The Washington Post is worried that we're all getting lazy:

In the first half of 2022, productivity — the measure of how much output in goods and services an employee can produce in an hour — plunged by the sharpest rate on record going back to 1947, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The productivity plunge is perplexing, because productivity took off to levels not seen in decades when the coronavirus forced an overnight switch to remote work, leading some economists to suggest that the pandemic might spark longer-term growth. It also raises new questions about the shift to hybrid schedules and remote work, as employees have made the case that flexibility helped them work more efficiently.

Did "some economists" really suggest that the pandemic might spark long-term productivity increases? Color me skeptical.

(UPDATE: A reliable source tells me that, yes, there really were economists making this argument back in 2020. OK then.)

Nor have I ever really believed that remote work increased worker efficiency. In fact, I'm not sure the kind of stuff the typical remote worker does even affects the productivity stats much.

But most of all, there's this:

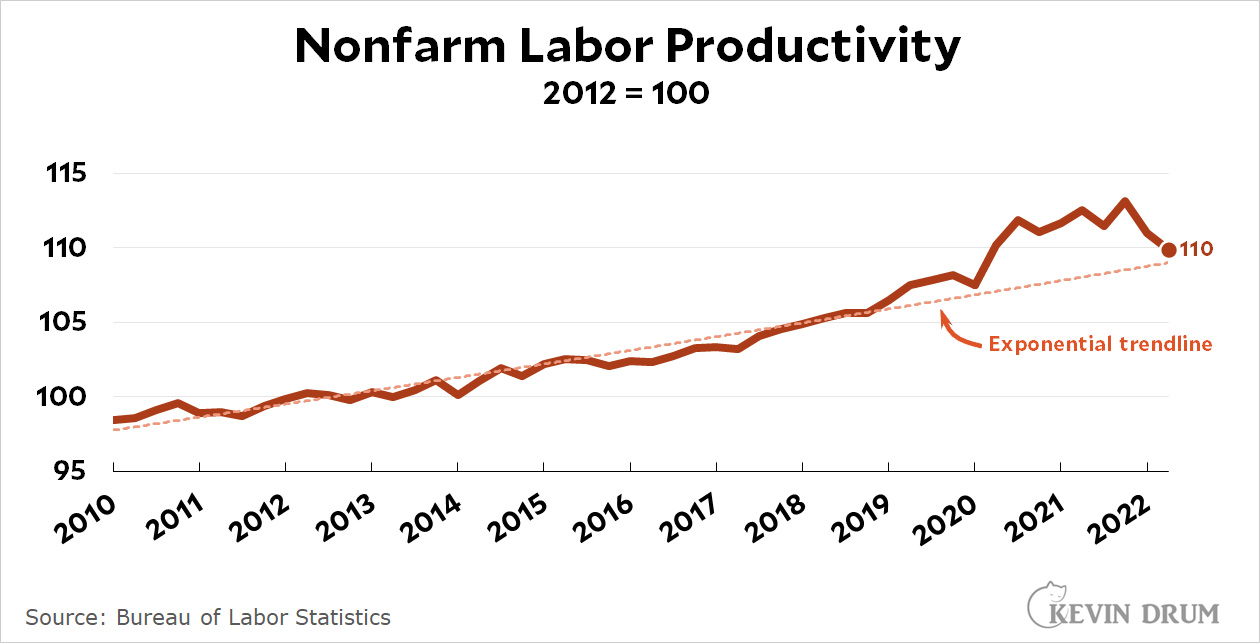

The pandemic was a singular event for the national economy, which makes it difficult to evaluate by normal historical standards. This is why I believe that a necessary first step for nearly any analysis of recent economic data is to look at the pre-pandemic trendline and see how we're now doing in comparison. In this case you see something typical: a big increase in 2020/21 and then a reversion to trend later on. In other words, the increase in productivity was a bit of chimera, probably because lots of people were furloughed and that caused an artificial productivity increase that went away when worker levels returned to normal.

The pandemic was a singular event for the national economy, which makes it difficult to evaluate by normal historical standards. This is why I believe that a necessary first step for nearly any analysis of recent economic data is to look at the pre-pandemic trendline and see how we're now doing in comparison. In this case you see something typical: a big increase in 2020/21 and then a reversion to trend later on. In other words, the increase in productivity was a bit of chimera, probably because lots of people were furloughed and that caused an artificial productivity increase that went away when worker levels returned to normal.

For now, this is just a guess on my part. But unless productivity keeps on dropping, I'm not sure there's really anything worrisome going on here.

