A piping new Harvard/Harris poll is out, and it has lots of fascinating stuff on a whole bunch of different levels. Let's dig in.

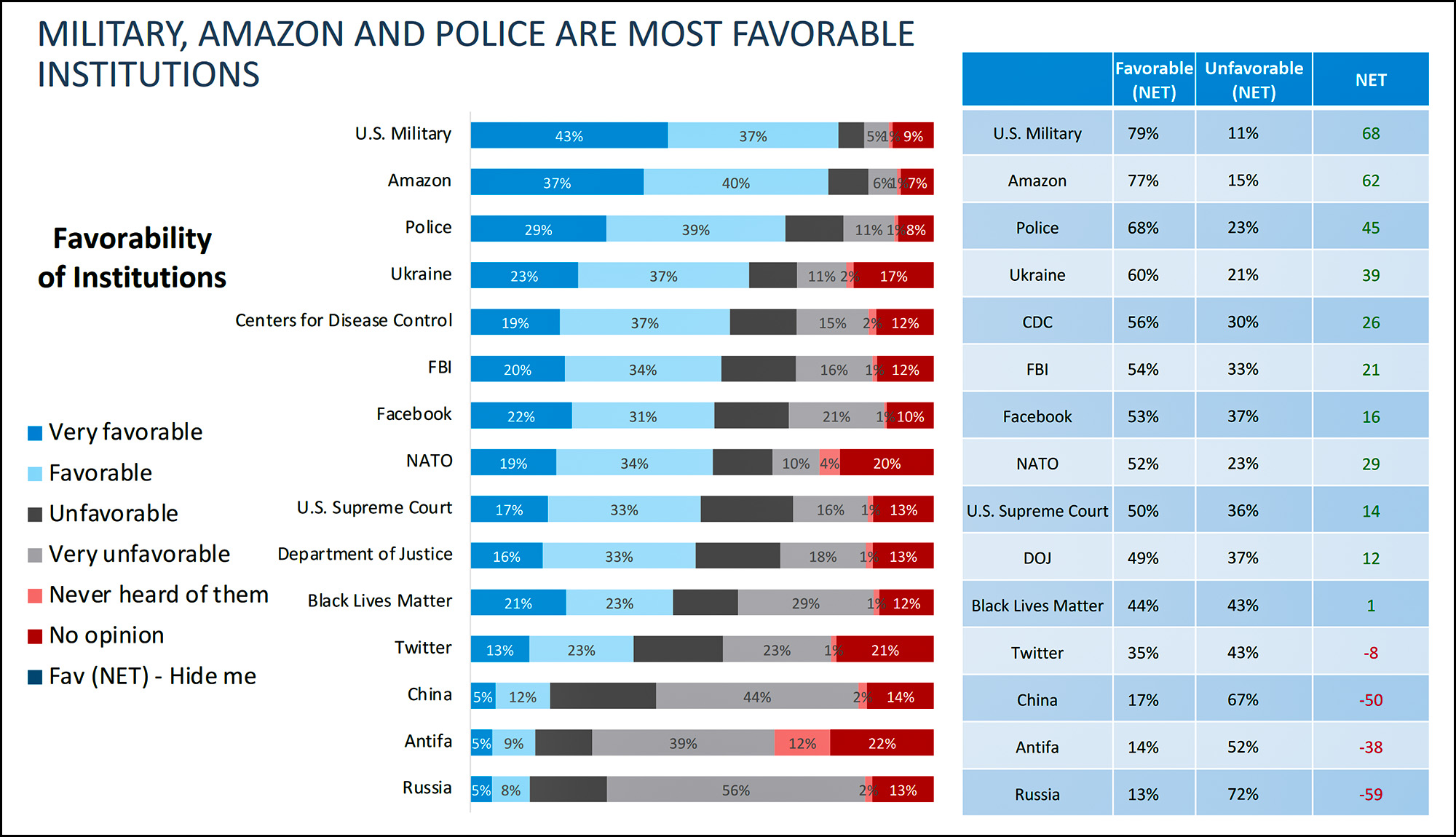

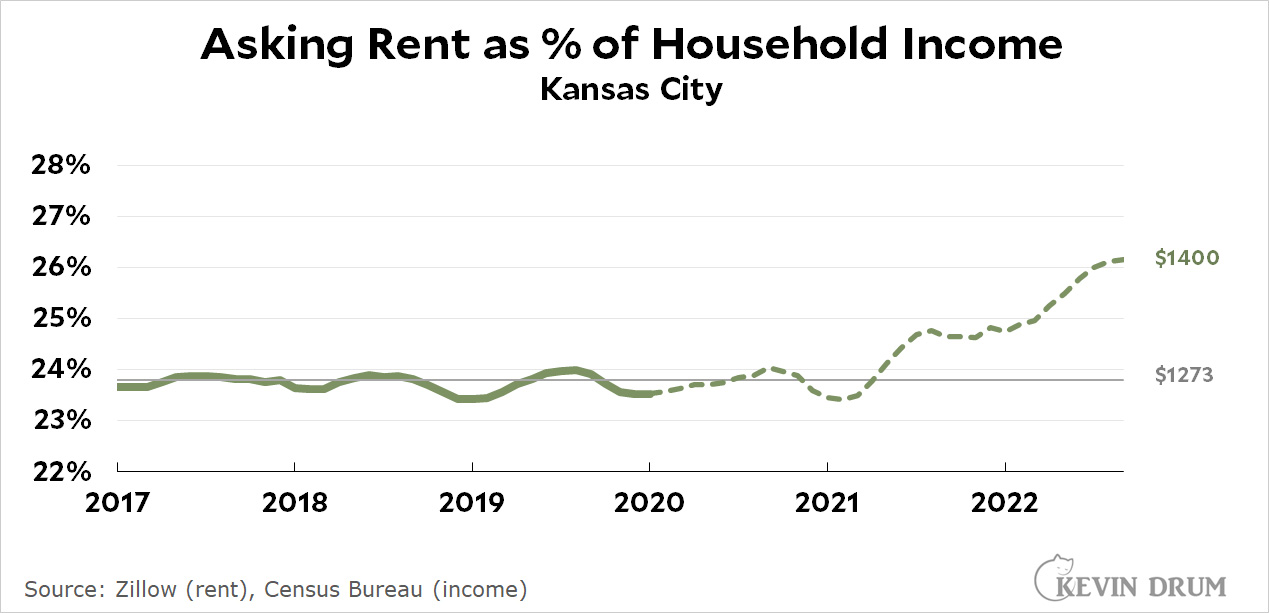

For starters, it turns out that of all the institutions they surveyed, Americans trust Amazon more than almost anything:

