And, again (!), similar to the situation with healthcare, we don't have the political will to do this.

In my view a national, federal-level response is necessary, both because a lot of our states are still living in the Middle Ages and show little interest in human development, and also because the incentive to robustly fund higher ed is limited when those receiving the education are obviously free to leave the state.

I looked at the NSF survey of PhDs web site. One thing I noticed is that starting salaries for humanities from 2013-2020 didn't keep up with inflation (down about 2% after inflation), while in CS/Math, the starting salaries went up by 17% after inflation over the same period.

I'm going to say that if an area's starting salaries are net declining, you have a glut of people in that area.

A far larger # of people in the humanities go into academia, compared to math/engineering, and the percentage of the latter going into academia has dropped a lot (from like 65% to 29%), while the percentage of humanities PhDs going into academia has dropped only a little, but from a high of 79% to 69% now, i.e. still very high.

So, people in the humanities are far more exposed to the difficulties of academic life than are math/engineering types.

But I doubt a PhD makes financial sense for either. For humanities, you're looking at a crappy salary after God only knows how many years of school.

For engineers, you're probably spending 4-6 more years in school than you would for a masters degree. That probably represents one or two opportunities to hit it big at a startup.

Is there a glut of PhDs who want university teaching positions so badly that they drive down pay for adjuncts? Again, probably yes.

There's also a glut of singers, actors, free lance writers and photographers.

Again and again Kevin makes the mistake

The only way to determine if there is a glut of PhD's is to examine how many "positions" there are versus how many PhD holders there are and compare both of those numbers to years past.

How many Boomers have PhD's?

For simplicity sake lets say there are 10 Boomer PhDs all employed. COVID causes 7 of them to retire - the university decides they can make do with 6 PhD level positions. 3 of those positions are occupied by CURRENT PhDs.

Are we over producing PhDs or limiting positions available?

Attaining a PhD is a stunning achievement and an investment of time. If, after investing all that time and effort you have a PhD but no one is hiring, yes we have a glut

IT and computer science are even less advanced degree oriented, so there's not a push in the field to go on to do PhD's unless you really want an academic/research focus. (Which is, IMO, a good thing.)

I would be surprised if the number of PhD's was growing much because the difficulty of getting good faculty positions has been pretty well known for a while now, unlike law schools a decade ago, where people were enrolling without realizing career prospects were getting much tougher.

I do worry about the decline of tenure and the overall struggles of academia.

Well, this is one of those instances where the analytical category "Phd" is probably not useful at all.

One almost certainly has very very different markets for PhD in most humanities (where there is little non-academic demand), versus PhD in various sciences, whether hard sciences / STEM or in soft sciences like economics and sociology etc where there can be important non-academic demand.

Given the really fundamental internal differences, it strikes me as rather unlikely that broad observations about PhDs in general can be usefully made.

"This trend is too persistent and too large to be the result of demand just for IT or just for STEM."

The overwhelming majority of Ph.D.s outside of academia are STEM, in fact scientists. The biggest employer by far of Ph.D.s is almost certainly the pharma industry. The statistics of average or median salaries is therefor dominated by the wages paid by that industry.

A Ph.D. in literature who works in a book store will be lucky to get a master level salary I would guess.

If there was a lot of pushback in the comments section I didn't see it. I think most people agreed with Kevin here.

Kevin mentions something about IT folks having PhDs. In my experience even a graduate degree is pretty rare in the IT sector. It's to easy to go straight from college, or even a coding boot camp, right into a well-paying full time job.

It should be pointed out that the source for the salaries by education is likely to be garbage. People with PhD's that are making little are likely to lie about their education level to cover their embarrassment. Fed income numbers often have very little correlation with cenus income numbers and I'd trust the fed a great deal more on money topics. And of course, the higher salaries that PhDs get probably has little to do with the PhD and the quiality required to get admitted into a PhD program.

"UCLA recently posted a position requiring a chemistry PhD that had a salary of zero." Research professor positions have always carried a salary of zero. You're supposed to raise your own funds and get your salary from that.

It was a teaching position. See https://www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com/2022/04/working-for-free-or-modern-life-in-higher-education

Why limit the discussion to PhDs? I bet there's also a glut of MBAs. If there's not a glut of lawyers, there soon will be. I know many young people with bachelors degrees who are driving taxis or working at supermarket checkouts.

Credentialism is a fact of life. American (and Australian) culture holds that "getting an education" is the pathway to a good job. As a general rule that's true, but the number of "good jobs" has held steady or even declined, while the supply of qualified candidates continues to increase apace.

The MBAs are worse because they rack up huge amounts of student loan debt in getting them. At least PhDs are (usually) funded programs for the people doing them, so all else fails at least they won't have a ton of student loan debt for tuition.

