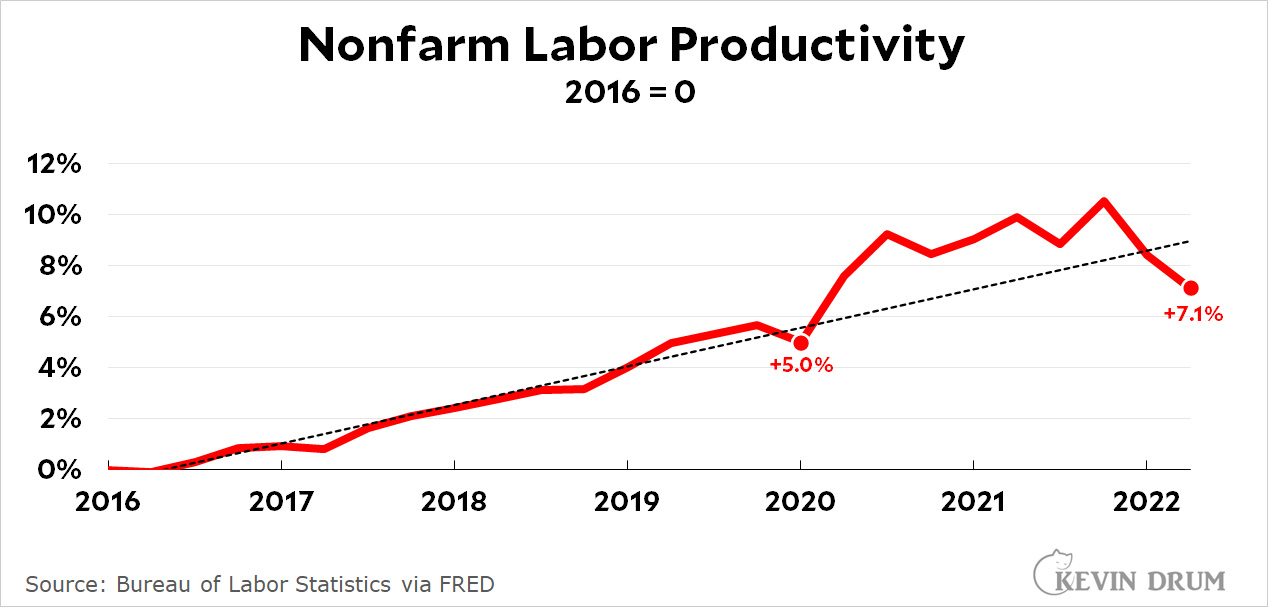

The BLS released productivity numbers for Q2 this morning, and the headline number is bad: a 4.6% decline from the previous quarter (at an annualized rate). This is bad, but in a slightly different way than it seems. Here's a chart that shows the absolute level of productivity, not the change from quarter to quarter:

This is, as usual, my favorite format. First I draw productivity from 2016 through the first quarter of 2020, just before the pandemic. Then I draw a trendline. Then I fill in the numbers from 2020 to the present.

This is, as usual, my favorite format. First I draw productivity from 2016 through the first quarter of 2020, just before the pandemic. Then I draw a trendline. Then I fill in the numbers from 2020 to the present.

What you see is that productivity went up faster than trend during the pandemic. This is because a huge number of people were laid off. Total output went down, but the number of workers went down even more. By simple arithmetic, this means that output on a per-person basis was higher than before.

As the pandemic eased, the opposite happened. Output went up, but the number of workers went up even more. The same arithmetic tells us that this means output on a per-person better declined.

There's nothing especially wrong with that. We should expect productivity to return to trend level once the economy has recovered. The problem is that this happened in the first quarter. But then, instead of leveling out, productivity declined again, taking us well below the pre-pandemic trend.

It's typical of recent recessions that productivity continues to go up or, at worst, stays flat. Usually, however, productivity keeps going up after the recession is over. This happened again this time, but only for a couple of years before it began to turn down. This is only the second time in 30 years that productivity has decreased two quarters in a row (the other time was in late 2012).

This is yet another indication of how strange the economy is right now: GDP is declining even as employment keeps going up. This is not usually how a recession works. (Nor is it how an expansion works.) So everyone is puzzled.

Here's one explanation that will probably ruffle some feathers: unemployment is too low. Employers have been snapping up anyone with a pulse, and this means they're pulling relatively unproductive workers off the sidelines. Many of them are now now stuck: hiring more people doesn't really improve output because the new workers are of such poor quality. They require more management time and more cleanup time after mistakes than they're worth. Maybe the conventional wisdom was right all along: 4% unemployment really is about the lowest it should ever get in an advanced economy like ours.