Back to linear trend lines it seems…

"worker productivity" is complicated but the main thing that it measures is investment in labor-saving machinery. How hard people work has very little to do with it.

Of course many aspects of production related to hours were disrupted in the pandemic, as masses were laid off and many worked from home, and there were various obstacles to production not related to workers. The idea that someone at the Washington Post would have this complicated subject figure out is ludicrous.

NO.....It's the Quiet Quitting!!!!

Get with the program man....

/s

There's actually a good argument for that. Quiet quitting involves focusing on one's current job, just doing the work and doing it well enough so as not to get fired. If one has ambitions, hope for raises or a promotion, one has to spend valuable work time sucking up to the boss, ingratiating oneself with other employees, showing that one is into the team culture, bloviating at meetings, performing face time and other tasks that managers notice and confuse with productivity.

Quiet quitting means giving up all that pseudo-work and just doing one's job.

The pandemic also cut the intensity of the commute. Recovering from commuting to work and bracing oneself for the commute home can waste an hour or more a day. The commute was gone for WFH employees, and there was less traffic on the road and fewer people on mass transit for those non-WFH. Recovery was milder or unnecessary, maybe a quick cup of coffee and it was down to the job. Similarly, there was no need to gird oneself for the ordeal at the end of the shift.

I know this has nothing to do with productivity, but if you look at real GDP per hours worked, it had flat-lined after the last recession. With the pandemic, it seems to have recovered is upward trend.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=Vt4w (Real GDP/Hour Worked, guaranteed 100% to have nothing to do with productivity.)

I've been skeptical about how valuable an indicator the productivity number really is for probably 20 years, prompted mostly by Brad Delong's reliance on it as almost an autonomous variable.

I think skeptonomist is right that it mainly reflects capital investment, and that it's also affected by overall and sector-specific pricing environments, trends in hiring/overtime and management practices, and really anything that would affect the values that go into calculating it. Since they're gross-level aggregates, the numbers this deceptively simple calculation is based on encompass very complex sets of processes, very few of which conform to the common and intuitive image of a brawny worker fashioning tangible objects for market sale.

Given the real-world complexity hidden by all that aggregation, it may well be that short-term fluctuations over less than several years aren't very meaningful, and also that longer-term changes aren't always going to be easy to explain.

Good comment.

Well stated.

You mean 'productivity' is a variable 'inflation' is a variable, i.e. not a primitve measure at all? Whoda thunk.

I was more "productive" as a remote worker for a large urban institution during the pandemic, in terms of output per day. Probably 15 min less time prepping in the morning and putting on my ape suit. Saved 80-90 minutes commuting. I took less time for lunch because the cafeteria was 20 ft away from my office. For whatever reason, there were blessedly many fewer meetings, and they tended to be shorter. Easier to filter out the time wasters, and there was an esprit de corp with those who were trying to get shit done, ergo, efficient use of time. I was vastly less stressed, ate healthier, and got into a routine of regular outdoor exercise. Then, I retired. Bye the way, I loved the younger folks I worked with. Many were lovely people with a great spirit of team work.

Correlation is not causation, but did anyone notice that productivity jumped when big companies shifted to Work From Home, and started dropping when they started to insist that employees return to the office?

Investment in aids to production = productivity,`. Stock buybacks not so much. CEO pay not so much. Dividends to stockholders not so much.

Given that I have no idea of what's being measured as "productivity", it sure seems that it's getting back onto the straightline rate increase that prevailed pre-pandemic. Were employers expecting it to just keep shooting up at insane rates, because they were forcing a much smaller workforce to do all the same things as before?

And, coincidentally, making their profts shoot up similarly? Unemcumbered by higher wages to compensate the few remaining workers?

The answer is contained right in the article:

at understaffed companies the output of remaining workers rose as they picked up the work previously done by their former colleagues.

Since people are definitely not machines and they burn out over time, the rise was never a sustainable one.

The most important thing about productivity is that most of it has been going to upper incomes for the last 50 years. In this diagram

https://skeptometrics.org/BLS_B8_Min_Pov.png

the green line, GDP/capita is one measure of productivity - the overall productivity of the economy. There are all kinds of diagrams which show this inequality of distribution of production and in all of them it is obvious that wage-earners have been left behind - there has been essentially no increase in real wages over the last 50 years.

