Two guys hanging out on La Brea Ave. in Los Angeles. Don't forget to file your taxes this week!

Cats, charts, and politics

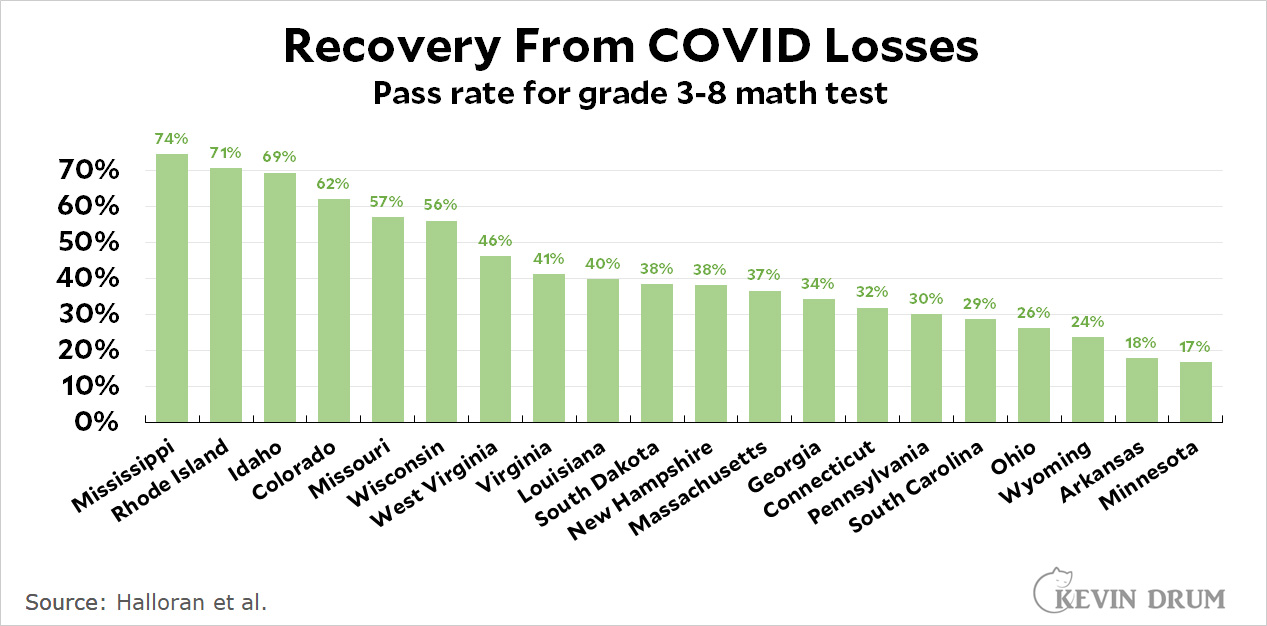

It's well documented that schoolchildren lost a significant amount of learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. A new NBER study attempts to figure out how much of that they made up in 2022. Their metric is the percentage of students who scored "proficient" on state tests. Here are the results for math:

Of the 20 states in the study, Mississippi made the strongest recovery. Their pass rate is now close to what it was before COVID. Minnesota was the worst. However, every state showed at least some recovery. The same is not true of reading:

Of the 20 states in the study, Mississippi made the strongest recovery. Their pass rate is now close to what it was before COVID. Minnesota was the worst. However, every state showed at least some recovery. The same is not true of reading:

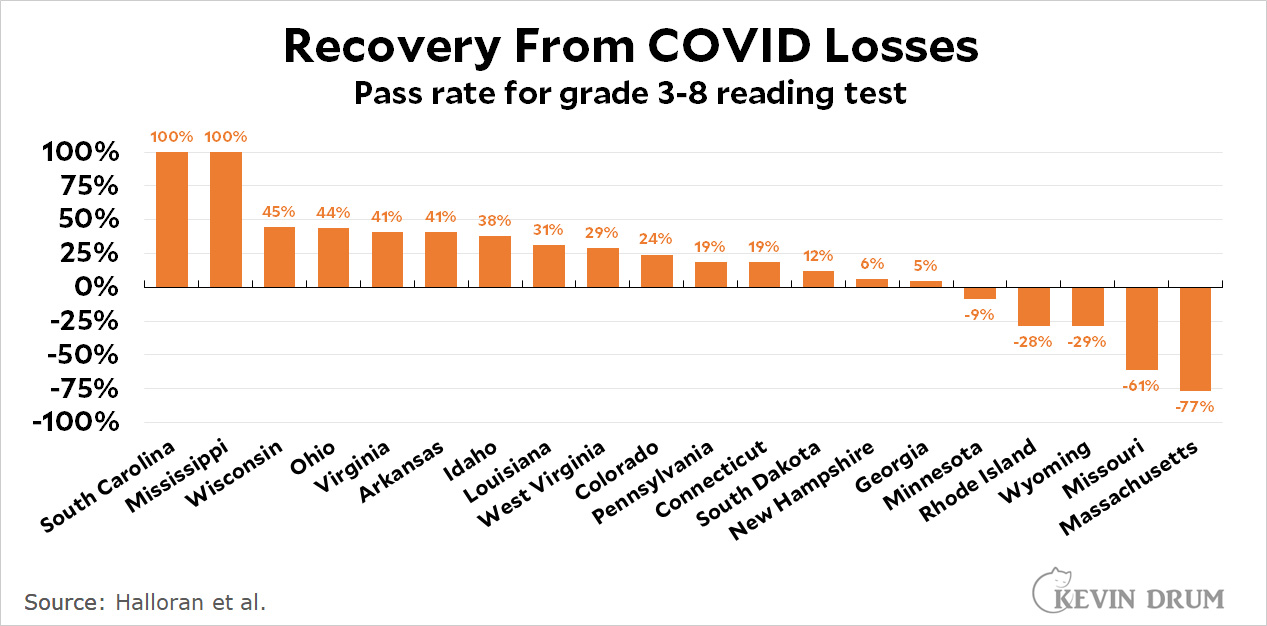

Two states, South Carolina and Mississippi, have made up all their losses and now have a higher pass rate than before COVID. However, five states continued to decline. Massachusetts went from a 52% pass rate to 45% during COVID and then dropped 41% in 2022.

Two states, South Carolina and Mississippi, have made up all their losses and now have a higher pass rate than before COVID. However, five states continued to decline. Massachusetts went from a 52% pass rate to 45% during COVID and then dropped 41% in 2022.