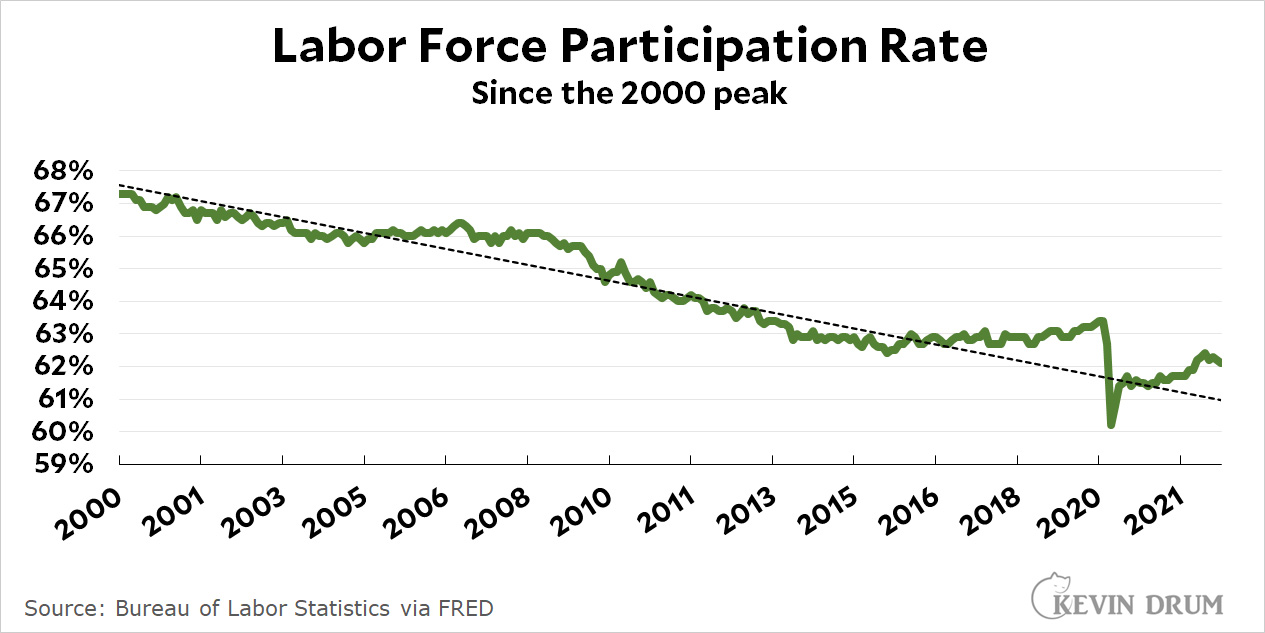

The way to return to growing productivity, as usual for the past century, is more machines. But things have changed. When the Industrial Revolution started, the productivity increase from automation was so great that we needed as many workers as before just to handle the huge increase in output. Lately, though, that hasn't been true. Automation has produced modest increases in productivity and the number of workers needed to handle the higher output has gone down. You can see that in the fact that the labor force participation rate has declined from its peak of 67% in 2000 to about 62% today. Here's what that looks like in a slightly modified version of my favorite format:

This time I drew the trendline through 2016, which shows a steady decrease in labor force participation. But then the participation rate flattened and even moved up in 2019. There was a huge downward spike during the pandemic, but the recovery put us right back on trend. Starting in 2021, however, participation grew well above trend.

This time I drew the trendline through 2016, which shows a steady decrease in labor force participation. But then the participation rate flattened and even moved up in 2019. There was a huge downward spike during the pandemic, but the recovery put us right back on trend. Starting in 2021, however, participation grew well above trend.

Perhaps it grew too much. Perhaps employers have been more reluctant this time around to replace workers with automation. But that's not likely to last. For the first time in quite a while I saw a movie on Sunday and there were no ticket sellers at all. The entire process at our local gigantic multiplex was handled by touch screens. Fast food restaurants are moving in the same direction. The eventual result is going to be fewer workers but a return to normal productivity growth.

This is our long-term future and we can't avoid it except for short periods here and there. We're apparently in one of those periods now, but we'll probably return to trend before long. That means some pain in the employment rate, which the Fed seems determined to make even worse, but eventually a return to normal labor participation and productivity rates.

One of these days employers might be forced into (gasp) developing training programs.

"The entire process at our local gigantic multiplex was handled by touch screens. Fast food restaurants are moving in the same direction."

This might work for experiences and food preparation. After all, unless you really paid (have a receipt/ticket), you aren't going to get past the "gatekeeper" at the counter/ticket taker stand.

But automation at the Amazon Fresh stores that have opened here in northern Virginia is terrible from an owner's perspective.* I have yet to visit the Amazon Fresh near me with its lack of cashiers and have it correctly charge me for all the items I've picked up and walked out with. Like on the order of $20-30 loss to Amazon each visit. I'm not even trying to steal from them, and the technology still lets me do it... just wait until people figure out how to steal from them on purpose.