Remove the financial incentive and there is still "love of learning" and cultural/psychological rewards for higher ed. Dante and Cervantes and Shakespeare are a big step up from nearly all of the current best sellers. The Gilgamesh epic and Homer and Lady Murasaki even in translation are (as we used to say) mind-expanding. Get a PhD in English or History if you want to. Not all is lost if you eventually work in other vineyards.

But, of course, the financial incentive is a big consideration.

PHD=Piled Higher and Deeper

Speaking of PhDs,

bask in the iconic brainfulness of America's greatest hero and his definitive Vegas experience,

https://twitter.com/ryanjreilly/status/1512494884166504451

They'll be writing songs about this one day.

The real cost of higher ed has gone up a lot faster than inflation, I'm pretty sure. So, while you're correct that US states (California included) have generally not maintained a strong commitment to defraying the out of pocket costs of tuition, it's also the case that emulating what was possible in the 1960s (in terms of out of pocket costs to families) would be vastly more expensive in 2022, even adjusted for inflation.

Someone mentioned Baumol's cost disease. That's part of it (just as with healthcare). But also part of it (also just as with healthcare!) is lack of top-down budgeting (known as "all-payer rate setting" in healthcare).

We'll never have such a system in the US when it comes to higher ed. Which in my view is a good thing: we mess with the country's glittering, world-leading constellation of prestigious universities at our peril.

But it obviously wouldn't be impossible to maintain publicly-funded post-secondary component that would enable all Americans who want a university education to get one without going into debt. And, again (!), similar to the situation with healthcare, we don't have the political will to do this.

In my view a national, federal-level response is necessary, both because a lot of our states are still living in the Middle Ages and show little interest in human development, and also because the incentive to robustly fund higher ed is limited when those receiving the education are obviously free to leave the state.

Double post. Disqus, our nation turns its lonely eyes to you.

In fairness, I think a lot of PhD programs don't really prepare their candidates for the fact that most of them will likely not be full professors some day (or will have to become professors wherever they can get a job, even if it's somewhere they hate).

True, although this is getting better. While it is reasonable for a PhD-level student to possess the rudimentary curiosity to consider what path awaits them after graduation, mentors and programs at most universities could do a better job of placement.

Where then is the requisite chart showing said decline to be found?

"the steady decline of tenure-track positions in American universities."

What do the numbers say?

I see no such decline:

https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/csc

Is the argument supposed to hinge on technicalities of what counts as a tenure-track position? I don't see how that (desirable or not) is relevant to production vs consumption of PhDs. The number of teaching jobs has remained the same and I suspect that, more or less, the number requiring PhDs has remained the same.

But looking at the details I'm no longer sure who is arguing in bad faith or not.

The non-STEM PhDs have remained flat since the 1970s

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/12/03/survey-shows-annual-decline-number-phds-awarded

The STEM numbers look way higher BUT many of those (perhaps 40% or even more) are foreigners.

In a sense the diagram one wants is something like this

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-number-of-life-science-PhDs-awarded-annually-in-the-United-States-from-1985-to-2015_fig2_322962633

but even that diagram is set up to make a political claim, not for honesty (note again the number of PhDs is what is considered, not taking into account foreigner PhDs)

So I think I'm going to retire from this particular fight, concluding that pretty much no-one involved seems to prioritize a true understanding over an agenda, and I'm no longer interested in trying to figure out how any particular stat has been twisted.

A few years ago, I wrote an article on a logical oddity: adjunct positions are poorly paid, insecure, and require years of expensive education. k-12 teaching on the other hand, are relatively well-paid, secure, and requre a college degree and credential.

https://educationrealist.wordpress.com/2019/05/31/idiosyncratic-explanations-for-teacher-shortages/

Logically, adjuncts who are stuck teaching in lousy jobs should be more likely to consider moving to better paid teaching jobs, but in the main don't.

Please don't enumerate the reasons why they don't. I know them, the article goes through them, and the (excellent) commenters develop other reasons.

My point is not to wonder why they don't, but rather to show how their failure to do so puts the lie to two common beliefs about k-12 ed: 1) it's easy, and 2) the more academically qualified the teacher is, the better for outcomes.

That said, it's kind of dumb more adjuncts don't become 9-12 teachers. Pays much better, would alleviate teacher shortages, and ultimately be better for the adjunct market because universities would have to pay more to compete with k-12 schools.

They are very different jobs.

They are teaching jobs. There is a difference from tutor to k-12 teacher (with age differences there) to adjunct, but they're in the same family of job. And the idea that the difference is so huge that it's better to run around to different campuses for crap pay and no benefits than adjust is...well, look,I get it. Their egos won't tolerate it. But it's still pretty amazingly stupid in any objective sense. I understand the emotional devastation the decision would make.