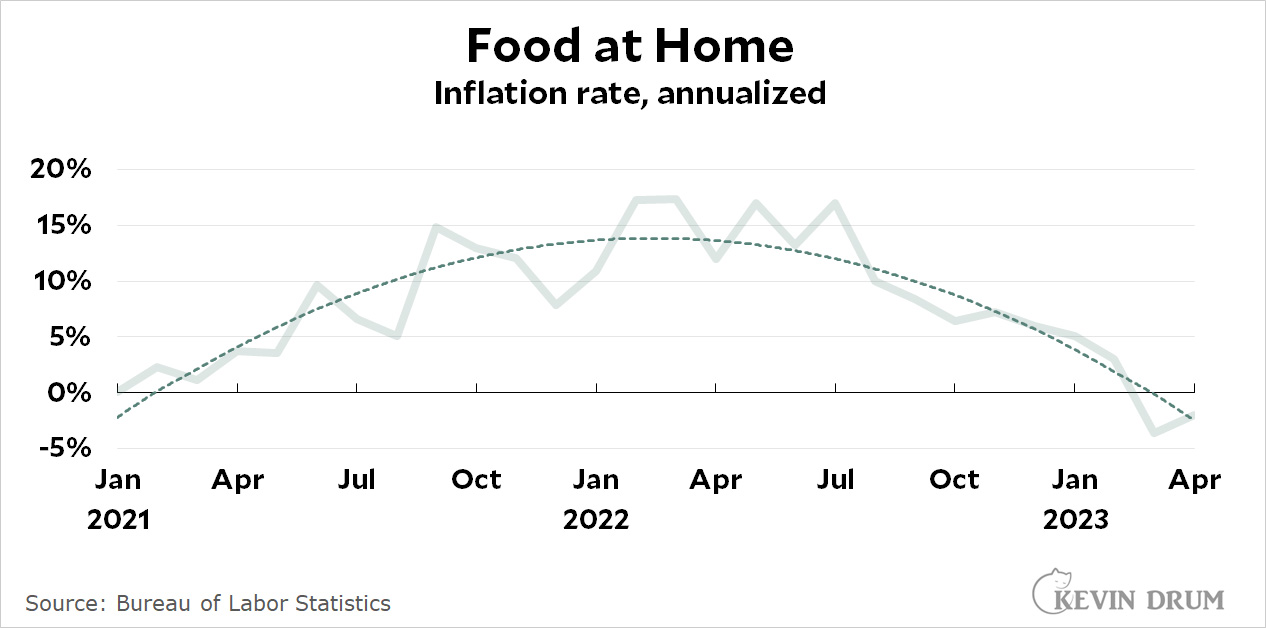

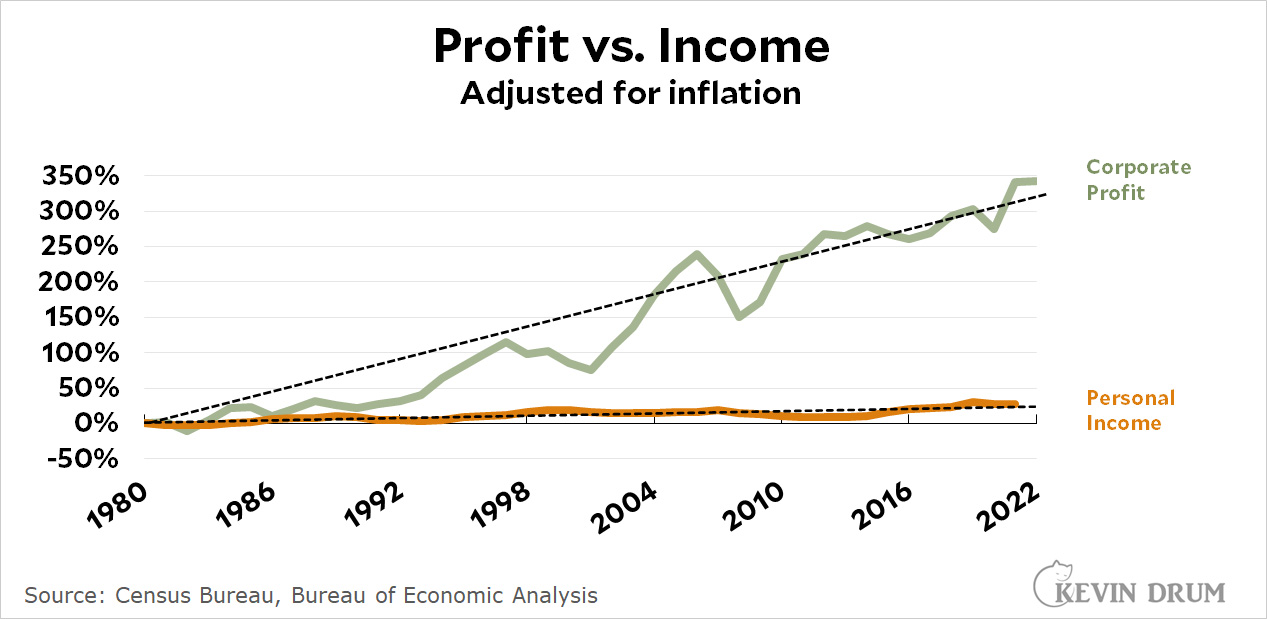

The New York Times writes today about greedflation:

PepsiCo has become a prime example of how large corporations have countered increased costs, and then some.