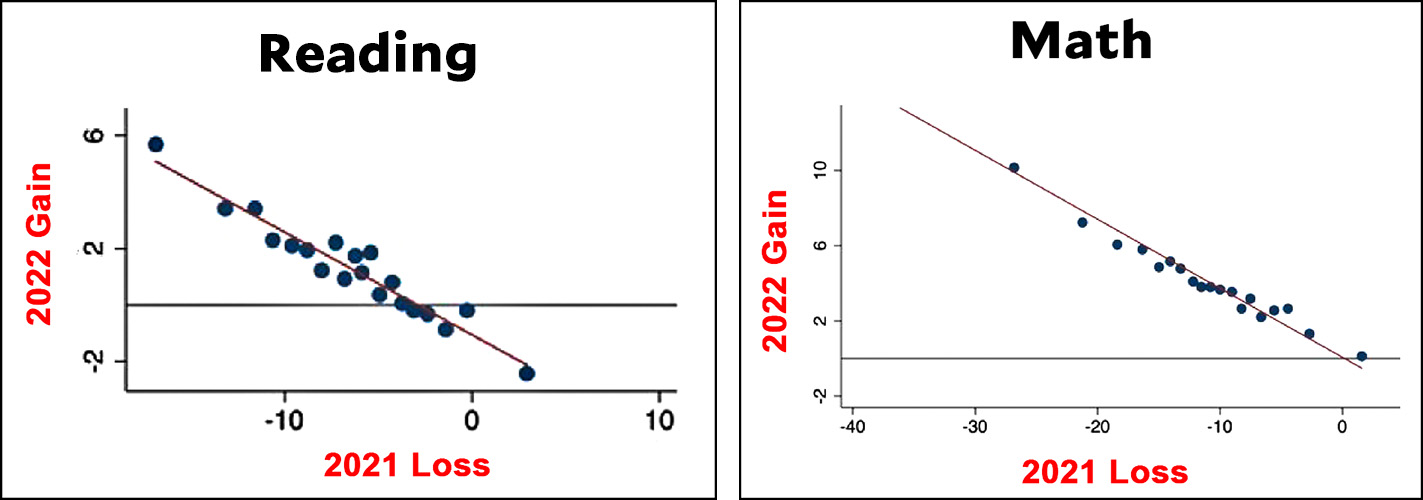

The size of the difference between states is remarkable. But this chart suggests it might be easy to explain:

This is a binned scatterplot done at the district level (not the state level). The conclusion is plain: the bigger the loss in 2021, the bigger the gain in 2022. However, the correlation is extremely tight, which makes me a little suspicious—especially when we see no such thing at the state level:

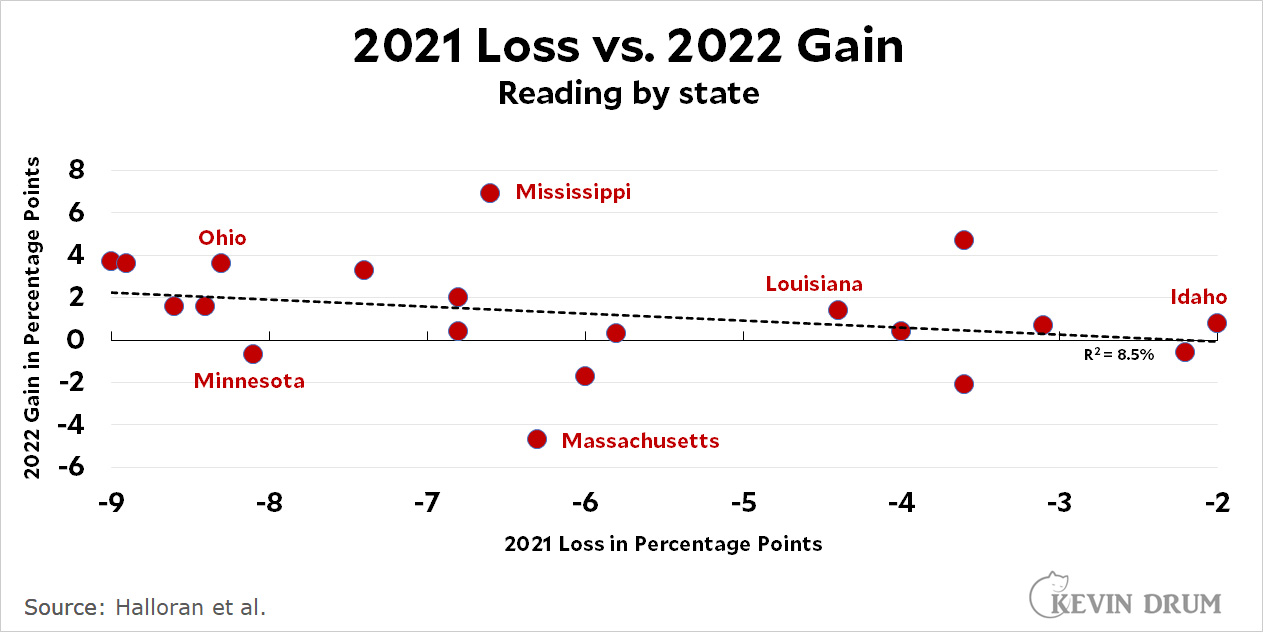

This is a binned scatterplot done at the district level (not the state level). The conclusion is plain: the bigger the loss in 2021, the bigger the gain in 2022. However, the correlation is extremely tight, which makes me a little suspicious—especially when we see no such thing at the state level:

There's only the slightest correlation between gains and losses at the state level, which is where education policy is set. So this probably doesn't explain much. Furthermore, the study's authors dug into a bunch of other possible explanations for the wide variance in state results, but none of them panned out. For now, it's a mystery.

There's only the slightest correlation between gains and losses at the state level, which is where education policy is set. So this probably doesn't explain much. Furthermore, the study's authors dug into a bunch of other possible explanations for the wide variance in state results, but none of them panned out. For now, it's a mystery.

For some reason I decided to torture myself and read yesterday's New York Times focus group with twelve people in their 70s and 80s. Here's my favorite part:

Earlier, someone mentioned Dianne Feinstein, the senator from California, who has served for nearly 30 years. She just announced she’d be retiring from the Senate. Does anyone have a strong view one way or another about that decision?

Eugene, 80, Calif., white, Republican, retired

She should have done it two election cycles ago.Why do you think so?

It was three election cycles ago that we voted $3 billion to provide for reservoirs and water for the state. That remains unspent.

So it’s about effectiveness in office, Eugene?

Oh, yes.

It's true that in 2014 we voted to spend a bunch of money on water projects. It's also true that these projects take a long time to approve and build. Most of them aren't scheduled to become operational until the end of the decade.

Maybe that sucks, or maybe it's just business as usual. Either way, though, Dianne Feinstein is a US Senator and has nothing to with it. But Eugene is mad at her anyway.

Last night the conversation at dinner somehow turned to the subject of education and the South. No conclusions were reached except for a vague agreement that Southern states didn't spend a lot on education and had generally poor outcomes.

