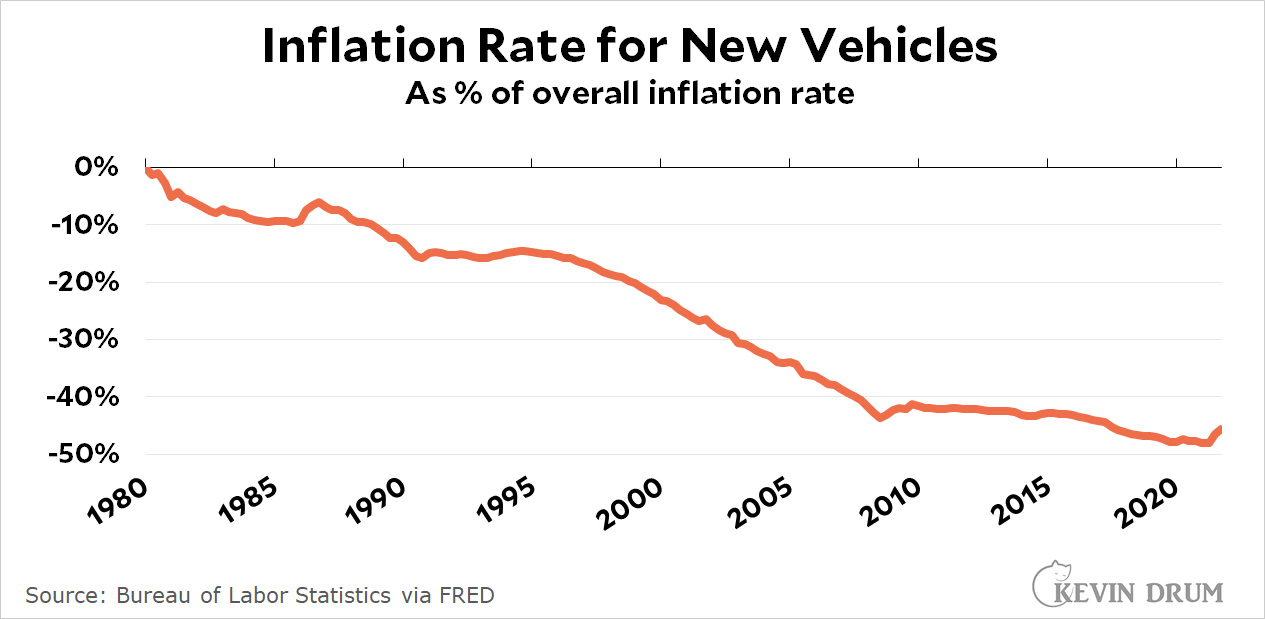

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, here's the inflation rate for new cars after it's been adjusted for the overall rate of inflation:

This probably looks very wrong. A Toyota Corolla cost about $5,000 back in 1980 and costs about $20,000 today. That's an increase greater than the overall rate of inflation, and it's typical of all cars. So why does the BLS say the inflation-adjusted price of cars has gone down by nearly half?

This probably looks very wrong. A Toyota Corolla cost about $5,000 back in 1980 and costs about $20,000 today. That's an increase greater than the overall rate of inflation, and it's typical of all cars. So why does the BLS say the inflation-adjusted price of cars has gone down by nearly half?

The answer is hedonic adjustments. The BLS measures not just prices, but also changes in quality. The price of that Corolla may have gone up a little faster than overall inflation, but the modern version has 17 airbags, antilock brakes, a navi-tainment system, a more reliable engine, and so forth. Essentially the BLS is saying that a Corolla costs roughly the same as it did in 1980 but you're getting twice as much car for your money.

Hedonic adjustments are applied to everything. In some cases, like loaves of bread, they don't make much difference. In others, like personal computers, they make a huge difference.

