How accurate are rapid antigen tests? It turns out this is actually two questions, one of them easy and one of them hard. Here we go:

What if a rapid test comes back negative?

If you conducted the test properly, then you almost certainly aren't infected at the time you took the test. Tomorrow, of course, is a different story.

What if a rapid test comes back positive?

This is the hard one. I'll spare you the math, but this depends on PPV, or Positive Predictive Value, which in turn depends on both the accuracy of the test and the prevalence of COVID-19—i.e., the number of people who are currently infected. When the prevalence of COVID is high, positive test results are more reliable.

I know: that's kind of weird. What makes it even trickier is that (a) you have to estimate prevalence and it changes over time, and (b) every state has a different prevalence level. In fact, you could do it down to the county level if you wanted. In general, though, even a pretty good test that has high sensitivity and specificity delivers surprisingly low PPV.

With that warning, here's a rough estimate of how reliable a positive test result is in areas with different prevalences of COVID:

- High: 40-60%.

- Medium: 20-40%

- Low: 10-20%.

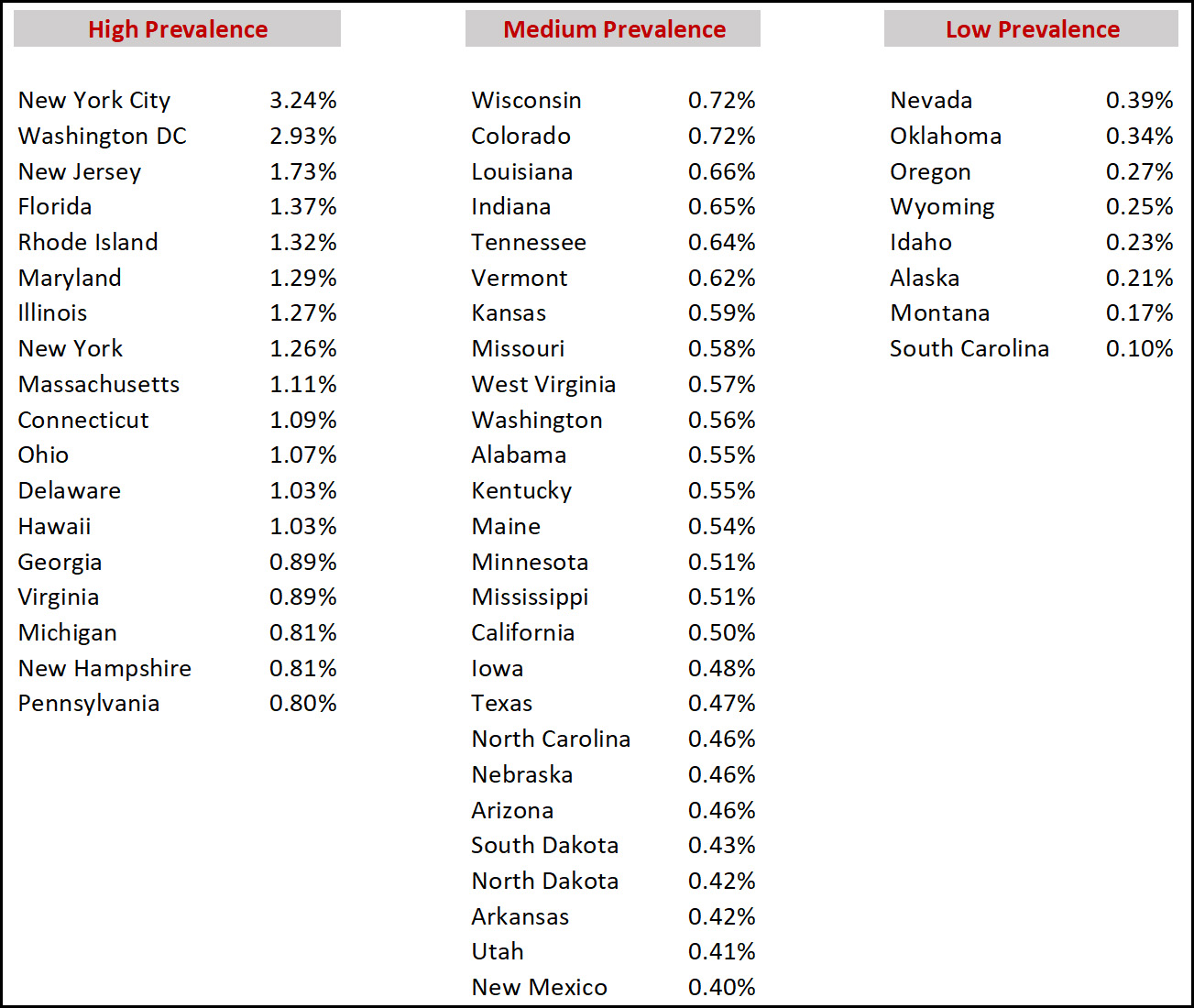

And here's an estimate of the current prevalence of COVID in each state. There's nothing fancy here. I just took the cumulative seven-day case rate and multiplied by 1.5 to get a measure of how many new cases had been reported over the past ten days. Since COVID seems to last about ten days or so, this provides a (very rough) estimate of the number of people who are currently infected.

Bottom line: Even in high-prevalence states like New York or Florida, a positive antigen result probably means there's only a 50-50 chance that you actually have COVID. In low-prevalence states, a positive result is next to useless. In either case, you should do another test in two days to check.

Bottom line: Even in high-prevalence states like New York or Florida, a positive antigen result probably means there's only a 50-50 chance that you actually have COVID. In low-prevalence states, a positive result is next to useless. In either case, you should do another test in two days to check.

Of course, also use common sense. If you have COVID symptoms—fever, cough, sore throat—then a positive result is much more likely to be accurate.

