I'm an idiot. I got into a Twitter beef about housing and now I feel like I have a point to get off my chest. It's this: there's no such thing as a shortage, full stop. There are only shortages at a particular price. Price, as it always has been, is the great mediator between supply and demand.

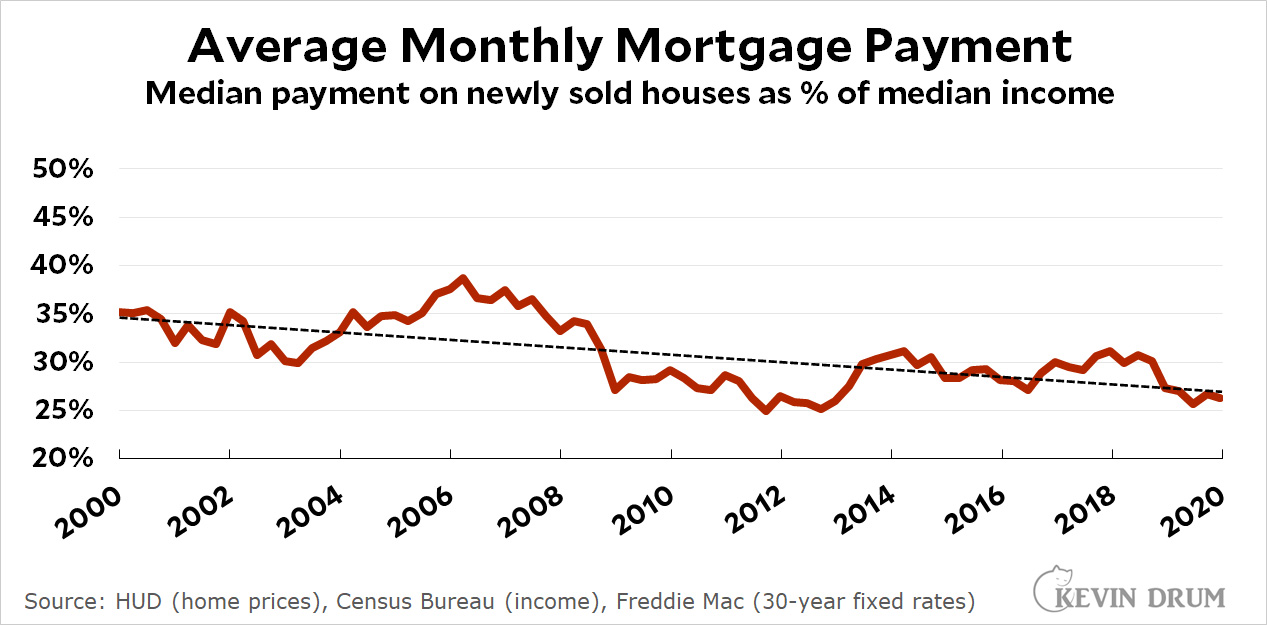

So when you say that we have a "housing shortage," all you're really saying is that you think the price of housing is too high. But aside from the past year, neither housing prices nor rents have budged more than slightly over the past couple of decades:

This hasn't stopped anyone from saying we have a housing shortage. Housing experts have been warning about it forever. But if this isn't based on rising prices, what is it based on?

This hasn't stopped anyone from saying we have a housing shortage. Housing experts have been warning about it forever. But if this isn't based on rising prices, what is it based on?

That's the crucial question: how much housing should we have? And who decides? There's no cosmic "right" number for housing stock, only comparisons over time and personal opinions based on anecdotes.

