The Guardian regales us today with yet another article about the shortage of truck drivers:

Truckers say the problem isn’t a shortage of qualified drivers; there’s plenty of people who have been through the training programs and hold a commercial driver’s license. The rot, they say, is far more systemic: low pay, long hours and an industry that treats drivers like “cannon fodder”, churning out new recruits who inevitably quit because the job is so grueling.

“There is no driver shortage; there’s a retention problem,” said Mike Doncaster, a 30-year veteran and driver trainer who parked his big rig at Joe’s Travel Plaza for the night, before heading up to Canada with another load of vegetables.

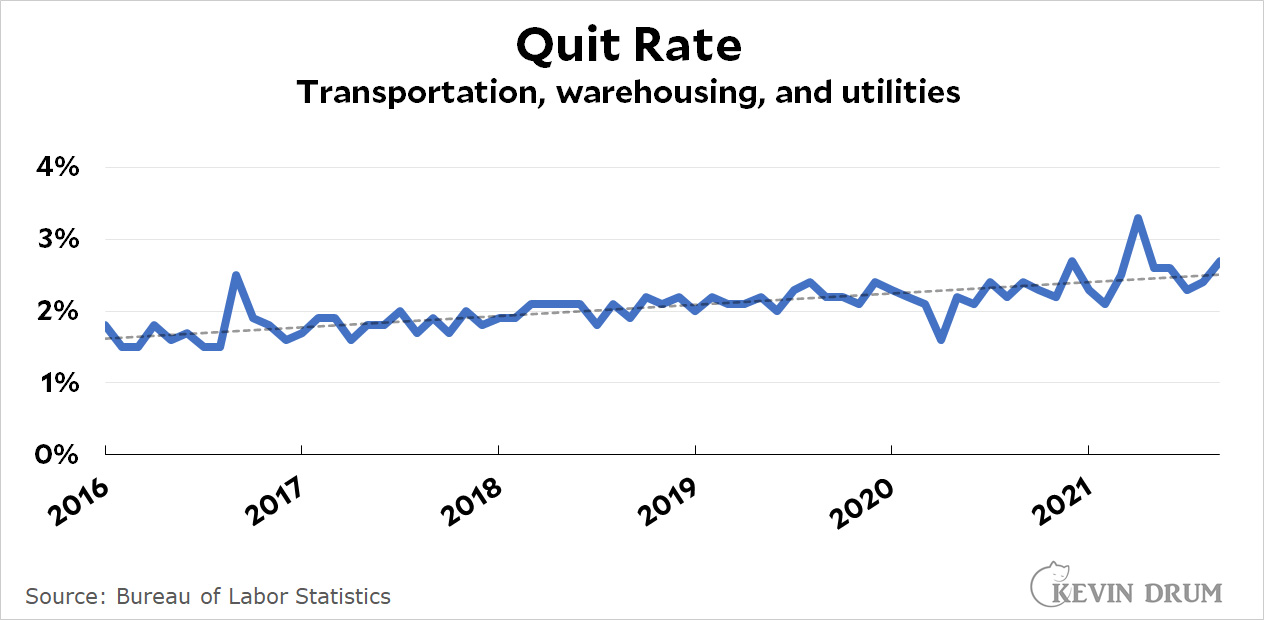

I don't doubt that long-distance trucking is a pretty crappy job these days. But are truckers really quitting at higher rates than usual? Unfortunately, that's hard to say with the data we have at hand. Here's the quit rate:

Nothing looks out of whack in the most recent months, but the data for quits uses pretty broad categories. In this case, it's all transportation, plus warehousing and utility jobs.

Nothing looks out of whack in the most recent months, but the data for quits uses pretty broad categories. In this case, it's all transportation, plus warehousing and utility jobs.

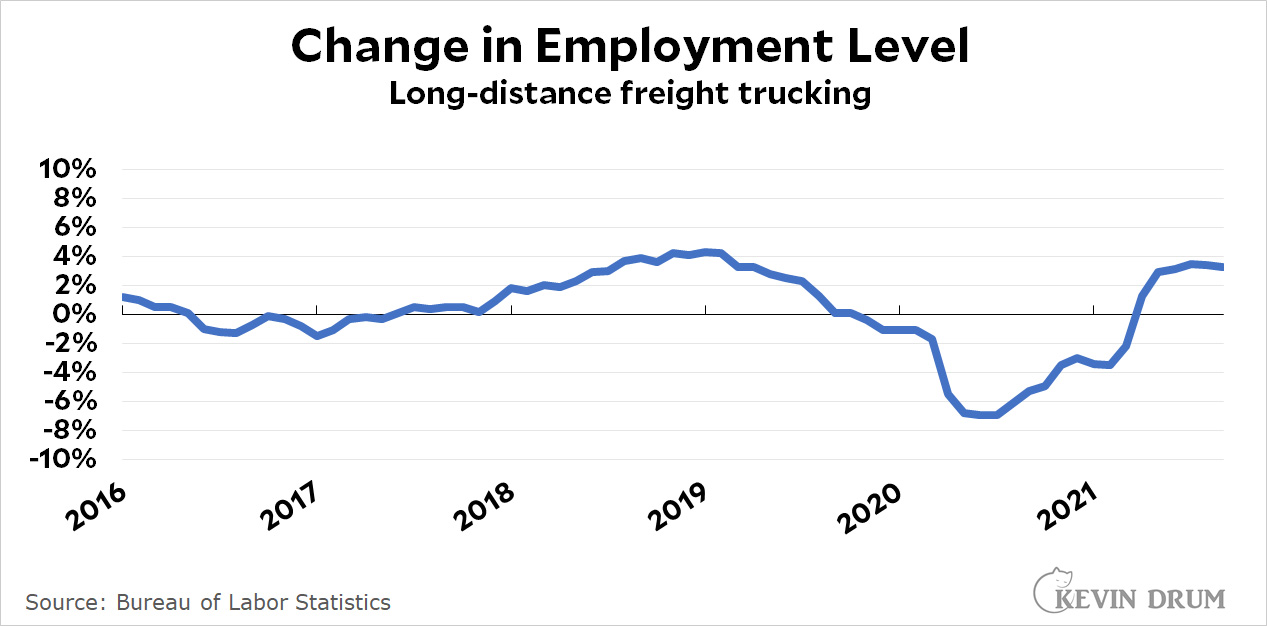

We also have this:

The absolute number of long-distance truckers is within a percent or two of where it was before the pandemic, and employment is rising at a rate of more than 3%.

The absolute number of long-distance truckers is within a percent or two of where it was before the pandemic, and employment is rising at a rate of more than 3%.

So we have one series that shows quits, but only broadly, and another that zeroes in on long-distance drivers but only shows employment levels. If you put them together I think the obvious interpretation is that nothing new is happening right now. Quits are probably no higher than historic levels, and the number of drivers is increasing solidly. What's more, long-distance driving continues to pay about 25% better than other blue-collar jobs.

To put things simply, we don't have a trucker shortage, we have a goods surplus. In an economic sense I suppose you can say they're the same thing, but given that the goods surplus is almost certainly temporary it hardly seems likely that trucking firms want to hire a lot more permanent drivers who they won't need six months from now. They're hiring as many truckers as they think they need and they don't seem to be having a lot of trouble attracting them.