A few days ago I wrote that we should stop "blaming everything on social media." I based this on the fact that research just doesn't seem to back it up. Social media isn't all strawberries and clear skies, but overall its effect seems to be mostly neutral or even moderately positive.

But research is hard to do in this area and it's usually years behind anyway. So when a longtime reader sent me a different perspective, I figured it was worth posting to give the other side of the story. Here it is.

I'm a longtime reader and appreciate your work. I became—and have remained since—a daily visitor to the site starting when I lived in Chile as a college student two decades ago, when your writing was a connection to home.

Since then I've gone on to teach, coach, and be an administrator in public high schools in Oregon and earned my master's and doctorate in education. I've worked through the years of mass adoption of cell phones and deployment of social media.

I've read in multiple pieces—most recently in your ten worst trends post—where you've stated we need to stop blaming social media for ills because it, holistically, probably is a net positive. In my experience with students specifically—and this is something I hear from every teacher, educational assistant, counselor, parent, coach, and administrator I've spoken with—cell phones and social media have had a massive negative impact on quality of life for teens. A few examples:

- Sleep: huge numbers of kids have terrible sleep because they are a) up all night on their devices and b) when they do fall asleep, are constantly awakened by notifications.

- Social pressure and bullying: where these used to semi-end once a student arrived home, social pressures and bullying now happen 24/7. Twenty years ago a student was a target when at school, now they can be thrashed on Twitter—and watch it happen live—all afternoon and night.

- Distraction: in the classroom, phones and social media are a constant battle for teachers, but also simply for students to have extended time focusing on reading/writing/etc.

- Loss of non-screen time activities: I have spoken to student after student and asked what their screen time data show. It was often 10, 11, 12 hours per day. They are sending hundreds of text messages a day. Hours on YouTube/Snap/Twitter/etc. This has to come at the expense of something—outdoors, music, sports, games, sex, etc.—right? That doesn't mean it's a net negative, yet my sense is it is.

- Comparing: there is always something happening and it is being posted about, so kids are constantly comparing their experience with their peers and feeling left out or missed out.

These are just a few things that come to mind. And while it by no means applies to all students, these were exceptionally common themes. Moreover, schools in which I work and as reported by colleagues are overwhelmed with teen mental health challenges—suicidal ideation, depression, anxiety, etc.—at unbelievably high levels. We simply can't keep up.

Now, with all that said, I'm not citing any data or large/small studies that verify these claims. And, of course, I'm not claiming it is a causal relationship that cell phones and social media caused these things. That said, I have hours and hours and hours of experience putting the target squarely on those things.

I'm writing because I thought it would be interesting to hear you expand on your thoughts about social media being a force for good. It would be interesting to see how you make sense of some of the ideas I share above and whether they land or simply sound like a bunch of anecdotal rubbish.

Kevin here again. Since I always have the last word on my own blog, I feel it would be a little unfair to say a lot about this. But I'll toss out a few comments.

I'm not a teacher, but I've heard all this stuff too. I don't question that it's real. But what I really want to know is how widespread it is. Here are a few more detailed comments that help to address this.

Sleep: At the risk of being Pollyannish, surely parents can simply take cell phones away from their kids at night if it's truly causing havoc with their sleep? Or would I just get laughed at for suggesting something so naive? This Pew survey from 2019 is also worth a look:

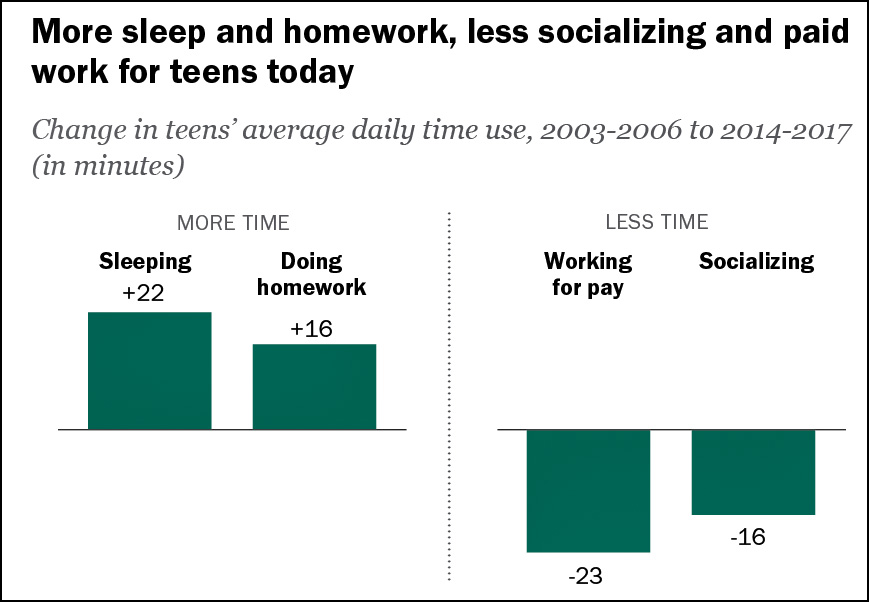

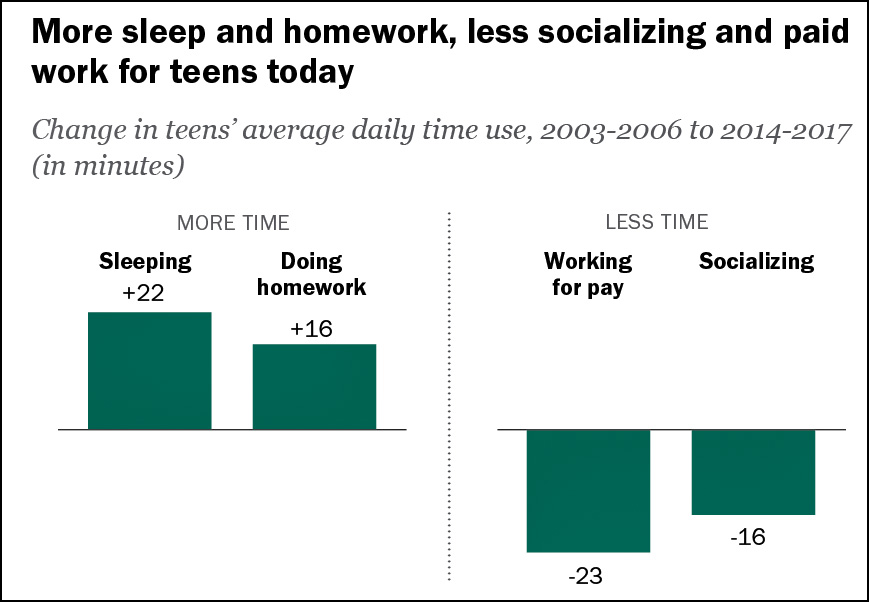

This is typical of research vs. anecdote, and it's hard to know which to accept. But if Pew is to be believed, kids are getting more sleep than they used to—though I can't figure out what could possibly have caused this.

This is typical of research vs. anecdote, and it's hard to know which to accept. But if Pew is to be believed, kids are getting more sleep than they used to—though I can't figure out what could possibly have caused this.

24/7 bullying: Point taken. That said, survey evidence suggests—surprisingly—that cyberbullying has been pretty flat over the years. In addition, the total amount of bullying has actually decreased.

Distraction: I've heard about this problem since long before social media was popular. It sure seems like there ought to be some kind of decent answer that doesn't involve all the kids tossing their phones in a sack or something.

