Alex Tabarrok and Robert Tucker Omberg have published a new paper which confirms a thought that's been rattling around in my head for a while. The thought is this: aside from vaccines, pretty much nothing has much effect on the spread of COVID-19.

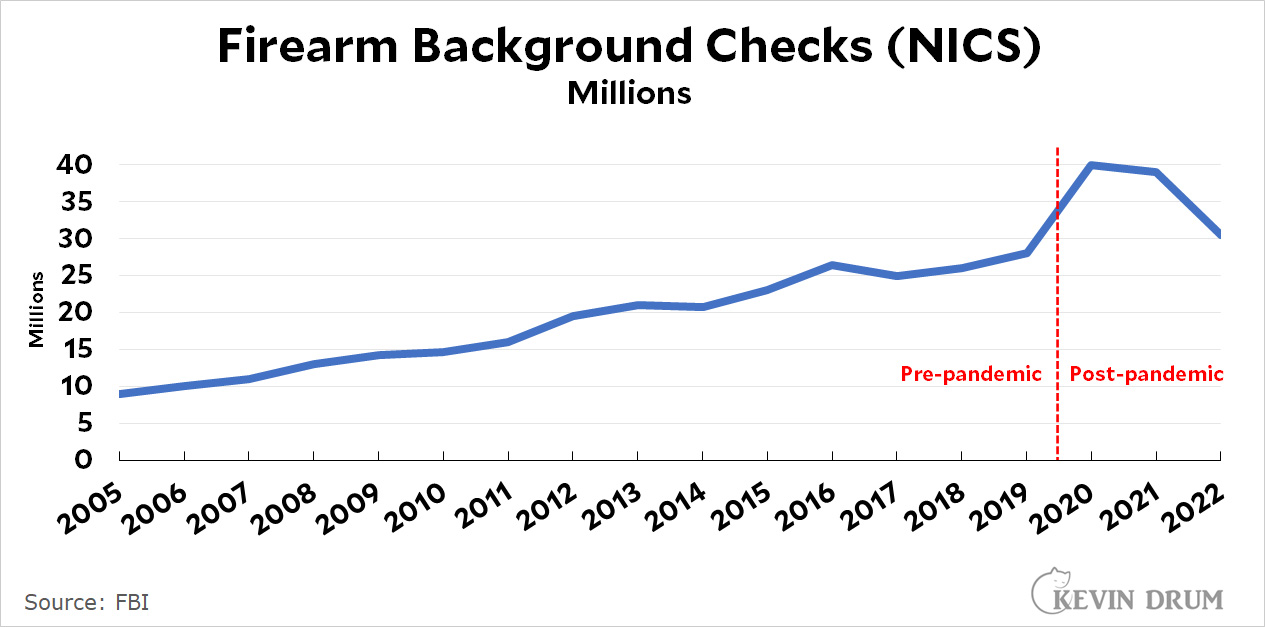

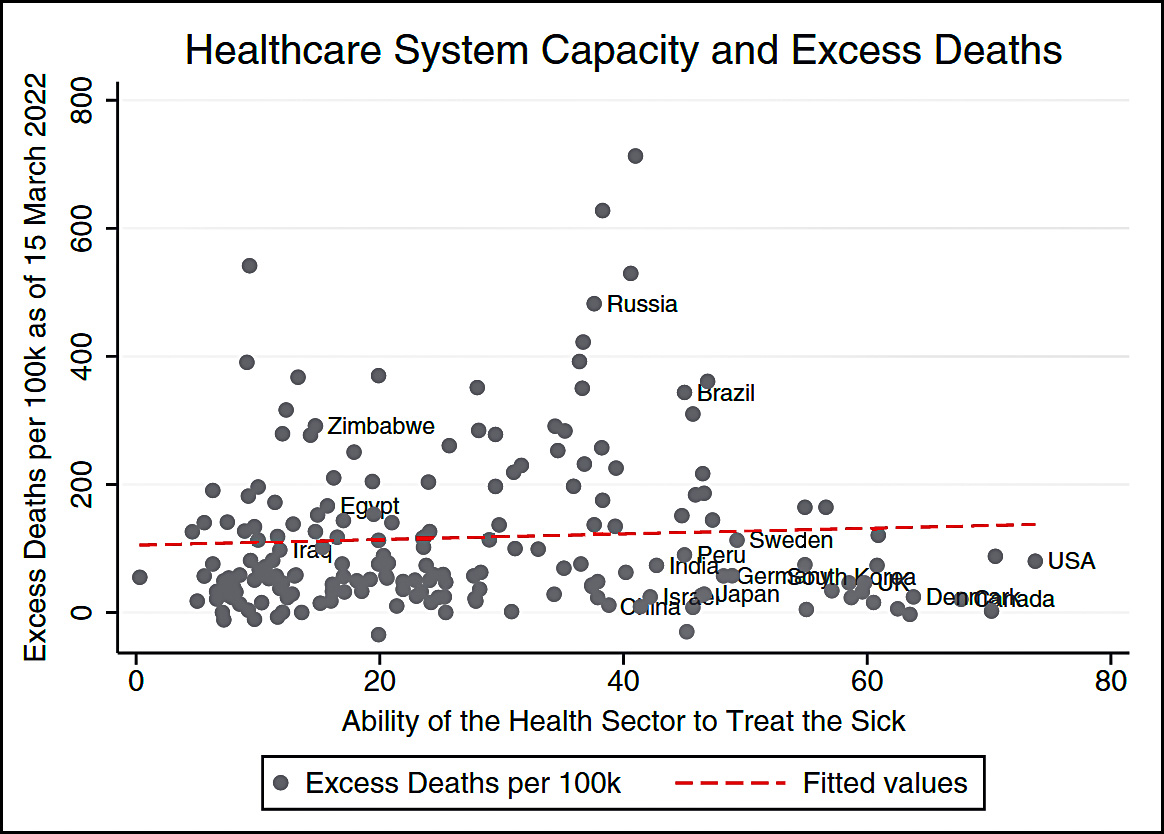

As usual, I'll lead with a couple of charts. The first one measures excess deaths as a function of the quality of a country's health care system:

There should be a downward slope to the regression line, showing that better health care systems lead to fewer deaths. However, there isn't even a modest downward slope. There's a tiny upward slope. Richer, more competent countries had more excess deaths than poorer countries.

There should be a downward slope to the regression line, showing that better health care systems lead to fewer deaths. However, there isn't even a modest downward slope. There's a tiny upward slope. Richer, more competent countries had more excess deaths than poorer countries.

(Note that excess deaths is used here rather than reported COVID-19 deaths. This is because reported deaths are unreliable, especially in poorer countries. Excess deaths are easier to measure and more reliable.)