The Abbott BinaxNow test was studied in Pima County in Nov 2020. You can find the paper "Evaluation of Abbott BinaxNOW Rapid Antigen Test for SARS-CoV-2 Infection at Two Community-Based Testing Sites — Pima County, Arizona, November 3–17, 2020" on the CDC website. Test performance was quite good, but obviously it pertains to that point in time and the original Covid-19 virus. Abbott says its test continues to perform well on omicron. My reading of its Table 2 is that:

(1) if someone has NO symptoms, the test will identify 44 of 48 true positives = 92% success rate. In the same group, 4 of 2469 true negatives will get a positive result = 0.002% false positive rate. Also in the same group, if you test negative then the chances are 2465/2544 = 97% that you are truly negative.

(2) the results get better for people who display symptoms.

Not to flack for BinaxNow, but if results in the real world in the hands of consumers come close to these results, the test is very useful. We should be relying more on testing of this kind.

92% sounds about right. Given current prevalence of COVID, that translates to a PPV of 50% or less.

ummm...what???

from the article:

"Testing among symptomatic participants indicated the following for the BinaxNOW antigen test (with real-time RT-PCR as the standard): sensitivity, 64.2%; specificity, 100%; PPV, 100%; and NPV, 91.2% (Table 2); among asymptomatic persons, sensitivity was 35.8%; specificity, 99.8%; PPV, 91.7%; and NPV, 96.9%. For participants who were within 7 days of symptom onset, the BinaxNOW antigen test sensitivity was 71.1% (95% CI = 63.0%–78.4%), specificity was 100% (95% CI = 99.3%–100%), PPV was 100% (95% CI = 96.4%–100%), and NPV was 92.7% (95% CI = 90.2%–94.7%). Using real-time RT-PCR as the standard, four false-positive BinaxNOW antigen test results occurred, all among specimens from asymptomatic participants. Among 299 real-time RT-PCR positive results, 142 (47.5%) were false-negative BinaxNOW antigen test results (63 in specimens from symptomatic persons and 79 in specimens from asymptomatic persons)."

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7003e3.htm

In the asymptomatic sample described in Rincon Ranch's (1), the the PPV is (44 tp)/(44 tp + 4 fp) = 92% [same value as sensitivity, but that is just coincidence]. Prevalence is 48/(48+2469) = 1.9%, putting it higher than all but two locales in Drum's estimates. But that PPV is still significantly above the 40-60% range Kevin gives for high prevalence, so something is wrong somewhere.