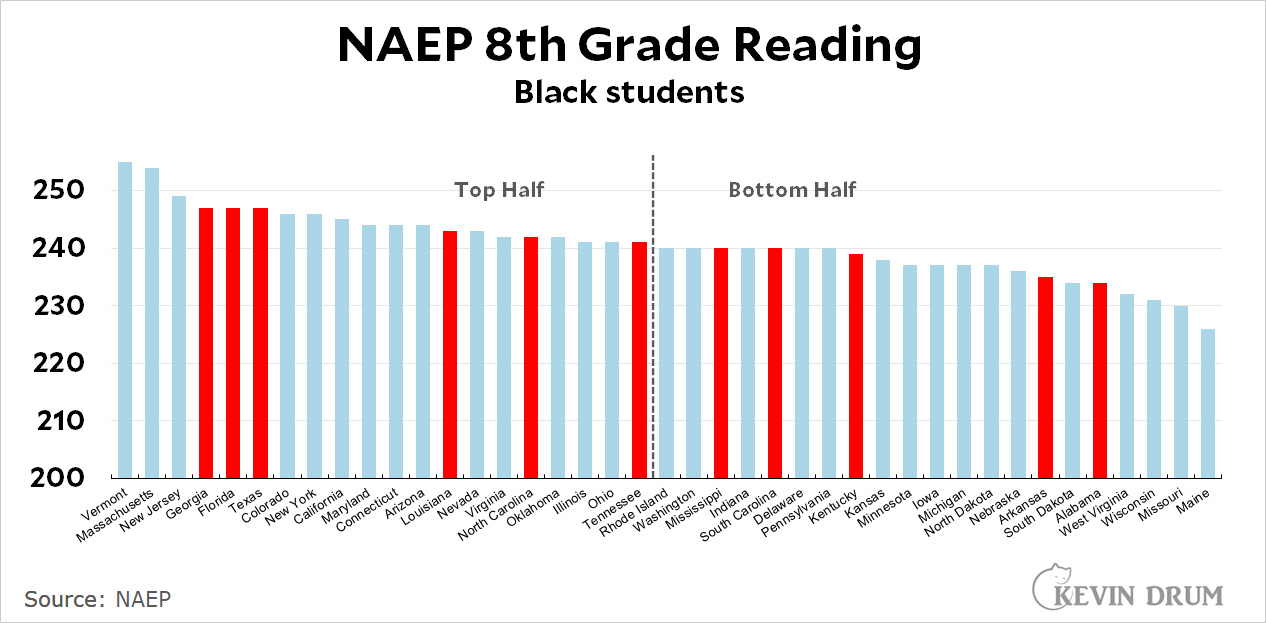

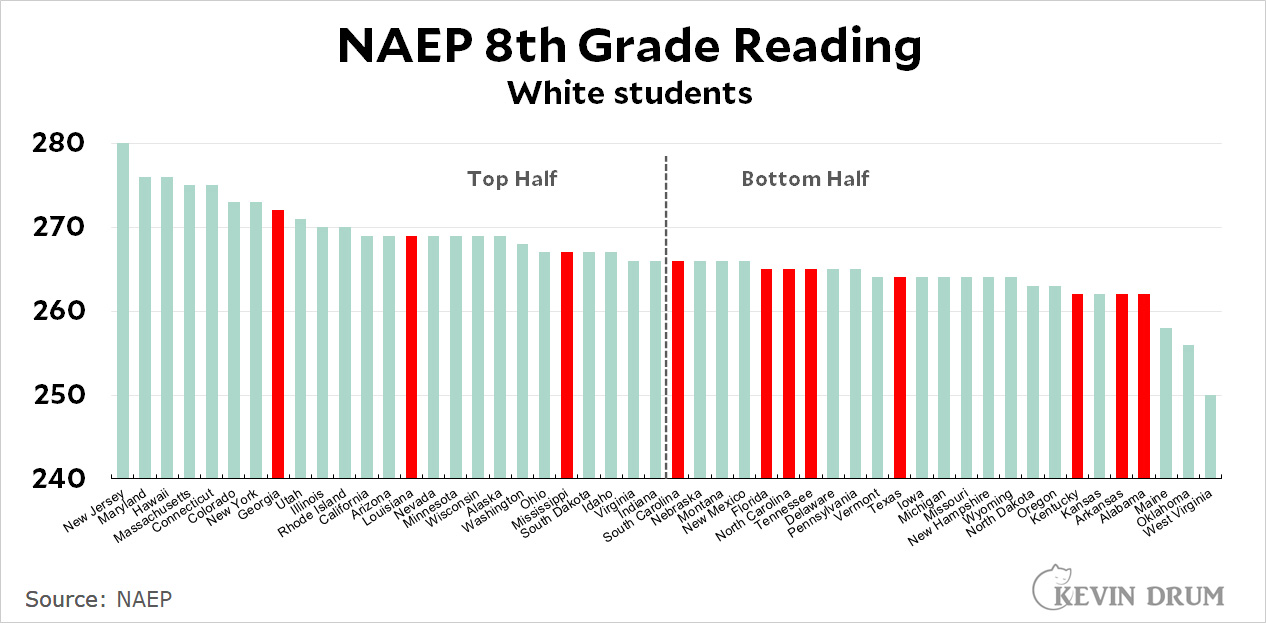

But is that true? Naturally I decided to check. My metric is 8th grade reading scores on the NAEP because (a) 12th grade scores are old, sparse, and cover only a few states, and (b) reading scores are a better reflection of general education than math scores. Here are the results separately for Black and white students:

All the usual statistical caveats apply here, and this should hardly be taken as the final word. However, one possible confounder that I checked out specifically was private school enrollment, which turned out to be about the same in the South as everywhere else.