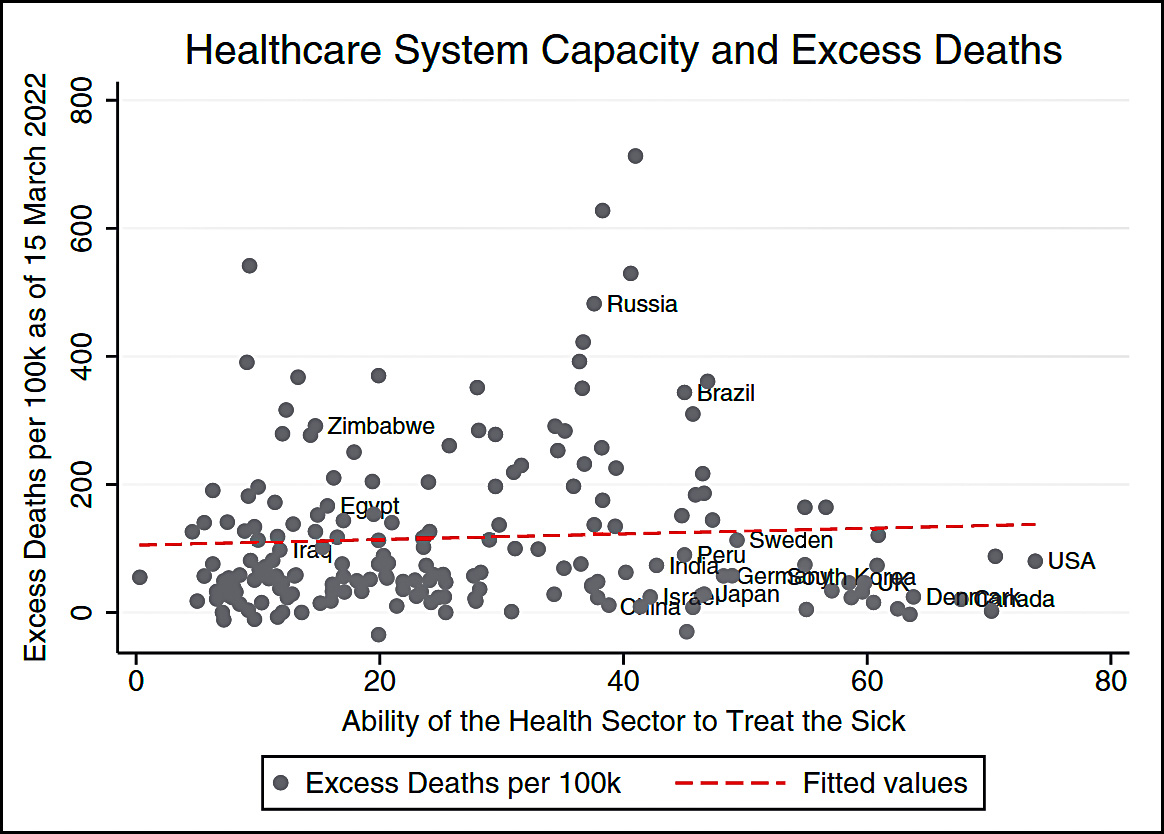

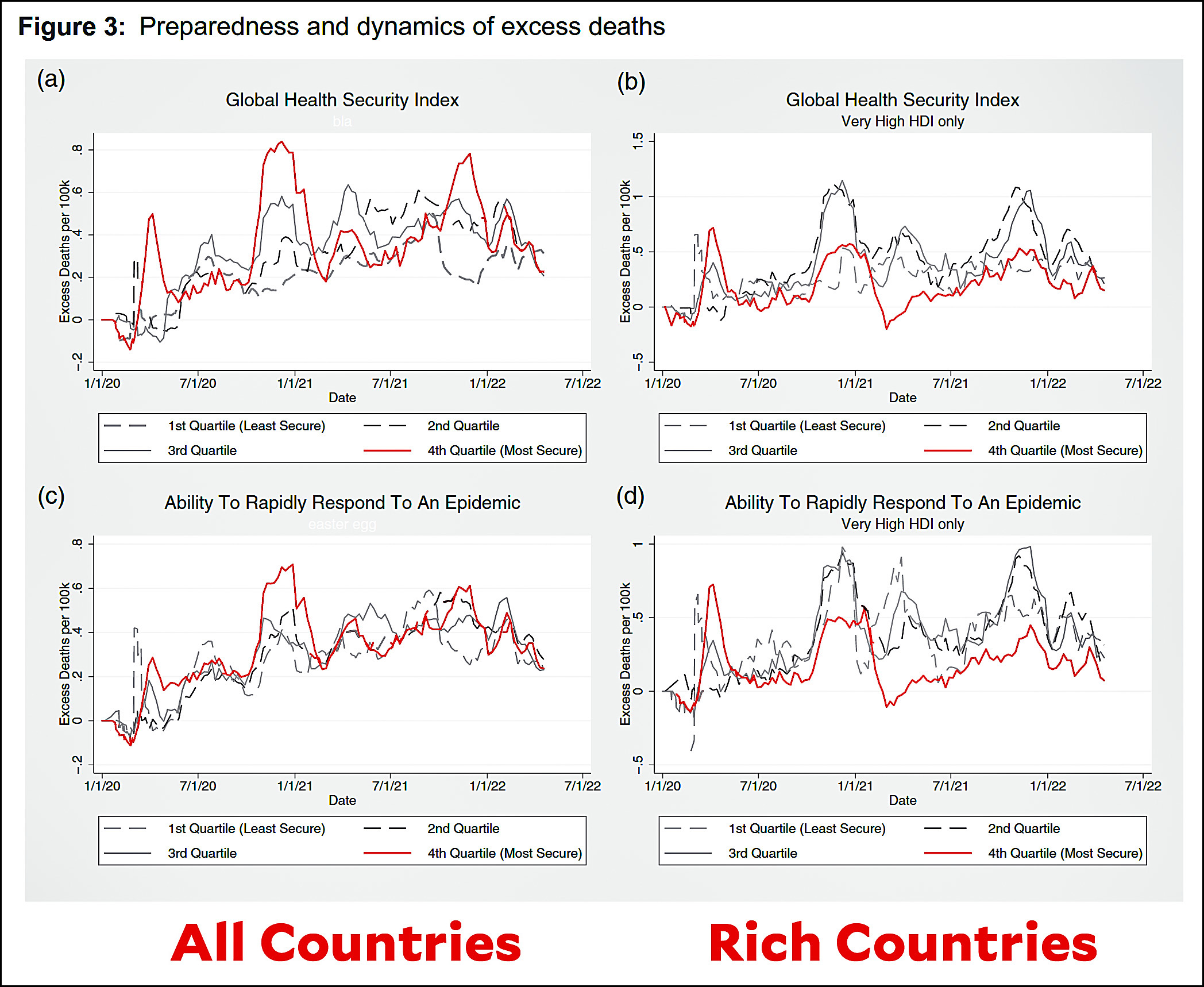

And now here's another chart:

These charts divide countries into four buckets by their level of preparedness for a pandemic, with the red line indicating the most prepared countries. Among all countries, the red line shows nothing special. When you zoom in on just rich countries, those represented by the red line did do better than the others—but not by an awful lot and mostly in the vaccine distribution year of 2021.

These charts divide countries into four buckets by their level of preparedness for a pandemic, with the red line indicating the most prepared countries. Among all countries, the red line shows nothing special. When you zoom in on just rich countries, those represented by the red line did do better than the others—but not by an awful lot and mostly in the vaccine distribution year of 2021.

Nor did anything else studied by the authors make much difference:

Our primary finding is that almost no form of pandemic preparedness helped to ameliorate or shorten the pandemic. Compared to other countries, the United States did not perform poorly because of cultural values such as individualism, collectivism, selfishness, or lack of trust. General state capacity, as opposed to specific pandemic investments, is one of the few factors which appears to improve pandemic performance.

In other words, what's important is not so much preparedness as the willingness to take quick action. That willingness is found mostly in countries that have experienced a recent pandemic and are therefore on alert for a new one.

The authors draw two lessons from all this. First, instead of producing massive planning documents, which mostly fail, we should increase our use of everyday procedures such as routine genomic sequencing and monitoring of sewage discharge. These can give us early warning of a new virus. Second, we should focus our energies on anything that might speed up the development and deployment of vaccines. This is, by a long margin, the most effective way to fight a new pandemic virus.

My take on this is that it by no means tells us to give up and do nothing except develop vaccines. The world didn't respond well to COVID-19, but that doesn't mean we can never respond well to a pandemic. I have a dim view of human nature, but not that dim.