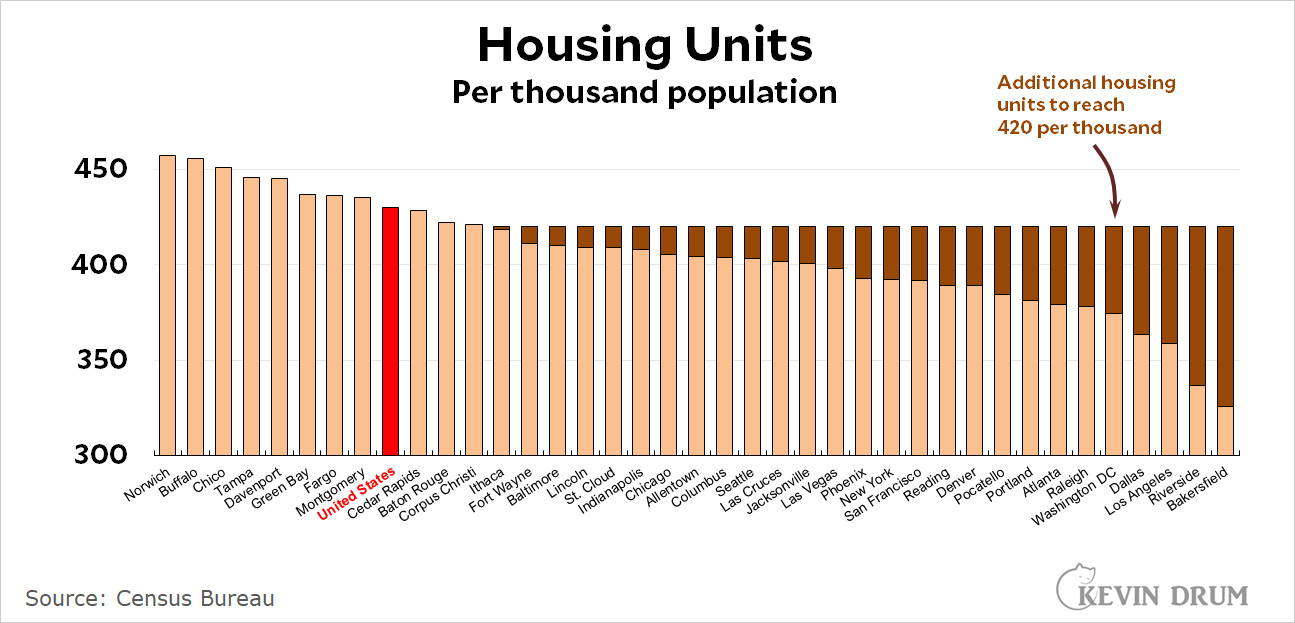

For example, here's a chart showing the level of housing stock in a random selection of cities, both large and small. The current housing stock is shown by the light orange bars:

The "additional housing" bars are based on a simple local anecdote: the belief that Los Angeles County needs to add about 800,000 housing units. If you translate that into a per-capita figure you get a goal of 420 housing units per thousand residents. If you then apply that number to all the other cities in my chart, you get the dark orange bars.

The "additional housing" bars are based on a simple local anecdote: the belief that Los Angeles County needs to add about 800,000 housing units. If you translate that into a per-capita figure you get a goal of 420 housing units per thousand residents. If you then apply that number to all the other cities in my chart, you get the dark orange bars.

Is that the level we should aim for? Why? Is there a good reason that our biggest, most crowded cities should continue growing into mega-crowded cities? Or should they slow down and let medium-size cities grow into big cities instead?

Whatever your answer, it's an opinion and little more. Some people, mostly young ones, want to move into urban cores and are unhappy that they can't afford it. Their opinion is that we should allow massive growth while somehow stabilizing demand so that prices will come down. Other people, mostly the ones who live in crowded cities already, don't want their streets and their buses and their subways to be even more jammed than they are now. They'd just as soon keep growth low.

But the law of supply and demand won't be denied. If you increase demand, as young people are doing, prices go up. If you increase supply, prices go down. If you increase both supply and demand, prices will . . . do something.

But that's not all. Nobody likes to say this, but the easiest way to increase supply is to let prices rise. Conversely, if you reduce prices, perhaps by mandating affordable housing, supply will go down.

I'm not expressing an opinion on any of this. For all I care, developers could demolish the tennis courts next to my suburban house and replace them with a 50-story high-rise. We'd probably need to widen a few streets, though.

But there's no getting around the basic facts. There is no "right" level of housing. When demand goes up, so do prices. When prices are forced down, supply goes down. Killing off zoning restrictions and letting the market loose will have unpredictable effects. My guess is that prices would stabilize for quite a while, and might then start to decline. Maybe. I don't really know and neither does anyone else.

For the most part—though not entirely—this question is unrelated to other issues like homelessness and affordable housing. By far, the biggest obstacle in the way of fixing homelessness is the fact that no one wants shelters near them. The big problem with affordable housing is figuring out who's going to pay for it. Neither has very much to do with the overall supply of housing stock.