Hell, I don't even blame people for this. Amazon's service isn't as good as it used to be, but it's still pretty damn good. Also worth noting: the CDC remains pretty popular despite everything.

Hell, I don't even blame people for this. Amazon's service isn't as good as it used to be, but it's still pretty damn good. Also worth noting: the CDC remains pretty popular despite everything.

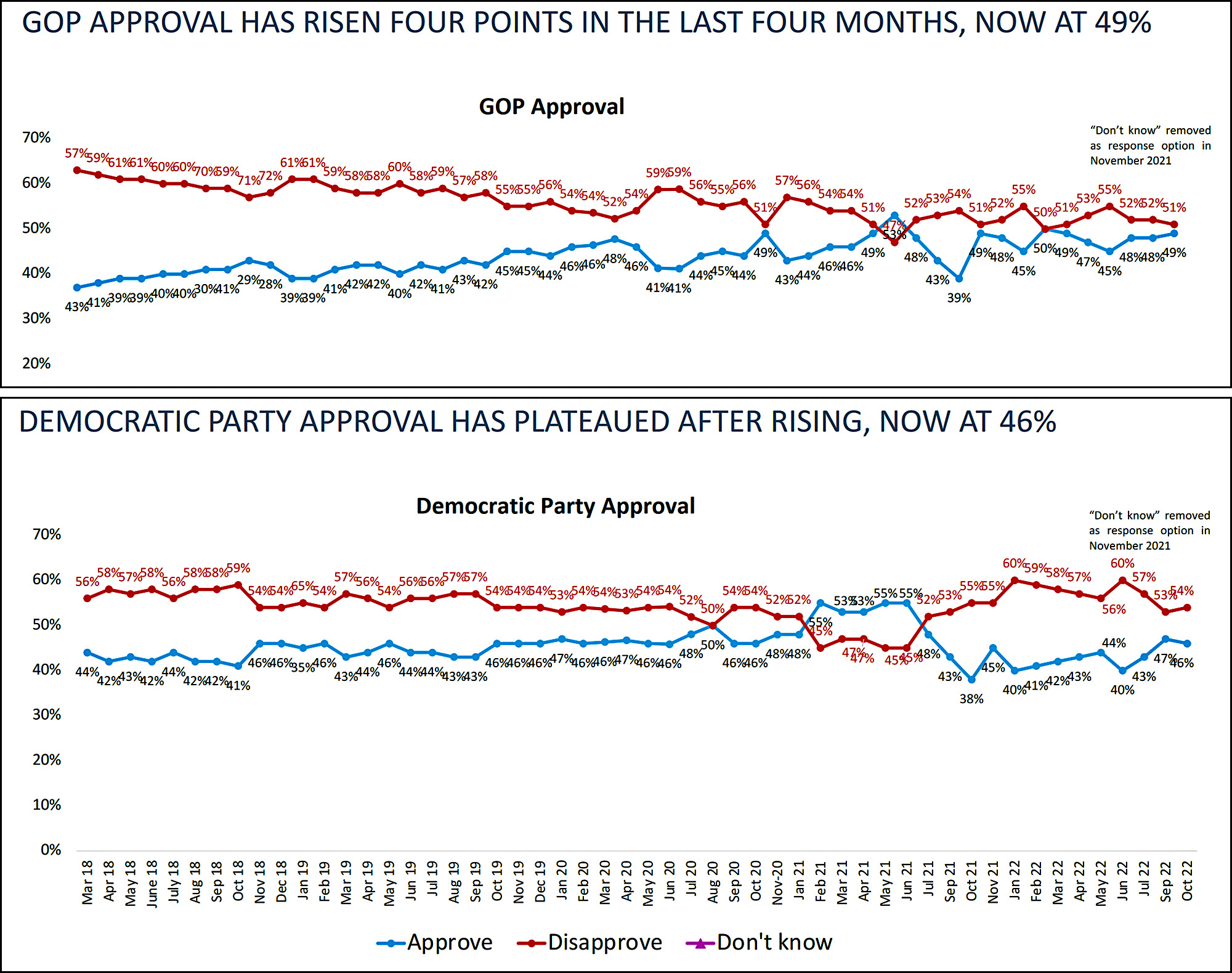

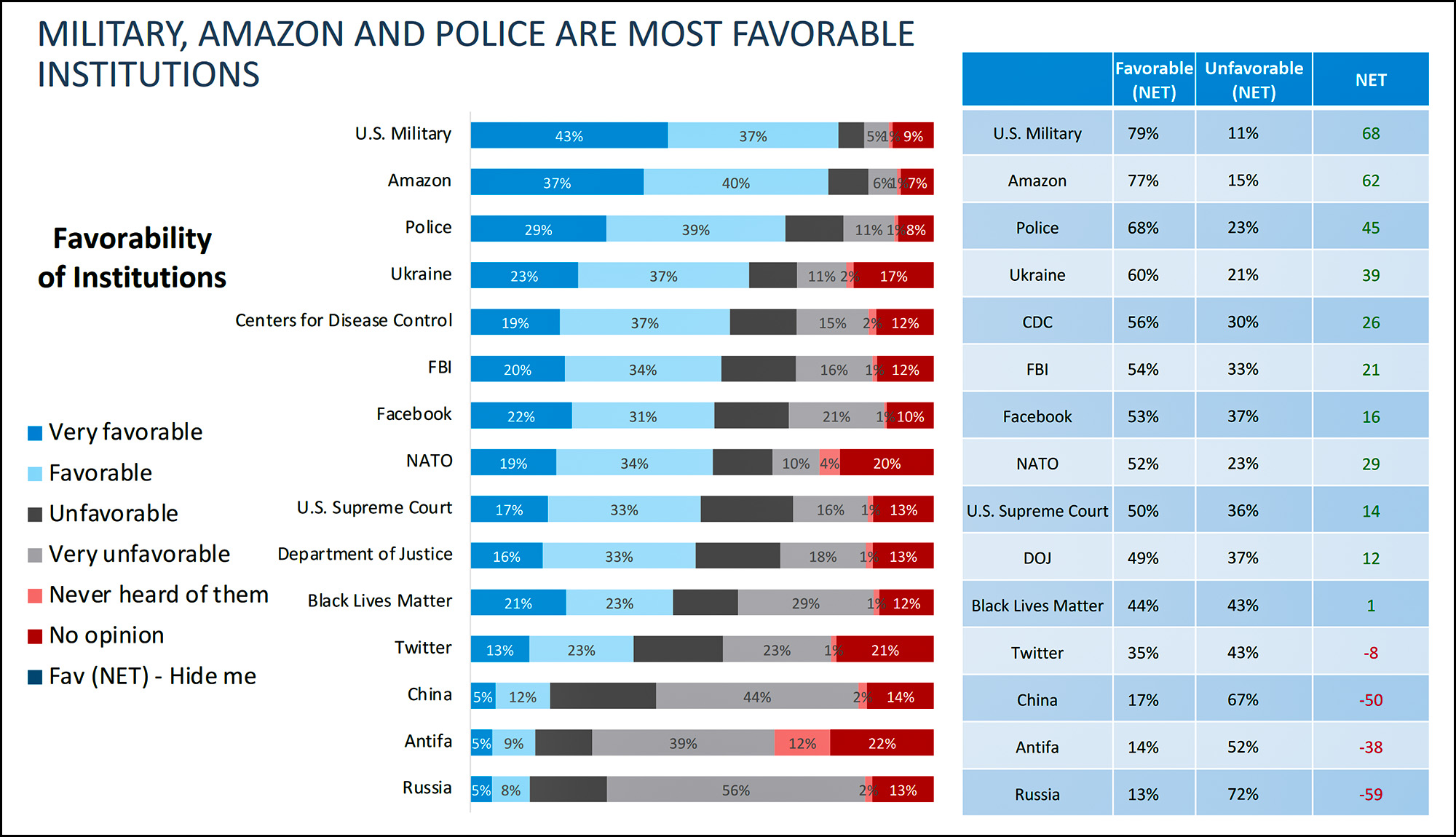

Next up, take a look at the wording of these two headlines:

In the past four months, GOP approval has risen four points. During the same time, Democratic approval has risen six points. So why the pretzel-bending effort to pretend that Republicans are making more progress with voters?

In the past four months, GOP approval has risen four points. During the same time, Democratic approval has risen six points. So why the pretzel-bending effort to pretend that Republicans are making more progress with voters?

