The Office of Management and Budget issued a new set of guidelines for regulatory analysis a couple of weeks ago, and it's surprisingly important. It's also pretty technical, so hang on.

The rules are set out in Circular A-4, one of OMB's 136 circulars, and the first thing it addresses is the discount rate that agencies should use. This is a measure of how important the future is. A high discount rate means you're discounting the future and mostly focusing on immediate effects. A low discount rate means you consider future effects important.

To some extent, the value you should use is a matter of opinion. But there is a quantitative method of approximating it: take a look at financial markets and figure out the actual discount rate that's predominant when investors buy things like long-term bonds. The OMB did that, and decided that the discount rate had dropped over the past couple of decades from 3% to 2%.

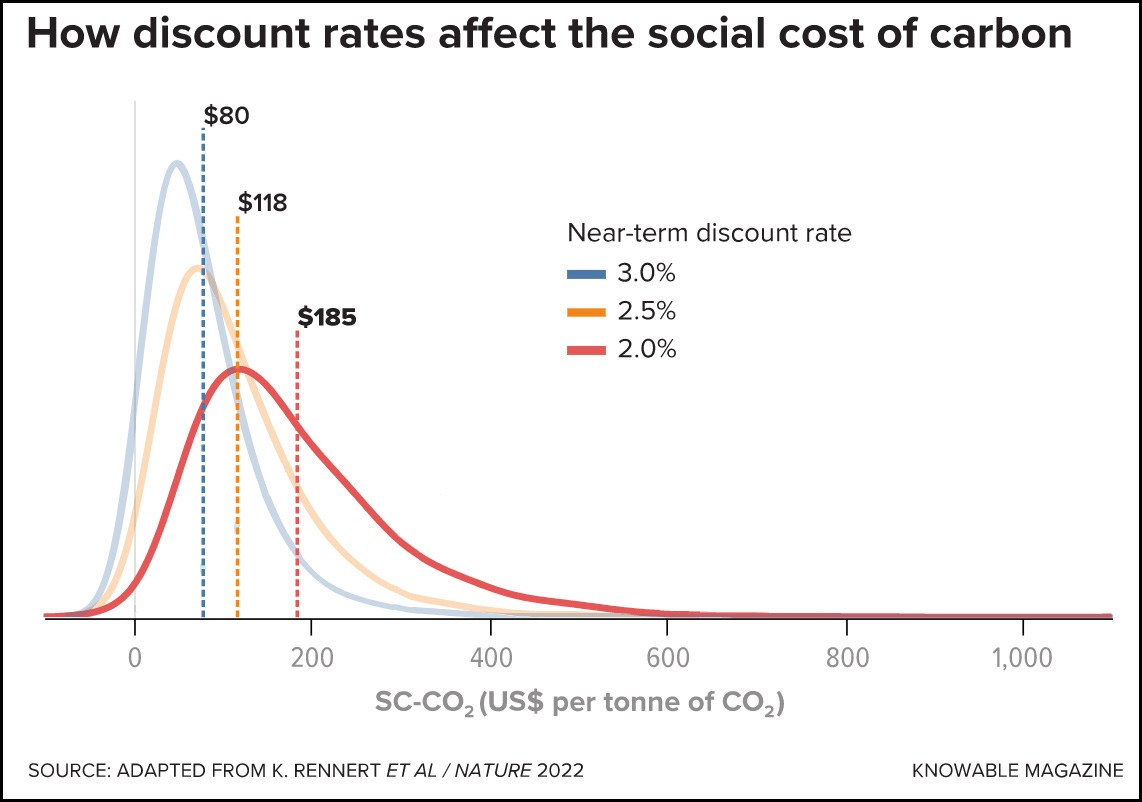

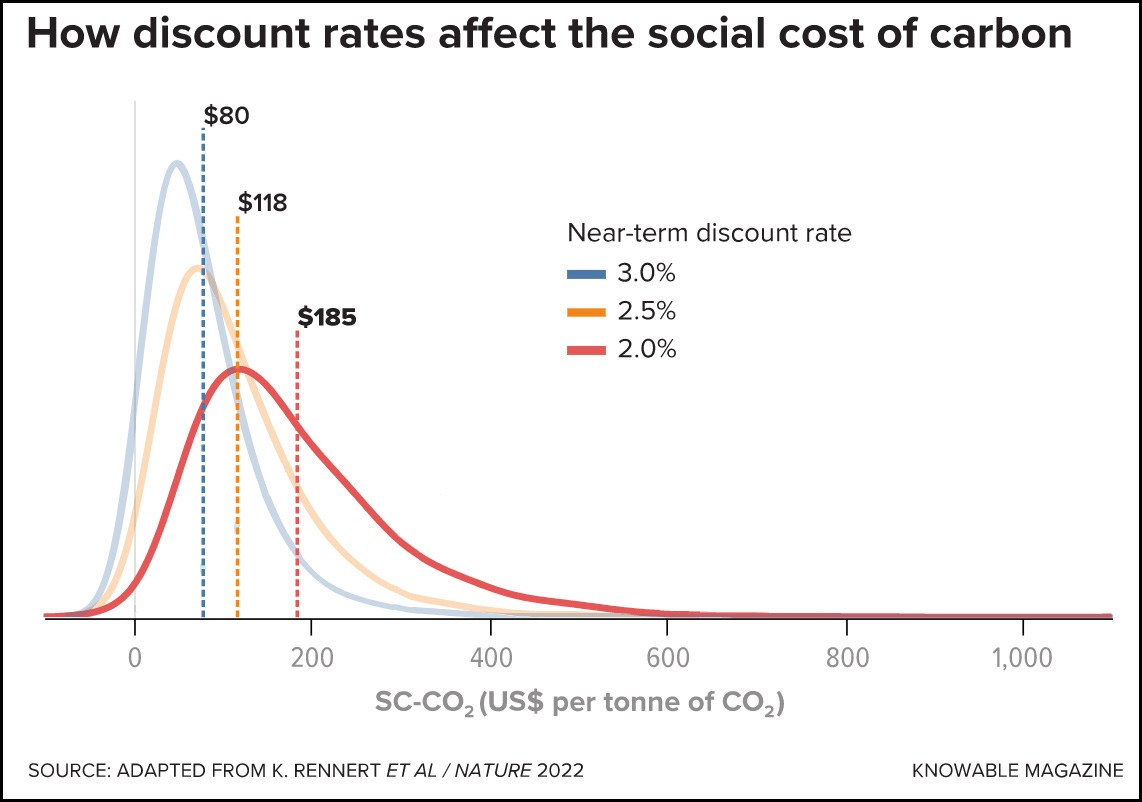

Why is this important? Because small changes in the discount rate can have big effects on regulation. In the area of climate change, for example, a lower discount rate means we're taking future effects more seriously, and that in turn means that regulations now (which have present-day costs) should be stiffer. Here, for example, is an estimate of how much we should tax carbon based on the future effects of global warming:

A discount rate of 3% implies that the social cost of carbon is only $80 per ton. A discount rate of 2% implies a cost of $185. The OMB's new 2% default rate means that cost-benefit analysis is more likely to come out positive for regulations on things like carbon and pollution, which have effects mostly in the future.

A discount rate of 3% implies that the social cost of carbon is only $80 per ton. A discount rate of 2% implies a cost of $185. The OMB's new 2% default rate means that cost-benefit analysis is more likely to come out positive for regulations on things like carbon and pollution, which have effects mostly in the future.