So: what's the right level of housing stock? And who decides? If you can't answer that, you probably shouldn't have much of an opinion on the more complicated stuff.

"... It's this: there's no such thing as a shortage, full stop. There are only shortages at a particular price. .."

I suppose you can define things so this is the case but I don't think it is always the most useful way of looking at things particularly in the short run. I think for example it is reasonable to say we had (have?) a shortage in baby formula.

Exactly: If you are talking about luxury watches or yachts demand and supply will work perfectly on their own. Nobody needs those things to live or even to be happy.

But if we are talking about bread the same forces will lead to people starving to death. Housing is another essential need. And right now we have unsustainably hight rates of homelessness in many areas (including where Kevin lives) and surroundings. In such circumstances the attitude of simply falling back on "econ 101" is unbearably blasé. I call such a situation a shortage even though there is indeed no shortage of "average" level housing. I don't think there is a supply and demand solution to the homelessness problem.

It is even worse: The period in the graph is one where mortgage rates were falling. No surprise that the graph looks like it looks--on average, mind you! This is about to change. The shock might lead to "housing surplus" quite quickly, a situation where housing is unaffordable to so many people that houses stay empty. The Fed is presently busy bringing this situation about (Kevin does in fact disagree with the Fed on this one).

“For the most part—though not entirely—this question is unrelated to other issues like homelessness and affordable housing.”

What!?!?

You spent the whole piece saying that price is the “great mediator between supply and demand” and that we don’t have a housing “shortage”, we just have high housing prices.

And then you say that high housing prices are mostly unrelated to affordable housing.

I mean seriously, what!?!?

Homelessness has a lot of root causes. There is actually quite strong evidence that one of the major causes is housing unaffordability, but I’m not going to argue that point here.

But Kevin, you are literally saying that the high price of housing is mostly unrelated to affordable housing.

You’ve lost the thread, man.

He's also saying that the high price of housing somehow has nothing to do with supply and demand, while saying that the price means we don't have a shortage of supply.

It can't be both.

Just seems like Kevin is doubling and tripling and quadrupling down on his take that there is no shortage. That's what I'd call him an idiot for - not owning up to his mistaken takes, and being unwilling to acknowledge (still!) that housing is local and not national.

"And who decides? If you can't answer that, you probably shouldn't have much of an opinion on the more complicated stuff."

Uneducated opinions are now banned from K. Drums comment section. I, for one, believe this will increase GDP by 0.1% in the next quarter but it will lower inflation.

I love reading the exchanges between you and MattY (and his fellow YIMBY travelers) on Twitter. I learn a lot from the exchanges. But I myself learned very quickly to never, ever, engage with YIMBY zealots. The cycle of comments usually follows a pattern: it starts out with a lot of policy, but ultimately devolves into agita-inducing hectoring and name-calling.

That sounds like a conversation on Twitter about any topic at all.

I think there is something more than just (mostly) young people wanting to move/live in the urban core.

You need to live where you can find a job. In my experience, that is far, far, far, far easier in an urban core with millions of jobs, than in a relaxed, cheap more rural environment with a few thousand.

Maybe Denver is different than most, but it makes very little difference if you choose downtown Denver or the suburbs, it’s all expensive.

So, I think this is more than just preference towards large cities.

I think there is something more than just (mostly) young people wanting to move/live in the urban core. You need to live where you can find a job

This.

I'd love to see an analysis that compares housing costs in two broad kind of markets since, say, 1990, that make up everything in US:

1) Metro areas where either median household income and/or population have grown by at least 90% of the national average

vs.

2) Ones that have not.

You'd certainly expect the growth in housing prices in category #1 (prosperous metros) to have significantly exceeded what's happened in category #2 (stagnant areas). In other words, national averages don't tell us a lot about how much or to what extent housing affordability is impacting the lives of people, because a lot of them don't have the option of living in cheap areas, because of lack of jobs. Also, my understanding is economically deprived areas actually suffer from significant affordability issues themselves, due to low incomes.

The starkest evidence for the phenomenon I'm describing (or attempting to describe) is the fact that our highest wage areas are increasingly being outpaced in terms of population growth by lower pay regions. This wasn't always the case. I've seen pretty credible statistics suggesting that not having laws that make it illegal to build housing would alone translates into utterly enormous economic gains (like, approaching $10 trillion in additional GDP).

