The Washington Post has yet another story today about the calamitous shortage of US public school teachers in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. It starts off with the headaches faced by Carolyn Stewart, the superintendent of the Bullhead City School District in Arizona:

The 2,300 students in her district had been back in school for several weeks, but she was still missing almost 30 percent of her classroom staff. Each day involved a high-wire act of emergency substitutes and reconfigured classrooms as the fallout continued to arrive in her email. Another teacher had just written to give her two-week notice, citing “chronic exhaustion.”

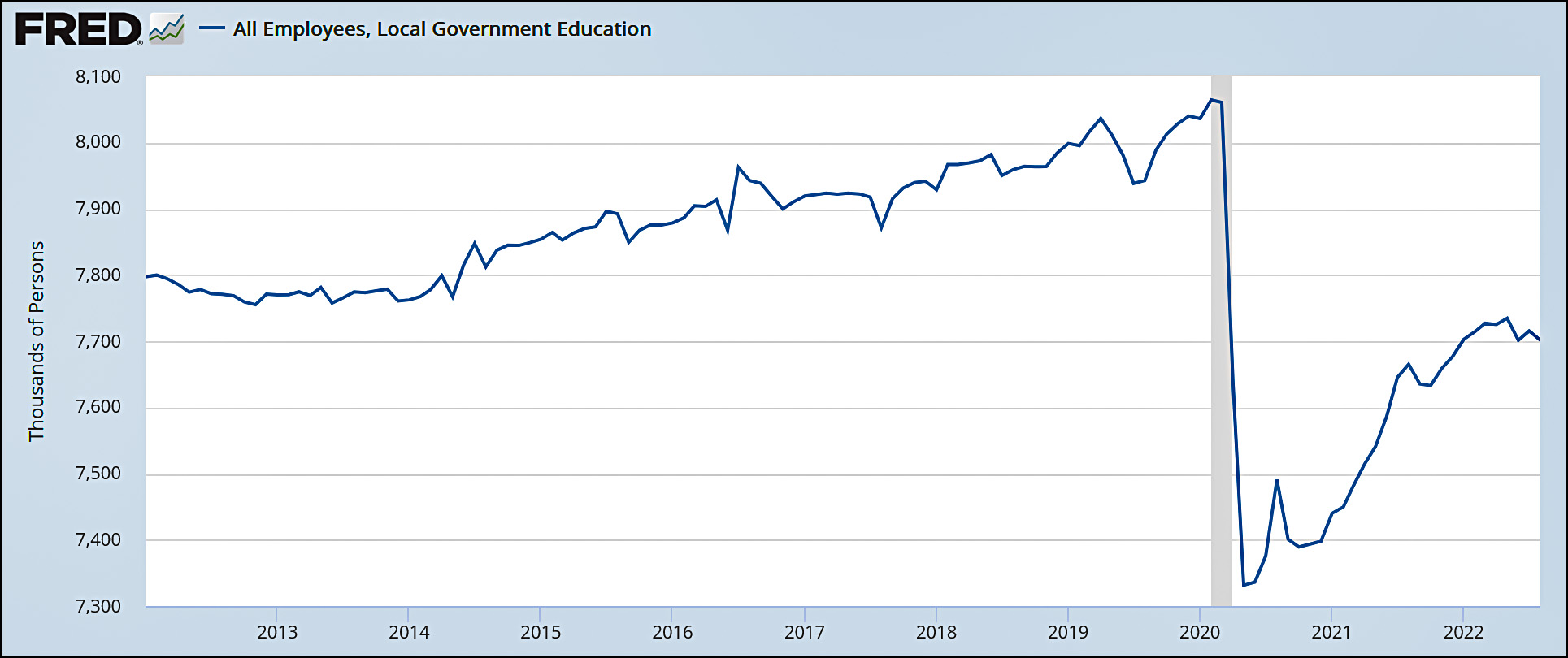

....Stewart had been working in some of the country’s most challenging public schools for 52 years, but only in recent months had she begun to worry that the entire system of American education was at risk of failing. The United States had lost 370,000 teachers since the beginning of the pandemic, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Maine had started recruiting summer camp counselors into classrooms, Florida was relying on military veterans with no prior teaching experience, and Arizona had dropped its college-degree requirement.