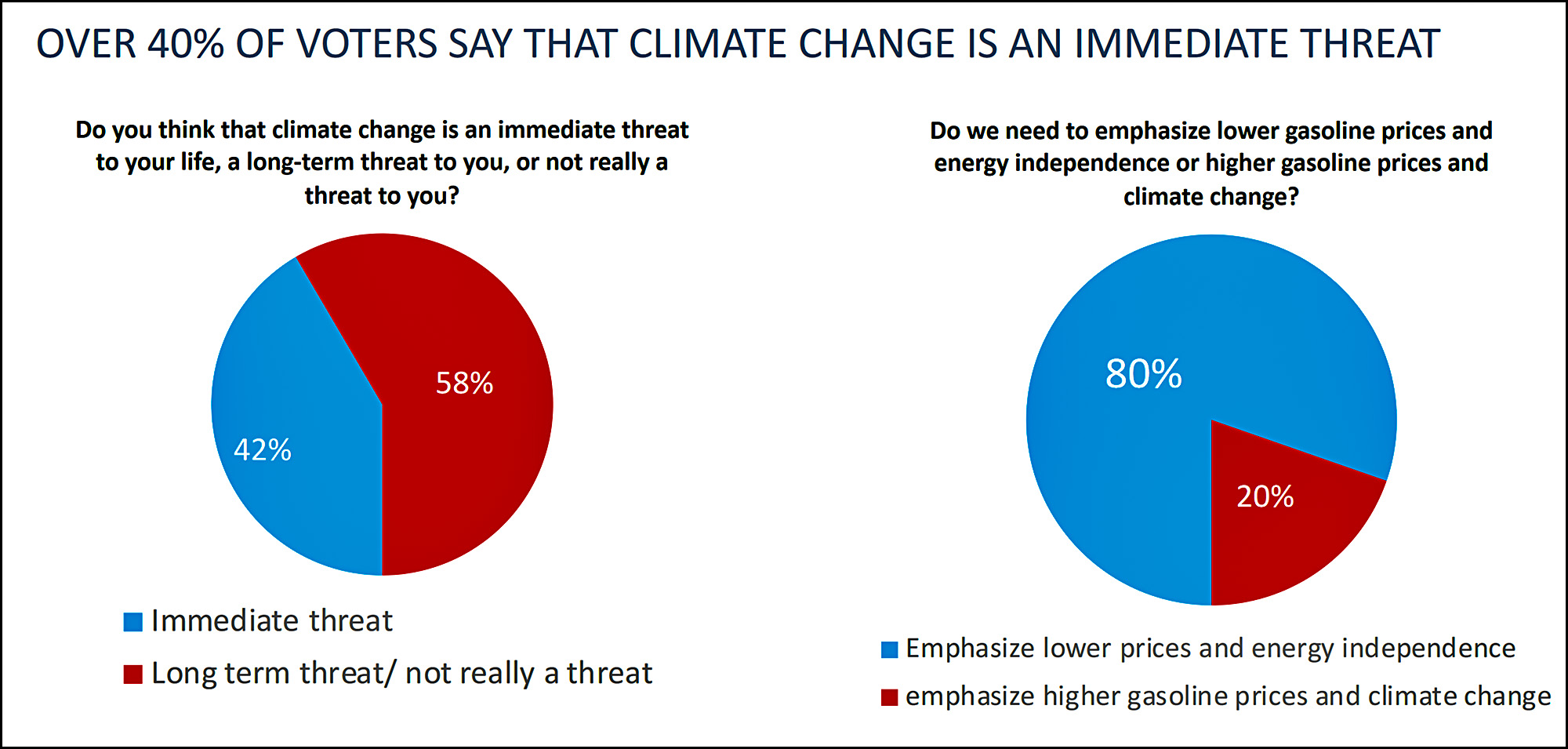

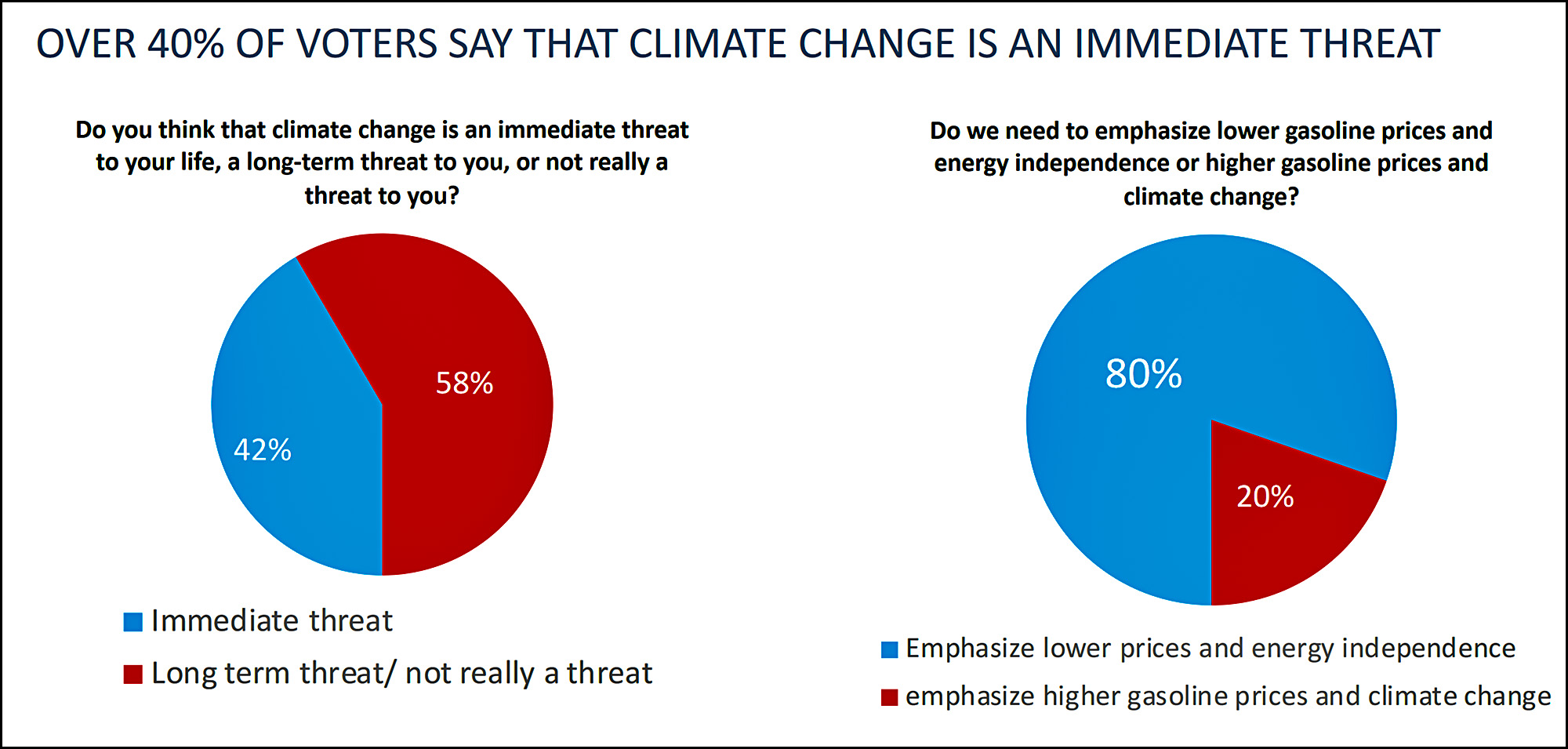

The next one is dedicated to Dave Roberts:

Among those surveyed, 42% think climate change is an immediate threat, but only 20% think it should be prioritized over higher gasoline prices. Sigh.

Among those surveyed, 42% think climate change is an immediate threat, but only 20% think it should be prioritized over higher gasoline prices. Sigh.