Maybe there's something inevitable about all this, and no society, ever, avoids the particular bullet of seeing its most productive regions slip into slow growth mode. But it sure seems like something is broken.

It very much depends on what kind of a job you're looking for. In a relaxed cheap small town environment, there may not be a large number of jobs, but there also aren't a large number of job seekers, with the result that it is often easier to find a job in a small town. Of course, if the job you're looking for is as a junior executive in a Fortune 500 company, you probably need to be in a big city. If the job you're looking for is clerk in a grocery store, you can do just as well or better in a small town.

Nobody likes to say this, but the easiest way to increase supply is to let prices rise.

I'm sure I'm missing something obvious, but the above seems off.

If prices are rising over the long term, it surely means supply is being held down, right?

So, "letting prices rise" isn't what increases supply. What increases supply is allowing companies that build housing to, um, build housing (as much as the market can absorb). And we currently make that illegal in a lot of places.

Well, were prices to rise “enough” then more housing would, presumably, be built where it is already allowed.

Still, over the long term certainly housing, like anything else, cannot sustain growth. As such we will one day, at least, have to learn to live with a steady, if not decreasing, population. “You cannot keep raising the bridge. At some point you have to lower the river.”

Well, were prices to rise “enough” then more housing would, presumably, be built where it is already allowed.

Well, I'm sure you'd agree, though, that there's an absolutely enormous difference between A) allowing the above to take place "anywhere" (like, say, a builder can buy four adjacent houses and put up 30 townhouse-style condos) and, B) making that illegal.

The "where it's already allowed" generally translates into areas requiring long commutes, so there's a deleterious environmental impact. But more immediately, fewer housing units gets built than would be the case under a strong "shall issue" system with respect to building permits. And that, in turn, ultimately translates into economic rents for incumbent owners. Which makes society as a whole poorer.

I would think though those four single family homes are the things to which those wanting to move to the location aspire rather than the thirty unit condo complex. Otherwise they would be happy to move into the 90 unit condo complex which replaces a thirty unit one.

I would think though those four single family homes are the things to which those wanting to move to the location aspire rather than the thirty unit condo complex.

If that's the case, there's no need to make such conversions illegal. But we do in fact make such conversions, illegal, in lots of neighborhoods, in many urban areas.

I believe the evidence strongly suggests that, in our most affluent and housing-scarcity-plagued metros (the two go hand-in-hand) in fact the demand for any well-situated (near jobs, amenities, transit) homes is generally white hot.

For the record I'm not suggesting we mandate density upzoning nor make it illegal to build detached, single family homes on large lots. I'm suggesting we simply make it legal everywhere for builders to meet the supply demanded by those who want homes. I think it's pretty clear in a lot of areas, families would be thrilled to be able to buy a home in a neighborhood that works for them, even if it doesn't come with an acre of land. (And if I'm wrong and there's little demand for townhouses or condo-style dwellings other dense styles, builders won't build such types of housing, so there's nothing to worry about!).

While the only thing constant in the world is change, you are basically saying it should be ok to surround Mister Fredricksen’s house with apartment buildings…

you are basically saying it should be ok to surround Mister Fredricksen’s house with apartment buildings…

Not sure I'd say it's ok (but "legal"? sure). What does "surround" mean specifically? The building is six inches from his house? 80 meters? Eight stories? Thirty stories? But yes, in general I think it should be legal to build apartments even in (pass the smelling salts) neighborhoods currently dominated by single family homes.*

AFAIK for the first 170 years or so of the Republic's existence, that was how it worked. It seemed ok, in large part because edge cases like the one you cite hardly ever happened. It's challenging to amass buildable plots in areas where land is pricey, and scary-scenario development doesn't seem to have much commercial appeal.

Although utility maximization isn't everything, it's not nothing, either, and it seems plain that formulating policy to prevent extremely rare hypotheticals doesn't justify making millions of people considerably poorer than they'd be if we, you know, simply made it legal to build shelter for them.