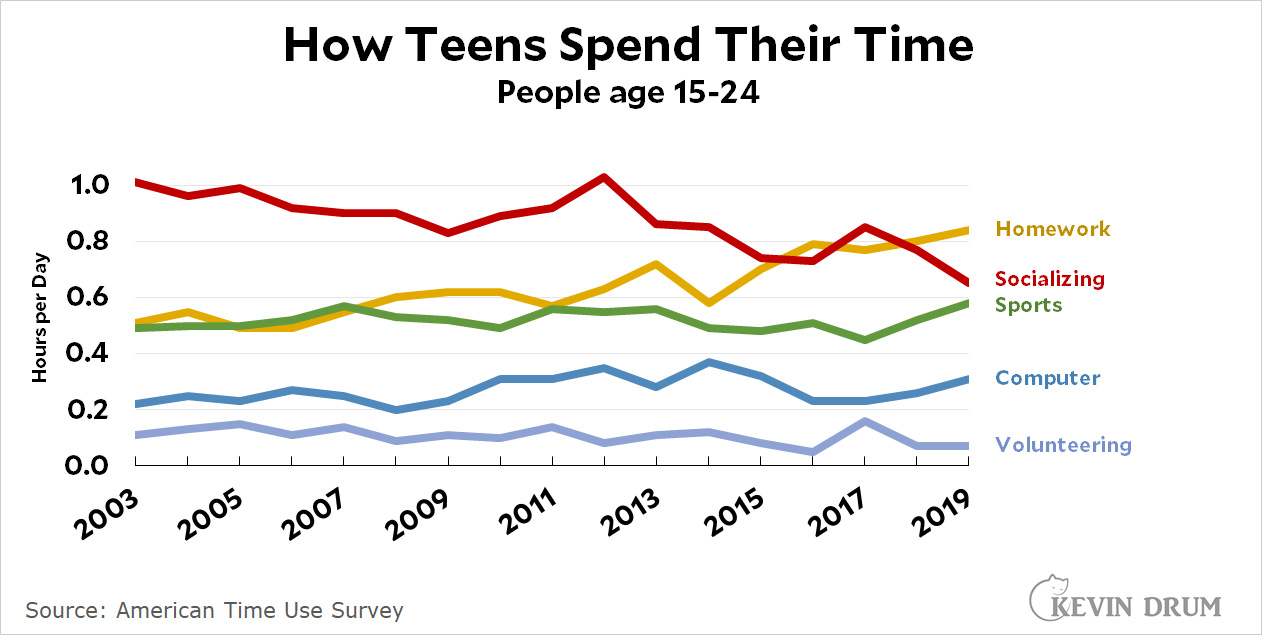

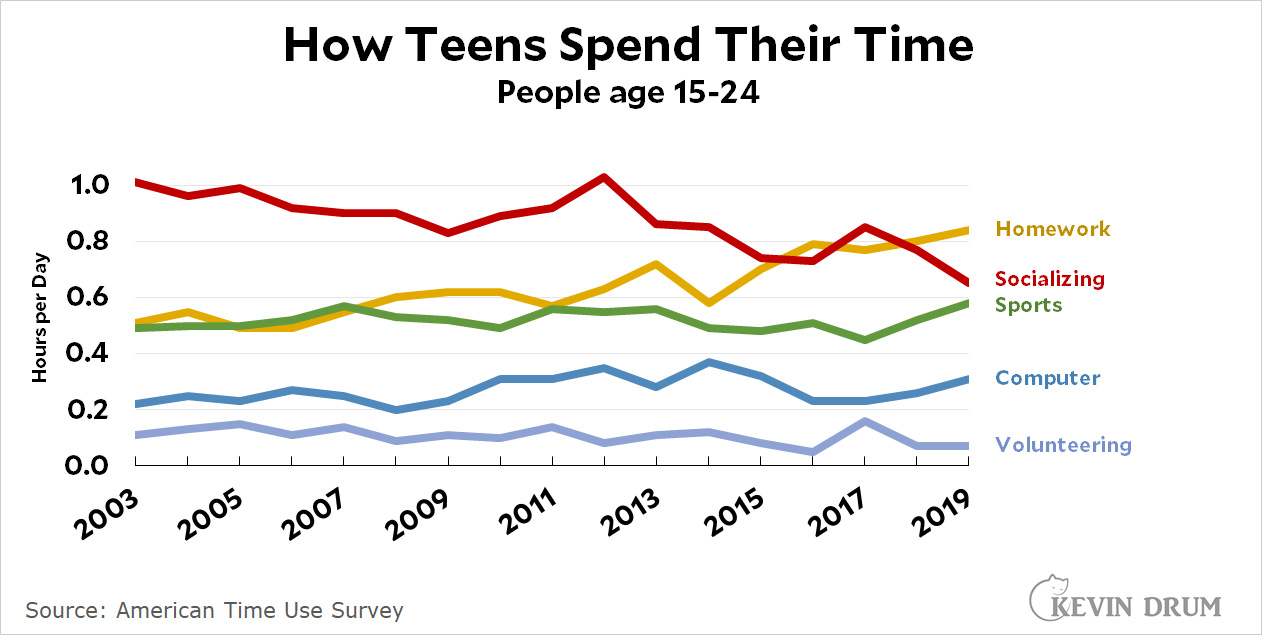

Non-screen activities: This is an interesting one! So I headed over to the American Time Use Survey conducted every year by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Here's what it tells us:

The ATUS is a high-quality survey of long standing. However, it only breaks down the youngest age group to 15-24, which is obviously a problem. Also, it's oriented toward adults and doesn't include any questions about cell phone or social media use.

The ATUS is a high-quality survey of long standing. However, it only breaks down the youngest age group to 15-24, which is obviously a problem. Also, it's oriented toward adults and doesn't include any questions about cell phone or social media use.

That said, sleeping is up a bit and TV watching is down a bit. The chart above shows everything else of interest. In-person socializing is down, but homework and sports are up, and volunteering is pretty steady. If ATUS can be trusted, teens and young adults aren't cutting back on non-screen activities.

FOMO: I don't have anything to say about this aside from the fact that it's been a central fact of teen life pretty much forever.