So how about health care? Everyone agrees that you have to make hedonic adjustments for health care, but the amount varies considerably depending on the treatment. An aspirin is an aspirin and requires no adjustment. Conversely, a friend of mine had a stroke a few years ago, but thanks to quick treatment with the latest technology he recovered completely by the next day. How do you measure quality improvements like this?

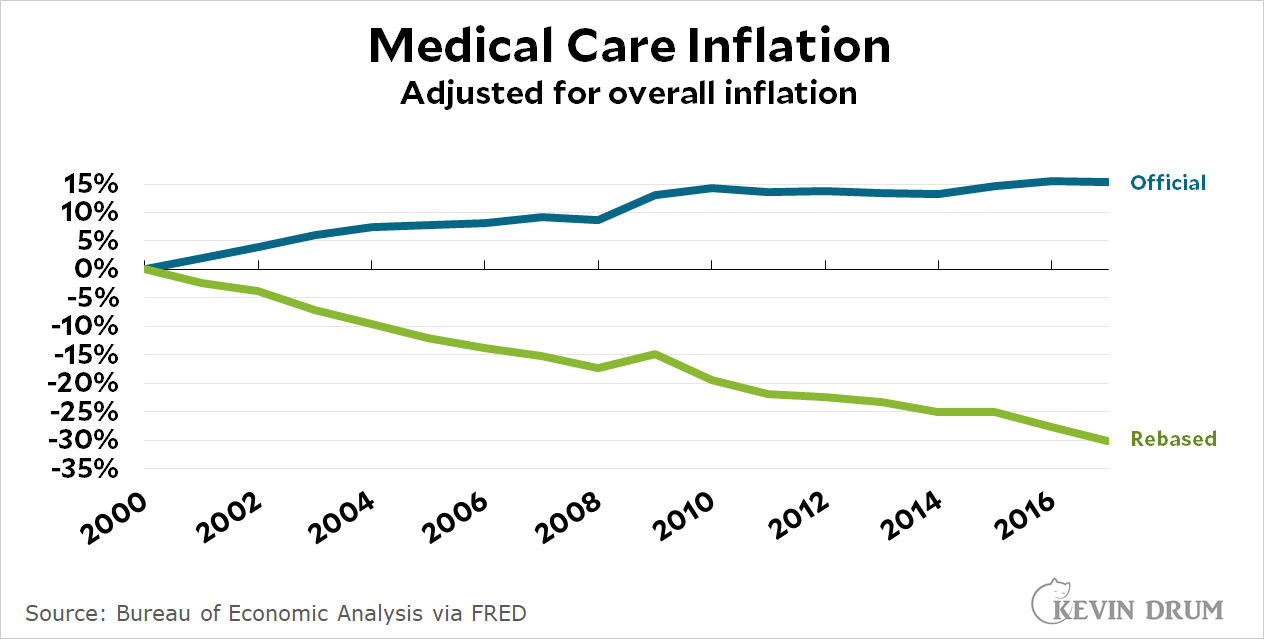

Tyler Cowen points to a new paper that uses a pile of cost-effectiveness data to do exactly this. It suggests that over the period 2000-17 the BLS has way underestimated quality improvements in health care and therefore way overestimated health care inflation. The authors illustrate this with a price index that's a little obscure and hard to replicate, so instead I'm going to roughly mimic their results using the ordinary PCE price index:

Very roughly speaking, official figures suggest that annual health care inflation has averaged about 0.8% above the overall inflation rate. But if you recalculate that number using the bias adjustment in the paper, prices have gone down by about 2% per year compared to overall inflation.

Very roughly speaking, official figures suggest that annual health care inflation has averaged about 0.8% above the overall inflation rate. But if you recalculate that number using the bias adjustment in the paper, prices have gone down by about 2% per year compared to overall inflation.

For the record, the numbers in the paper, which are based on a sectoral output price index and a complicated rebiasing formula, are 0.53% and -1.33%. However, there are a couple of reasons not to take the precise numbers too seriously:

- They are based on a database of quality improvements for individual procedures, along with an estimate of how widely these procedures are used and how much their increased efficiency has diffused throughout the health care industry. This obviously has a huge scope for error.