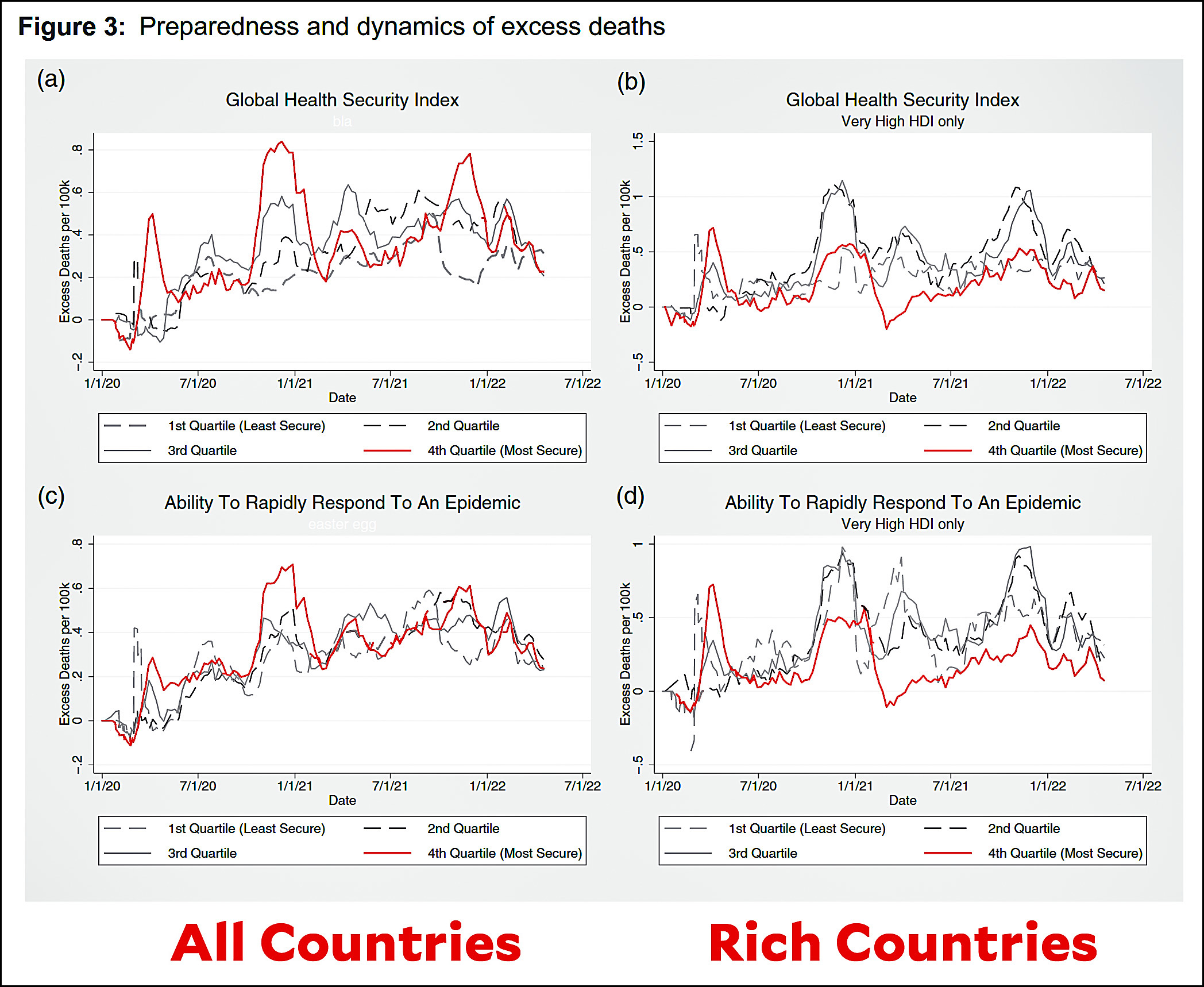

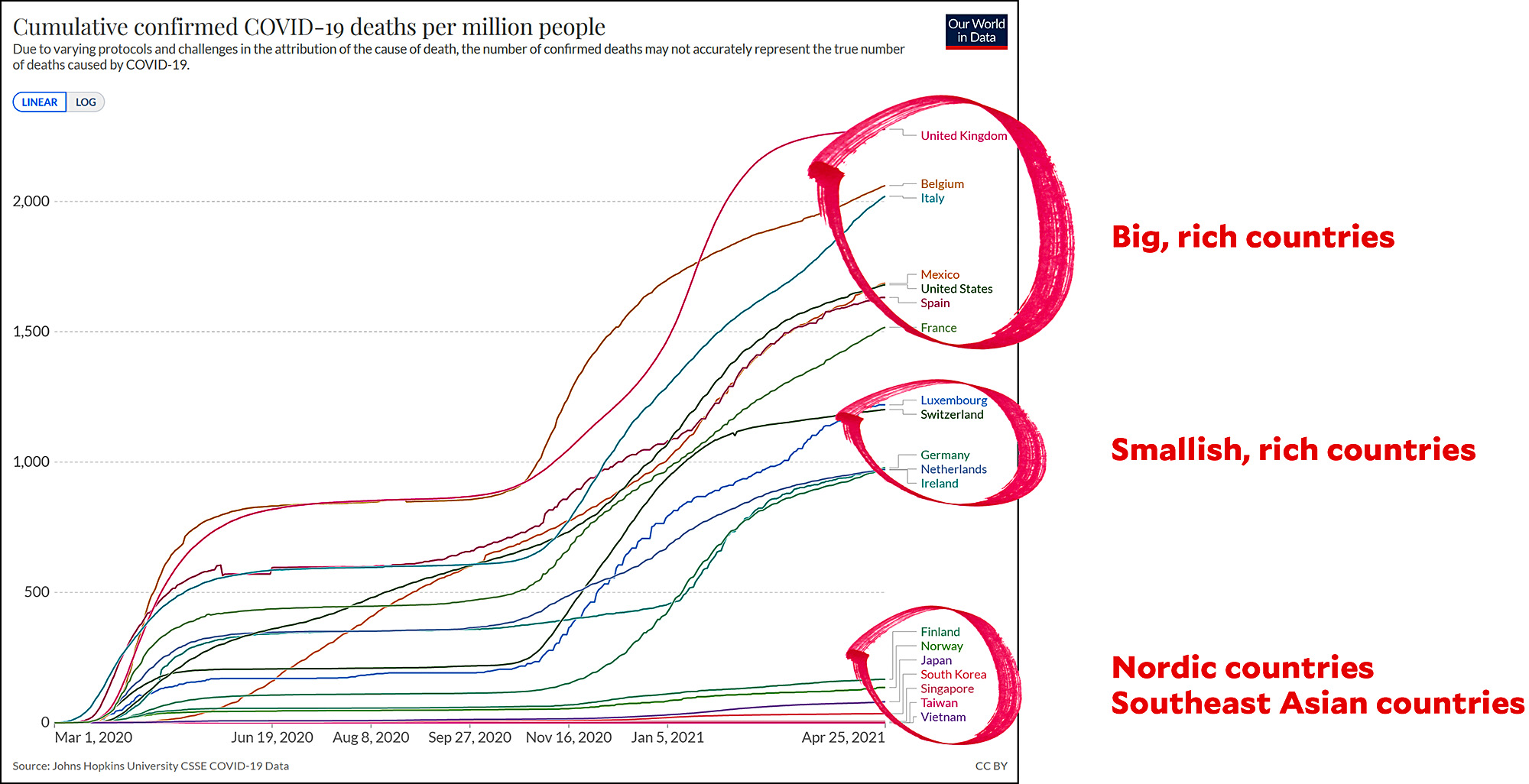

That said, the reason this has all been rolling around in my head is because of a single observation: Although some countries initially did better than others, eventually everyone had to relax. When that happens, you get your turn in the barrel. Here are death rates through the middle of 2021, before vaccines started to overwhelm other factors:

Southeast Asian countries did well because they were still paranoid from the SARS epidemic of a few years ago. Nordic countries did well for some mysterious reason that I don't think we yet understand.

