This is a large neon artwork celebrating booze at the Grand Central Market in downtown Los Angeles. If anybody can provide some background about what inspired it, let us all know in comments.

Cats, charts, and politics

All three men involved in the murder of Ahmaud Arbery have been found guilty. All things considered, this has not been a bad week for the criminal justice system.

Household spending regained its pre-pandemic level earlier this year and has continued to grow since then at about the same rate as it did before the pandemic. Adjusted for inflation, spending was up 0.7% in October compared to September:

The news is not so cheery on the income front. Adjusted for inflation, personal income has been declining since July and declined again in October by -0.3% compared to September:

The news is not so cheery on the income front. Adjusted for inflation, personal income has been declining since July and declined again in October by -0.3% compared to September:

How long can spending hold up if income is declining? That all depends on whether households still have savings stashed away from all the stimulus bills. But they don't:

How long can spending hold up if income is declining? That all depends on whether households still have savings stashed away from all the stimulus bills. But they don't:

My prediction: With savings back to normal and real income declining, spending is going to flatten out too. This might not happen until after the holidays, but unless something changes I suspect January will be the start of a pullback among consumers. Supply chain problems will be largely under control by then too, which suggests to me that inflation will also start coming down.

My prediction: With savings back to normal and real income declining, spending is going to flatten out too. This might not happen until after the holidays, but unless something changes I suspect January will be the start of a pullback among consumers. Supply chain problems will be largely under control by then too, which suggests to me that inflation will also start coming down.

This is just my layman's guess, of course. We'll see.

In the New York Times today, Rogé Karma fills in for new dad Ezra Klein by interviewing sociologist Patrick Sharkey about crime and what we can do about it. Here's the introduction:

In 2020 the United States experienced a nearly 30 percent rise in homicides from 2019. That’s the single biggest one-year increase since we started keeping national records in 1960. And violence has continued to rise well into 2021.

To deny or downplay the seriousness of this spike is neither morally justified nor politically wise. Violence takes lives, traumatizes children, instills fear, destroys community life and entrenches racial and economic inequality....Liberals and progressives need an answer to the question of how to handle rising violence.