*For the record I have no issue with reasonable regulations wrt things like set back requirements, minimum lot size, height restrictions (if any), parking, and so on. I just think A) they really should be reasonable, probably based on objective criteria (like, say, current population density of the zip code, or census tract, or what have you, ideally formulated at the state level); and, B) we should abolish the arbitrary NIMBY veto. So, if you, Mr. Developer, have acquired a plot of land in an area that "qualifies" (according to aforementioned reasonable rules) for (say) a 5 story, 18 unit building, the construction permit "shall be" issued. Full stop. In much of America, even housing that qualifies under zoning rules can't be built. Because reasons (basically, neighborhood opposition). But no, in general I don't think it's desirable or necessary to switch to a system whereby vast swaths of single-home suburbia are destroyed to make room for giant residential towers in all directions.

Anyway, off to see Kevin's Twitter feed. Should be good!

Kevin - your basic argument appears to be the laws of supply and demand work (" When demand goes up, so do prices. When prices are forced down, supply goes down.").

The challenge with your point of view is that regulatory barriers materially limit housing markets, particularly in some high demand cities. In a 'free' market more housing would be built in desirable places (near employment or transport etc). Rather, because of structural limits (zoning, minimum lot sizes etc) supply is materially constrained.

Basically, housing markets reach an equilibrium that is artificial too low terms of supply.

He seems curiously indifferent to this. All you have to do is look at house construction in high productivity areas—California would be the obvious example—in, say, the 1960s, and compare that era to now, to see some vastly different practices.

Now, if you want to make the argument that the way we do it now (heavily constricted) is better, have at it. But it seems strange to fail to notice there hasn't been a big change. I don't have googled stats at the ready, but I'm pretty sure median house price as a percentage of median income has increased pretty dramatically in much of the country (way beyond accounting for size or quality differences). This alone is hard to explain away without acknowledging our laws make it harder to build housing, and harder to afford.

The housing market is so expensive that the day workers used to build new homes have no place to live.

I’d be curious to see something other than averages.

Because most places are cheap: the trouble is these places are small, scattered all over, and have poor job markets.

And then there are the big cities: these places are not cheap, but they have truly prodigious housing supply and a lot of jobs. But houses are expensive.

Indeed, if you are willing to move anywhere, finding a house is an optimization problem: maximize job potential and minimize price (I can’t life my life that way. But some people seem able.)

Sadly, the job absolutely has to come first.

I’d like to see some numbers on how that plays out.

My gut tells me: cheap housing usually means a poor economy. Some places are cheaper for more than just economy (it’s a terrible place to live), and some places are more expensive for more than just economy (it’s a great place to live).

But my hunch is housing prices are very highly correlated with job opportunities, not just preferences, and using averages all the time obscured that important fact.

That "truly prodigious housing supply" isn't prodigious enough. Population growth (to say nothing of household growth; we have fewer households per capita than previous decades) has greatly outpaced housing unit growth almost everywhere.

Housing is a free market? That is a bold claim that ignores pretty much every aspect of the housing market.

Housing's a free market if we ignore the fact that we've enacted laws against full participation in the purportedly "free" market.

Kevin seems to be arguing that supply responds to demand. This is true in many markets - if the price of widgets goes up, more factories will be built in China to make them. But housing in urban/suburban areas is no longer sensitive to demand - there is no longer land to build on, because most areas are already built up and there is resistance (zoning laws) to building more dense (multi-unit) housing. Despite record low mortgage rates - which are a primary determinant of offering price - since around 2012 until this year, the rate of house building per capita has barely reached the previous low points since WW II:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=Sbas

Real house prices and rent have gone up more than median income (which has been flat since around 1970):

https://listwithclever.com/research/home-price-v-income-historical-study/

So if it would be a good thing to bring house prices and affordability back down to how it was 60 years ago and to prevent things from getting even worse, we need a lot more houses - but there's no place to put them. Maybe the overall cost problem would be reduced if zoning restrictions were eliminated, but if the land went to multi-family dwellings the price of single-family houses in urban/suburban areas would probably go up.

...it would be a good thing to bring house prices and affordability back down to how it was 60 years ago and to prevent things from getting even worse, we need a lot more houses - but there's no place to put them.

No place to put them? Seems wrong. America has about 1/3rd the population density of France, one of the less densely populated countries of Europe, and I'm excluding Alaska. But France builds houses. There are plenty of places to put them in America. Tokyo in recent years has been green-lighting more home building than all of California, a jurisdiction three times larger than Tokyo.

