Ezra Klein has a long interview today about governance with Steve Teles and Jennifer Pahlka. The gist is that our government bureaucracies really are terrible and liberals are in denial about the need for massive reform. It left me with many thoughts because I think, overall, it hit the wrong targets.

It's hard to adopt just the right tone for this because, God knows, big bureaucracies have lots of problems and liberals aren't always willing to face up to them. I'm really not trying to be a big defender of the bureaucracy here. But maybe a little one? This turned out to be very long, so let's take it in small pieces.

KLEIN [on defending institutions]: The core conflict right now, the irresolvable one, the ones that two parties will not compromise on, is over institutions: Democrats staff and defend them. Republicans loathe and seek to raze them to the ground.

This is nothing new. Remember when William F. Buckley said he'd rather be governed by 2,000 random names from the Boston telephone book than the faculty of Harvard? That was 1963. As a possible explanation for the recent travails of the Democratic Party it really doesn't work.

PAHLKA [On the disconnect between policy and delivery]: Probably the biggest example of it would be the Biden administration’s insistence on the success of the big bills that were passed — the CHIPS Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, infrastructure, where they are incredible accomplishments legislatively. And if you look at it from that perspective, he is absolutely a hero. But if you look at from the perspective of people in states in the U.S. whose economies have been hollowed out: It took so long to get that money out the door.

This just isn't true. First, here's construction spending after the CHIPS Act:

That's fast! And despite lots of early warnings, new fabs have been opening on time and on budget. Second, here's estimated IRA spending on green energy projects:

That's fast! And despite lots of early warnings, new fabs have been opening on time and on budget. Second, here's estimated IRA spending on green energy projects:

This represents about two-thirds of the total authorized. It's going out the door and being used about as fast as you could hope for with such enormous sums.

This represents about two-thirds of the total authorized. It's going out the door and being used about as fast as you could hope for with such enormous sums.

Third, the infrastructure bill. The headline number is that it was a $1.2 trillion bill. But that's grossly misleading. It allocated only $550 billion in new funding, and as always, that's over a decade. It's really a $55 billion bill, and that money is being spent just fine.

KLEIN [on nothing ever getting done]: The first contract to build the New York subways was awarded in 1900. Four years later — four years — the first 28 stations opened.

Compare that to now. In 2009, Democrats passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, pumping billions into high-speed rail. Fifteen years later, you cannot board a high-speed train funded by that bill anywhere in the country.

So, yeah: I’m worried about our institutions. I’m angry at our institutions. I don’t want to defend them. I want them to work.

Well, yes, but I don't think this is due to dysfunctional liberal bureaucracies. It's due to a different liberal delusion: the unshakable belief that America desperately needs lots of high-speed rail. This has been going on for 60 years, not just 15, and we still have no high-speed rail.

The bureaucracy isn't at fault for this. It would happily dole out the money for HSR if it was truly a priority for anyone. But it's not. California is ground zero for HSR boondoggles, and only a part of that can be blamed on inefficient bureaucratic rules—though there are plenty of those. Mostly it can be blamed on voters and politicians who have succumbed to hazy liberal dreams of gleaming trains that have no basis in reality.

TELES [on why bureaucracies deteriorate]: Things go wrong. There’s a scandal. We add a new process, we add a new procedure — without really thinking about how it interacts with all the rest of it. And so we shouldn’t necessarily think that the problems that Jen is describing are a result of the fact that anybody designed this thing to operate this way. It’s really the result of just additional layers of accretion without corresponding layers of destruction.

This is true. When we set out to build things these days there are lots of hoops to jump through. The project has to be let out to competitive bidding. You have to write an environmental impact report. Maybe you have to ensure some of the work is done by small businesses. There are minority set asides. Buy American provisions. Zoning variances. Environmental justice requirements. Public comment periods for new rulemaking. Grievance procedures for anyone who's unhappy. Etc.