Just to start off, I don't doubt for a second that Stewart is having trouble hiring teachers in her high-poverty school district out in the middle of the Mojave Desert. I wouldn't be surprised if they have hiring problems every single year. But Bullhead City is just one school district, so let's check the national statistics quoted in the story:

Spot on! The current number (for August 2022) is 370,000 less than the number for January 2020.

Spot on! The current number (for August 2022) is 370,000 less than the number for January 2020.

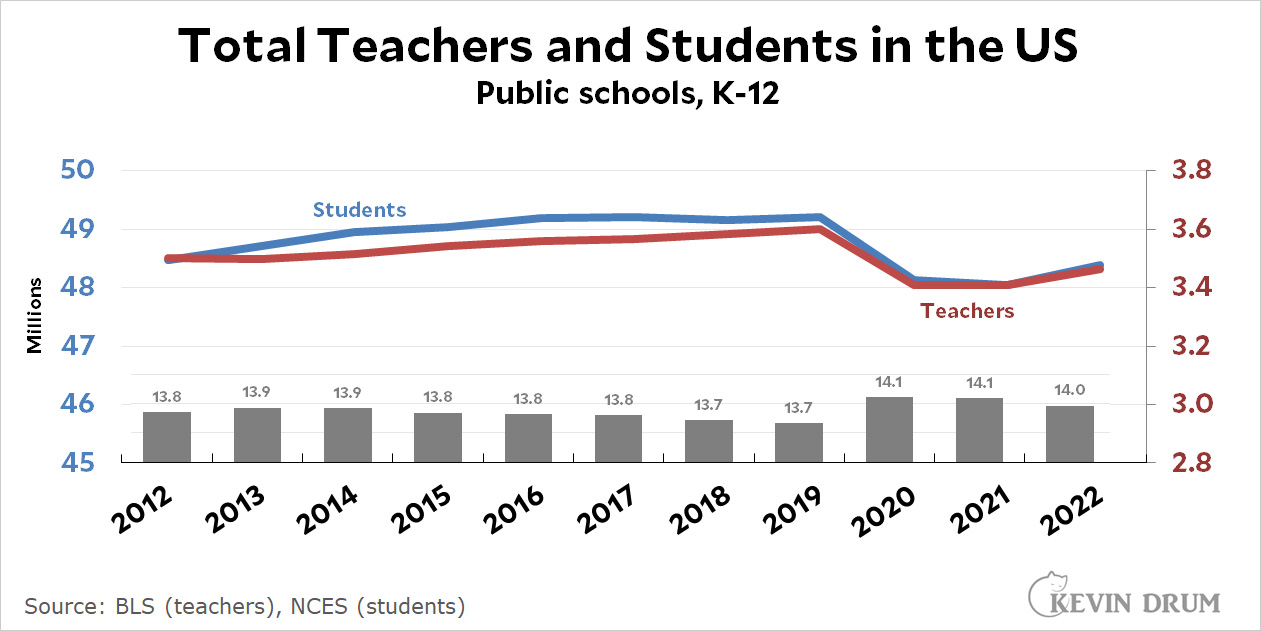

But there's a problem here: this number is for all education employees, fewer than half of whom are classroom teachers. The actual shortfall is closer to 160,000. And there's more: you really need to compare this to the number of K-12 students over the same period. Here it is:

The number of teachers is lower than it was before the pandemic, but so is the number of students. In other words, while there might really be a shortage of teachers, you have to account for the decline in the number of students to put a real number on it. And that's pretty easy. The teacher-student ratio (the gray bars) is currently 14:1 compared to 13.7:1 in 2019. A bit of simple arithmetic tells us that in order to get back to the teacher-student ratio we had before the pandemic we'd need about 70,000 more teachers.