- The quality improvements are converted into QALYs, or the number of additional years of life that patients get from better procedures. However, the authors say their results are highly sensitive to estimates of the value of a single year of life. They use $100,000, but if instead they used $50,000 it would eliminate their main result.

So that's that. The authors conclude that the quality of health care has increased much more than official estimates, but even with painstaking effort this is always going to be a very difficult measurement to make. Even small changes in model estimates can balloon into large differences over the course of a couple of decades.

Still, it's an intriguing study. If the average treatment for a heart attack cost $100,000 in the year 2000 and provided five extra years of life, how does that compare to a modern treatment that costs $115,000 (adjusted for inflation) but provides seven years of additional life? The cost of the treatment is 15% more, but the cost per QALY has gone down 18%. So what's the right inflation measurement for that?

What if the hedonic adjustments are things you don't want and would rather not pay for? I'd rather be able to buy the 1980 Corolla. I don't want all those air bags, electronics, and safety crap that just breaks down. Seriously, I'm never buying a new car--just don't like them. I suspect some of the medical adjustments may be in the same league. For example, today's annual checkup is a multi-week ordeal of test after test after test after test, and then they tell you the same things: lose some weight, exercise more, drink less, keep an eye on it. You used to be able to get that advice after a 30-minute visit.

If that were my experience and my attitude, I'd stop getting check-ups. But it turns out that for many conditions (cancer, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, coronary artery obstruction), early diagnosis makes a huge difference, and those tests (and new ones coming online) facilitate early diagnosis.

"[A]ll those air bags, electronics, and safety crap that just breaks down" have decreased the motor vehicle fatality rate by 60% since 1980.

Indeed--Zephyr seems to be an old crank who wants to elevate old crankery to some sort of principled position. Reading their post, I half expected it to end with "And another thing--today's music is no good either!"

The point is that hedonic adjustments are very subjective, and my income hasn't been getting hedonic adjustments to match.

Ding ding ding!

Of course it's on some level subjective--that's the whole point. There isn't a way to compare costs of goods from different years if the goods themselves aren't the same without making an assessment of the value of the quality difference between those goods.

But what you're arguing is that somebody saying "well, a modern car costs twice as much, but it lasts longer and kills fewer people, so maybe it's worth 1.5x times as much based on xyz factors" is out of line because you personally don't care for fancy doodads on a car.

Nobody wants to pay for all the safety features, except the people whose lives were saved by the safety features or whose bodies weren't horribly damaged thanks to the safety features. Too bad we can't identify and only bill those people in advance, eh, Zephyr? Who knew scientific progress would produce so many financial losers in the Game of Life?

Well, "unwanted" medical improvements might include:

* excessive respect and solicitation by a whole horde of previously-unknown specialists, like "hospitalists", each of whom is paid per 2 minute visit and is probably out of your "network"

* the accompanying barrage of "satisfaction surveys" that the patient gets ... and the costs of tabulating them

* oh, and of course you don't get their bills for 2-3 months after the "visit", and not all at once so it's hard to compare the billing with actual services received

Recent experience.

A century or so back, it was not uncommon for people in their fifties to simply drop in the street with a stroke or a heart attack. If they didn't die on the spot, the ambulance would take them to their home, and their friends and family would gather for a last visit. Guys who made it through their fifties would probably last another decade, then at the Biblical three-score-and-ten some critical part would wear out and that would be that. Sure, you had the occasional nonagenarian, but those guys were extreme outliers. Myself, pushing the upper end of fifties, I take a handful of pills every morning and expect to keep going for another decade without any issues, and probably longer than that.

Many procedures, both for diagnosis and treatment, are enormously less invasive and unpleasant, not to mention more effective, that even 40 years ago - to say nothing about 60 or 70 years ago.