But with few exceptions these hurdles have nothing to do with the bureaucracy per se. They're put in place by legislators at all levels. Liberals want to ensure social fairness. Conservatives want to make sure liberal interest groups can't cheat. Local politicos want to retain power. And everyone wants to make sure nothing objectionable happens near their own house.

This is where the blame lies. Bureaucracies themselves are just the unlucky bastards who are forced to make it all work.

PAHLKA [on outside forces]: We’re skipping over a really important point here that Steve touched on when he mentioned scandal, which is the adversarial nature of all this.... Steve was referring to that earlier, sort of the ’60s and ’70s that’s still very much in our DNA as Democrats — that is to sue, sue, sue. Well, if we sue, sue, sue all the time for all sorts of reasons —

Suing government, here, you mean?

PAHLKA: Exactly. Suing the government. Then every time we sue, we make the government more risk averse. There’s a lot of adversarialism out there, and the natural result of that is going to be a system in which you defend your judgments by using no judgment.

No argument here. This is absolutely a problem—though it's pretty ecumenical these days. Block a rich person's view and they sue over some alleged deficiency in the EIR. Build something near a poor neighborhood and liberal interest groups will sue. Build near a residential area and owners will sue over increased traffic. Violate someone's notion of government overreach and conservative interest groups will sue. Award a contract and the losers will sue.

But—this is obviously a broad problem that bureaucracies themselves do nothing to cause. All they can do is react, and it's true that sometimes the reaction can be a sort of fetal crouch where dotting i's becomes far too important.

If you want to solve this, the answer lies mostly in legislation that rolls back protections a bit and provides safe harbors if the truly important rules are followed.

KLEIN [on the problems with big cities governed by Democrats]: I was looking at some election results. And it was weighting the shift in the vote by the density of the place. And what it shows is that in the most dense places, which is to say the big cities, the vote turned against Democrats the most... These are places where people were very exposed to blue state governance, exposed to the cost of living, exposed to housing crises, exposed to disorder on the streets, homeless encampments.

I doubt very much that this is responsible for a sudden shift over the past four years. More likely it's due to the fact that Kamala Harris didn't campaign in these places and lots of Democrats in deep blue cities stayed home because they knew their votes didn't matter. The obsessive coverage this year of the seven swing states as the only ones that mattered may have had something to do with it.

But I want to make a larger point. It's true that big cities have deteriorated over the decades, but it's a couple of big trends that are largely responsible for this. The first one is also the most obvious: Both the rich and the upper middle class have increasingly disengaged from cities, partly by moving to the suburbs and partly by segregating themselves into gated enclaves where they can shut out the problems of urban life. This has left central cities increasingly subject to the pathologies of the poor, the poorly educated, and the homeless.

Second, the poor communities themselves have deteriorated. In the past, the smartest and most capable of the poor stayed put their entire lives because no other options were open to them. They ended up as the natural leaders of these communities. But no longer. We've gotten too good and too aggressive at identifying these people and sending them to college—where they become part of the middle class and move away. As a result, central cities are left rudderless and even poorer.

These problems obviously have nothing to do with governance, either red or blue. It's just the way things are.

TELES [on the high cost of building stuff]: A piece by Leah Brooks and Zach Liscow...shows in exhaustive detail just how much the costs of building infrastructure in the U.S. have gone up, which Jen was talking about earlier. And they demonstrate that the explanation for that increase, which I think is behind a lot of Americans’ sense that nothing works, is citizen voice. That there’s so many opportunities for often quite minoritarian intervention in building things, that everything takes very long. It takes a lot more. And the other thing is government doesn’t get big wins that translate into trust and a willingness to invest it with new resources.