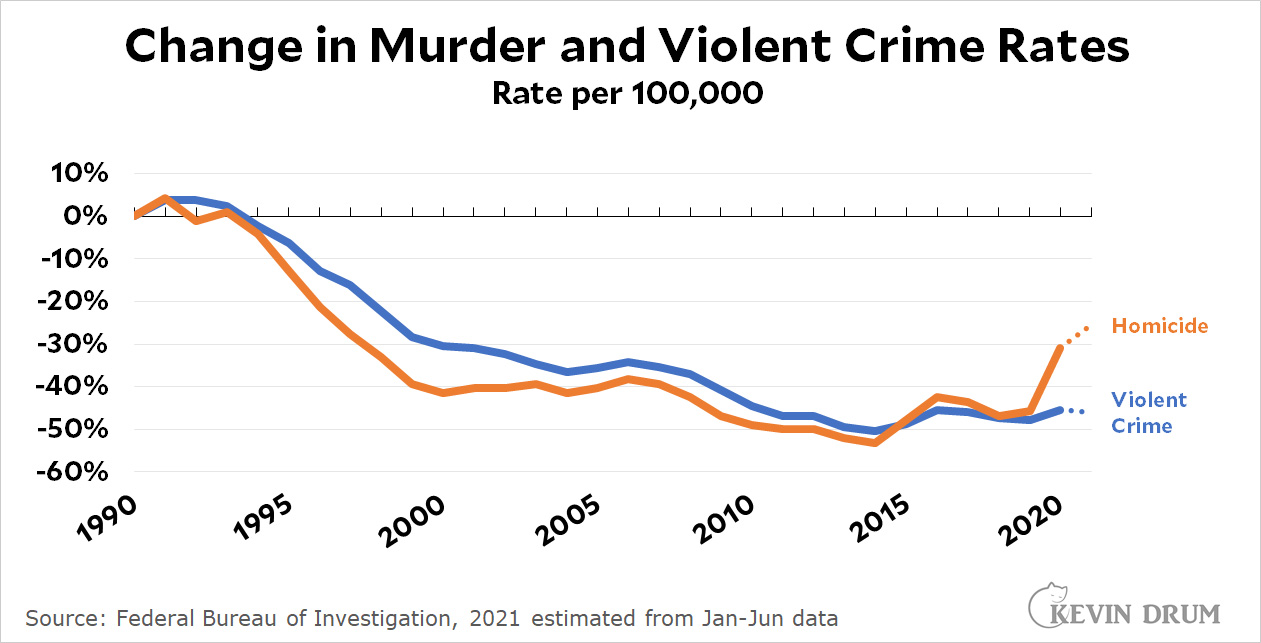

This language is a little fuzzy, so I just want to remind everyone that the real mystery has to do not with murder and violent crime, but with murder versus violent crime:

As you can see, for 30 years the murder and violent crime rates have changed almost precisely in unison. Then, in 2020, they suddenly diverged. The big question, then, is why did murder rates spike so high even though the overall violent crime rate remained steady?

As you can see, for 30 years the murder and violent crime rates have changed almost precisely in unison. Then, in 2020, they suddenly diverged. The big question, then, is why did murder rates spike so high even though the overall violent crime rate remained steady?

This is not the topic of the interview, which is about how we can reduce urban violence via methods other than policing. It's very much worth reading, but it's also worth keeping in mind that overall violence hasn't changed much over the past decade. Only the murder rate has. This is something that deserves some careful study.

Today we have four different photos showing the interior of St. Peter's Basilica. From the top:

Which one do you like the best?