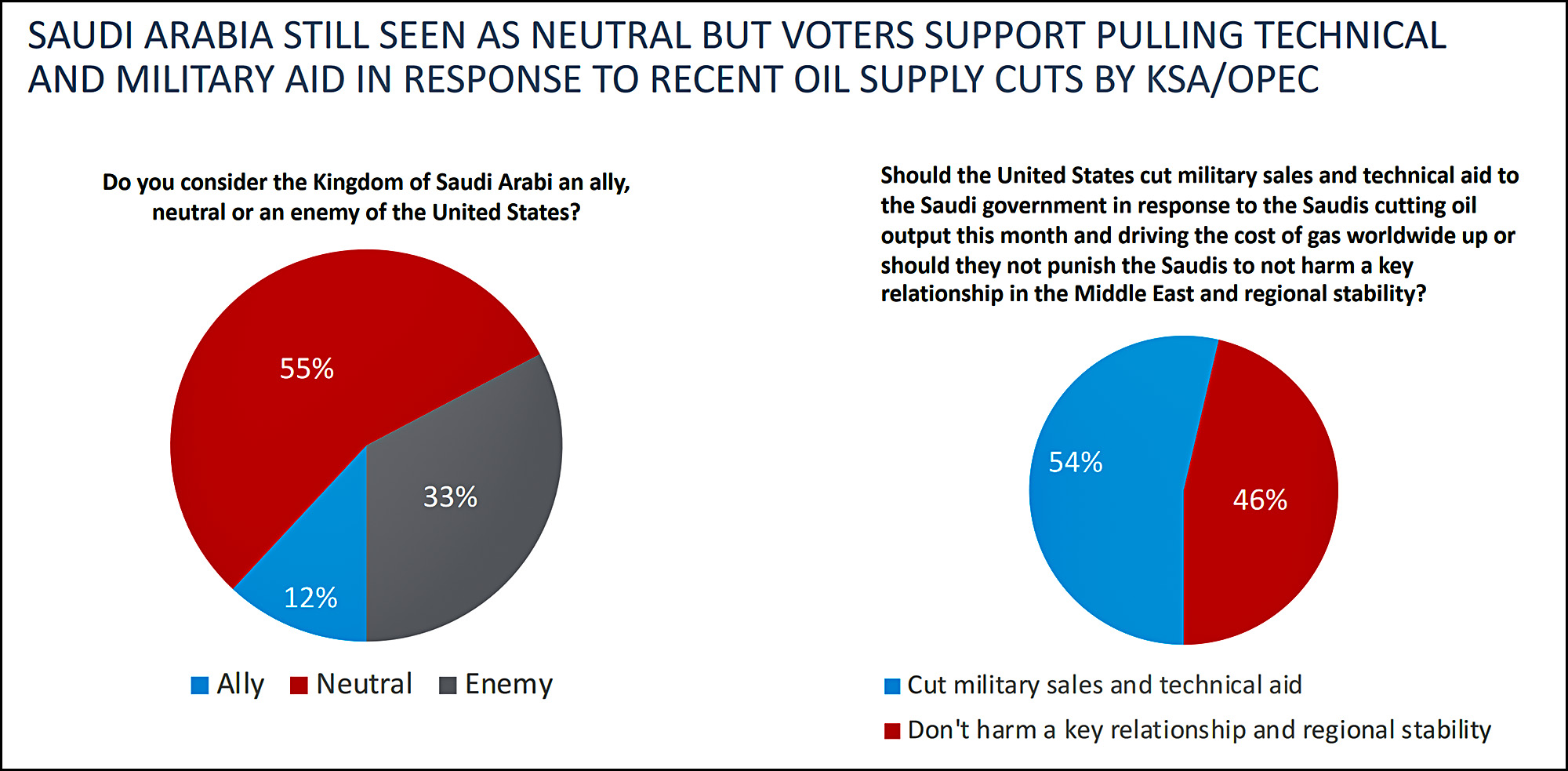

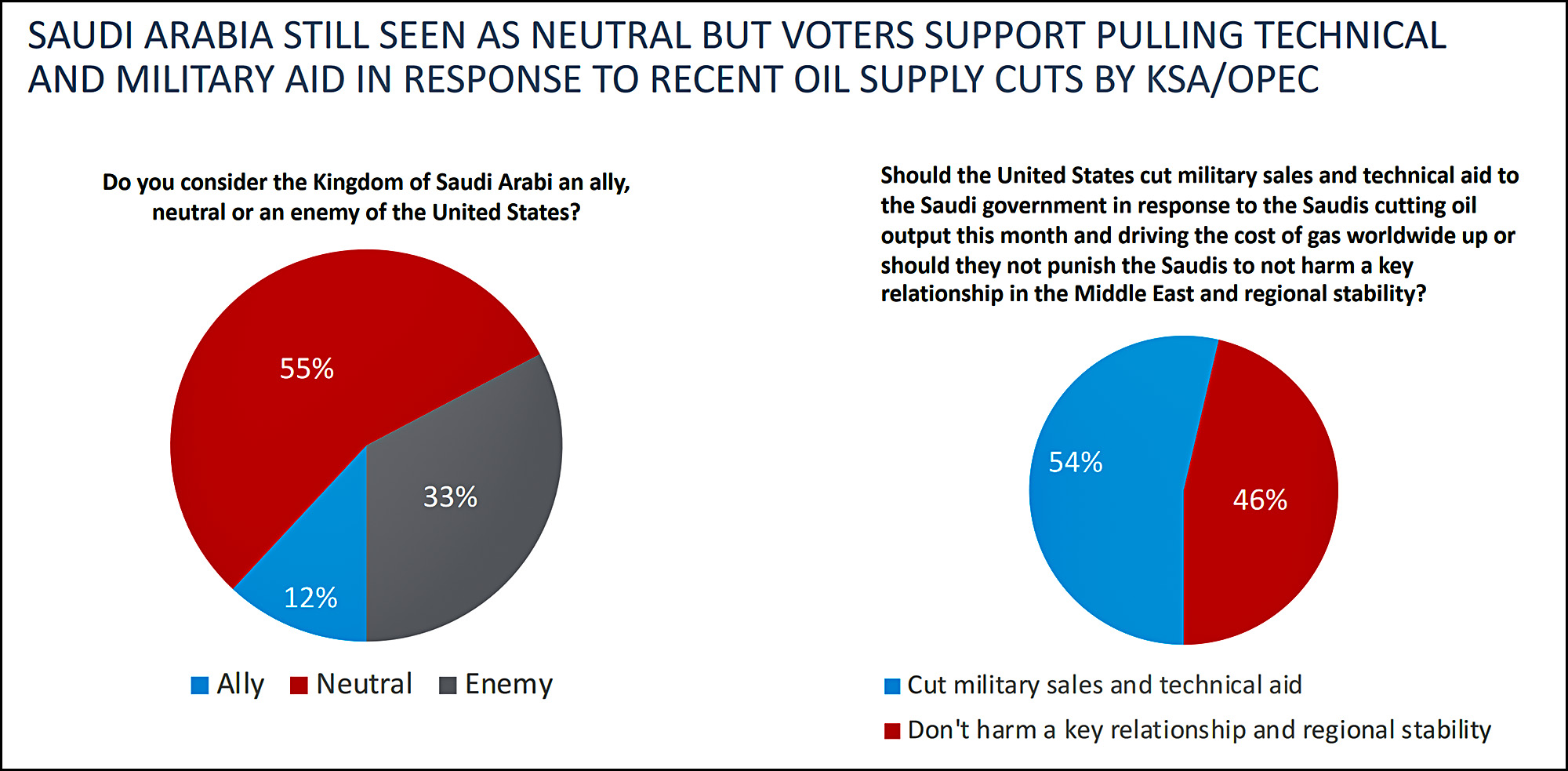

And speaking of oil, only 12% of Americans view Saudi Arabia as an ally while a full third view it as a straight-up enemy:

And yet, nearly half of all people still don't want to harm this "key relationship." Sigh again.

And yet, nearly half of all people still don't want to harm this "key relationship." Sigh again.