Why is it important to increase productivity if the increases only go to the rich? Suppose productivity were decreased by 20% but real wages actually went up by 20%. That would pull a lot of people above poverty. The people who have gotten the most of the productivity increases, that is the 1%, are already so well off their material needs are satisfied. This increase in the wealth at the top has certainly not increased overall economic performance. There is an excess of capital, but there is not enough aggregate demand to call for major investment. And again, in the long run it is investment which increases productivity.

Before the 70's wages were keeping up with productivity - this was in all US history, not just in the post-WWII period.

Exactly. This worker could not care less about "productivity" because I won't see any benefits from it.

Nobody seems to remember that the ‘baby boom’ was followed by the ‘baby bust’ so that as boomers retire there are fewer productive workers available to take their place. Thus productivity HAS to decline simply because of demographics.

That makes a lot of sense. There has been a definite generational transition as baby boomers retire and make way for the next generation. I'm a boomer, and I know people who retired when COVID hit rather than working a few more years. I've also seen this at a number of workplaces. For example, the Washington State Ferries had serious staffing issues as their boomer staffers retired and there was no cohort of younger workers to replace them.

All the skilled trades are having this same problem. Older plumbers, carpenters, electricians, etc. are retiring and there isn't enough new blood to replace.

Actually, no, the productivity-growth numbers as reported are calculated as the total dollars of output divided by total hours worked (for the US, that is, see https://www.bls.gov/productivity/ Of course, the local currency unit is used for other countries). Demographic changes, as well as changes in the work week or work year, and LFPR will affect the total output, but will also be reflected in total hours worked. If the labor content of a unit of output remains the same, the ratio of output to labor time remains unchanged also.

Skeptonomist and Altoid are correct that capital investment is the main driver of productivity growth; by way of technology development that restructures production systems. For a particular facility, therefore, one would generally see stepwise increases in productivity, followed by an upward trend as workers and management adapt to and tweak new technology. The basic measurement is units of output per hour of labor; output units could be widgets or restaurant meals served or help-line inquiries resolved. Some output measurements are noisier than others, but at least they reflect system efficiency.

Fine for a particular facility, but how can one measure productivity in the aggregate? You can’t add automobiles to laptops to restaurant meals to insurance claims. Economists chose to aggregate by replacing units of output with the monetary value of those outputs. But, as Altoid notes, lots of factors affect the economic value attached to goods and services, from supply shortfalls to interest rates to fashion. The labor-hour content between generic sneakers and shoes bearing the (machine-printed) signature of a basketball superstar varies far less than the price. Measuring productivity in terms of value doesn’t just introduce more noise (which is random and averages out over larger data sets), it contaminates the measure with nonrandom, spurious effects having nothing to do with efficiency of production.

And among those non-random effects in many sectors, I'd suggest pricing power of individual firms and/or oligopolistic pricing has reached the point of having effects significant enough to show up in productivity numbers. Of course that power would point to "rising productivity." But so could the kind of covid-period price distortions we might remember, along with all the furloughing and other labor adjustments.

So if you think Kevin's graphing here is up to his usual standards, which I do, he's right-- what we're seeing really looks like a reversion to trend that really shouldn't be alarming to anyone who isn't looking for a headline or an excuse to bash the rank and file.

People should really read the comments in WaPo for that article. To sum up nearly every comment - of course productivity is down because employers suck. The realities of 40 years of the C level treating employees like numbers on a spread sheet is the most under reported story in the media, and the a major driver of all the vitriol we see in society today.

Every time I see these recent stories about the rail unions rejecting contract offers because they don't include paid sick leave, I ask myself how many of the suits in those railroad C suites would be willing to accept a job that didn't have paid sick leave or its equivalent. I don't guess there would be many.

This is a trend line I can believe in. 2020 and 2021 clearly were unusual times.

If there are sharp changes in the composition of the labor market, "productivity" changes aren't necessarily what most people think of.

"Productivity is calculated by dividing an index of real output [such as GDP] by an index of hours worked by all persons, including employees, proprietors, and unpaid family workers." - BLS

So, if for example, there are mass layoffs of lower-paid workers (say, retail hospitality), then productivity of the REMAINING workforce goes up, because less "productive" employees (measured in value produced) aren't counted.

And the converse is true when lots of lower-paid workers are hired (back) - the AVERAGE productivity per worker drops, because the numerator is based on value-added, and a rough proxy for that is wages. [Average wages have decreased.]

> I'm not sure the kind of stuff the typical remote worker does even affects the productivity stats much

Um, you mean like teaching computers how to automate different tasks doesn't affect productivity?