Southeast Asian countries did well because they were still paranoid from the SARS epidemic of a few years ago. Nordic countries did well for some mysterious reason that I don't think we yet understand.

Among other rich countries, there's a (very) rough division between large and small: Large countries generally had higher death rates than small countries. I can think of lots of reasons this could be true, and you should feel free to take a crack at it too. However, as far as I know there's no evidence for anything in particular.

POSTSCRIPT: This is a preliminary study and shouldn't be taken as the final word on anything. Also, like me, the authors might be biased in favor of the results they found. Take this as an opening salvo, but nothing more for now.

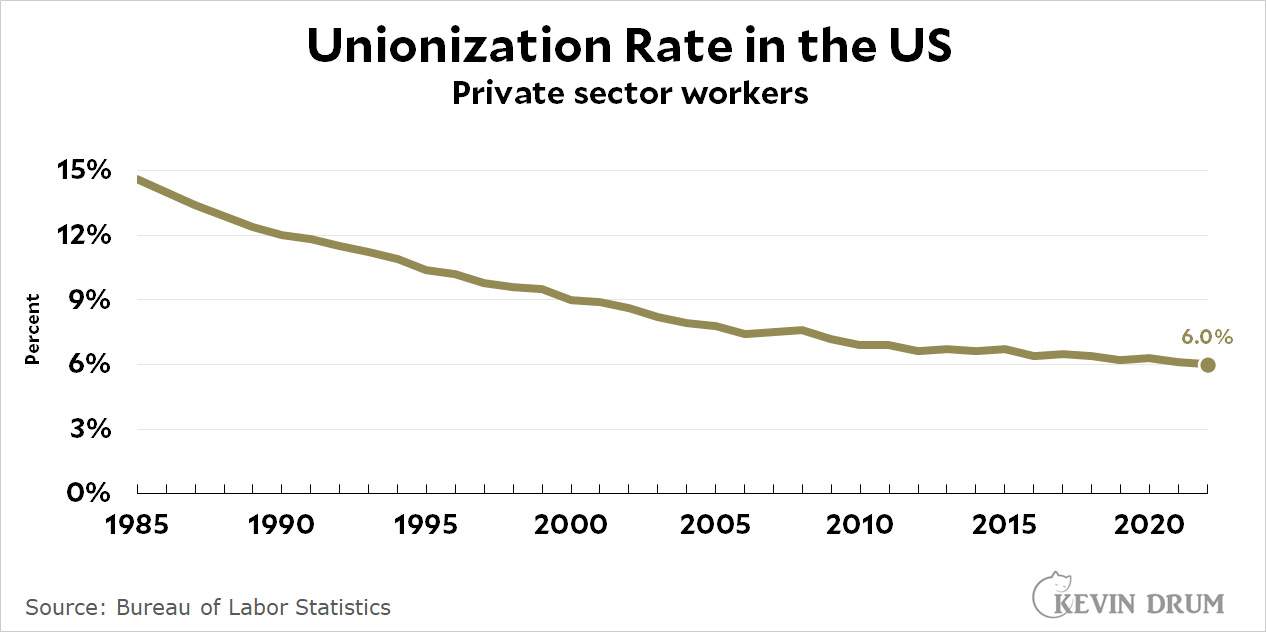

The good news, such as it is, is that the number of private sector union members went up by about 200,000. But that was only because the number of total workers went up. The unionization rate fell from 6.1% in 2021 to 6.0% in 2022.

The good news, such as it is, is that the number of private sector union members went up by about 200,000. But that was only because the number of total workers went up. The unionization rate fell from 6.1% in 2021 to 6.0% in 2022.