Ezra Klein says the public has lost faith in the ability of the government to build big things:

A key failure of liberalism in this era is the inability to build in a way that inspires confidence in more building. Infrastructure comes in over budget and late, if it comes in at all. There aren't enough homes, enough rapid tests, even enough good government web sites.

....There's both a political and a substantive problem here. The political problem is if people keep watching the government fail to build things well, they won't believe the government can build things well. So they won't trust it to build....The substantive problem, of course, is that we need government to build things, and solve big problems. If it's so hard to build parklets, how do you think that multi-trillion dollar, breakneck investment in energy infrastructure is going to go?

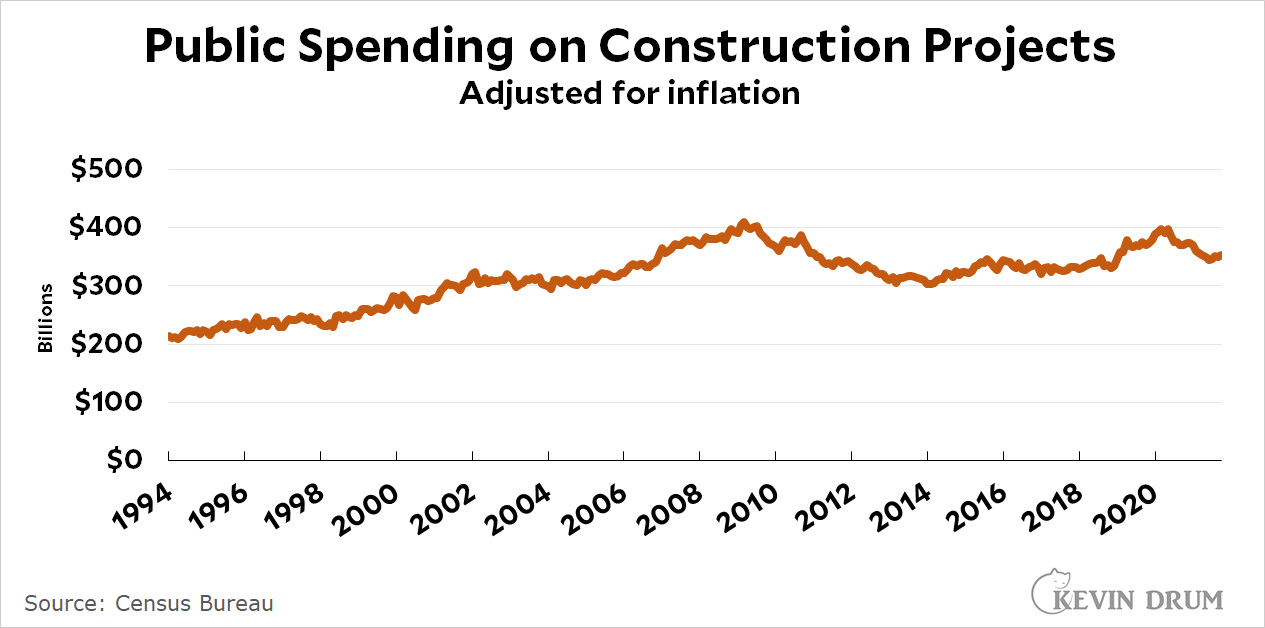

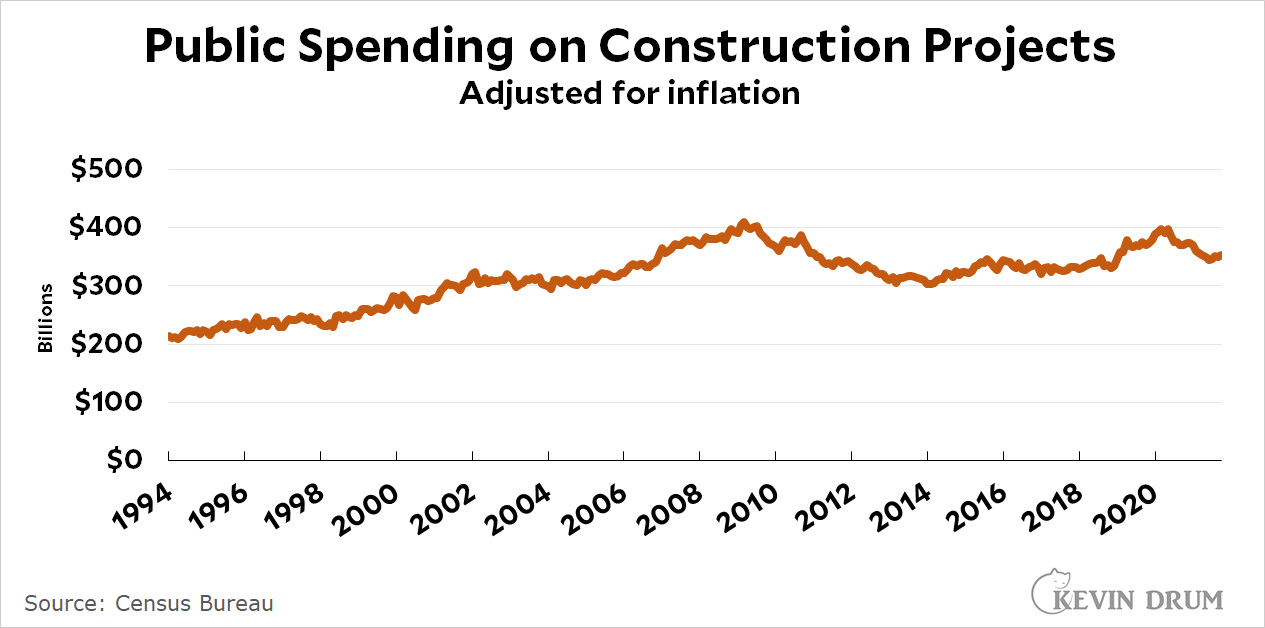

Ezra naturally wants to solve this problem, since building big things is a key part of the liberal project. But first, it's worth taking a look at whether it's really a problem in the first place. Here is spending on public construction projects:

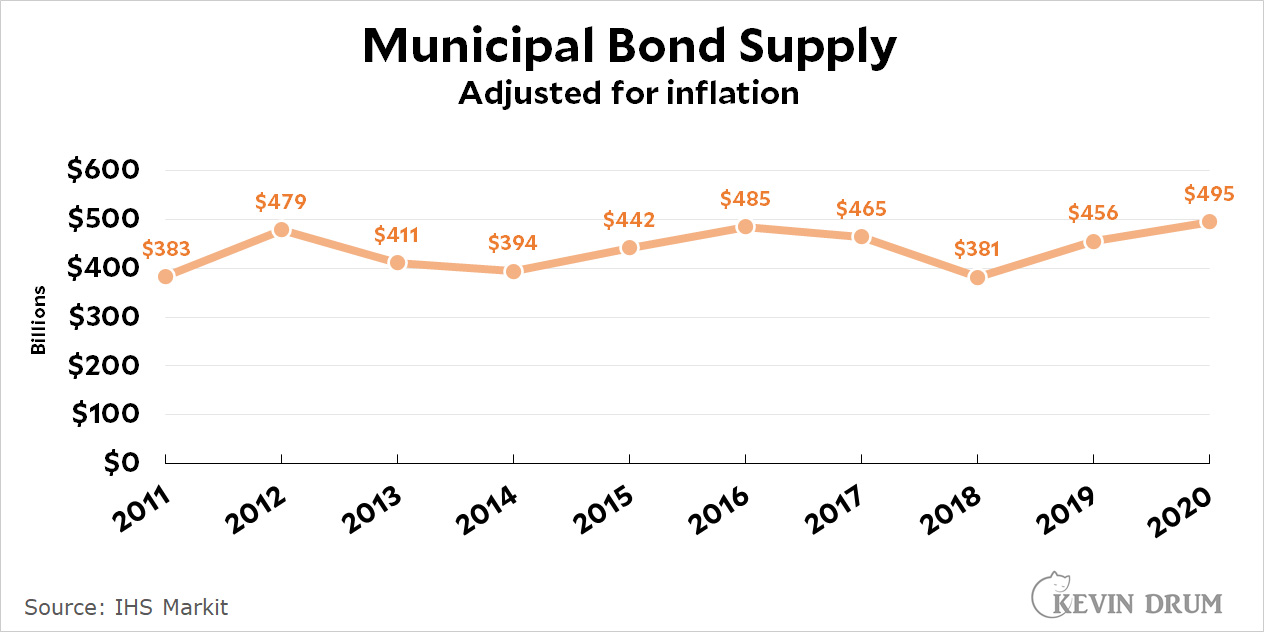

There's no sign of a decline in public construction. Here's a look at municipal bonds:

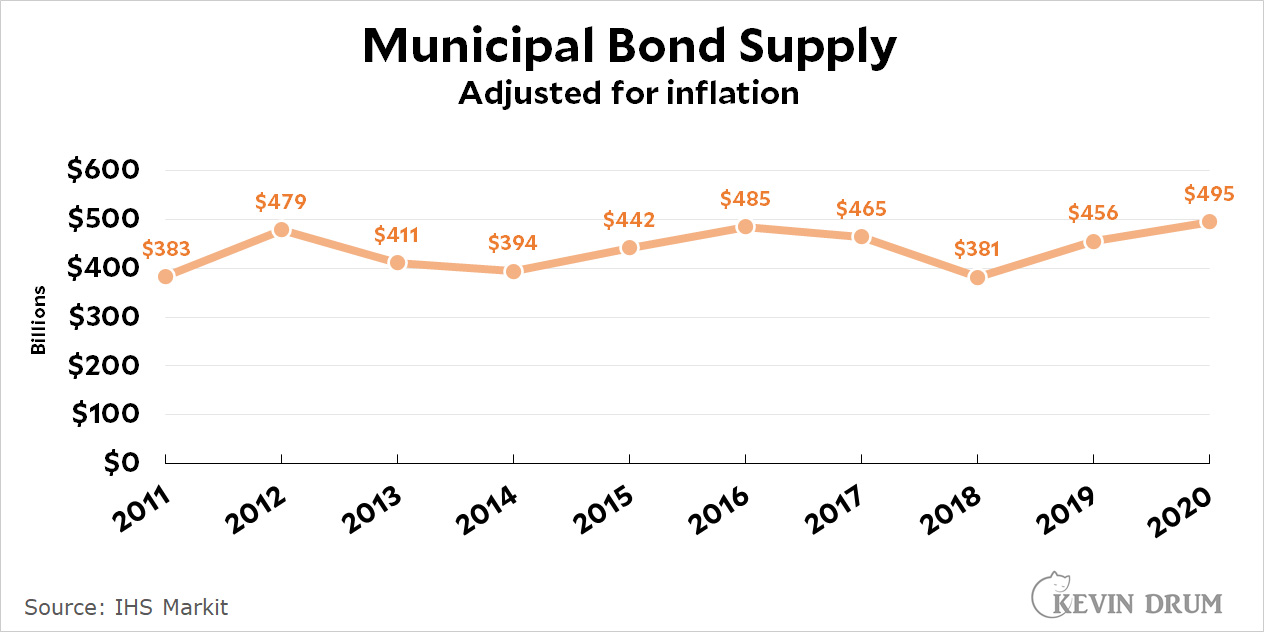

There's no sign of a decline in public construction. Here's a look at municipal bonds:

Muni bonds are used to fund public works, and the supply of these bonds has been steady over the past ten years. IHS Market estimates that $28.7 billion worth of muni bonds were on ballots in last month's election, about average for the past decade, and that 65% of them were approved.

Muni bonds are used to fund public works, and the supply of these bonds has been steady over the past ten years. IHS Market estimates that $28.7 billion worth of muni bonds were on ballots in last month's election, about average for the past decade, and that 65% of them were approved.

This is just a couple of pieces of evidence, but it's enough to make me think it's at least worth investigating whether the public really has lost faith in the ability of government to build things. I suspect not.

If I'm right, it exposes an odd paradox: As we know, trust in government is way down, but trust in the ability of government to build stuff is perfectly steady. My own county is an example of this. Orange County is famously skeptical of big government, but in 1990 we approved a half-cent sales tax increase to fund transportation projects. In 2006, a whopping 70% of voters re-approved it. OC voters might be skeptical of government in general, but the one thing they do approve of is spending money on asphalt and concrete in ways they can see with their own eyes.

There are always big-ticket fiascoes around to grab the headlines. In California we have our bullet train to nowhere. In New York City, the Second Avenue subway is a long-running punch line. But consider the real lesson of these projects: even though they are gigantic disasters, the public continues to support them. Isn't that remarkable? As long as the project is something people actually want, they are willing to put up with almost anything.

On the other hand, if it's something they don't want, they will find an endless barrage of excuses not to allow it.

I suspect that this is the real lesson to be learned. Trust in government to build things hasn't changed. The only thing that's changed is what liberals want to build. If we can convince the public that our ideas are good ones, they'll support paying for them. If not, they won't. Maybe that sounds too simple to be true, but not every problem has to be complicated.