*Yes, I realize Amazon has more money than it knows what to do with, and so it doesn't really care about shrink loss. I know this because you don't get your receipt for up to a full day (wtf?!) after you leave so there's no way to tell if you're shoplifting or not on the day you visit, and I tried returning to Amazon Fresh after the first time it happened and had the one person working up front tell me to not worry about it. But Amazon's model of grocery shopping isn't going to work industrywide - most grocery store chains don't have the profit margins to lose $20-30 in product to each customer.

It seems unlikely the technology won't improve.

But we're always going to need people for the security piece. We won't entrust that machines. The moment a machine got it wrong and targeted a person who was not stealing the hew and cry would echo around the world. For similar reasons it's wildly unlikely we'll ever have 100% self-driving cars (as opposed to cars with an auto-drive feature similar to auto pilot in airplanes)

For similar reasons it's wildly unlikely we'll ever have 100% self-driving cars

I'm not sure we don't have them now, never mind that we won't "ever" have them. The fact that governments haven't approved them for all uses doesn't mean we don't have them. I know they're being used on a small scale in the SF Bay Area, and on a somewhat larger scale here in Beijing.*

I see it just the opposite: it's wildly unlikely 100% self-driving cars won't be with us at some point in the future. Statistically, once they're significantly safe than human drivers, the momentum will become overwhelming.

*They haven't come to my neighborhood yet, but I opt for one in a heartbeat over the hair-raising experience that is being a passenger in a Chinese cab. Relatedly, if you knew a human-driven tax was 200x more likely to get into an accident than a fully self-driven one, which one would you opt for? And that's before we get into the possibilities of eliminating violence on the part of human drivers—an all too common phenomenon, especially for female passengers.

"Some time in the future" takes in a lot of territory: millions, even billions, of years. Let me amend my statement to stipulate "in the foreseeable future".

Interesting. I did Amazon Fresh deliveries for a bit during the pandemic but switched to Giant pickup because I like what they carry better. I haven't been to the new Fresh stores because the two NOVA locations are too far away from me.

When the Industrial Revolution started, the productivity increase from automation was so great that we needed as many workers as before just to handle the huge increase in output. Lately, though, that hasn't been true. Automation has produced modest increases in productivity and the number of workers needed to handle the higher output has gone down.

The seems very paradoxical. Why would it be the case that a period of high productivity growth (industrial revolution) increased demand for human labor more than a period when productivity has been increasing more modestly? (recent times). Intuition suggests when machines are making huge strides, human labor tends to get left in the dust.

And the "fewer workers are now needed to handle the higher output" seems a bit shaky to me as an explanation. because there doesn't seem to be any particular reason consumers and businesses wouldn't want to buy more services.

(I should add: this very much is my talking—or rather, writing—my way through my own puzzlement rather than a pushback at what Kevin has posted here.)

The Industrial Revolution not only increased output of manufactured goods, it reduced the cost of those goods. People could buy more stuff, i.e. overall demand increased. This was true even early on in the Industrial Revolution, even though wages did not rise significantly. Later on, as labor gained bargaining power and wages rose, demand went up faster. As expenditures on necessities have declined as a proportion of spending, discretionary spending has gone up; satisfying the demand for non-necessity goods and services means employment for the people supplying them.

Britain had an empire that served as a captive market for its goods. The prices went down as productivity rose. This new market let British employers hire more local workers even as automation displaced others.

Of course, the wages were near subsistence and sometimes lower. This led to political violence and repression, though, starting in the 1830s, there were a variety of reforms. As historians point out, it was in the 1950s that the queen started recognizing centenarians.

True, but a market isn’t just people, it’s people with money to spend, money they had to earn from employment, producing stuff to sell to their compatriots, or to the mother country. The Industrial Revolution wouldn’t have been a Revolution had not an increasing number of workers, at home and abroad, risen above subsistence level, and thereby been able to purchase the increasing abundance of goods.

Here's a Twitter deep dive on some of these issues by Obama's CEA Chair, Jason Fuhrman, if anybody's interested:

https://twitter.com/jasonfurman/status/1557002113472937985

Two thoughts

1) Is it surprising that a deadly pandemic that has killed millions and caused long term health problems for tens of millions more would lead to slightly lower productivity growth during the pandemic?

2) I believe that the Covid recession caused a pretty massive decrease in capital inputs in 2021 and early 2022. Reasonable decision by lots of business owners given the uncertainty of things in 2020 and early 2021....but not likely to continue going forward.

A very large fraction of the people who died from Covid were not in the work force to begin with. Covid is not the Black Death.

Sure...but so what?

The number of people that dropped out of the labor force due to covid related issues was substantial.

The number of people who were seriously ill was massive.