There's laser surgery and many other less invasive forms of surgery. A hip replacement today if vastly better than a few decades ago - less time in the hospital (usually one night) and it's good for 25 years instead of 10 or 15. A colonoscopy is a breeze today compared to the old style colonoscopies and barium enemas (ouch!). We have abortion pills, and COVID vaccines, and Viagra!

No way would I want to go back to 1980's medical care, or to trade my car for a 1980s model for that matter.

I agree with you on the cars*, but think you're missing the point on the medical advancements. The point of those tests (to catch things early) isn't related to the general advice that doesn't require tests to give you.

*Yes, to all the people commenting that SOME of the bells and whistles in modern cars have helped reduce fatality rates: please don't cite the reduction as being attributable solely to improvements in the cars themselves - there are other factors such as driver behavior as well as vehicle type (you're less likely to die in a larger vehicle, although much more likely to kill a pedestrian). More the point, many of the things resulting in the hedonic adjustments have almost nothing to do with life safety: navi-tainment (probably actually a minus to safety), back-up cameras, automatic parallel parking, OnStar and similar systems, better fuel economy, and so on.

Now, some of those things are worth paying for (better engine performance!), but I'm heavily on Zephyr's side here on the undesired extra functionality of what is, to me, stupid crap like automatic parallel parking and reverse cameras.

There's also the whole proprietary systems vs. right to repair shit - car manufacturers have a financial interest in making cars as complex as possible, and little financial interest in making no-frills versions. And yes, it absolutely sucks if you're a person who sees a car as merely a transportation tool and not a luxury space to be lived in.

This implies that for groups getting poorer medical treatment, medical inflation really is a problem: minority groups like Blacks, Native Americans and Hispanics.

My wife received a new hip about six years ago. I had some nerves in my heart blasted (from the inside) two years ago. Both procedures were in the $75,000-100,000 range. While my wife's surgery didn't save her life per se, it certainly made a drastic improvement in its quality. My surgery undoubtedly added several years to my life.

I think your examples are something of where the problem is.

For people like you, the advances are serious and clearly important. But they are in "serious" conditions.

For people like me (middle-aged) our medical conditions consist of colds and sore throats, weird inexplicable back pain, random headaches. And we're probably in the worst off position. We see all the downsides of modern medicine (dozens of specialists and tests) but little solution/improvement for our (admittedly minor, but still irritating) aches and pains. Needles have become sharper, which is great; but OTC pain killers are much the same as 20 years ago. There are more anti-histamine OTC medicines, but if claritin works well for you, the new ones don't seem any better. Back ache or vague "can't sleep well" remain great mysteries. etc etc.

I don't know we change that. The mass population seems incapable of appreciating basic probability, seeing insurance (or car safety features) as a scam, and the medical advances seem much the same -- "why should I care about better heart surgery, I'm never going to need it" - right up to the moment that I do.

I think this whole business of [presumably] calculating value/cost is interesting and important, but it belies a simple fact: when you measure the cost of something, that's simply what it says--how much does it cost?

All that other stuff is trying to normalize cost over value, but that's not what shows up on my bank statement every month. What shows up is how much I spent and how much I still have left. If my expenditures go up faster than my income goes up, then I have less left than I used to when my income was lower but my expenses were "more lower."

I was going to type that reply myself. It's cheeky to argue that healthcare costs are going down versus benefits when average folks are having huge out of pocket costs they can never repay.

hedonic adjustments are outrageous when used by the US government.

No where else in the world they are used for inflation statistic. When does that mean? US inflation is way understated compared to other countries and as a result US GDP growth is overstated.

No where else in the world they are used for inflation statistic.

Really? I find that hard to believe. This isn't some neoliberal plot. When you do comparisons, generally speaking you want to compare like to like. Comparing the cost of a circa 1994 cell phone to a circa 2019 cell phone would be meaningless without making the appropriate adjustments to account for the fact that these are two very different items.

If that were true it would show up as the dollar dropping in value compared to those other countries and it doesn't. It would also show up as the Corolla costing way more in US dollars than in Euros, and that isn't true either.