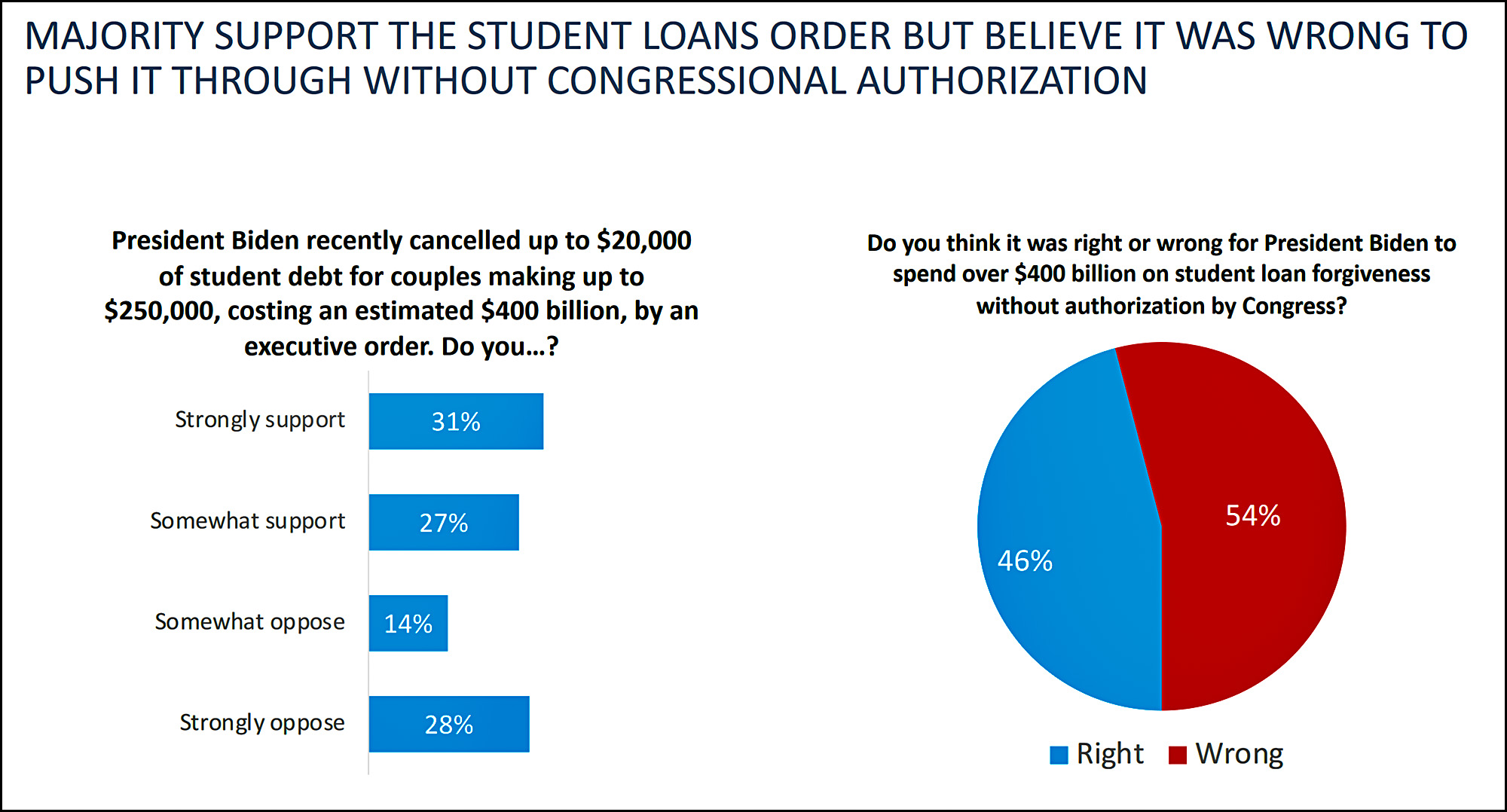

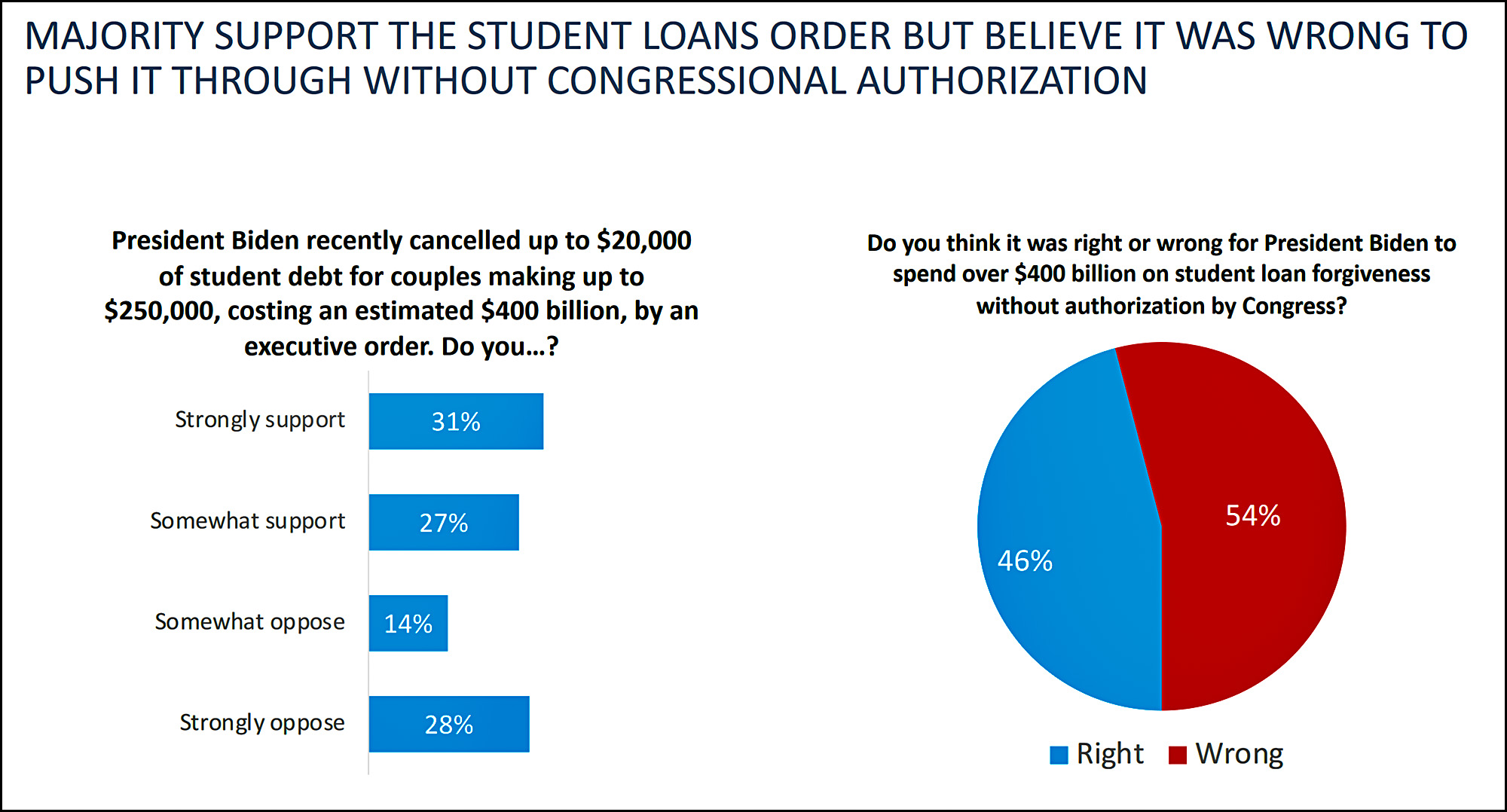

Check this out: 58% of Americans support President Biden's student loan cancellation, but only 46% think it was right for him to do it:

Apparently there are about 12% of Americans who favor this and don't give a damn if it was legally right or wrong. I'm surprised the number is this low—and I'll bet in real life it's actually much higher. I suspect most people never admit things like this even to themselves and accidentally told the truth this time only because they were taken by surprise.

Apparently there are about 12% of Americans who favor this and don't give a damn if it was legally right or wrong. I'm surprised the number is this low—and I'll bet in real life it's actually much higher. I suspect most people never admit things like this even to themselves and accidentally told the truth this time only because they were taken by surprise.

