A recent investigation of ticketing in Chicago produced a dismal result:

A ProPublica analysis of millions of citations found that households in majority Black and Hispanic ZIP codes received tickets at around twice the rate of those in white areas between 2015 and 2019.

....The coronavirus pandemic widened the ticketing disparities....In 2020, ProPublica found, the ticketing rate for households in majority-Black ZIP codes jumped to more than three times that of households in majority-white areas.

Racist cops? Unconscious bias? No. These are tickets issued automatically by red-light cameras and speed cameras:

From California to Virginia, citizens groups, safety organizations, elected officials and others are pointing to cameras as a “race-neutral” alternative to potentially biased — and, for many Black men, fatal — police traffic stops. And more funding for cameras may be coming: The federal infrastructure bill passed last fall allows states to spend federal dollars on traffic cameras in work and school zones.

The obvious conclusion from this is that Black drivers speed more than white drivers and run red lights more than white drivers. But this possibility is literally not even mentioned in the entire 4,000-word article.

So what's the explanation? The authors believe it's because streets in majority Black neighborhoods tend to be wide and straight, like this:

Conversely, streets in white neighborhoods tend to be narrow and curvy, which automatically induces drivers to slow down.

Conversely, streets in white neighborhoods tend to be narrow and curvy, which automatically induces drivers to slow down.

Maybe so—though the authors present only the thinnest evidence for this. And of course it does nothing to explain why Black drivers run red lights at much higher rates than white drivers.

The authors also suggest the Black-white disparity has something to do with proximity to freeways, density of neighborhoods, and violent crime rates. But all of this stuff is correlated, so it's just another way of saying "low-income Black neighborhoods."

It sure is a lot of words, and a lot of tap dancing, just to avoid acknowledging the possibility that Black drivers speed more than white drivers. Especially since the authors acknowledge that speed cameras really do work to enhance safety, thus keeping actual existing Black neighborhoods safer.

But I will say this: why doesn't the city put up signs warning drivers that a speed camera is ahead? After all, they say the purpose of the cameras isn't to raise money, it's to get people to slow down. Wouldn't a warning sign be pretty effective at getting people to slow down?

On a separate note, the article also discusses the burden of "fees and fines" on the Black community. It's one thing to get a ticket if you're a middle class white person—you just grumble and pay it—but quite another if your income is low and you don't always have $100 or $200 lying around. So you put it off, and then the late fees pile up, and then you're even further in debt, etc.

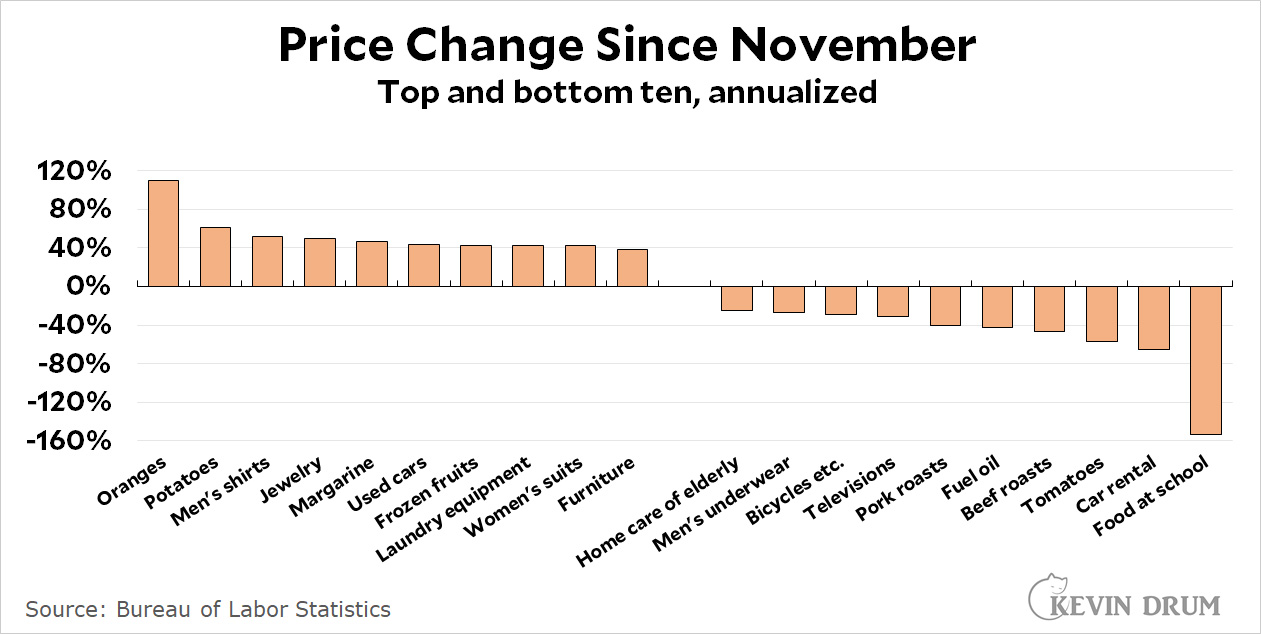

My favorite technocratic approach to this is to scale fines to income. For example, a particular speeding ticket might cost you 0.2% of your income:

I wonder how hard something like this would be to implement? I wonder how many affluent folks would scream about it?

I wonder how hard something like this would be to implement? I wonder how many affluent folks would scream about it?