I think the OECD goes to some length to compare these things. Their figures may disagree with national figures, but not by enormous amounts.

Nowhere else you say?

https://data.gov.uk/dataset/9f837ab0-4508-4f91-bd14-92b7b9674f1a/review-of-hedonic-quality-adjustment-in-uk-consumer-price-statistics-and-internationally

Given that you don't know what you're talking about, I want bother looking for further countries.

GDP's can be compared either on the basis of currency exchange value or purchasing power (PPP) and there may be be considerable difference. For example Russia's GDP is very different with the two methods:

https://tradingeconomics.com/russia/gdp-per-capita-ppp

China also looks a lot better on a PPP basis. Determining purchasing power involves some of the same things as determining inflation rate, so these things are fairly well known.

Going back to cars it isn't just the extra airbags, cars last longer and need fewer repairs. You pay 20% more for that car but it lasts 50% longer and with less maintenance. Interestingly, I think, is some of that is due to catalytic converters.

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/18/automobiles/as-cars-are-kept-longer-200000-is-new-100000.html

Steve

mileage in 1980 (avg, cars and light trucks in US): ca. 15 mpg;

mileage in 2017 (latest numbers I can find): 22.3 mpg.

But the 2017 figures will be skewed by the massive increase in massive vehicles, like your pick-em-up trucks and SUVs. If those were removed, the remaining dramatically more efficient personal autos would look pretty good compared to the 1980 figures.

They may need fewer repairs on some things (like newer cars can go longer between oil changes if you use the right oil, higher quality parts last longer, the basic design of engines is the same but with those better parts, etc.), but I'm skeptical of the overall amount of repairs declining. I suspect it's remained much the same as more advanced components have been added - there's a lot more under the hood that can break now. Issues in the electronics/computer can also be harder to diagnose and repair than mechanical issues that you can see with an unaided (but experienced) eye.

Looking under the hood of my 1978 Jeep and 1997 F250 (engines in trucks of this vintage were slow to change), the engines are fairly similar. Even my 2001 Accord is similar, but it has a number of things added that those older engines just don't have, not least of which is the more advanced onboard computer. When you get into the 2010s with all the extra sensors, such as air pressure inside the tires, there are just a lot more things that can (and will) break over time. And of course, if you're like me and you're used to doing routine car maintenance yourself, air pressure sensors are a luxury that aren't worth the cost, but of course they do help people who don't do those things.

I believe one issue that complicates the picture just a bit (at least for me) is the paradox of medicine vs. medical coverage.

Most Americans most of the time* aren't receiving life-saving treatments. Even the preventative medical procedures they undergo (cancer screenings, say) aren't, strictly speaking, necessary (most of the time the results are negative!).

Now, obviously this should not obscure the fact that, yes, healthcare is a lot better and more effective than it used to be. And thankfully it continues to improve. And one of these days that cancer test isn't going to come back negative. And, given luck and enough time, the vast majority of us are eventually going to reach a point in our lives where we need heroic medicine. Maybe quite regularly. And we wouldn't have it any other way.

I'm simply pointing out that, for the bulk of Americans much of the time, the financial cost to themselves personally amounts to the cost of being covered (not the actual treatments they receive in real time). The peace of mind that accompanies healthcare coverage—and its implications for financial security—are something that hasn't really improved in decades. I mean, is knowing that you won't lose your house in 2022 a different and improved experience over what knowing that you wouldn't' lose your house in 1980 was like? And yet the financial impact is: it's a lot more expensive in real terms. I've always found this effect something of a paradox.

*This obviously is an age-sensitive datapoint, but even in 2022 about 85% of Americans are under 65, and about 2/3rds of them are under 50.

TLDR: For most people most of the time, the cost of coverage is what they experience in financial terms, and that cost goes ever upwards, with no commensurate, experienced increase in quality or effectivness.

Hedonic adjustments are brutally wrong. What does it matter if the 2022 car is better than the 1980 car when so many Americans can't afford the 2022 car? Same goes for medical treatment: what does it matter that medical treatments have improved so much to those people who can't afford the medical treatments?