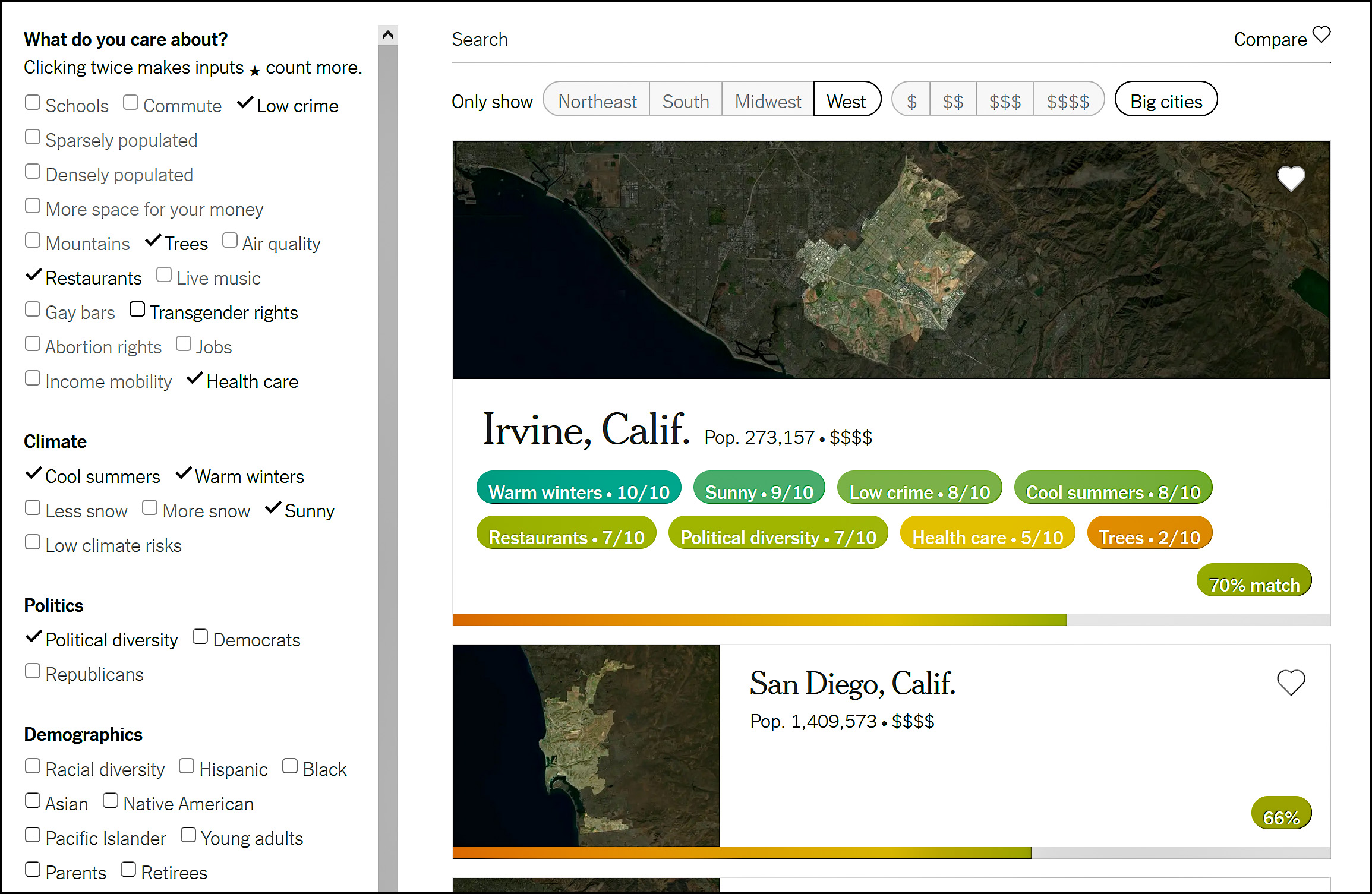

It took a bit of doing, but I finally found the set of inputs that provided me with the correct answer on the New York Times's "Where Should You Live" clickbait thingy:

This took a while. At first it kept telling me I should live in New Jersey. Then I restricted it to the West and it told me I should live in various tiny towns in northern California. Then I restricted it to big cities and up popped Irvine. Hooray! Moving is such a pain in the ass.

This took a while. At first it kept telling me I should live in New Jersey. Then I restricted it to the West and it told me I should live in various tiny towns in northern California. Then I restricted it to big cities and up popped Irvine. Hooray! Moving is such a pain in the ass.

Oh ffs. Dollar Tree says it is now $1.25 Tree:

The company — one of America's last remaining true dollar stores — said Tuesday it will raise prices from $1 to $1.25 on the majority of its products by the first quarter of 2022. The change is a sign of the pressures low-cost retailers face holding down prices during a period of rising inflation.

I'm whistling into the wind, but I have two comments about this:

Question: Will our media report things this way? Or will they use this as a hook for "high inflation claims another victim" stories? Sadly, I suspect I know the answer.