Hmm. Most of the things I've read has given me the opposite impression, that a positive result means you most likely have Covid while a negative result is less certain due to the lack of sensitivity of the test. (My understanding is the at-home test is most effective when experiencing symptoms.)

Example of reading - https://www-nbcnews-com.cdn.ampproject.org/v/s/www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/rcna10227?amp_gsa=1&_js_v=a6&usqp=mq331AQKKAFQArABIIACAw%3D%3D#amp_tf=From%20%251%24s&aoh=16408905231595&referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com&share=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nbcnews.com%2Fhealth%2Fhealth-news%2Fneed-know-covid-home-rapid-tests-results-provide-rcna10227

As with most tests medical, you want it to err on the side of false negatives, not false positives. Especially since in these sorts of tests it's almost invariably the case there's a direct tradeoff between one and the other (Generally speaking, the tradeoff is around four-to-one. But that's talking about Beta, the parameter associated with the power of the test, and a whole 'nother story.)

Why on earth would you want it to err on the side of false negatives for a rapid test?

If it gives a false positive, that's inconvenient but can be resolved with a PCR test to confirm. A false negative means somebody who thinks they're clear and goes out to spread COVID.

Obviously you want to minimize any type of wrong result, but where there's a tradeoff, I want my at-home tests to make sure a negative is really properly negative, even if sometimes that means an incorrect positive.

You're right, of course. What I meant to say, and what I obviously did not write, is that Type I errors are to be preferred over Type II. My apologies.

There do seem to be different views on what the false negative rate is - just google "false negatives in rapid covid antigen test". There seems to be some evidence that false negatives are more likely with omicron. Kevin's "Almost certainly" may be 97% (see Rincon Ranch above) or less.

Anyway whatever the result from an antigen test, to be certain you should probably follow up with another test with a more accurate method (e.g. PCR), not just take another antigen test the next day.

Confirming a negative is pretty pointless. By the time the PCR results come back, they're days out of date--you could have caught or developed COVID in the meantime.

The main point of at-home tests is to make sure you don't have COVID before going to a social event, traveling, etc. For that to work, you want to test as soon as possible before the event--within an hour or two if you can. If it's positive, you stay home and schedule a PCR to confirm. But if it's negative, you go do the thing.

If everybody who goes to a major event with promiscuous intermixing involving a couple of hundred people tests negative beforehand, but there is a three percent chance that each of them is really positive, there is a good chance it could be a superspreader event (depending also on how many are vaccinated). So if the false negative rate is really this high (which seems to be possible) maybe such events are not protected by everyone being tested and should be prohibited. There are really a lot of variables involved in determining the significance of the tests. It would be very good to have a rapid test that has lower rates of both false positives and negatives.

Kevin’s postt is a very confused (and confusing) attempt to describe Bayesian reasoning.

Skeptonomist, in your comment in this sentence—“ If everybody who goes to a major event … tests negative beforehand, but there is a three percent chance that each of them is really positive, there is a good chance it could be a superspreader event”—you have ignored Bayes. If x% of the population is Covid free, and if the rate of false negatives is 3%, then the expected rate of infections that slip through the testing will be

R = 0.03 * (1-x%).

If, for example, the population has contains 4% infected persons, then

R = 0.03 x (1-0.96) = 0.0012

So if there are 200 people in attendance, and they all test negative, then the expected number of infected persons would be approximately 0.24.

This means that, for the parameters specified, there would be a 99 3/4% chance that there were no infections among the 200 tested attendees.

You're right. The paper https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7003e3.htm says that there are essentially no false positives (negative people who test positive). If there are no false positives, a positive test means you're sick.

Kevin should have gone farther and spoken of precision vs recall. Or as I used to ask back in the day when I taught basic stats "Given that the pregnancy test is 95% accurate, what do you do when it comes up positive?" The girls were invariably the first to answer -- and to answer correctly -- 'Take another test.'

What specificity value are you using to calculate the final numbers, Kevin?

Doing a quick Google search, I found an NIH publication giving a specificity for antigen tests of 0.999, and a sensitivity of 0.44 (for asymptomatic individuals).

Plugging that into the PPV formula, and using my home state of TN with your estimated prevalence of 0.0064, I come up with a PPV of 74.3%.

