Here is Brian Stryker, a Democratic pollster who worked in the Virginia gubernatorial race:

What was the first thing you told your partners after you got done with the groups — what was your big takeaway?

I was surprised by how dominant education was in this election. I was also struck by how much it was this place for all of these frustrations for these suburban voters, where they could take out their Covid frustrations in one place.

....How do Democrats balance a commitment to core constituencies while at the same time addressing economic issues that voters are confronting every day?

The No. 1 issue for women right now is the economy, and the No. 1 issue for Black voters is the economy, and the No. 1 issue for Latino voters is the economy. I’m not advocating for us ignoring social issues, but when we think broadly about voters, they actually all want us talking about the economy and doing things to help them out economically.

Wait a second. Was the dominant issue in the Virginia election education? Or was it the economy? Only one can be the #1 issue.

One of the most consistent results in political science is that bad economies are bad for incumbents. It's not even a matter of voters explicitly blaming anyone in particular for bad times. It's just that bad economies make people unhappy, and unhappy people generally figure that a new face might be worth taking a chance on.

That's uncontroversial. What's less obvious is whether incumbents stuck with a bad economy can do themselves any good by talking about the economy. I'm pretty sure the answer is no. I mean, what can an incumbent say?

- "We're working hard on it." That just makes you sound ineffective.

- "We need to make big changes." So why haven't you done that already?

- "The economy is better than you think." Makes you sound out of touch.

- "We'll get through it." Makes you sound like you're doing nothing.

There's really no good message. The best thing an incumbent can do is change the subject and hope for the best. After all, Ronald Reagan didn't win a landslide reelection because of his happy talk on the economy. He won a landslide reelection because the actual economy was booming by 1984. Lucky guy.

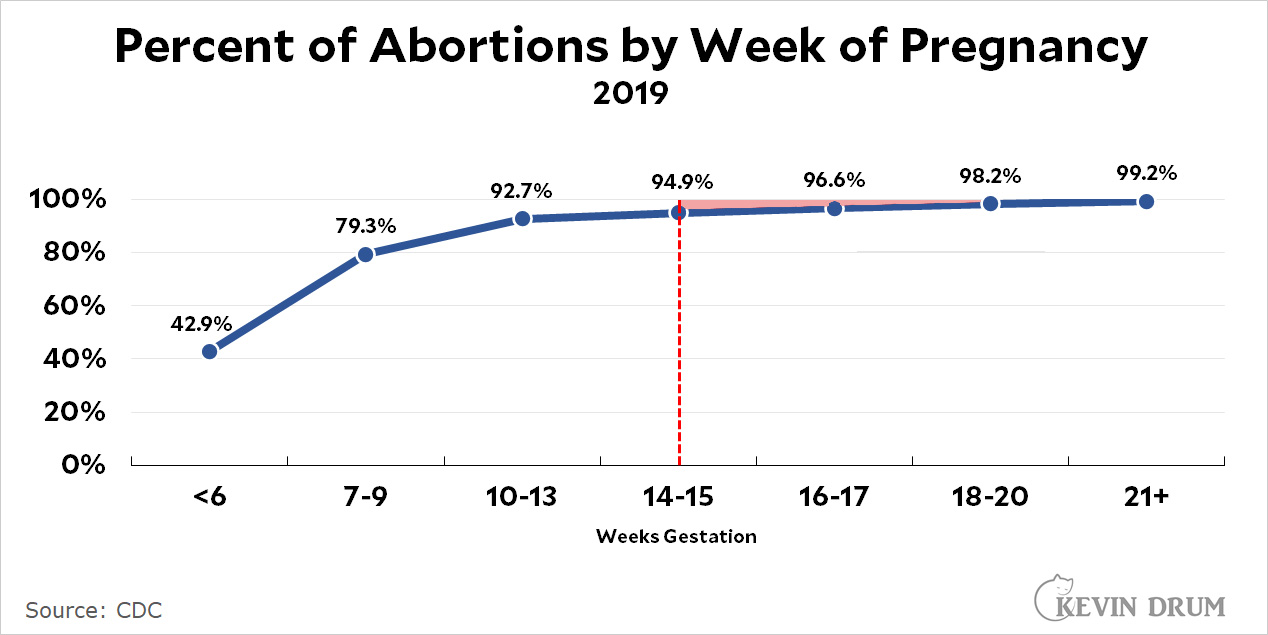

The good news for Democrats is that the economy is frustrating right now, but it's not all that bad. Doom isn't inevitable. So what should Democrats do? I'd say that's obvious: Do just enough talking about the economy so they sound like they care, but otherwise find some high-salience culture war issue they can talk endlessly about. The key here is to find some issue where Republicans are on the unpopular side. Unpopular. OK?