The New York Times, echoing the views of most liberals, says the Supreme Court is dismantling democracy piece by piece:

The latest blow came Thursday, when all six conservative justices voted to uphold two Arizona voting laws despite lower federal courts finding clear evidence that the laws make voting harder for voters of color — whether Black, Latino or Native American. One law requires election officials to throw out ballots that were cast in the wrong precinct; the other bars most people and groups from collecting voters’ absentee ballots and dropping them off at polling places.

This is starting to piss me off. Maybe the Supreme Court is bound and determined to take apart our voting laws no matter what, but the truth is that yesterday's ruling can be laid directly at the feet of liberals. This was just a stupid case to bring. You can't make a serious argument that there's anything really wrong with either a ban on ballot harvesting or with requiring voters to cast ballots in the right precinct.

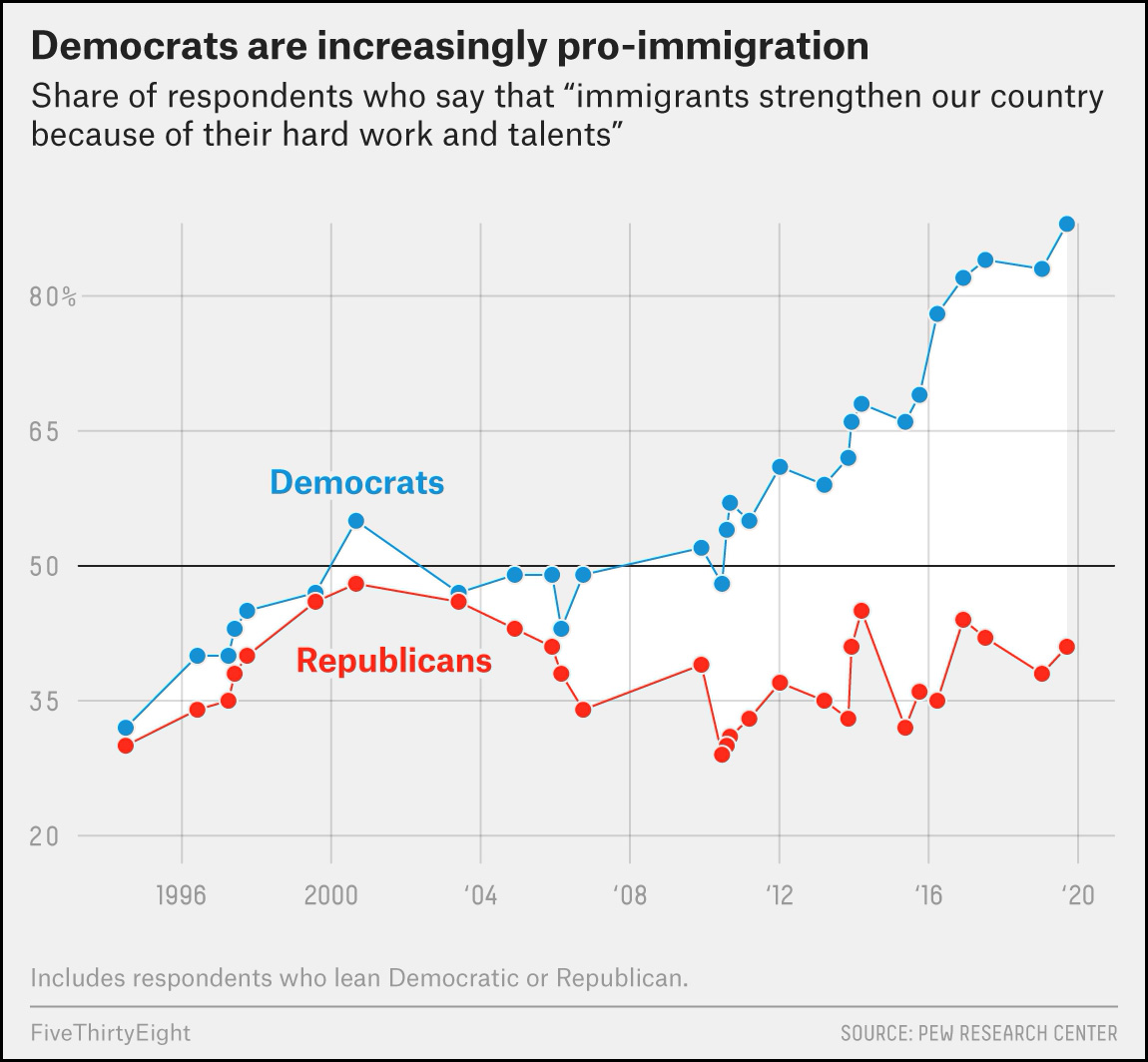

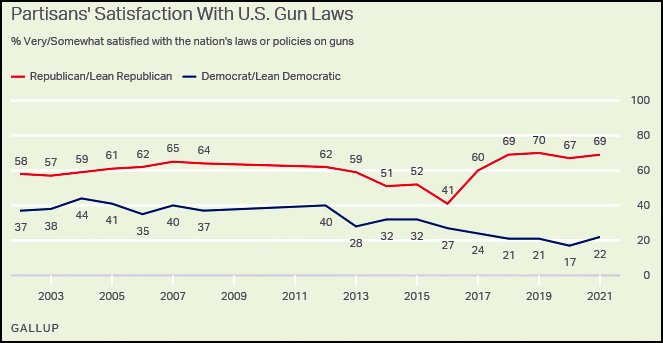

More generally, this kind of stuff, along with voter ID laws, is popular with the public, and this has nothing to do with the alleged existence of voter fraud. Even if there's no fraud, the average Joe and Jane think ID laws make sense and are untroubled by common sense rules like being required to vote in the right precinct. Liberals will get nowhere by going after this stuff.

What's more, none of it matters. The actual effect of these rules on Black and Hispanic voter turnout turns out to be minuscule. It is a waste of time—maybe worse than just a waste of time—to yell and scream about these kinds of laws.

What really is bad are provisions of these laws that allow Republican legislatures to replace election officials they deem insufficiently loyal to the Republican cause. If you talk to moderate voters, they'll be shocked if you tell them about this. They'll agree that these provisions are outrageous.

So why do we spend so much time protesting the stuff that doesn't matter (and is popular) and so little time protesting the stuff that does matter (and is unpopular)? It is a vast mystery. And like I said, it's really starting to piss me off. If democracy is truly at stake here, wouldn't it make sense to be at least a little smart about trying to save it?