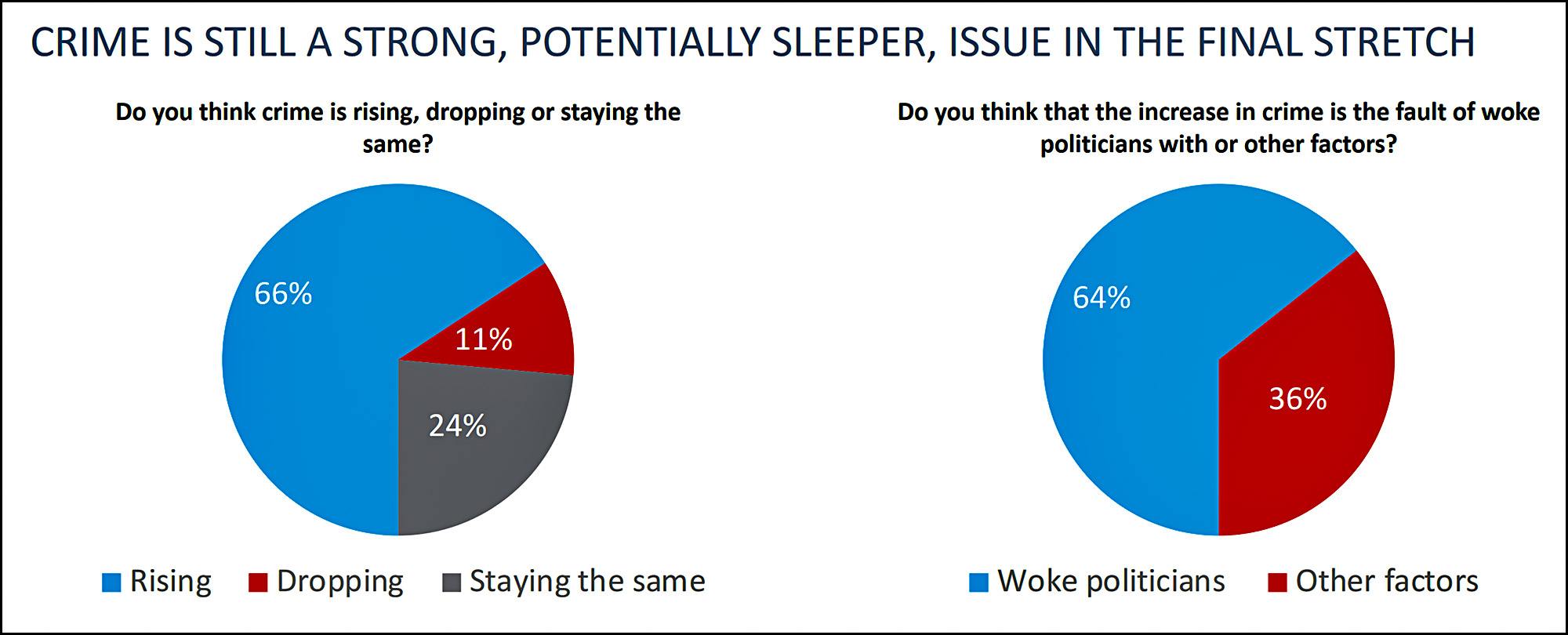

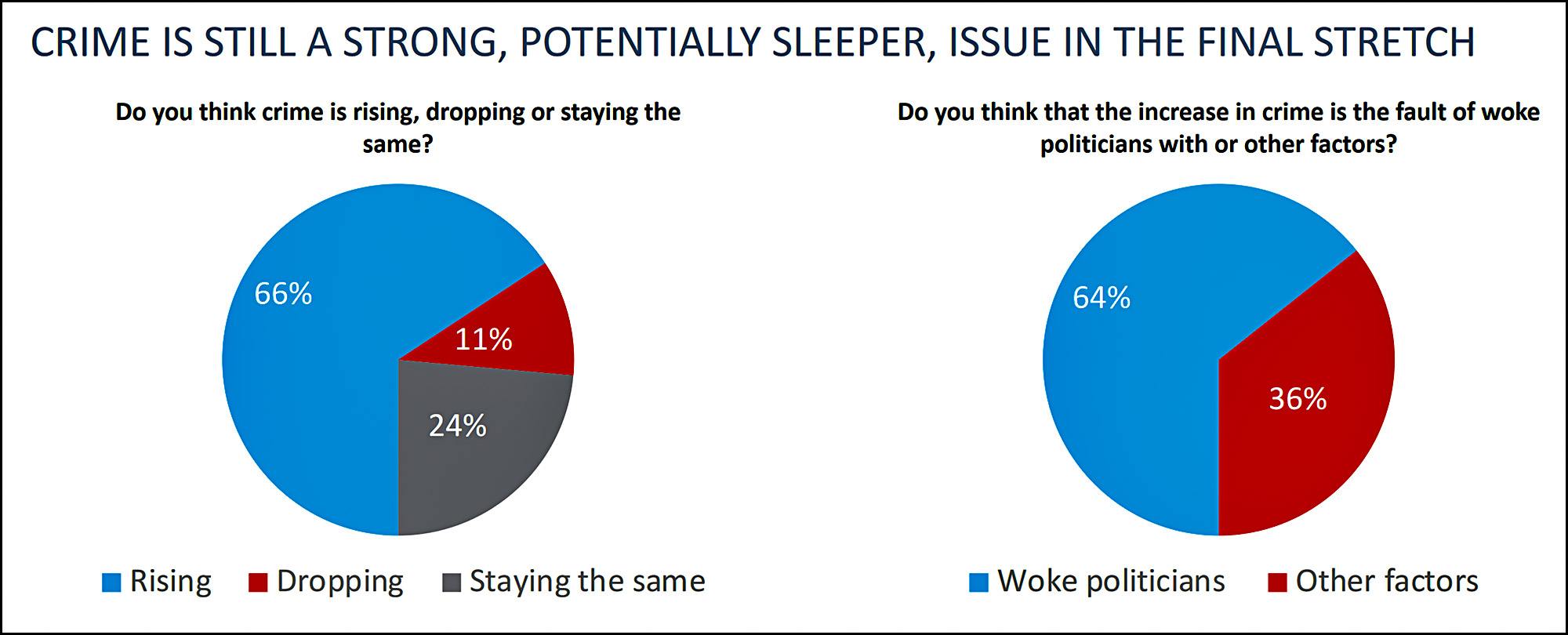

Finally, here is public opinion on crime and wokeness:

I've gotten weary of progressives who insist there's no "proof" that slogans like Defund the Police have done the liberal cause any harm. This just defies common sense.

I've gotten weary of progressives who insist there's no "proof" that slogans like Defund the Police have done the liberal cause any harm. This just defies common sense.

Now, I admit this poll result is not cast-iron proof, but I'd say it's pretty suggestive. And it doesn't make any difference if crime is truly up. Or if woke politicians really are at fault. Or that this result is probably driven by Fox News and Republican advertising. All of those things are part of the real world, and all of them have to be dealt with. Like it or not, this is how things are playing out, and it's done liberals no good.