The impact of school closures and sick family members was massive+substantial.

Many people previously attached to the labor force did die.

Also, we aren't seeing a massive change in productivity that needs a black plague event to explain.

I had Covid twice. It sucked, though it did not qualify as the sickest I'd ever been (that was a case of antibiotic reisistant pneumonia when I was 14). I was off work for a week each time-- and I work from home so isolation was not the reason for that. But it did not take me out of the work force long term; most people my age and below had the same experience.

I do not offer this as a callous statement, but a non-working 8-0 year who died of Covid was not part of the productivity stats to start with, so his death would not have had an effect on them.

Don't discount the impact of COVID on the workforce. Some people died, mainly poorly paid "essential" workers, often members of ethnic minorities. There were also a lot of older people who weren't all that keen on catching COVID and left the workforce earlier than they had planned. Then there was the problem of people being out sick with COVID disrupting schedules. I'd be shocked if COVID didn't have an impact on productivity.

Kevin often gets hung up on trendlines, but they are seldom predictive. If you really want to predict things, especially the future, you have to understand all the factors involved and know how they will change, and nobody knows this. Productivity is especially tricky as it is strongly affected by cyclic hiring trends as well as special factors that were involved in the pandemic. There is no such thing as "normal" productivity - that is you can't predict the future from past trends.

One thing that is often overlooked is that the huge increase in productivity of the industrial revolution was largely a matter of replacing human, animal, wind and water power with fossil fuels. If non-fossil energy can't completely replace fossil fuels both productivity and growth may be on a different trajectory.

I think it is more likely that the unique features of the current situation, (slowly-abating pandemic + commodity-supply problems due to war) have exposed flaws in the measures economists use. Contra Kevin, skill and motivation are not very significant factors determining productivity. Goods are produced, and services delivered, by systems of humans, machines, facilities and processes - the design of the system is the most significant factor. The laziest lumberjack driving a tree harvester will far outperform the most industrious lumberjack with an axe. Systems evolve over time; it would be very unusual for a less productive system were to replace a more productive one.

It is true that a new hire will likely not be as productive as one with more experience, but the percentage of recent hires in the workforce is too small, and the productivity difference not large enough, to account for a change as large as in Kevin’s plot. It is an artifact.

This reminds me of an older mystery, do anyone ever figure out why computers becoming ubiquitous didn't effect productivity? An old article for reference

https://www.computerworld.com/article/2798669/do-computers-improve-productivity-.html

From quoteinvestigator:

Thought for Today: “To err is human but to really foul things up requires a computer.” —Paul Ehrlich , American scientist (1926- )

How many more distractions to computers provide at work???

"You can take my cat videos when you pry them from my carpal tunneled fingers" -- Me

😉

On boarding takes longer now than in the before times....not to mention the burn out those working through the pandemic have suffered, and are now taking some time for themselves to recover

The other is: Alot of people changed careers in the shuffle.

Which means they need more training time. Hence being less productive than the workers they replaced.

Also, some productivity is fake; pushing workers to work more hours, wage theft, etc. That shows up as 'productivity' in the macro numbers, but cleaning it up with better labor practices makes 'productivity' seem to sink.

I think what we have to come to grips with is that due to the techno-revolution that our entire concept of work force participation may be warped. Although, it did happen just at the right time

No one expected a pandemic. Not one economist or presidential advisor saw it coming. It fundamentally changed the way "we" look at working. For many of us aged 62 and above we decided the risk of COVID outweighed the reward of working. So many of us went from producers who also consumed, to consumer ONLY. We were anticipating a gradual shift to this paradigm, but COVID was a catalyst to speed this up. When we look back at COVID and the work force we will find out that many people out right retired completely. Many more went part time

But when we looked forward from the 1970s to the 2020s we had no internet, no Uber, no door dash, relatively few gyms and spas. We were all busy doing other things. Not only have we become more technical we also became more basic. Its now better to have food delivered than it is to sit down in a crowded restaurant surrounded by coughing people who are complaining about sore throats. Take a look at all the airline cancellations of late. No crews, no planes.

This will take about a decade to straighten out

Folks quibbling about whether illness/COVID is a factor may try referring to https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNU02006735 and related work absence series.

The absence rates are up ~40% since start of pandemic and have not fallen despite a rise in employment. There are also marked spikes with each COVID surge.

Anecdotally as I watch teammates and families grapple with the impact of COVID and quarantine, I would be shocked if this couldn't explain a few % of productivity loss. I find that more likely than the "next marginal worker is 4% lazier" hypothesis.

Totally makes sense.

Thanks for this. I noted also that the chart is for ‘own illness’; so people who were not at work because they were caregivers, or were not reporting to work because they were exposed, would add to that total. To the extent that absences were paid, they add to economic input but not output, which is exactly what reduces aggregate productivity.