Back when I was a tiny tot—let's say around 1990 or so—I learned that the Federal Reserve controlled monetary policy via open market operations that influenced short-term interest rates (the "fed funds rate"). High rates slowed the economy and low rates gave the economy a boost. The Fed pushed the fed funds rate up and down by buying and selling Treasury bonds on the open market.

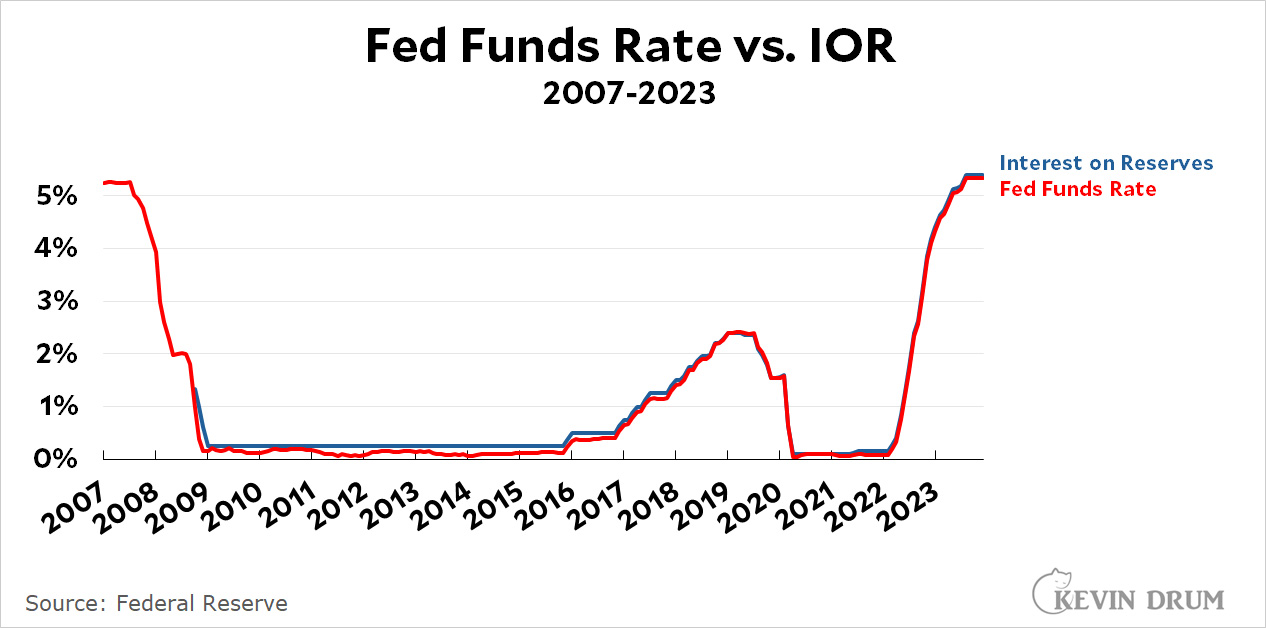

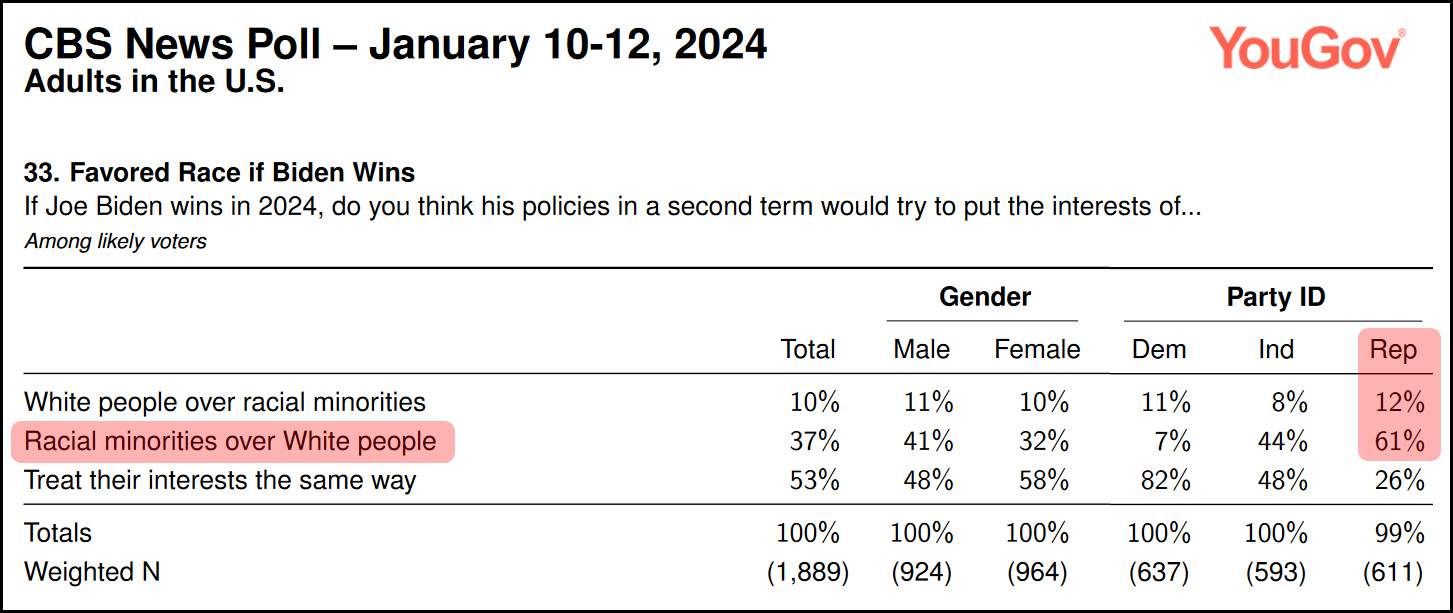

Today, Peter Coy comes along to tell me I'm way out of date. The Fed no longer relies on open market operations to influence interest rates. Instead, it just changes the rate it pays banks on their reserves. If, say, the Fed is paying 5.25%, then short-term bank rates will automatically increase to 5.25%. After all, if a bank can get that much just by letting its money sit safely at the Fed, why would it ever loan out money for less? Here's a chart that shows how both rates change in tandem:

In March 2022, the Fed started to raise the interest rate on reserves and the fed funds rate followed right along.

In March 2022, the Fed started to raise the interest rate on reserves and the fed funds rate followed right along.