America has made it illegal to adequately meet the demand for new homes. Full stop. It's a legal and political problem. It's not one of land scarcity.

(Yes, of course market forces suggest single family houses on large lots will get progressively more expensive to supply in many urban areas; the good news is Americans seem happy—eager, even—to snap up multi-family homes in all shapes and sizes, if we but allow builders to build them).

In 2019, France’s population was increasing by 0.2% per year. The US was at 0.5%. Japan was “growing” at -0.1%…

Yes, if you force people to buy densely packed housing, they will buy densely packed housing. The rich will still sprawl elsewhere.

Yes, if you force people to buy densely packed housing

I don't think anybody wants to "force" people to buy "densely packed housing" although their wallets might not stretch enough to buy single family homes on an acre these days (at least in the more prosperous parts of America, especially if they don't fancy a long commute).

I just want to allow such purchases to happen.

It's hard to see a national hosuing shortage in the statistics, but this is the wrong way to look at the compilation of 50 state or 400 MSA housing markets.

Cheap rent and extra housing in West Virginia, Michigan, Ohio and Kansas doesn't really impact the housing situation in California, Colorado, Florida, New York, etc....

National averages do tell us something, but this measure likely hides the situation facing the half (?) of the country living in the places that have demand for housing.

Rent to income by state (or by MSA)over time might show a very different picture?

Do you *really* not care whether you have a 50-story high rise or tennis courts next to your suburban house? I would certainly mind--but that doesn't mean I should necessarily be able to block the building that would dominate my environment.

Overall stats about housing units available in the whole country vs. demand mean nothing because there are local mismatches.

In Pittsburgh, much of the available housing stock is old and dilapidated and in less desirable areas, while there is a shortage in other areas that people want to live in.

"Nobody likes to say this, but the easiest way to increase supply is to let prices rise."

This may be true for markets that are easy for producers to enter. For several reasons this is not the case with housing: zoning restrictions, geographic limitations, the fact that people tend to own or rent housing for relatively long periods of time.

Also, Kevin doesn't mention this, but the numbers he uses imply an average household size of about 2.38 people per household. This may be reasonable in suburbs with many couples and families. But I don't think those numbers work for the cities that young single people want to live in. Many single people want to live alone. If you decrease the 2.38 people per household number the shortage of housing becomes more severe than what Kevin portrays. Conversely, for suburbs that have alot of families with children if you raise the number to say 3, the shortage would decrease. Overall I think that Kevin is underestimate how severe the housing shortage is. This is a very nuanced issue and applying the same formula to calculate housing needs for different locations, won't provide a clear picture of how big, or even what the problem is in different places.

In addition: the 2.38 people per household already accounts for a significant number of people who consider themselves to be a household of 1 even if they have roommates. They certainly don't file taxes together, for example, and aren't dependent upon each other. They just happen to live together.

62 years ago you could get a loan on a house that was 3 times of your yearly salary. For me that was 16.4K. $500 down.

I just sold a house that would require a yearly income of 700K to get a mortgage. If the same 1/3 ratio was enforce. The down was 1M.

The world is going to hell in a hand basket or the future is so bright we will need shades.

SIGH I'm going to be kind a suggest that Kevin is not having a good week. It's a trying time for so many of us.

Others have touched on the thoughts I have - housing is very much a local market so national averages are no good for digging into the whys like Kevin is attempting to do.

It's easy to scold folks for not moving but there's no safety net and moving is expensive so folks stick to the place they grew up in and lean on family when hard times hit. Other folks can't easily relocate because their career is tied to a specific geographic area - unlike say a nurse some careers need to be in certain locations.

In the DC area they say the market is cooling a bit but I'm not seeing any evidence of that. Houses in my neighborhood are still selling the week they are put on the market one right around me was sold before the open house. It's rare that a house sits on the market, either it's a house in a horrible location or the fill in mansions for well over a million that do take time to sell.

There's no undeveloped land to add housing, there's only redeveloping existing land to convert to apartment blocks or townhouses but it's not happening fast enough for folks who need housing.

DC area prices are falling, which is why they are selling.

Yeanope not in my zip code, they are steady to rising.