The number of teachers is lower than it was before the pandemic, but so is the number of students. In other words, while there might really be a shortage of teachers, you have to account for the decline in the number of students to put a real number on it. And that's pretty easy. The teacher-student ratio (the gray bars) is currently 14:1 compared to 13.7:1 in 2019. A bit of simple arithmetic tells us that in order to get back to the teacher-student ratio we had before the pandemic we'd need about 70,000 more teachers.

So the real shortage is less than a quarter of the raw number quoted in the story. If Arizona is similar to the rest of the country, it's probably short about 1,500 teachers, or less than one per school.¹

If you cherry pick, you can find plenty of schools—or entire districts—that are well above that average. Bullhead City sounds like one of them. But overall, the United States K-12 system is not at risk of failing.

Not from raw numbers of teachers, anyway. If you want to make the case that the problem is dire for some other reason—for example, schools trying to handle both remote and in-person teaching until they're fully in-person again—that's fine. Make your case. But let's at least get our sums right when we do it.

¹The United States as a whole has about 95,000 public K-12 schools. If we're short 70,000 teachers, that's an average of 0.74 teachers per school.

Start paying teachers a decent salary and there will soon be a surplus. This country simply does not value educators, at any level.

This country simply does not value educators, at any level.

That seems a far-fetched statement. The US spends about an average share of GDP on education. Higher than Germany or Ireland or the UK, for example:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_spending_on_education_(%25_of_GDP)

These figures probably underplay US education spending, mind you, as they exclude private sector monies spent on schooling (and the US has a large private sector education component).

The amount spent on education is not the same as what teachers earn.

In Arizona, they start at about $30k. Full-time.

Teacher salaries aren't much better even in countries with much stronger, federalized education systems.

This article is a few years old, but it gives you an idea: https://www.theguardian.com/teacher-network/teacher-blog/2014/sep/05/how-the-job-of-a-teacher-compares-around-the-world

Those other countries to which you're referring also have national health care systems and other welfare systems that provide things that American teachers are expected to pay for themselves. Plus I'm pretty sure that teachers in those countries don't have to provide supplies out-of-pocket (and no, that's not an urban legend).

I'm a public school teacher and you're fairly off base here. There's just not consistency between the data you use, my experience, and other ancillary data.

1. You only account for warm bodies, not qualifications of said teachers.

2. These numbers fundamentally don't make sense. Where did 2 million children go? The net migration rate doesn't support that.

3. Unfortunately there are quite a few administrative positions now in place. Lead teachers, AG coordinators, EC coordinators, data managers, etc. I don't see the data disaggregated by teachers vs. educational employees.

4. Teacher pay is declining in accord with inflation. Why on earth wouldn't that cause people to leave the profession, or more immediately, cease to enter the profession?

5. Enrollment in teacher preparation programs have dropped like a stone. So the potential qualified candidates have dropped by 1/3rd before the pandemic, and reportedly kept dropping. How does this not show in data?

6. Decreasing class sizes would probably show up in increasing per pupil spending. In NY per pupil spending is down from $28k in 2018 to $24k in 2022. NC per pupil spending also seems to have decreased a similar amount.

Also, my very limited experience just isn't matched by this:

1. We have no subs. I cover for missing teachers 4x a week now. I did that twice by choice in the 5 years preceding Covid.

2. It takes a long, long time to replace teachers now. It took 3 hires and a year and a half to replace me when I left my old job.

3. We're hiring tutors to help replace missing math teachers.

4. My personal class size has been increasing. It has gone up 15% this year.

You've had this take a couple times and I've been too late to comment, but I really think you need to dig deeper. There's just not the consilience I would suspect from all the ancillary data.

Usually I enjoy Kevin's data dives, but this one seems wrong headed. As others have pointed to, this is a problem shaped far more by state and local factors rather than national ones. To say that we're short "an average of 0.74 teachers per school" nationally assumes a level of commonality that simply doesn't exist.