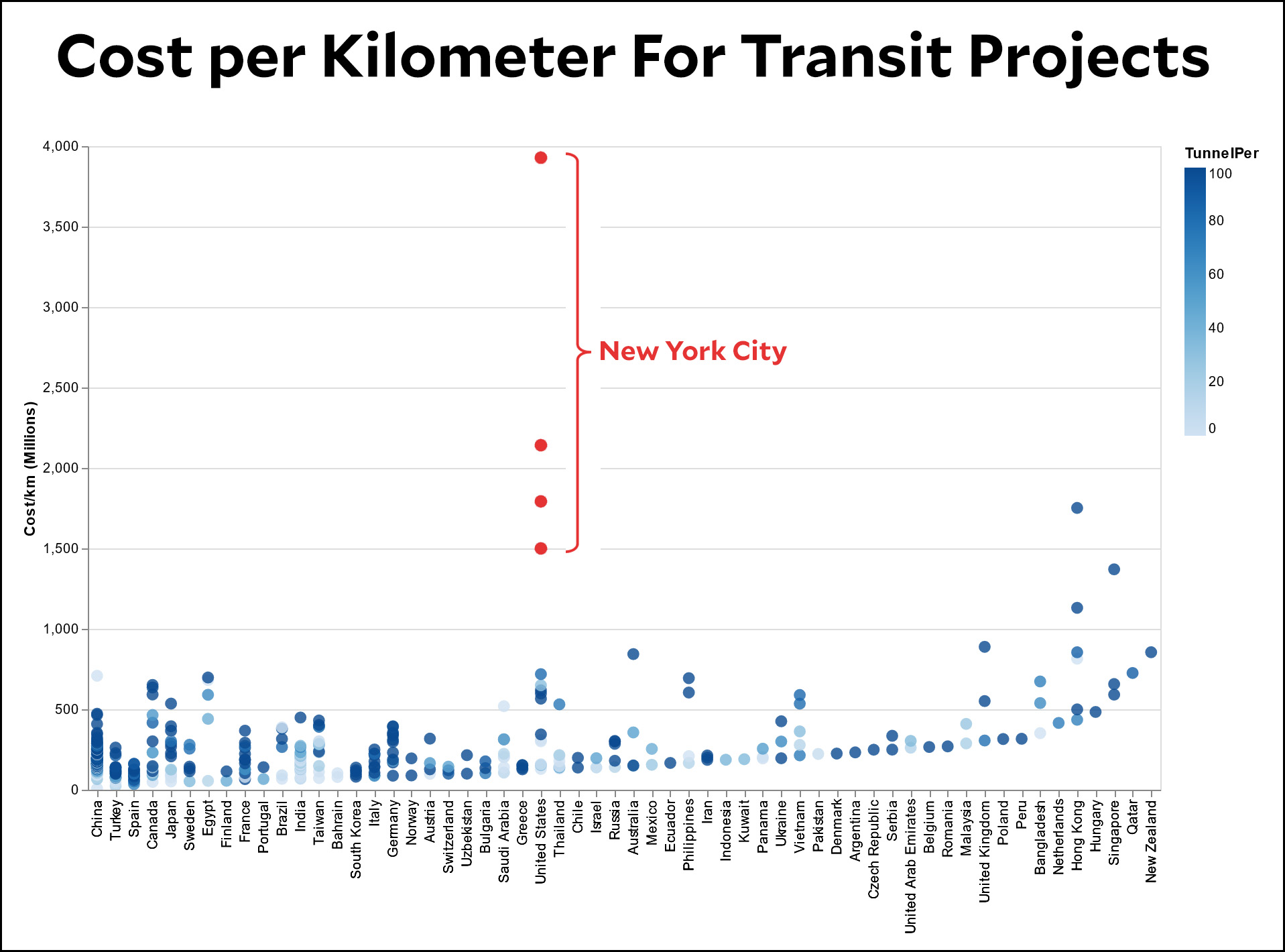

"Citizen voice." Not bureaucracy. Beyond that, though, I'm a big fan of this chart:

New York City has astronomical infrastructure costs. But more broadly, the US is fairly middling. There's a popular myth that America has fantastically higher building costs than other countries, but it's largely based on (a) New York City, which gets a ton of media coverage; (b) comparison of a few high-profile HSR projects; and (c) massive building throughout China, where the government doesn't have to care about public approval. Overall, though, it really is mostly a myth. There's probably a kernel of truth to it because America really is a litigious nation, but no more than that.