Put this all together, and it's hard to pick out a serious impact from social media. So I'll toss out some speculation: there are some kids who are heavy social media users, but their numbers are small enough that they don't move the needle on survey averages. However, their problems are big enough that they do overwhelm teachers in person. As we all know, a few unruly kids can disrupt an entire class.

That's just a guess, though. Another possibility is that survey instrument averages are just too crude to pick up much, and anecdotal evidence really is superior.

And finally, I've heard so much about the deterioration of teen mental health that I definitely believe this is a real thing. What I don't know is what's causing it. Social media is an obvious candidate, but there are others too.

I guess I ended up writing a lot about this after all. Sorry. Welcome to the life of a blogger.

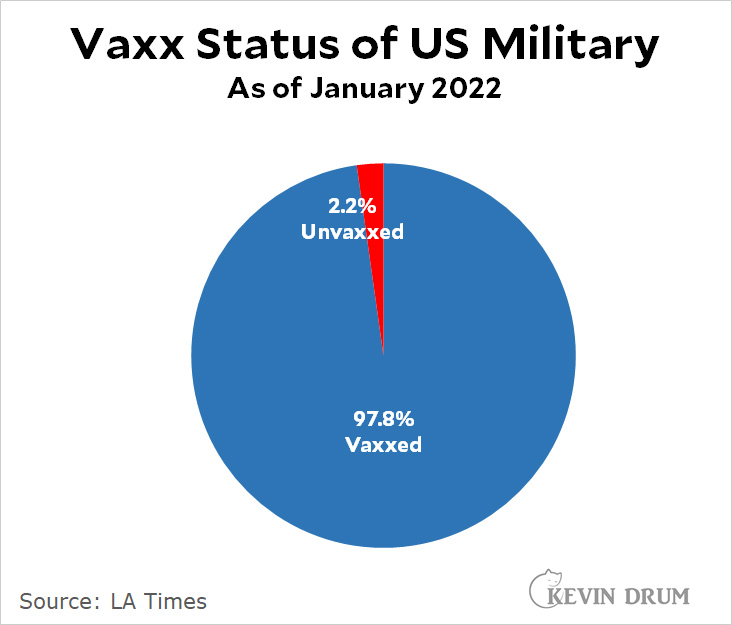

Sigh. If we could do this well for the whole country the pandemic would be over.

Sigh. If we could do this well for the whole country the pandemic would be over.