Setting aside pay disparities between states, consider the problem from a cultural standpoint. Over the past few decades we've established a trend in our country where Americans with college educations are increasingly concentrating regionally. Teachers would hardly be exempt from this, which is undoubtedly exacerbating shortages in rural and exurban areas like Bullhead City. As tigersharktoo pointed out, we're told that in a capitalist society the solution to this problem is to increase salaries, only rural/exurban regions don't have the tax base do to that easily, nor is there much incentive to do so. After all, with educators increasingly being demonized as brainwashers for woke socialism, why would anyone in a community that went for Trump by 41 percentage points want to pay even more in taxes to bring them into their community?

The missing children still exist, but they're being educated through either private schooling or homeschool.

Parents haven't forgotten how they were stuck with this job during the pandemic. Many of them adapted, getting their children into private school for in-person learning after seeing how remote learning was not working for them. Others took a more personal role in the process and discovered they loved it. Add to this all the roadbumps involved in returning to public school (strikes, etc). They might return, but it will take awhile.

Also, this isn't 2 million students. According to the graph, total students peaked at 49.3 million, then dropped to 48 million, then rose to 48.5 million. This leaves a difference of 800 thousand - a loss of only 1.6%. Just from looking at the numbers on the charts, it looks like the teacher loss is about the same percentage.

Remember that the bottom of the chart is NOT ZERO. Confining the chart's vertical range like this makes the changes in data stand out more, but it loses its overall context. Overall, these numbers show the sky is not falling.

And, everybody's wages are falling when inflation is factored in. While I agree that teachers aren't paid enough to begin with (imo, too many administrators, etc, taking money away from those who are working on the "front lines"), this particular problem is not endemic to teachers.

And keep in mind that your personal experience doesn't reflect the overall data. Claiming this is like claiming global climate change doesn't exist because it's not getting any warmer right where you live.

An issue with comparing number of students to number of teachers is that it presupposes that we already had an appropriate number of teachers for the number of students.

We did not, and it was a burgeoning problem - the start of that students/teachers graph actually makes that apparent, as the growth in the number of students outpaced the growth in the number of teachers, and that's not a trend that started at the beginning date of that graph. Class sizes have been getting out of control for decades, and we've been short teachers for just as long (or even longer, if you think class sizes ought to be pretty small).

I know that schools in my locale are struggling to keep slots filled. Many are filled with interns still getting their credentials or retired teachers doing the district a favor. I'd be curious to know if there's been a significant difference in those types of hires or if it's just anecdotal. I'd assume this problem is intensely regional, so I could see it going either way, but it reminded me of this:

https://www.ksby.com/arizona-teachers-no-longer-need-college-degree

Again, Kevin is using aggregate numbers to conclude no shortage of employees exists without looking at the distribution of those numbers. If the 160,000 teachers vanished disproportionately from urban and rural districts while the 1,000,000 or so students vanished disproportionately from suburban districts (where I’d guess a parent is much more likely to be able to homeschool the kids… or did 1m kids just emigrate/die during the pandemic?!), there still would be a geographic mismatch between teachers and students. Teachers can’t just be instantaneously shifted from suburban Rust Belt districts where they possibly aren’t needed anymore to urban or rural Sunbelt districts where they are in shortage. There is no federal agency nor any agency in any state that forcibly reassigns teachers from districts experiencing underenrollment to districts experiencing overcrowding. *Eventually* relocation bonuses and higher wages will attract some teachers to areas with shortages and consolidating schools and enacting layoffs will repel some teachers from areas with surpluses…. But “eventually” is going to take years to come to fruition. In the meantime, being unionized will lock millions of teachers into a lot of districts even if they aren’t needed there.

TL;DR:

Kevin’s entire argument reminds me of how centrally planned economies used to do things like calculate exactly how much grain their entire country needed, then dutifully make sure that target was achieved, and then the leaders and bureaucrats refused to believe that anyone in the country could be starving because the grain wasn’t actually distributed evenly across the whole population. (North Korea functioned like this during their “Arduous March” in the 1990s.)