New York City has astronomical infrastructure costs. But more broadly, the US is fairly middling. There's a popular myth that America has fantastically higher building costs than other countries, but it's largely based on (a) New York City, which gets a ton of media coverage; (b) comparison of a few high-profile HSR projects; and (c) massive building throughout China, where the government doesn't have to care about public approval. Overall, though, it really is mostly a myth. There's probably a kernel of truth to it because America really is a litigious nation, but no more than that.

Here's a story: FEMA has long handed out money to disaster victims, but in the past they required people to spend it only on approved things. If you ran out and needed more you had to show receipts that demonstrated you had followed the rules.

Then they decided this was dumb and rescinded the rule. That's an example of a bureaucracy killing a regulation on its own. It can be done.

But it also opens up FEMA to blowback. Someday an activist group is going to collect evidence of fraud and hand it to a friendly politician, who is then going to demand hearings that generate blaring headlines about millions of wasted taxpayer dollars. You can practically see it in your mind's eye already.

And it's not as if the criticism will be wrong. You'd like to think that people could be relied on to use common sense, but they can't be and we all know it. It would be nice, for example, if all we had to tell restaurant managers was, For God's sake, just make sure the place is clean and the refrigerator works and employees wash their hands. But as we become richer we also become more risk averse. That means lots of detailed rules—the refrigerator must close automatically and contain separate areas for meat and vegetables and run at 34-36°F and shelving must be stainless steel. This is not the bureaucracy at work. This is the result of the public reading The Jungle and Silent Spring and Food Politics and demanding action. But that's not all. At the same time we also demand that cheating can't be allowed. And the environment be kept clean. And the workplace be safe. And residents have some say in what gets built next door. So we demand politicians pass some rules about this and naturally they do what they're told.

This doesn't always turn out the way we'd like. But it's not really the fault of the bureaucracy. For that, we just need to look in the mirror.

Aside from recreational marijuana, drug use is down for all age groups.¹ Ditto for alcohol abuse.

Aside from recreational marijuana, drug use is down for all age groups.¹ Ditto for alcohol abuse.

