Nobody wants to read good news, Matt Yglesias says today, and boy howdy is he right. The United States has been practically bursting with good news over the past couple of decades, but no one wants to hear it. We all hate each other so much that we can't stand the thought that lots of things are going right.

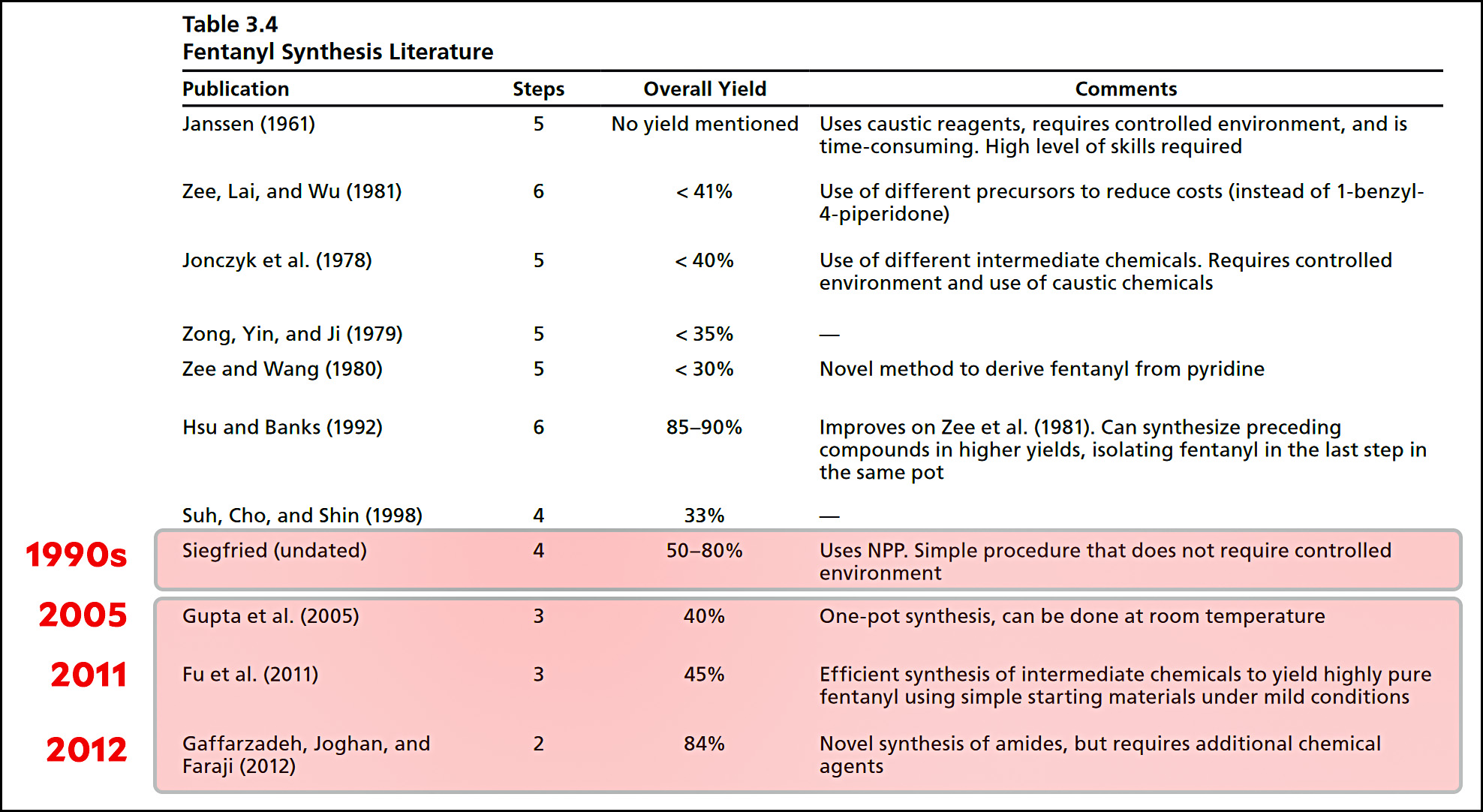

Not everything, of course. Climate change is broiling the planet. We lost lots of good paying manufacturing jobs in the aughts. Opioid overdoses are up.

But even if we restrict ourselves purely to politics, take a look at the past two years:

- Afghanistan withdrawal

- $1.9 trillion COVID stimulus

- Infrastructure bill

- Climate change bill

- Rallying the world to assist Ukraine

- More than 40 federal judges appointed—a near record rate

- CHIPS Act

- PACT Act

- Student loan forgiveness

And in the lame duck session:

- Respect for Marriage Act

- Railroad mediation.

- Electoral Count Reform Act (soon)

- Budget passed. (soon)

Matt adds to this list in a techno-explainer about the clean water act that was passed as part of the NDAA. David Dayen adds a few other good things here.

But overall? David's headline is "Democrats Frittered Away the Lame-Duck Session."

Damn. I'm not picking on David here, and there's nothing wrong with wanting more more more. Still, this was a decent lame duck session even if it didn't produce every last thing Democrats wanted. It's also pretty decent even if it's not the best one ever (Obama's legendary lame duck of 2010). I'd call it a B+ ending to a B+ term, and we should celebrate it while we can, since the next two years are likely to rate a D-.

If you're a straight-A student, a B+ would be a disappointing grade. If you're a B student, a B+ would be pretty good. For a C student it would be great.

I submit that the United States is basically a B student. Not a genius, so to speak, but a good worker who pumps out pretty good results along with a few boners here and there. I don't blame you if you think we should do better, but practically speaking there just aren't many A students among countries—and the very few who might be are a fraction our size. Among large-ish countries, we're arguably #1.

Bottom line: We do pretty well, all things considered, and over the past two years we did even a little better than that. Congratulations, citizens!