Kevin concludes that we have enough education resources to meet our education needs… and is totally blind to how allocation of those resources may not be at all related to needs.

Good analysis, Austin.

Kevin tends to take a rather simplistic view of issues like this. Economic problems tend to be about distribution. During the notorious potato famine, Ireland was producing more than enough food to feed everyone in the country, but food was being exported and around a million people died of starvation and related problems. How many battles have been lost because the right division was in the wrong place or a horseshoe was missing a nail?

Agreed. Kevin also seems to approach all these problems as if there is some central planning agency that (1) exists and (2) has the power to coordinate and reallocate resources. In reality, (1) there is no national or even statewide mechanism for forcing schools with too many resources (such as teachers, but also buildings, school buses, books, etc.) to share them with other schools experiencing shortages of those resources and (2) all school districts are acting independently to fix whatever problems they identify - whether that be “warm bodies to watch currently teacherless classrooms” or “a desire to lower class sizes even further to let our kids get ahead” - which means that it’s entirely possible the richer districts are able to bid up salaries and keep the poorer districts from fixing any problems that emerged during the pandemic.

If only I could meet Kevin, I’d tell him face to face that it’s obvious this country - one of the richest countries to have ever existed - has enough resources to fix pretty much any problem, even now post pandemic. The dilemma is (and always has been) that those resources aren’t allocated in relation to need, so the problems persist.

I have zero doubts we have enough teachers nationwide to teach all our kids. But all of US history demonstrates confirms my serious doubts that we will ever allocate those teachers equitably across all schools. Some schools will always have way more teachers than they need, leaving other schools will way fewer teachers than they need.

I have no idea why Kevin cannot see this, just like he can’t see that some places will have far more jobseekers than they have jobs and other places will have the reverse… and that’s a real problem cause most people actually want to stay where they are and not reallocate themselves to make the numbers work out like the wonks say they should.

Even if Kevin is right about the number of students, schools are probably not going to reduce the number of classes and redistribute teachers on the assumption that students won't be coming back soon - what if they come back during the semester? But I don't know - what other events like the pandemic have there been in the experience of school administrators?

US population: 330M, pretty flat since pre pandemic

US GDP: 21T, down about .5T from pre pandemic

GDP per capita: $63,600 or so

Kevin: “It’s hard to see how anybody could be experiencing poverty post pandemic, when it’s clear that the US has enough GDP to allow everyone to have enough to live a middle class existence.”

Maybe Arizona should pay teachers more. Supply, demand, capitalism

and all that.

Now why do that when you can just eliminate the requirement for teachers to have a college degree? Really, any warm body will do when all you really want is a glorified babysitter rather than someone who actually knows something about their subject and is capable of educating their students about it.

All we really need is for the kids to recite the Pledge of Allegiance and learn to worship the Founding Fathers. Anything beyond that is liberal propaganda and grooming.

Yeah, who needs math, anyway?

'Algebra' is Sharia Math! It says so right in the name!

& trigonometry implies three genders exist.

My husband just retired as a teacher. He loved the students and most of his co-workers, but even in a school with a responsive administration, teachers get the short end of the stick. The pay is relatively low for the education and experience required. Politicians find teachers to be convenient scapegoats for every social problem in America, and they are constantly under attack by the news media.

In short, teachers are not treated like respected professionals. They are treated like trash. And it is up to the schools to provide so much of what America fails to provide especially to poor children--social support, protection from violence (don't get me started on resistance to gun laws despite rampant school shootings), even food for the hungry, clothes for those lacking adequate winter coats...and psychological support.

America is a very cruel country, and teachers--and the entire public school system--bear the brunt. And always underfunded, especially in poorer districts.

To any young person interested in teaching, I'd recommend they do anything else.

I have to agree with you, reluctantly, that large swaths of the country do indeed seem to be cruel and getting crueler.