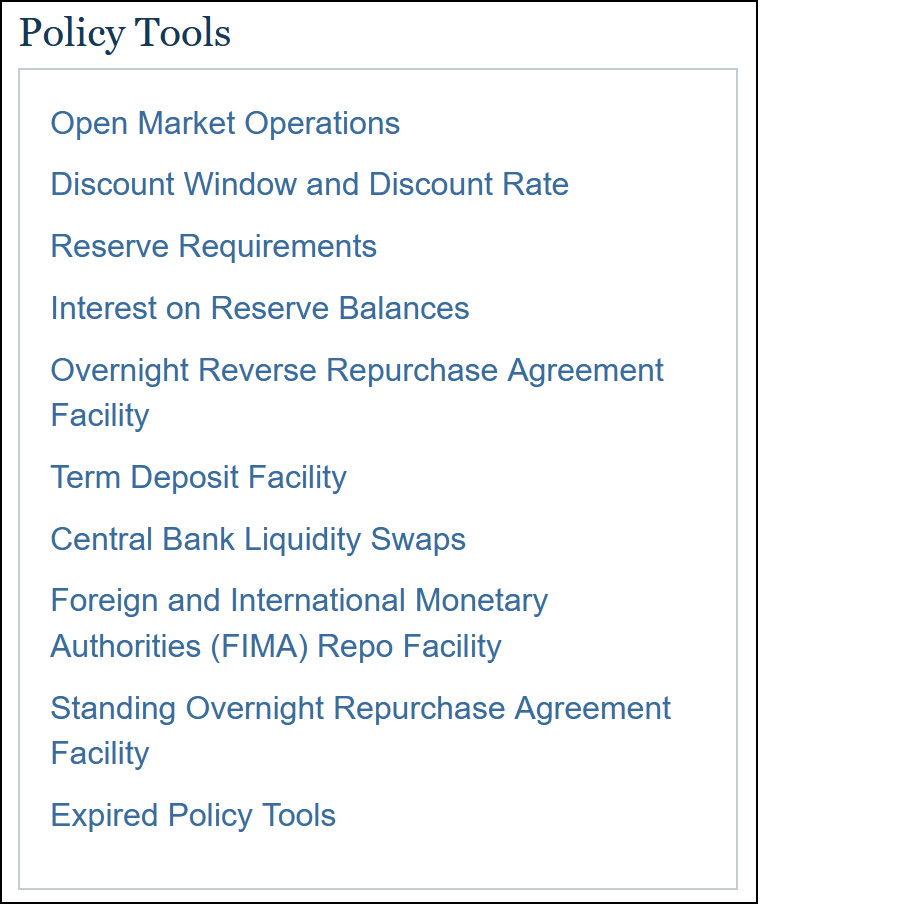

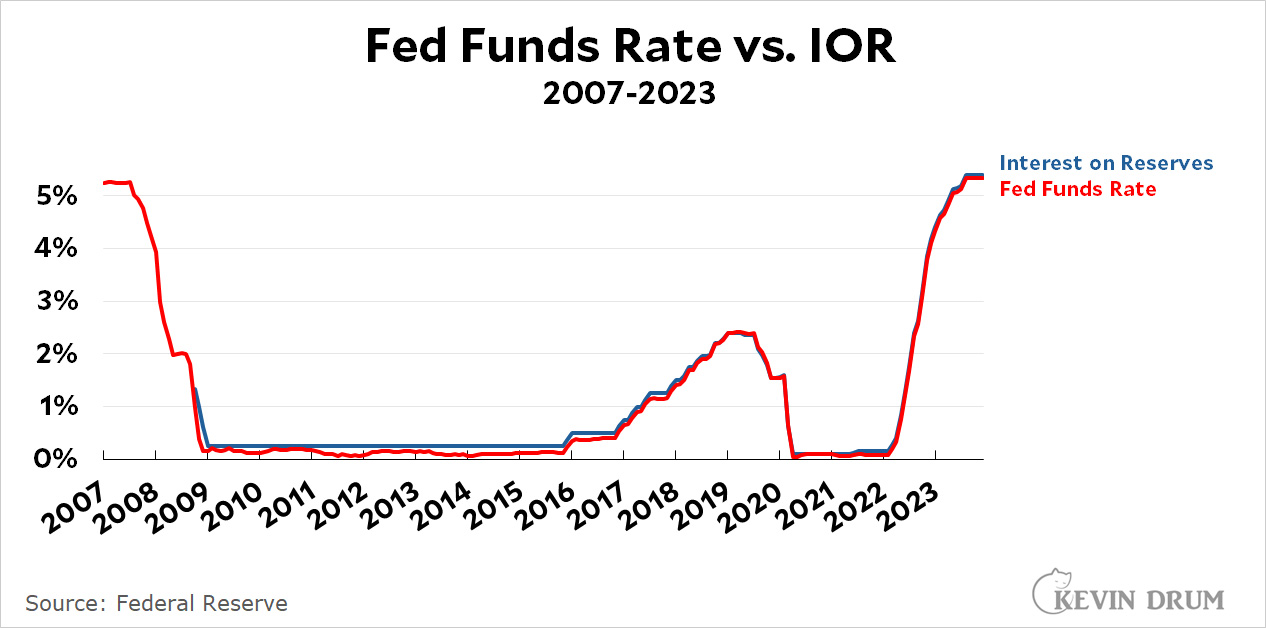

Coy wants to know why it's taken so long for textbooks—and all the rest of us—to get the message that things have changed. I may have the answer. For starters, here's what you see on the Fed's Monetary Policy home page:

You'll notice that "Open Market Operations" is still at the top and "Interest on Reserve Balances" is #4. If you click on these, open market operations are described as a "key tool" while interest on reserves is described as an "important tool." This doesn't exactly drive home the point that open market operations are dead.

You'll notice that "Open Market Operations" is still at the top and "Interest on Reserve Balances" is #4. If you click on these, open market operations are described as a "key tool" while interest on reserves is described as an "important tool." This doesn't exactly drive home the point that open market operations are dead.

There's also the Fed's Open Market Report, which says things like this:

The Federal Reserve implements monetary policy in a framework that includes a target range for the federal funds rate to communicate the FOMC’s policy stance, a set of administered rates set by the Federal Reserve, and market operations directed by the FOMC.

It's true that "administered rates" comes before "market operations" in this paragraph, but again, it's hardly a clarion call about open market operations being dead. There's also this:

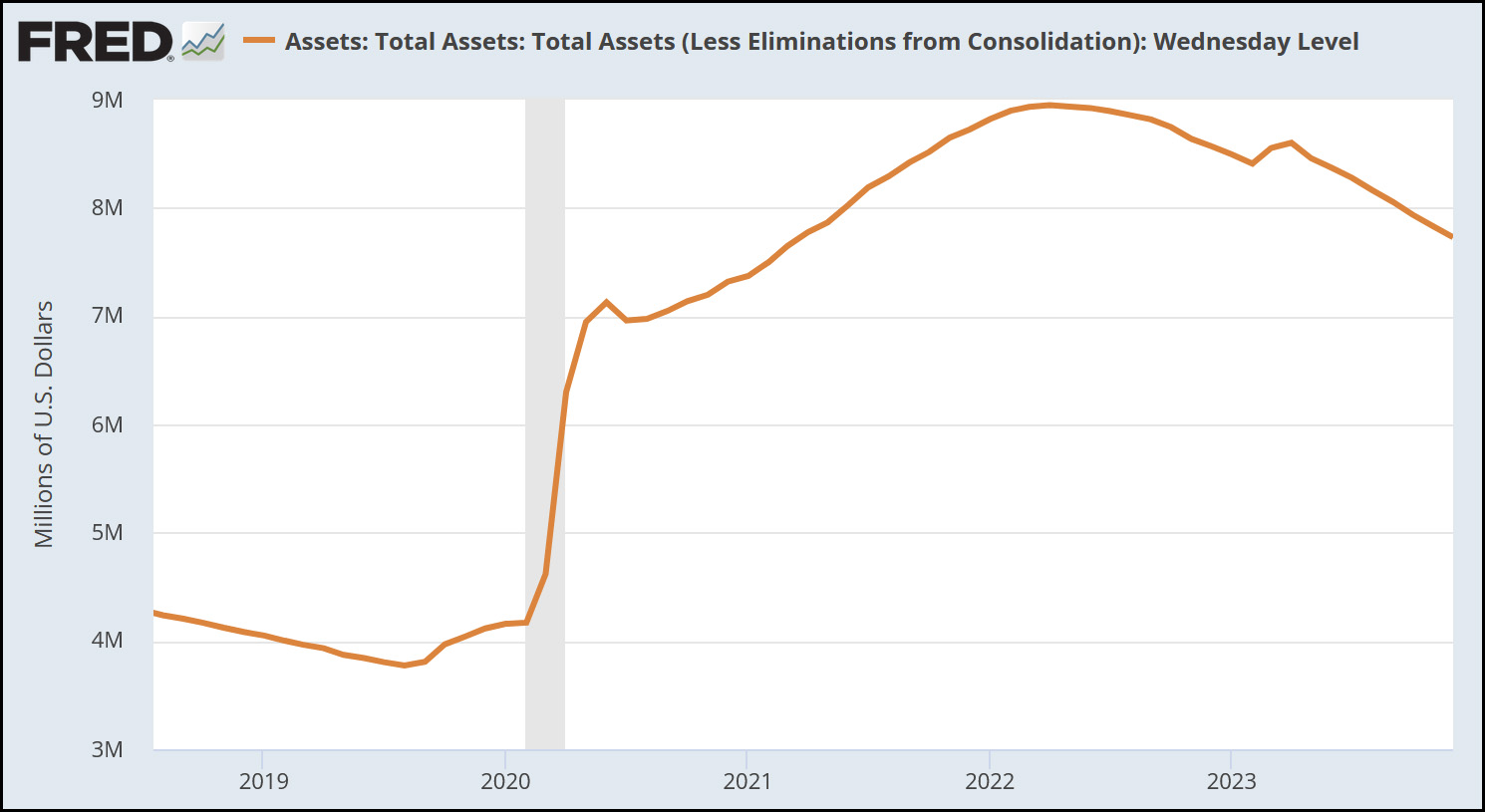

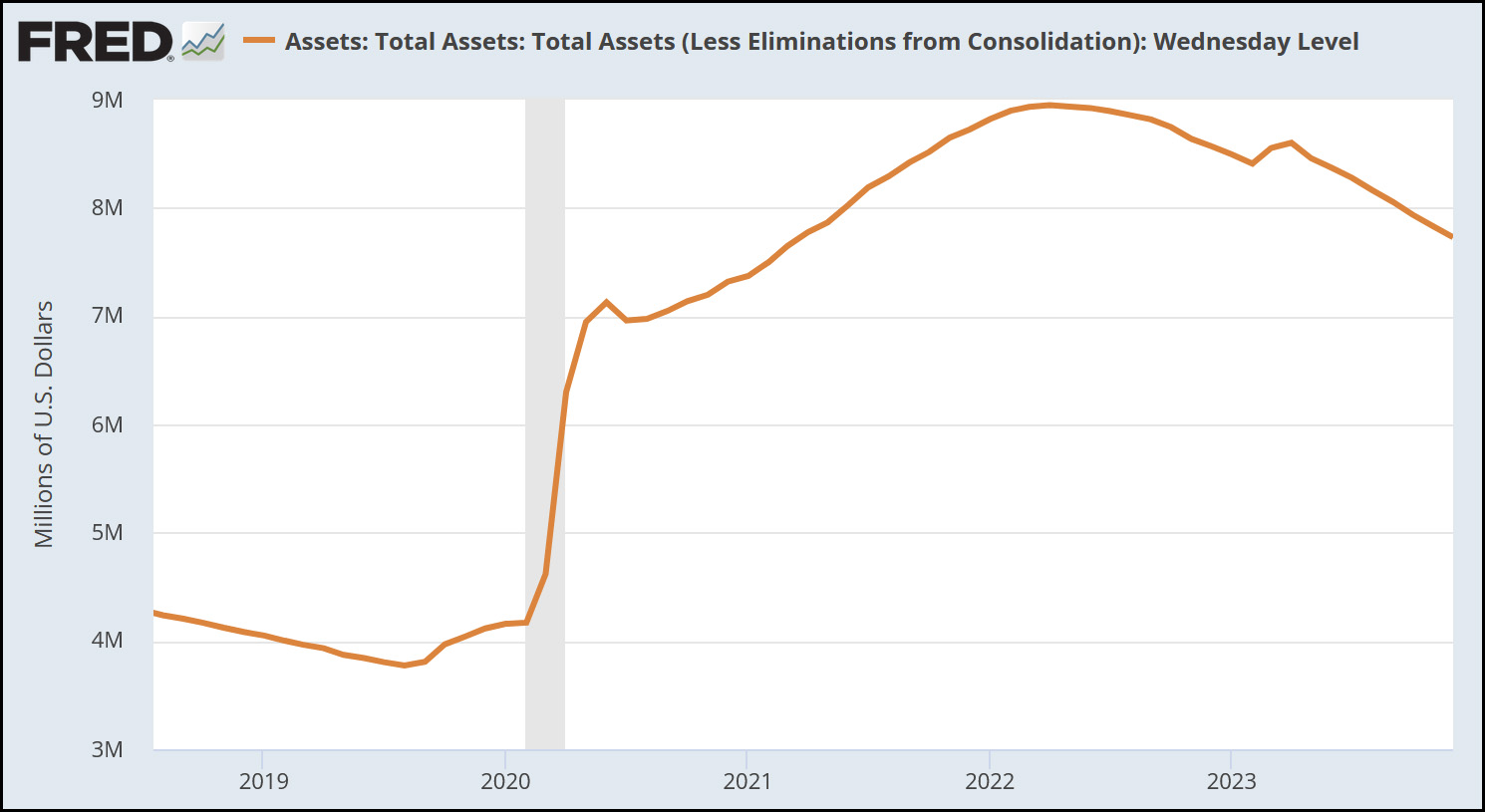

This is the Fed's balance sheet. As you can see, it went up considerably at the start of the pandemic in order to keep monetary policy loose, and then started to decline precisely in March 2022, when the Fed wanted higher interest rates. That's "quantitative tightening," which is a form of open market operation targeted at longer-term interest rates. So open market operations have changed, but aren't really dead.

This is the Fed's balance sheet. As you can see, it went up considerably at the start of the pandemic in order to keep monetary policy loose, and then started to decline precisely in March 2022, when the Fed wanted higher interest rates. That's "quantitative tightening," which is a form of open market operation targeted at longer-term interest rates. So open market operations have changed, but aren't really dead.

Finally, there's the question of what the Fed would do if the economy went sour. No bank will loan money for less than the interest rate on reserves, so the Fed can always force interest rates up. But what if they want to force interest rates down? Even if they reduce the reserve rate to zero, there's no way they can guarantee that banks will follow suit. It still might make sense for them to keep their rates higher than the Fed wants. If that happens, then hello open market operations! They'll be back.

Now, it's true that in 2019 the Fed said this:

The Committee intends to continue to implement monetary policy in a regime in which an ample supply of reserves ensures that control over the level of the federal funds rate and other short-term interest rates is exercised primarily through the setting of the Federal Reserve's administered rates, and in which active management of the supply of reserves is not required.

That's clear enough, and Coy is right that this is the company line for now. All I'm saying is that the Fed hasn't exactly shouted this from the rooftops. It's hardly any wonder that so many of us—even textbook writers!—have been a little slow to update our brains.

POSTSCRIPT: I feel like I have to add something here. If controlling the fed funds rate is as easy as changing the interest rate on reserves and then pressing Enter, why did the Fed ever do it differently? Open market operations are a helluva lot more complicated and labor intensive.