This is one of those times when you really should have shown us the math, Kevin.

Formula: PPV = (sensitivity * prevalence) / ((sensitivity * prevalence) + ((1 - specificity) * (1 - prevalence)))

I also suspect your estimates of prevalence are low by a factor of 2-3 for the medium/low areas given the exponential rate at which this is spreading.

Good man. Why oh why don't they teach this stuff as a matter of course in high school?

"Why oh why don't they teach this stuff as a matter of course in high school?"

It's hard to do when you are learning math on an abacus. Like I did

Heh. We had to use Greek numerals. And we were thankful!

chiseling into marble...

'More than one rabbit' was the biggest number we had.

“estimates of prevalence are low by a factor of 2-3”

I don’t know anything. I’ve seen really high estimates from models showing 1 in 10 currently infected in London (a few days ago), and 1 in 20 currently infected in San Francisco. I think the models assume certain asymptomatic case levels (given the age, predicted vaccination status of the likely cases, prior exposure levels?) testing propensity/availability, etc…

I haven’t seen many prevalence surveys done, in the US. None with the new variant obviously. Lots of moving parts…

I think 5% for SF might be a little high, or it might be low. Maybe 1% for the country. 5% in one week implies 20 weeks at the current rate. Feels kinda plausible. I think I believe it.

By”survey” I mean randomly sampling people then extrapolating/adjusting to the population.

As opposed to waiting for people to test themselves, whatever their reasons might be (symptoms, a potential exposure, requirements for work/school/travel). Then these results getting reported. (How are home self-tests reported?)

We seeing 0.2% of the population testing positive per day (200 new cases per 100K). If you go with the disease lasting 10 days, then you are, or will be, at 2% of the population being positive, 1% if you use 5 days. The tricky thing is that not everyone is tested, nor is the testing population a random sampling, so we have to guess how many people are actually infected per reported infection. That can be a high number when a lot of the cases are mild or asymptomatic. If you use a factor of 5, then you're looking at 5 to 10% of the population being infected when the reported new case rate is 0.2%. (200 new cases/day per 100K, and if that rate holds for 5 to 10 days).

For DC, ca. 1 in 7 people currently infected

NY (state), NJ and PR: 1 in 10 (1 in 20 if use 5 days for the course of the infection)

RI, FL, IL, MD, MA, CT: 1 in 15

OH, DE, HI, GA, PA, MI, VA. LA: 1 in 20.

There's a lot of hand waving in this--but the results are not unreasonable. Projections of 10% of the population being infected currently in some areas is realistic.

The (1-specificity) term in your PPV computation is 1-0.999 = 0.001.

So, you've miscomputed the PPV, which is .44*.999/(.44*.999 + .9936*.001) = .44/(.44+.001) = 99.77%

Sorry, I screwed up this computation by using specificity instead of prevalence.

Swab your throat there matey...

https://slate.com/technology/2021/12/throat-swab-rapid-testing-omicron-effective.html

Like it really matters. Testing for coronavirus is pretty irrelevant now. It will pass through society like ice cubes melting. Then by January 20th, fading from history.

Cases will fall off, but hospitalizations will linger...

And it matters for schools starting up.

First, the basic premise of Kevin's post makes zero sense . There is no reason on earth I can think of that the prevalence in the community will make a positive test more likely to be correct, as an independent variable.

What I think is going on here is that there is a certain percentage chance that a person who is really not infected will still create a false positive. Say that % is X. The chance your positive test is a false positive is going to depend on the chance that YOU , the person getting tested , is infected ( before you get tested). And what I think Kevin is doing, or really relating what others are doing, is using the estimated prevalence in the community as a proxy for the chance that YOU the tested person, are infected.

But why do just that. Better to start with maybe the prevalence based just on confirmed cases ( i.e. do not try to guess at multiple to get actual infections) and estimate your personal chance of being infected vs the average chance of those being tested . After all, if you are being tested , then you are in that group and those who are never tested should be irrelevant. But then you might also need to adjust for those who never report their positive test and just stay home .