My mother was a teacher in NYC in the 1960s and 1970s. She was a member of the teachers' union, the UFT. I remember her saying that there had been a big debate about whether teachers should join a union or a professional society like doctors. They were all college educated and thought of themselves as professionals, but, in the end, they knew that they were workers, so they went for a union. My mother said that, in retrospect, that had been the right decision.

The drop in respect accorded teachers by society is a fairly new phenomenon. But it's not much of a drop -- teachers are still respected more than doctors and almost as much as members of the military. Which is to say that teaching will get you quite a bit of respect. I enjoy the status boost from my job! The people I meet who don't respect teachers seem to be people for whom schooling was a waste of time -- and they say so.

Now do nursing.

You are ignoring real life.

One district wants 20 kids per teacher and they had 50 teachers for 1,000 students. The number of kids drops to 980. So they could layoff a teacher and keep the magic number of 20 students per teacher. (I just made up the 20 number, use any number you want, it doesn't change the results.)

To keep the nationwide ratio constant, that means that another school has to be one teacher short. Random variations will mean that many districts are overstaffed and many are understaffed. Smaller schools where the number of 4th graders in the school drops from 18 to 13 means you have one teacher with a far smaller than average class or combine two grades together.

Now, remember that we haven't been close to the "proper" number for student teacher ratio for years and you will have many, many districts that are desperate for teachers.

Finally, you have states like Florida which don't spend much on students and have low salaries. Why would a teacher stay?

All schools are local.

The other issue is that the lack of support staff can make teaching that much harder. It also means deferred maintenance, so the experience in the school can be....challenging. Not to mention, schools have had to divert money to security and spend time doing active shooter drills. Plus they need more IT staff, not just to maintain their PC's, but to monitor social media, manage remote classes, etc.

In my suburban NY district, I've heard the real problem isn't with teachers per se, but with substitutes. They were mostly older, retired people looking for a little side income a few days a week, but with Covid, most of them stopped doing sub work in schools. Too risky.

Anecdotal...but this exactly the problem in my area of Colorado. No substitutes, many fewer teaching assistants and school support staff....small reduction in teachers. Add all these pieces up and the schools are struggling.

One little thing to note: when kids leave public schools as happened during the pandemic, the SPED kids are the least likely to go. There just aren't enough SPED services in charters or private schools for many of them to make the switch.

As public school enrollment drops, the percentage of the student body that needs extra services rises. There was already a shortage of SPED teachers and aids, and that has only worsened since the pandemic.

What happened to the students? Did they drop out? Is there a data glitch?

The unspoken assumption is they dropped out of the public schools. Either they went into private schools or they are now being homeschooled. (Of course, some tiny percentage also died of Covid, but since that conflicts with the “Covid is only dangerous to the elderly (who are expendable)” framing that our media have settled on since vaccines became a thing, we’ll ignore those unfortunate tykes too.)

Since generally it’s only the upper middle class and wealthy that can afford nowadays to have a parent (mom) stay home to home school or pay tuition at a private school, I’d venture a guess that the districts experiencing the biggest drops in students may not be the same districts as those experiencing the biggest drops in teachers. Especially since wealthy and upper middle class parents tend to cluster in school districts with high teacher salaries that are lucrative enough to retain teachers even during the bad times like, say, the last 2.5 years have been.

But Kevin just ignores this possibility and presumed instead that there is somebody out there that is coordinating both teacher departures and student departures from schools, and adjusting staffing levels to keep all schools at about a 13-14 student per teacher ratio.

Doesn’t matter whether it conflicts with a narrative. As of 9/28/22 the CDC puts the number of children who died of/with COVID-19 at … 925. That is epsilon.

Nit: that would be school-age children. Ages five to eighteen.

Hate to break it to you, but high proportion of Chicago kids are -- drumroll please -- privately educated. And have been for a long time. I speak, of course of the Catholic schools, but they're not the only ones.

There was a big shortage here in Arizona before the pandemic. They were letting anyone teach, certificate or no.