The current situation, that is rising prices of housing in urban/suburban areas, is largely a creation of the big businesses which naturally want to locate in existing urban areas. But maybe they are not properly factoring in the rising housing costs. When the so-called tech industries first began moving into areas like Silicon Valley, housing there was much cheaper. Could these companies and the financial industries find it to their profit to move into more rural areas? Business now is presumably much less dependent on face-to-face interaction and going to in-home employment could also allow movement of employees to less expensive areas. Of course if companies are going to do that they could use really low-cost employees in India and other places, which they are already doing.

You can define a housing shortage based on price and welfare grounds: rents/dwellings at the p% percentile quality/location range would consume over x% of income for people at the p% percentile range of income, where you might want x=30%.

You can also define a housing shortage based on efficiency grounds: for instance zoning or developer monopoly is stopping the supply increases so that price converges to raw/farm land price + construction costs + development contributions + FarmLandPositiveExternalityConsiderations.

"How much bread do we need? And who decides?"

"Let them eat cake."

Right now, the leftwonk panacea is housing. Don’t you dare suggest we won’t have heaven on earth if we don’t fill all the cities with lofts and art galleries.

More like centrist wonk. Leftwonk is conservation and resource constraint with housing in a isolationist system.

Strawman successfully defeated! Woohoo!!

Huh, I need all the econ 101 I can get so I'm glad for that, but it seems in this here modern economy it's not high prices that produces supply but rather large profits for those in the right place. Thus, it's not like rentable electric scooters were really expensive, so our cities suddenly were flooded with them, but we sure were flooded. Same with Uber, Wework, Social media companies, etc. I guess econ 101 would look at the scooter thing and say: well, thing that's high priced is convenient, short-distance transportation, so, scooters came in to make that cheaper.

Okay, I think what this points to is that the thing "no one likes to say" isn't that high prices will produce more houses (that seems to already be happening, to some degree), but that if we build a lot of housing (as seems wise) real estate developers are gonna make a lot of money.

Ok,

1. How in the world can Bakersfield have the most demand for housing stock on the chart?

2. Kevin alludes to this, but what progressives/liberals/Dems want is a housing policy which will, like zoning in general, result in more government mandated affordable housing built in otherwise un-affordable areas. Kevin's post basically just proves that expensive areas are expensive, which is true Captain Obvious.

3. While governments are at it, its not just affordable housing, its the whole panoply of solutions which allow for middle class housing in otherwise unaffordable areas. See, for example, Europe.

4. What we have is what you would expect if you let market forces go nuts. For example, Phoenix.

Because it doesn't measure potential demand.

Comparison of New Private Housing Units Authorized by Building Permits, CA, TX: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=SbCy

The problem with that metric is that those are houses that sold in a given period. You can get the same statistic with a falling home ownership percentage. Houses will appear to become more affordable, but fewer people will own them. Meanwhile, those who cannot qualify to buy have to rent, and rents are going up.

Another way you can get the same statistic is if housing is affordable in some areas but not others. The houses that sell will all be in lower cost locations while anyone in a higher cost location will be forced to rent.

What you are missing in this post is that supply *cannot* rise to meet demand, regardless of how crazy prices get, because it is *illegal*. Zoning codes make it illegal to build more housing in places where the demand for it is highest. YIMBYs are not just complaining about high prices, they are advocating the repeal of bad laws that prevent anybody from building and selling the homes they want to buy.

mr kevin just does not get the idea of saving the planet via containing urban sprawl and making walkable fun neighborhoods served by transit. small brain thinking.

https://twitter.com/QAGreenways/status/1541806669834858496?s=20&t=UNTRlr5r_vIAgPOxwWVjrg

Yeah, force everyone to live the same way. That's huge brain thinking.

No one said to force you to live that way.

But if rents for these units are higher, perhaps it's because there is a higher unmet demand?

Pingback: Сколько жилья нам нужно? - BORAO.RU - Хорошие новости

You lightly mention transit, Kevin, but completely ignore water supply issues. It sure seems odd that places that are rationing water are growing the housing supply.

What's the right amount of housing in Hawaii?

Who's rationing water, and what is the largest user of water there?

Check back when you know these things.

When we're making vastly fewer homes than kids, yes, there is a shortage. California made like 5x the number of kids than housing units in the last decade.