One thing I expect if at home tests become common is positivity rate should increase significantly even if a really no change. Those thinking they might have a small chance of having covid and test at home. If it is negative, they do nothing and never reported. If positive, they follow up with a pcr test. This subtracts out all those who would have had a reported negative pcr test if that was only option.

Although I do not think it matters if you analyze it correctly as above, I do think Kevin's 1.5 factor for estimating actual infections is way too low today. I think we might have got below 2.0 at times but not much. And , today, with more asymptomatic cases with omicron and , presumably, a greater chance of a false positive pcr test, plus some current difficulty with testing availability, the multiple is almost surely much higher.

Also, the 10 day presumed infection period is too high . With symptomatic delta , still might be a touch too high on average. Including onicron and asymptomatic, definitely lower .

And should also consider what TYPE of false positive.

Lumping them all in together is flawed.

I have researched this much for

Damn it , this comment system gives me problems. Too quick post again.

So did not research this with rapid test but did with pcr early on as arguing with covid sceptical thinking all the positive pcr tests were hugely false positive.

So consider three types of false positive.

One is a true false positive where it gives a positive without any virus or part thereof at all. This was extraordinarily low for the pcr test ..and that is proved by the very very low positivity rates in places like new Zealand when they had almost no cases. And positivity rates here in places like ny dropped to very low levels too in very low case periods. If pcr true false positives were say 1.0% , that would be a floor for positivity rates but it was not . For pcr , true fajse positives rare enough to be a non factor.

Then there is a mistaken person false positive test . Say getting a pcr test and you are not infected at all. But the person in the next car being tested is. And, by chance, some of that persons virus drifts over in an air current and gets on your test. The test itself worked fine and detected the virus ,,and found an infection. It just was not yours .

Then there is the chronological false positive. You were infected a month ago but asymptomatic . And now are no longer infected. But pieces of the dead virus are going to be in your body for months and the pcr test reacts to them . Note the pcr test does not actually test for the live virus itself..it reacts to parts of the virus .

Then there is the false positive due to human error where there is no test issue . Such as the lab losing a test but covering it up by just reporting it as a positive. I know one person whose wife was supposed to get tested with their son ( who had to for school) . She could not make it so he took their son. And asked if he could use her appointment since already there. One person logged him in but then they said no, cannot take her spot . Days later, result came in that son's test was positive. And they reported him as positive test too although he never got tested!

With rapid test, I presume likeiy a true false positive is much more likely than pcr. But I would guess the other types are less.

And the effect of the false positive depends on for what . A chronological false positive, where it picks up the remnants of a past infection, is aok for overall reported case numbers. And also aok to show that the person had natural immunity. But bad in showing if currently infectious.

A specific example may help.

Assume a population of 1000. 100 people have COVID.

If you have COVID, the test will say positive 95% of the time.

If you do not have COVID, the test will say positive 5% of the time.

So of the 100 people who have COVID, 95 will test positive. (95% of 100)

Of the 900 people who do not have COVID, 45 will test positive. (5% of 900)

So 140 people test positive.

Your probability of actually having COVID is 95/140=68%.

Even though the test is 95% accurate

So Mr Bayes—You’re posting here under the name “Velcro?”

Actually, Velcro, I tip my cap to your elegantly concise explanation-by-example.

Conditional probability does not imply Bayesian, you knnow. What he's giving you is just bog-standard pedagogical tree analysis.

I think Kevin's 1.5 was a conversion factor between a 7 day cumulative value and the 10 days that someone stays sick.

Ah.

Yes, you are probably right now that I reread it. Not sure why kevin did not just multiply by 1.428 then to get it right as that is as easy. If he had done that, I would have seen it, I think.

Of course that means kevin is defining prevalence only based on confirmed cases , and not including cases ( most of asymptomatic) never confirmed. Which , as I explain above, might be really better for this purpose of inferring the probability you have covid . But only if YOU match the average of those getting tested.

Most places tested consist of three groups . Those with covid like symptoms, those who know they were exposed to someone with covid, and those who have no symptoms but are tested for school work, randomly, etc.

And the proper inference should be from positivity rate only for your category of tested. Unfortunately, I have not seen anyone reporting positivity broken down this way.

