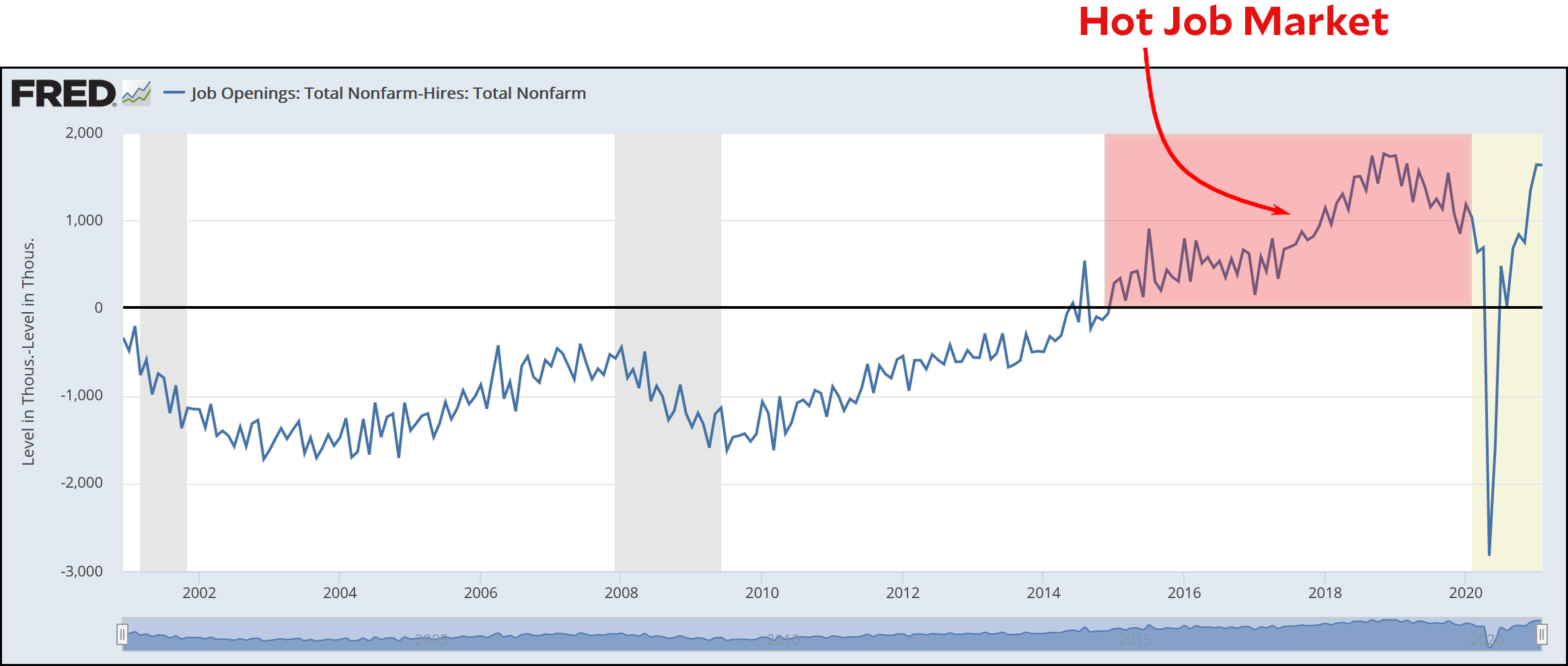

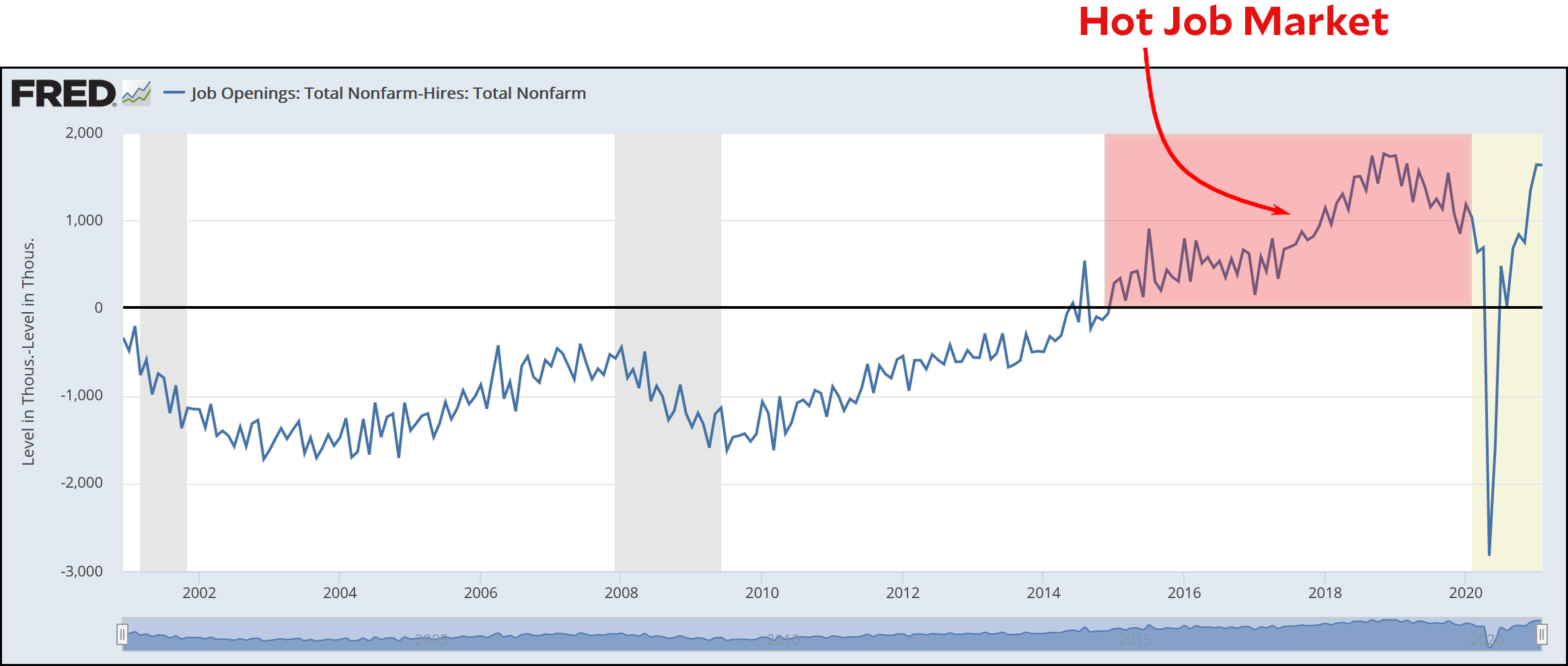

Here's an odd thing about today's jobs numbers. If you take a look at job openings vs. hires, you get a chart like this:

A job only counts as an official "job opening" if an employer is "actively recruiting" for the position. In normal times, and during recessions, there are plenty of workers to go around, which means there's little need for active recruiting. As a result, official job openings are low and there are fewer job openings than hires.

But if the economy is running hot, companies have lots of job openings they can't fill. This means they start actively recruiting and the job openings get counted. That's what you see in the shaded red area. Starting around 2015, the economy started hitting on all cylinders and there were more job openings than hires. In 2019 things started to slow down a bit, and then the pandemic hit and jobs disappeared.

Anyway, starting last September the difference between hires and job openings began to widen steadily until it hit nearly 2 million, which is where it was at its high point pre-pandemic. So that means the economy is doing well and employers are eager to hire more workers. Hooray?

Maybe, but now we view things differently. Back in 2017, the fact that companies wanted to hire more people than they could find was a good thing. It meant the labor market was tight and workers would get paid more. Today, it means . . . what?

- The labor market is tight because there are lots of people who are afraid to go back to work while COVID-19 is still loose.

- The labor market is tight because many women with children can't find childcare and are staying out of the labor force.

- The labor market is tight because workers are figuring they'll use up their unemployment benefits before they bother getting a job.

- The labor market is tight because employers are being stingy about pay and benefits. In April, average hourly earnings actually went down compared to a year ago.

All four of these are plausible reasons. In fact, all four of them could be true at the same time. We just don't know. But only if we get an answer will we have any idea whether the labor market is truly in good or bad shape.