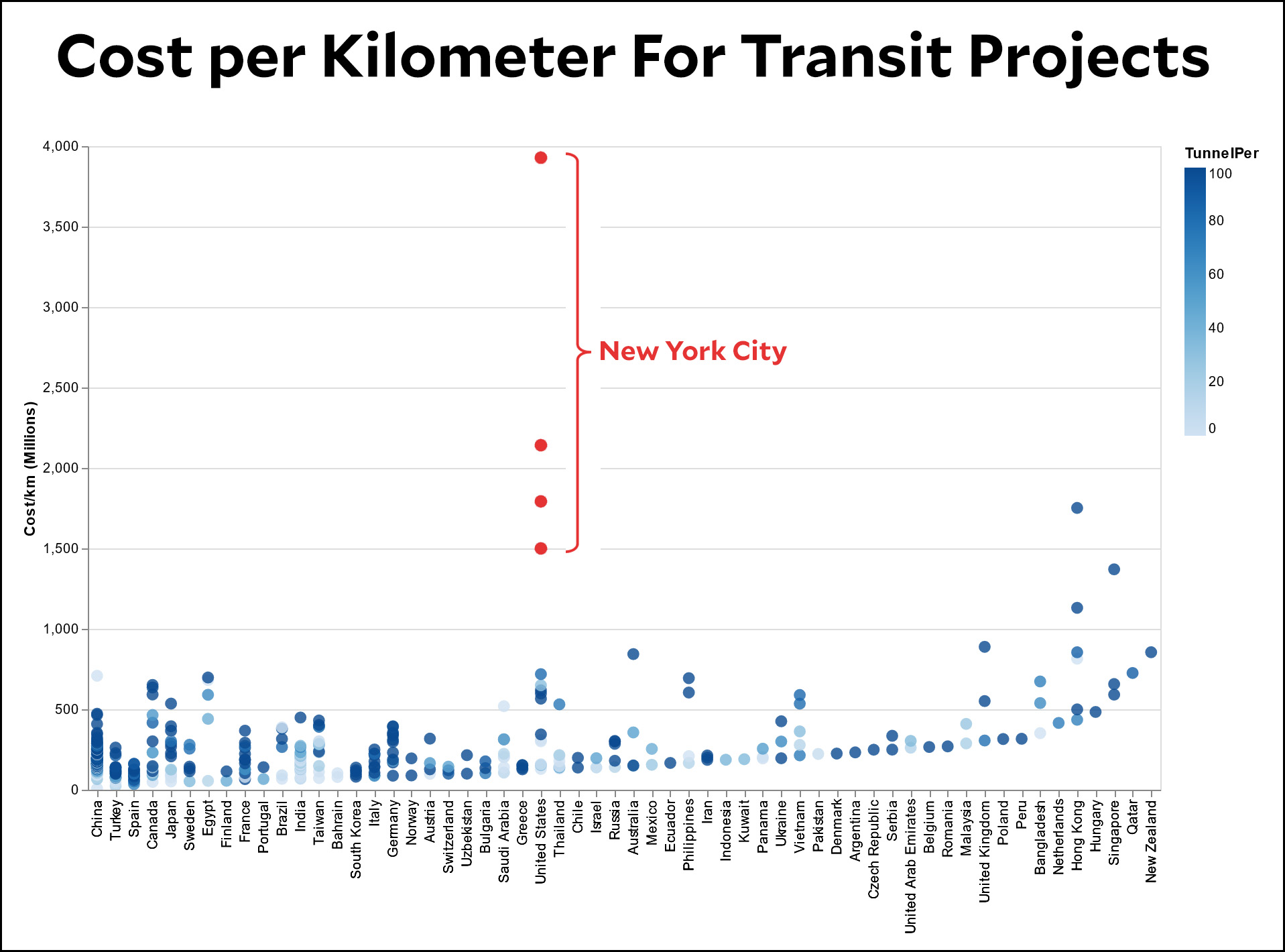

Thanks to lower lead poisoning among children, antisocial behavior of all kinds has dropped dramatically among teens:

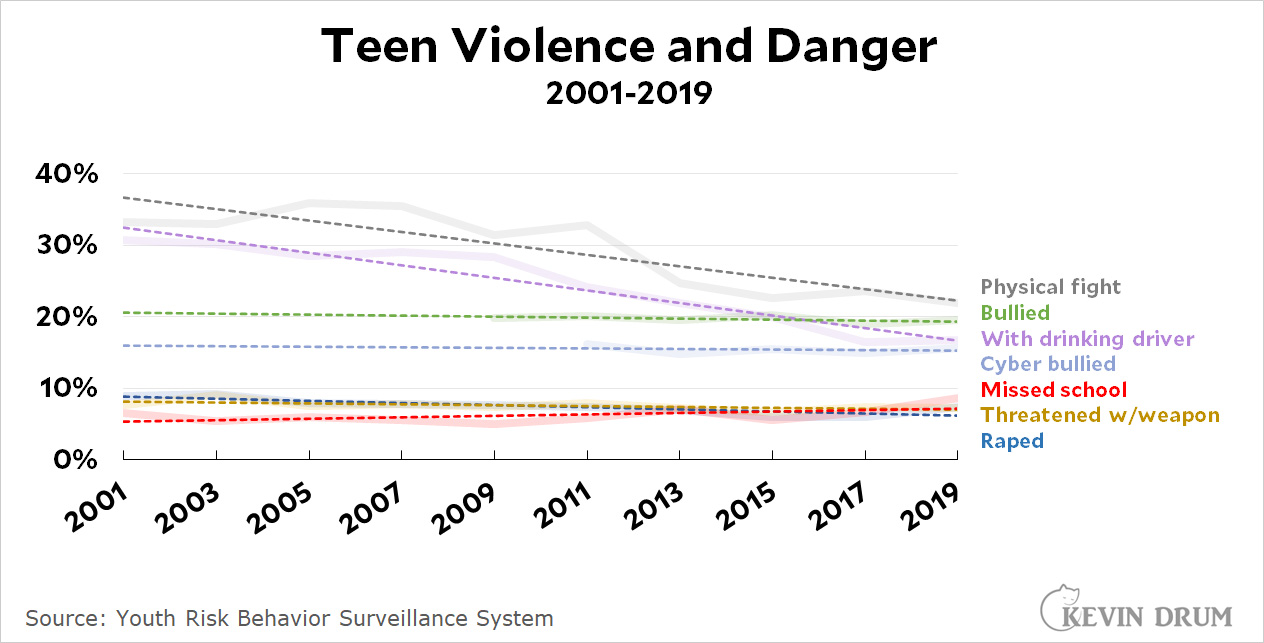

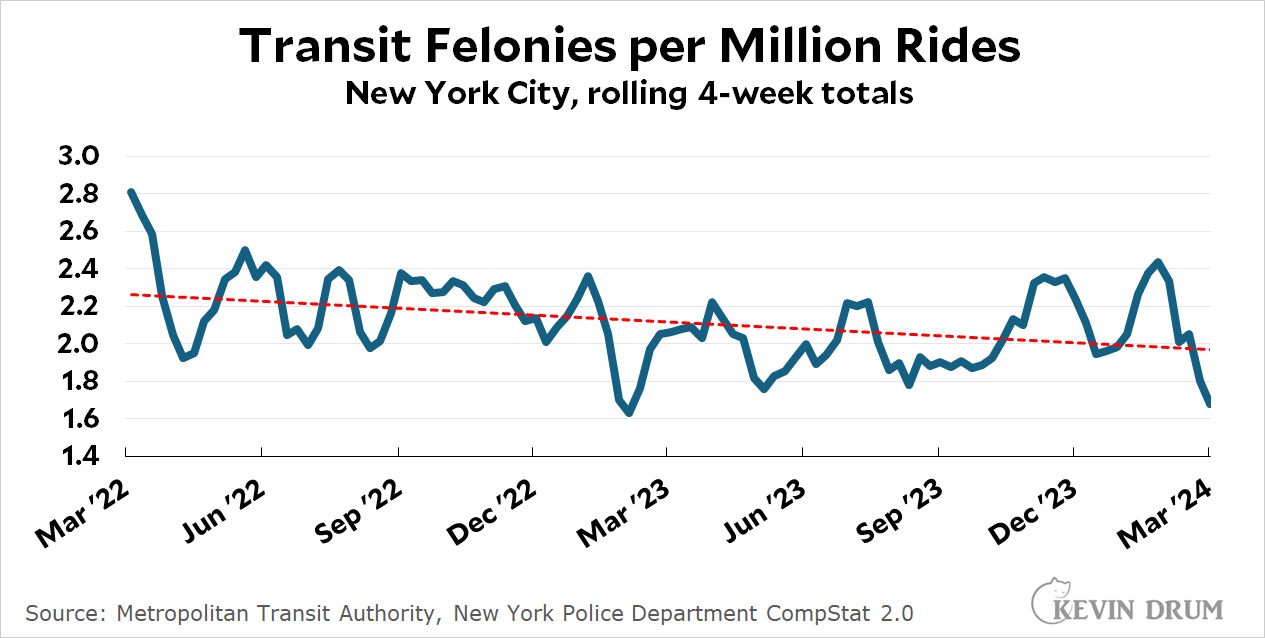

Thanks to lower lead poisoning among children, antisocial behavior of all kinds has dropped dramatically among teens: Add this all up and homelessness is mostly down; drug use is down; teen behavior is better; plus incomes are up and poverty is down. None of this means public disorder hasn't increased. But it does mean it would sure be mysterious if it has.

