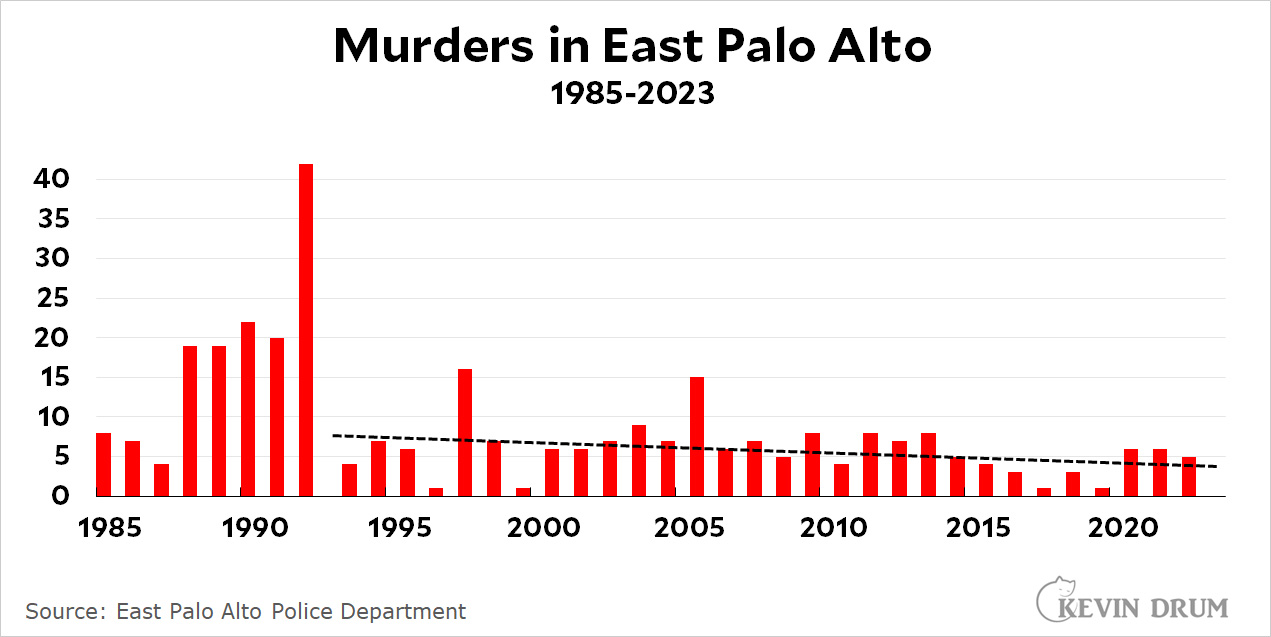

The Wall Street Journal reports today that office vacancies are at their highest level since records began:

A staggering 19.6% of office space in major U.S. cities wasn’t leased as of the fourth quarter, according to Moody’s Analytics, up from 18.8% a year earlier. That is slightly above the previous records of 19.3% set in 1986 and 1991 and the highest number since at least 1979, which is as far back as Moody’s data go.

Leases are a lagging indicator. They're usually signed on a long-term basis, so even when workers stop coming into the office the space remains under contract for years. Eventually, though, the leases expire and they don't get renewed. That's been happening ever since 2020 and there's no reason to think it won't continue. Evidence suggests that the number of office workers has declined by half since the start of the pandemic, and leased space has nowhere near caught up to that.

As you can see in the chart, unleased space peaked previously in 1986, four years after the end of the Reagan recession—and that recession didn't see nearly the drop in office workers that we've seen in recent years. Even if big companies start requiring more workers to come in, we still have a long way to go before leasing catches up—and in the meantime that's going to be a big drag on the economy.