Without hedonic adjustments, you're saying that you'd be OK with an insurance company replacing your 2021 Jeep Grand Cherokee totaled in an accident with a 2001 Jeep Grand Cherokee.

Most people would not take that "deal" but YMMV I guess. Just be aware that ditching hedonic adjustments in government stats will lead invariably to insurance companies ditching it for when you make a claim for damages to your property.

No, Austin, that's not what anybody is saying.

I'd be OK with my insurance company replacing my 2021 Jeep Grand Cherokee totaled in an accident with a 2021 Jeep Grand Cherokee, even though Jeep has brought out new, better Grand Cherokees since then.

OK. So why shouldn't hedonic adjustments be made then? If it's cool for insurance companies to use it - to be required to not just replace your 2021 Jeep Grand Cherokee with any other Jeep Grand Cherokee but a Jeep Grand Cherokee with all the bells and whistles that your damaged one had - then why shouldn't the government also use hedonic adjustments to account for the fact that sometimes goods just are much better today than they were in the past and that might be part/all of the reason why they cost more now vs then?

No, Austin, that's not what anybody is saying.

Well, given that in 1980 about 13% of American households did not own a car, whereas in in 2022 that number is about 9%, this does not seem like a serious objection...

hmmmm....

Average lifespan has increased from 76.75 to 78.93 over that time period.

Median household(not individual) income in US in 2020 is $69.5K.

Certain procedures and breakthroughs have certainly helped some people, e.g. childhood leukemia, aids, etc. But a lot of the costs are still in the last year of life, and may even make quality of life worse. I'm hearing on NPR in the background about lack of access to pre-natal care in rural (poor in general) communities.

(a) Lifespan is always a backwards looking measure. It captures the improvements that have become widely used, and that kicked in quite a few years ago; but doesn;t capture the newest improvements.

(b) Are you talking about lifespan or life expectancy at birth or some other measure? The general population treat these all as synonymous, but they are different and respond differently to changes in society; and people with an axe to grind will deliberately choose an inappropriate measure to further their agenda.

Consider a histogram of age at death. You'd expect this to be low up till about 60 or so, then to rise. But substantial changes in all that piled up probability on the right hand side are poorly captured by traditional statistics. Essentially the unimportant stretch from just after birth till about 60 "dilutes" the improvements we see on the right hand side.

(c) Essentially futile end-of-life interventions are a big issue, sure. But not captured by death statistics are QALY (*quality-adjusted* life years). My guess is those are substantially improved in terms of things like better daily maintenance meds, better bone implants, better life after stroke or heart attack or cancer, etc. However I don't know this literature well enough to find a simple graph or table showing whether/how this has improved.

If you look at the WHO tables, they give life expectancy from the time of your current age. To use the example above, if you just turned 70 then -- all other things being equal -- your life expectancy is 8.93 years.

I just did some quick googling: according to what I could learn, the price of the average new car since 1980 has gone from about 40% to about 60% of median household income. Make of that what you will.

Same thing holds for homes too. They gobble up more of median household income in 2022 vs 1980. Most people still exhibit a preference today for homes built in 2022 vs 1980, in particular because homes built in 1980 are generally viewed as crappier construction compared with ones built later or even earlier (homes built a hundred years ago are sturdier). And - even if the 1980 home wasn't cheaply thrown together - the style/layout of 1980s homes isn't as "timeless" as those built a century ago nor as "trendy" as those built today.

Make of that what you will, but it's really obvious that homes built in the 1920s are valued differently from those built in the 1980s which in turn are valued differently than homes built in 2020s. They really are different products all labeled "homes" that defy comparison to each other, other than in a really basic sense of them all being "places that humans are sheltered from the elements."

I would venture a guess that cars from the 1920s and 1980s (if they still run) are valued very differently from cars from the 2020s. They all are "things that people use to privately move from place to place" but they aren't really all the same otherwise.