Note kevin mentions that, if you ate having symptoms , then that is a reason you should up the chance the test really is positive from his initial guess. But to balance that , the opposite should be true. If tested randomly with no symptoms , you should decrease the chance that a positive test is true . And the relative reduction or increase on chances depends on the relative proportions of those who are being tested.

With Omicron it can change in an afternoon not a day.

If you have sympthoms and test positive you are almost certainly infectious. Everything else is probabilities.

Sorry Kevin, but you've got this completely backwards. The CDC says that Binax, for example, has a specificity of essentially 100%, and a sensitivity (for asymptomatic people) of 36%.

Specificity is the percentage of people who are negative who get negative results. Assume that 98% of the population are healthy and 2% are sick. The 98% healthy all get negative results. Of the 2% sick, 0.7% get positive results and 1.3% get negative results.

So, the only source of positive test results are the 2% who are sick, i.e. a positive test means you're sick, period.

A negative result means you're either part of the 98% who are healthy or the 1.3% who are sick but the test missed (because they're probably not contagious yet). So, a negative result means that the odds are 98/(98+1.3) or 98.6% that you're healthy. But mostly that's because only 2% of people are sick, and if you chose someone at random, they're probably healthy.

One other point: by the definition of sensitivity, if you're sick, the odds that the test will catch you is only 36%. So, the test isn't particularly useful at guaranteeing that sick people won't pass and interact with other people. However, Binax-like tests apparently (I heard on the street) fail primarily before you're actually contagious, so a recent negative test probably means you're not contagious for a little while longer.

Here's a link to the CDC's page with BINAX's stats: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7003e3.htm

Play with this: https://kennis-research.shinyapps.io/Bayes-App/

If you're vaccinated, unless you're symptomatic AND positive, forget about it and live your life.

And if you test positive with rapid antigen test, always confirm it with a 2nd test a day later (if symptomatic, repeat negative test too to be sure, especially if unvaccinated).

Basically, you shouldn't really be getting tested unless you're symptomatic or directly exposed to someone who is symptomatic AND positive (and I wouldn't bother getting tested in this latter case either, unless unvaccinated).

In the U.K., rapid antigen tests have been routinely used for screening on asymptomatic people, and the government has issued transparent reports giving the percentage of these tests that are confirmed by PCR. The most recent one I could find is for the week Nov. 25 to Dec. 1 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1039633/rapid-testing-9-december-2021.pdf). In that week, when cases were less prevalent than they currently are here, about 90% of positive rapid tests were confirmed by PCR.

The bottom line: Kevin's estimates are almost certainly totally wrong, unless our antigen tests are much less specific than the ones used in the U.K. If you test positive with a rapid test, even with no symptoms, it is very likely you have covid.

It seem to me that the "accuracy" of the test depends on the question you are asking. If the question is, "am I infectious right now", a PCR may give you a false positive if you are newly infected and aren't shedding virus yet. It may also give you a false positive on the back end, when you're still infected but have ceased shedding virus.

If the question is, "are these symptoms I'm starting to feel really covid", then if you really have Covid, that may mean that the level of virus is above the sensitivity threshold of both the antigen test and the PCR test and they are equally accurate.

Anyway, the only question that the studies of test sensitivity/specificity answers is, "does this test match the results we get with our gold standard PCR test." Not quite the question the consumer is asking.

Another question you might be asking is, "have I been exposed to Omicron but am not yet infectious, but will become so soon." Omicron becomes infectious soon after exposure, let's say 3 days. Let's say a PCR test registers positive 1 day after exposure, and an antigen test starting 2 days after exposure. In this case, the PCR test is only useful (or more useful than antigen) if you take the test between 1 and 2 days after exposure and you get results within 1 day. Otherwise, it's no better than an antigen test.

The PROBLEM, is this

What will YOUR employer accept as proof that you need to quarantine for 5 days? An at home test or one provided by an independent 3rd party.

We all know the answer to that one............

Kevin's calculation only applies for use as a *screening* test. It assumes people being tested are effectively a random sample from the population so that prevalence is a good estimate of a testee's prior probability of being infected. I think it would be important to clarify this.

I assume people choosing electively to test would have a higher prior probability of being infected than the prevalence in their community, but I have no idea how big that effect would be.