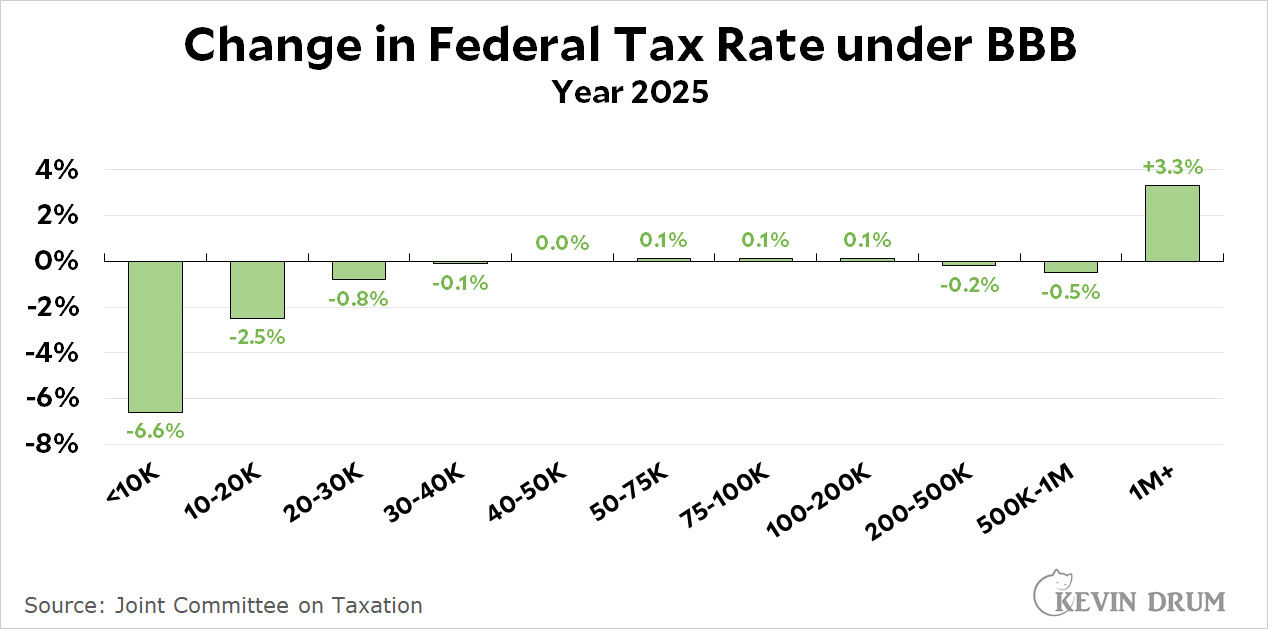

Will you pay higher or lower taxes under Joe Biden's Build Back Better bill? The Joint Tax Committee has the answer:

This is in 2025, when the tax provisions have pretty much all kicked in. It's not clear to me why we want to lower taxes on the $500K crowd, but this is all of a piece with the rest of the bill. It's well intentioned but generally seems to be kind of sloppy in execution.

This is in 2025, when the tax provisions have pretty much all kicked in. It's not clear to me why we want to lower taxes on the $500K crowd, but this is all of a piece with the rest of the bill. It's well intentioned but generally seems to be kind of sloppy in execution.

A while ago I asked if there were any academic types who had written a good summary of all the research about the impact of social media on teenage users. At least, I think I did. Maybe I only thought about doing it, because I can't find it now. [Ah, here it is.]

In any case, it turns out that Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge have been compiling a list of research papers on this subject for the past couple of years. This prompted Haidt to write a piece for the Atlantic titled "The Dangerous Experiment on Teen Girls." This article is very specifically about Instagram, not social media in general, and his argument goes approximately like this:

By itself, this is not the most persuasive argument I've ever read. However, we can learn more by looking at the Haidt/Twenge list of research papers.

First off, they found 29 studies that showed an association between social media use and teen mental problems. They also found 11 studies showing no association.

This is moderately persuasive, though a 72% hit rate isn't conclusive. A bigger problem is that the studies almost all found that effects kicked in only among teens who used social media a lot (4-5 hours per day or more). This immediately raises the question of whether (a) social media causes mental health problems or (b) teens with mental health problems seek out social media more obsessively.

This is an obvious question, and in a separate section Haidt and Twenge highlight studies designed to test causality. Most of them are experiments where teens are asked to eliminate (or cut back) social media use for a few weeks. At the end of the experiment their mood was compared with that of a control group that made no changes. Of the 13 "true experiments" they found, eight showed a causal effect and five showed no causal effect. This is suggestive, but even less conclusive than the association studies.