Hugh Johnston, the company’s chief financial officer, said in February that PepsiCo had raised its prices by enough to buffer further cost pressures in 2023. At the end of April, the company reported that it had raised the average price across its snacks and beverages by 16 percent in the first three months of the year. That added to a similar price increase in the fourth quarter of 2022 and increased its profit margin.

It's become common among large corporations to raise prices far in excess of inflation simply because they can. But why can they?

David Beckworth, a senior research fellow at the right-leaning Mercatus Center at George Mason University and a former economist for the Treasury Department, said he was skeptical that the rapid pace of price increases was “profit-led.”...Mr. Beckworth and others contend that those higher prices wouldn’t have been possible if people weren’t willing or able to spend more.

....“It seems to me that many telling the profit story forget that households have to actually spend money for the story to hold,” Mr. Beckworth said. “And once you look at the huge surge in spending, it becomes inescapable to me where the causality lies.”

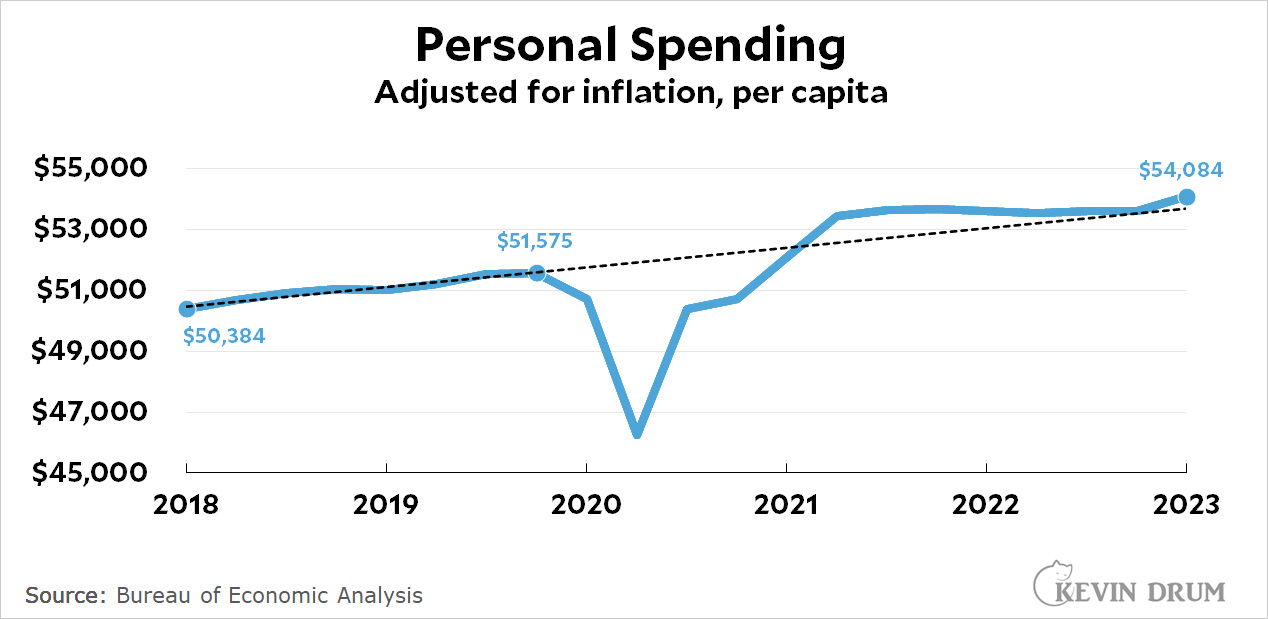

So has there been a surge in household spending? That depends a bit on how you look at it:

On the one hand, it's true that personal spending, even adjusted for inflation, has increased a lot since the start of the pandemic. Spending today is $2,500 higher than it was at the start of 2020.

On the one hand, it's true that personal spending, even adjusted for inflation, has increased a lot since the start of the pandemic. Spending today is $2,500 higher than it was at the start of 2020.

On the other hand, there's nothing unusual about this. Spending has just followed its usual trendline.

But trendline or no, this suggests that Beckworth is on to something. It's one thing to wantonly raise prices above the level of inflation in search of windfall profits, but you can only do it if consumers don't push back—and if they don't push back then you might as well charge all that the market can bear. And right now it looks like people are spending money freely enough that the market can bear quite a bit.