How were the under-credentialed doing?

I'm guessing not very well, considering that they dropped the requirement for a college degree after that.

Our feet are in the oven and our heads in the freezer but on average we are quite comfortable…

I lived in the Bullhead City area briefly, about 30 years ago. It is most definitely not a community with a lot of resources; mostly it was retirees aspiring to a middle class existence and workers at the Laughlin casinos across the Colorado River. Back then the schools were woefully underfunded (that money was better spent on quarter slots at the Riverside) and generally were treated as an afterthought. I can't imagine it has improved much since we moved away.

The average might be mostly where it should be, but "average" means approx half the districts are overstaffed and half are understaffed. As far as those school districts that are understaffed and underfunded, there is a culprit: the elected officials, and ultimately, the voters.

The elected officials are balancing taxation versus school funding (among other things). Many officials have learned to not increase taxation (which, in my state, shows up as part of my property tax) lest they be voted out for someone who will obey the will of the voter. These voters are thus ultimately responsible for the lack of school funding - they just don't place proper value on that service and would rather keep their money.

The districts that are overfunded see the opposite - the voters like that service and are more willing to pay the increased taxes to have it.

So what we're seeing on this "micro" economic scale is local community values at work.

My advice for parents who are concerned about quality education in the public school system would thus be, GTFO of that area in favor of better. Seriously, every parent should be asking "what sort of education will my kids get here - and what sort of future will my kids have as a result?" And yes I know, the solutions aren't easy; welcome to Earth. I sacrificed so much to ensure my child would have a good education, lamenting constantly about how this system was of no help, but I did it anyway and would do so again.

My advice for teachers follows the same lines; some communities do not prioritize the children, and thus do not prioritize you. There's nothing you can do about it; move to some place better.

Yes, if only everybody just moved to good school districts, everybody's children would get good educations. Thanks for the tautological advice.

Of course, if everyone already in good school districts erects barriers to entry, it becomes a lot more difficult to GTFO of bad school districts. (No amount of "prioritizing their children" was going to get black parent's kids into white neighborhoods' schools in most states prior to the 1960s.)

Also, you are aware that not all tax bases are created equal, right? That there are school districts that just happen to have the huge shopping mall or the region's biggest employer or miles of beautiful coastline and thus manage to generate more cash than they know what to do with from just 1 penny of tax on property, while other school districts have tax rates 10-20x their neighbors and still struggle to raise enough funds to keep teachers' salaries competitive. It takes a lot of gall to accuse the latter school districts of not placing "proper value on that service." You can't get blood out of a stone, and poor school districts can't get revenue out of abandoned properties.

Shorter diatribe: Fck you and fck your "I've got mine" entitled view of the world.

Plenty to discuss relating to the application of education across the county and these data points are useful to get a feel for the educational environment.

Any real discussion means having, at a minimum, 50 different discussions on the issues and concerns. These are State/Local based issues in the most important areas....funding, management, and fields of study. And all have to meet the needs of their particular area.

Sooooo . . . where did all the students go? I know they didn't go to private schools. Is K-12 no longer mandatory?

Many stayed online learning. Many districts have expanded online learning options or offer hybrid learning. Florida is the 3rd largest state and it has been investing with online virtual high school which expanded during covid

I’m always careful to separate anecdotal data from long term data over time which you is why I like your blog and all the charts. This former math teacher approves. I quit teaching during the pandemic after 15 years of grueling, thankless, under appreciated work. That being said I think that we can’t underestimate the overall moral of teachers and how this discourages college students from entering education programs. The teacher shortage may not be as acute as some reports suggest but schools are increasing class sizes to deal with teacher shortages.The other issue is that the average experience level of teachers has dropped significantly in the last two decades. This results in more inexperienced teachers in front of students. Experience does not always equal competence and I have worked with some fantastic teachers with only a year or two of experience. But having mentors for new teachers is important. When the most veteran teacher at your. As chili has taught just 5 years that’s a problem.