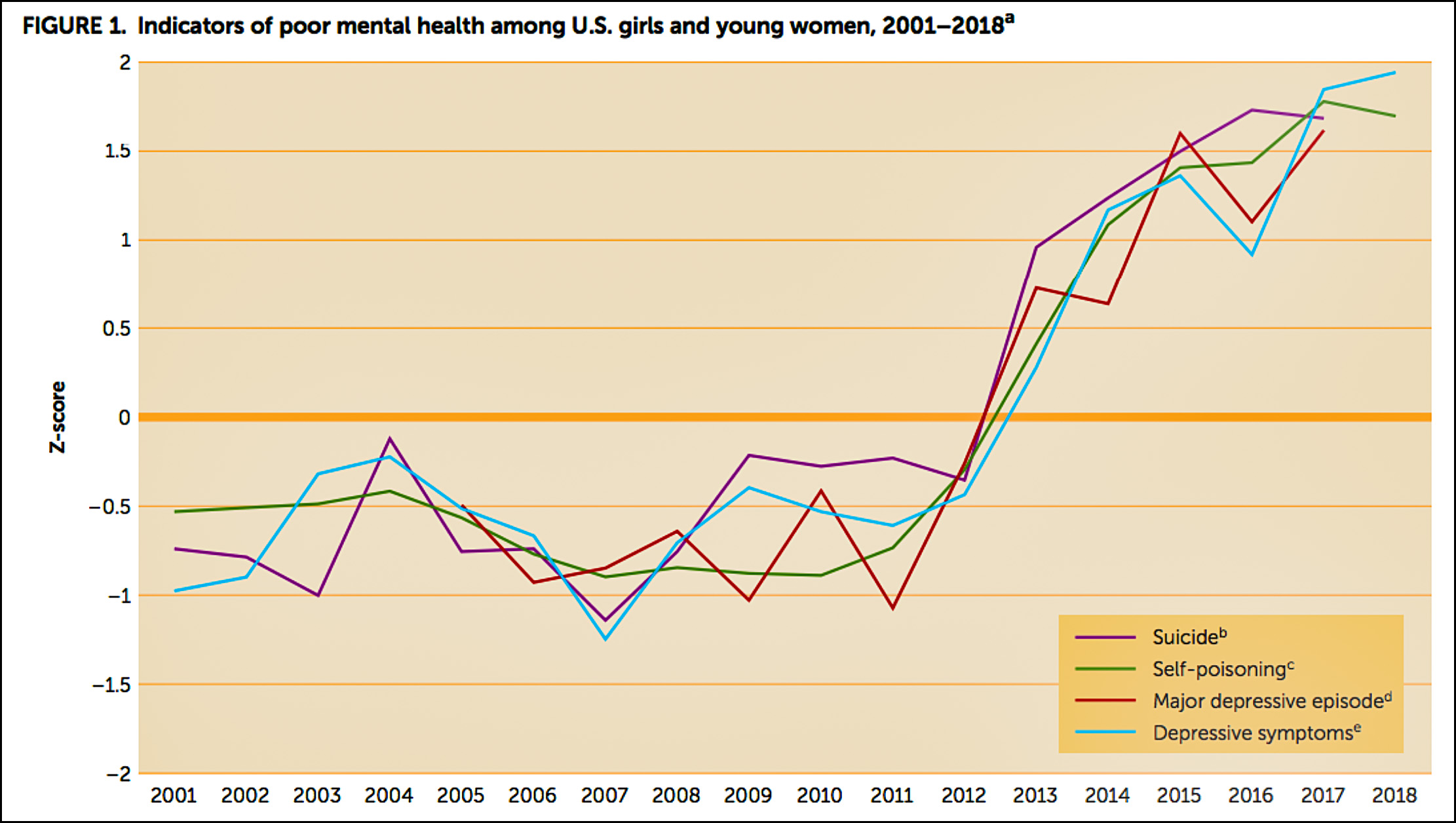

Overall, I'd call this moderately weak evidence. I also had a couple of other problems. This chart, for example:

This shows an astonishing jump in mental health problems between 2011 and 2013. It hardly seems possible that anything could cause such a huge spike in a mere 24 months, and certainly not a mere 10-20 point increase in the number of teens using social media. This makes me wonder if there's some kind of artifact in the reporting of mental health problems.

This shows an astonishing jump in mental health problems between 2011 and 2013. It hardly seems possible that anything could cause such a huge spike in a mere 24 months, and certainly not a mere 10-20 point increase in the number of teens using social media. This makes me wonder if there's some kind of artifact in the reporting of mental health problems.