Same thing holds for homes too. They gobble up more of median household income in 2022 vs 1980

That's the really the key: affordability. Some things have gone up in real terms, even if they're qualitatively better. So we can discuss just how much of a hedonic adjustment needs to be made. Conversely, though, plenty of things have gotten cheaper in real terms. I reckon through 2019 we'd see pretty sizeable drops (over 1980) in the price of: TVs, most home electronics, furniture, appliances, phone calls, airline travel, food, and clothing. By contrast housing, childcare, healthcare, education and (apparently) cars have gotten more expensive in real, non-hedonic terms.

I'm sorry to inform you that homes in 2022 are (mostly) built with even lower quality materials than those in 1980.

It's actually not obvious that homes built in the 1920s are valued differently than those build in the 1980s: price per square foot doesn't vary that much based on age alone. There is some survivorship bias in play (the older homes that are still around tend to be higher quality than those that aren't), but that's irrelevant to the price argument.

I tend to make it that Americans are willing to overspend on cars - actually light trucks (which includes SUVs). It isn't just a matter of inflation, it's also higher expectations about their vehicles. How important it is to their choice of lifestyles

The attitude is: I want my F-150, not a Toyota Sentra. And if I have to pay more, that's okay.

The same thing is true in housing. Increased expectations of what we consider a decent-sized place, what kind of quality fixtures, location, etc.

Trivia: The average-sized new home after WW2 was about 1,000 square feet, the average new home is now 2,500.

Hmmm, perhaps we should factor in increases in single family homes size as it relates to housing inflation...

That's meaningless if either

- cars last substantially longer OR

- it's cheaper to buy a quality second hand car.

In the space of cell phones (where the numbers are smaller, but we all have more experience) it's clearly true that

- the most expensive phones have got more expensive BUT

- a low-end "good" phone (bottom of the iPhone range for example) has stayed flat in price

- people can hold onto their phones for longer if they want to. iPhone around 2010 was massively inferior to 2013, but 2019 to 2022 is not nearly such a jump, and the worst failure modes of the past (like battery expanding or failing) have become less prevalent.

- if I can't even afford a new iPhone SE3, well I can go to eBay and find *something8 at a variety of price points

Surely the orginal product must be available to the consumer in some for or another for these comparisons to be meaningful; let's see how many people buy the 1980 version of the Corolla vs the ones who buy the 2022 model, for example.

I would think -- silly me -- that what customers revealed preferences say about any hedonic adjustments would have to count for something, right.

Plus, it's Tyler fucking Cowen fer goddsakes; who cares what that attention-seeking glibertarian idiot has to say?

I had the same thought, although we should remember that this is a paper and not Cowen's own research.

Still, Tyler Cowen is choosing to highlight it. Why? Are there other papers studying this? If so, is this one an outlier that he's highlighting to serve his anti-commoner agenda?

I'll let Kevin do the research on whether or not this one is an outlier in terms of quality and motivation 😉

Until then he's automatically presumed guilty beyond a shadow of a doubt, at least in my book.

Obviously what goes into the "basket" of things that price indexes use is arbitrary, as are the hedonic adjustments. Although according to the CPI real wages for "production workers" have not gone up since 1972, those workers now have things that didn't even exist in 1972. This makes it fairly meaningless to claim that one index such as the PCE is better than another such as the CPI. The meaningful thing about wage comparisons is that either nominal or real wages kept up with either nominal or real GDP/capita (or productivity) throughout US history up to the late 60's, but have fallen far behind since then, and inequality has increased enormously.

Likewise there is a meaningful comparison that must be made in health-care expenditure, and it is with expenses in other countries. On average those countries get equal or better care - and more equitable care - with about half the expense. Quibbling about hedonistic adjustments draws attention away from the important comparison.

Frankly, starting to think there needs to be a series for Inflation that is marked up in similar fashion to how Unemployment has a wide variety of measures. Add in a few Sectors as well.