Add this all up and homelessness is mostly down; drug use is down; teen behavior is better; plus incomes are up and poverty is down. None of this means public disorder hasn't increased. But it does mean it would sure be mysterious if it has.

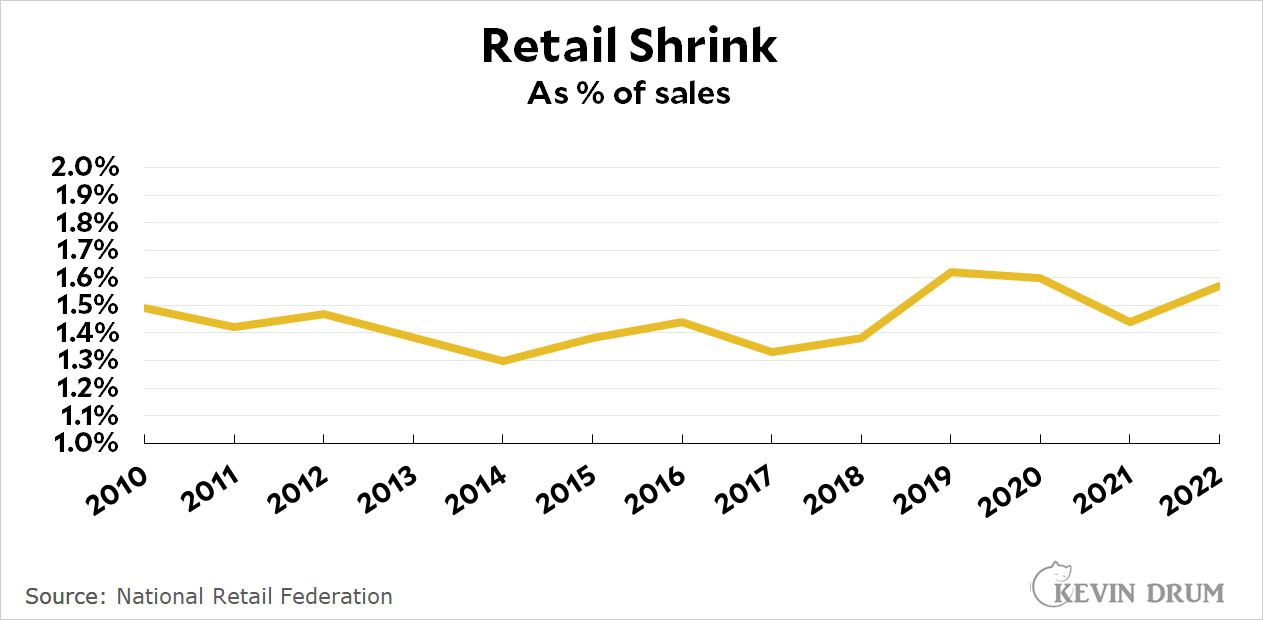

Ruthless shoplifting gangs terrorizing drug stores and supermarkets are in the news regularly, but retailers themselves don't report any rise:

Ruthless shoplifting gangs terrorizing drug stores and supermarkets are in the news regularly, but retailers themselves don't report any rise: Anecdotally, Charles Fain Lehman visited Chatanooga and reported back: "Even as violent crime has largely receded, there are multiple indicators suggesting that another problem persists: disorder." But if you read his very detailed piece, there's not much there. Even minor crimes are mostly down over the past couple of years.

Anecdotally, Charles Fain Lehman visited Chatanooga and reported back: "Even as violent crime has largely receded, there are multiple indicators suggesting that another problem persists: disorder." But if you read his very detailed piece, there's not much there. Even minor crimes are mostly down over the past couple of years.