A recent podcast from the Niskanen Center focuses on whether political elites have a good sense of what the public believes. Short answer: not really. Alex Furnas, a professor at Northwestern's business school, summarizes his research this way:

We found that for policies that elites themselves strongly favored, they overestimated public support by about 12 percentage points. And for policies that they themselves strongly opposed, they underestimated public support by about 12 percentage points. So there’s sort of a 20 to 25 percentage point difference in elite evaluations of public support for policy, depending on whether the individual elite strongly supports or strongly opposes that policy.

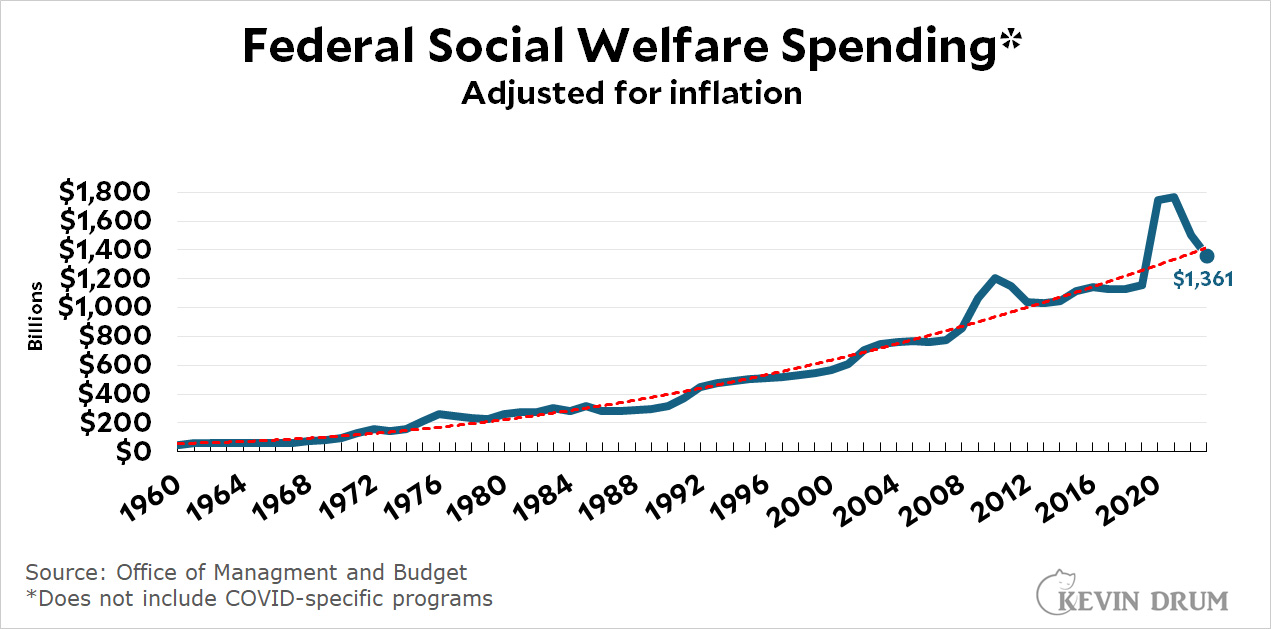

Here's the chart:

Basically, liberals think the public is more liberal than it is, and conservatives think the public is more conservative than it is. But there are exceptions:

Basically, liberals think the public is more liberal than it is, and conservatives think the public is more conservative than it is. But there are exceptions:

- The public favors a wealth tax even more than liberals do.

- The public dislikes a path to citizenship even more than conservatives do.

- The public hates carbon taxes.

- But they love low-income clean energy.

Elsewhere in the podcast, Adam Thal, a political science professor at Loyola Marymount, talks about elite perceptions of poor people:

Why do politicians sort of ignore problems facing low income people in the United States?... There’s good reason to think that because they don’t experience a lot of economic problems themselves, they might underestimate the scale of those problems, not really understand how bad things are for low income families.

....I did not find that to be the case.... [But] there’s definite polarization. Democrats in particular tend to really overestimate the scale of these economic problems. Republicans are less likely to overestimate them and in some conditions underestimate them.

It turns out that political elites know perfectly well how tough things are for poor people. In fact, Democrats overplay this significantly. As for Republicans, they have a pretty accurate sense of things but just don't feel like doing anything about it. Their lack of concern has nothing to do with misperceptions. It's deliberate.