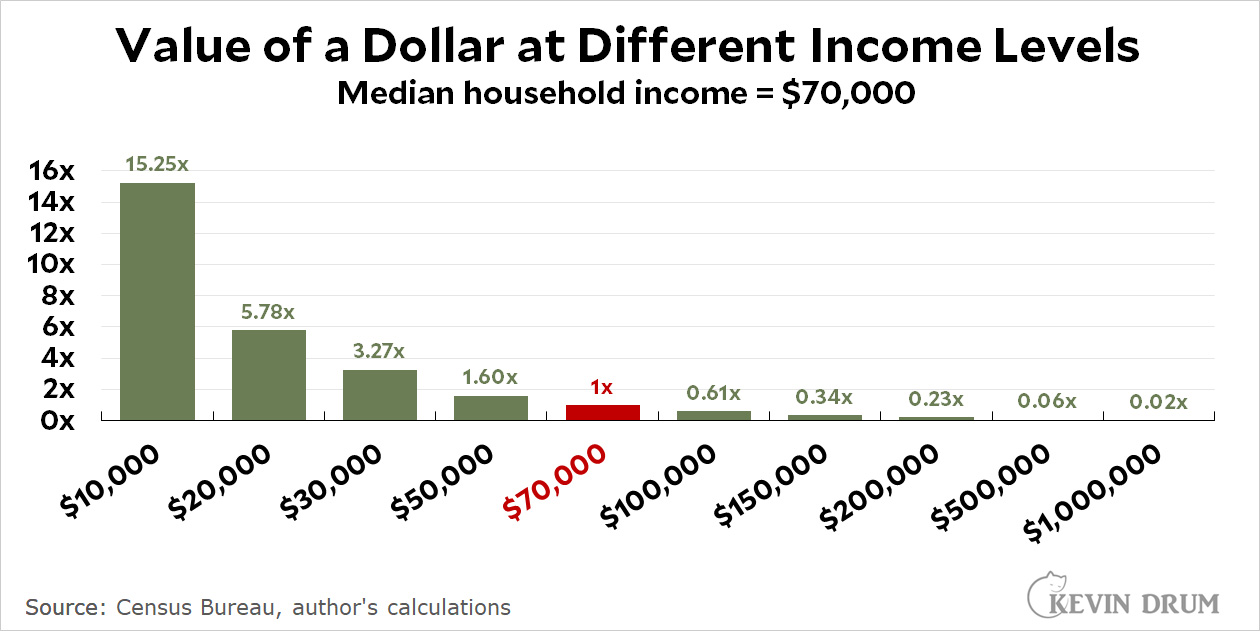

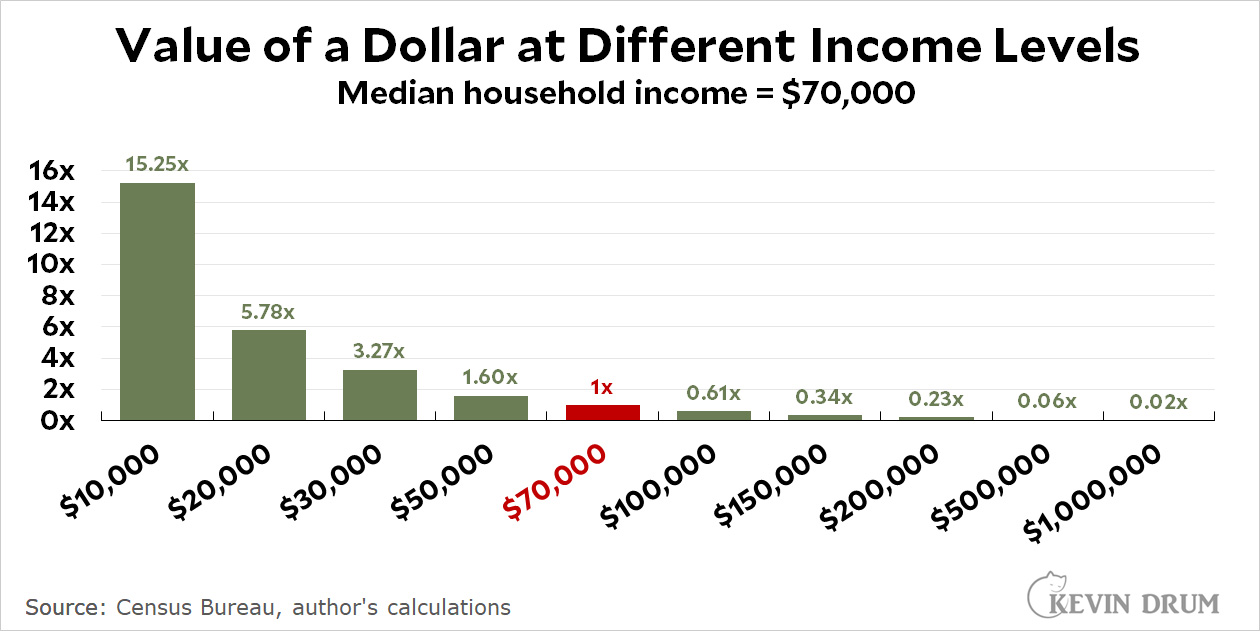

The second thing that Circular A-4 does is something I wrote about a few months ago when it was in draft form: it changes the way we treat different groups when we do cost-benefit analysis. In a nutshell, the new treatment assumes that a dollar is worth more to a poor person than a billionaire. So if some new regulation costs a rich person ten dollars but benefits a poor person ten dollars, it will now pass a cost-benefit analysis because that ten bucks means a lot more to the poor person than the rich person. Here's how much a dollar is worth to different income groups:

A dollar of benefits to the poorest group is now worth more than $700 in cost to the richest group.

A dollar of benefits to the poorest group is now worth more than $700 in cost to the richest group.

There's more to Circular A-4 (it's 93 pages long) but these are the two most important. Between them, they make it much more likely that cost-benefit analyses coming out of federal agencies will be both fairer and more reasonable.