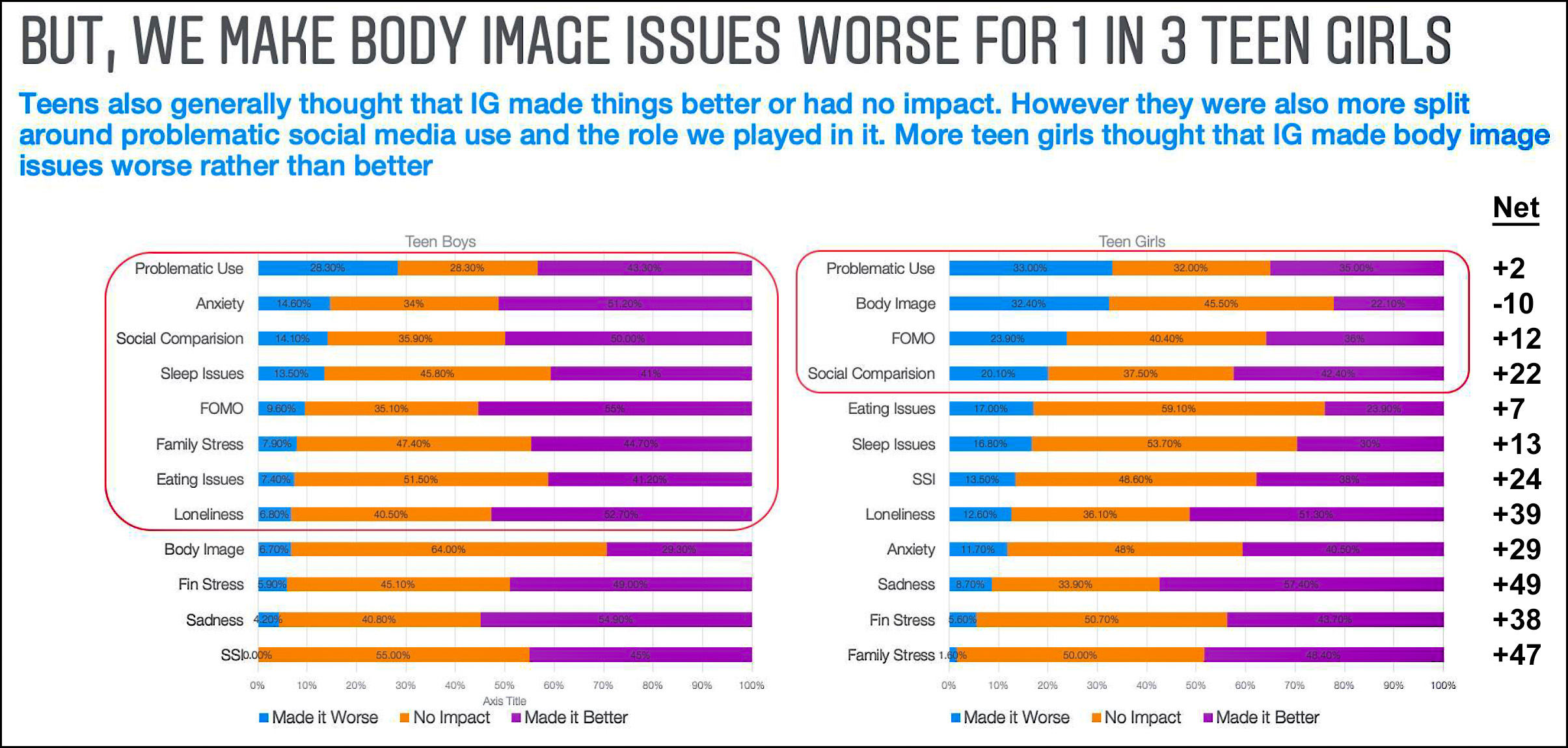

My other problem was Haidt's reference to the recently leaked Facebook documents as support for his thesis. But as I've pointed out before, there's no there there:

Among teen girls, Instagram has a net negative effect on one thing (body image) and a net positive effect on everything else. This simply doesn't support the argument that Instagram is an overall problem for teen girls.

Among teen girls, Instagram has a net negative effect on one thing (body image) and a net positive effect on everything else. This simply doesn't support the argument that Instagram is an overall problem for teen girls.

All this said, there's enough evidence here that it certainly suggests some caution is probably in order. And as it turns out, Haidt makes three proposals that are suitably cautious in turn. First, he wants social media companies to allow academic researchers access to their data. Second, he wants the age of "internet adulthood" to be raised from 13 to 16. Finally, he wants to encourage a norm among parents and schools of delaying use of social media until high school. None of these strike me as objectionable given the suggestive evidence we have.

Obviously research on social media and mental health is difficult to do well. Nevertheless, if we're going to act responsibly instead of moving straight to our usual panic phase, we need something better than what we have now. In particular, we need a more thorough explanation of what happened in the 24 months between 2011 and 2013. Beyond that, we need higher quality studies of how social media affects teens, ideally using something better than self-reported hours of internet use (which is highly unreliable) and self-reported survey questions of mental health (also not terribly reliable). Let's get cracking, researchers!