All the usual statistical caveats apply here, and this should hardly be taken as the final word. However, one possible confounder that I checked out specifically was private school enrollment, which turned out to be about the same in the South as everywhere else.

The perhaps surprising result of all this is that, relative to other states, six Southern states are above average when it comes to Black scores. Only three are above average when it comes to white scores. I'm not quite sure what to conclude from this.

In any case, when you look at the results for all students it turns out that Southern states are unexceptional. As a group, their reading scores are slightly below average (256 vs. 259, a gap of about one-third of a grade level), but nothing more than that. Among Black children, the average score for Southern states is very slightly above the US average (241 vs. 240).

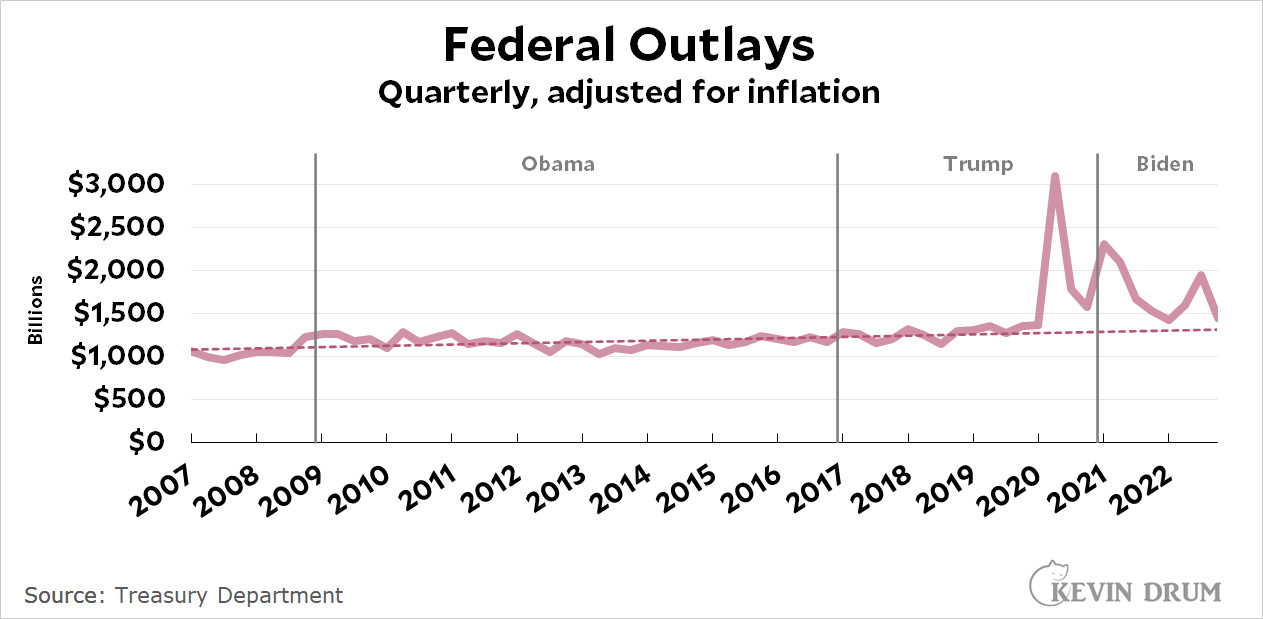

Over at National Review, Philip Klein takes in the news that payments on the federal debt have gone up thanks to higher interest rates. Along the way he says:

Under President Biden, massive spending has fueled not only high deficits but also inflation.

Let's take a look!

It looks to me like both Biden and Mitch McConnell spent a big slug of money,¹ and of course they did so for a reason: COVID-19. As the COVID emergency has waned, so has federal spending, which is now back to its longtime trend.

It looks to me like both Biden and Mitch McConnell spent a big slug of money,¹ and of course they did so for a reason: COVID-19. As the COVID emergency has waned, so has federal spending, which is now back to its longtime trend.

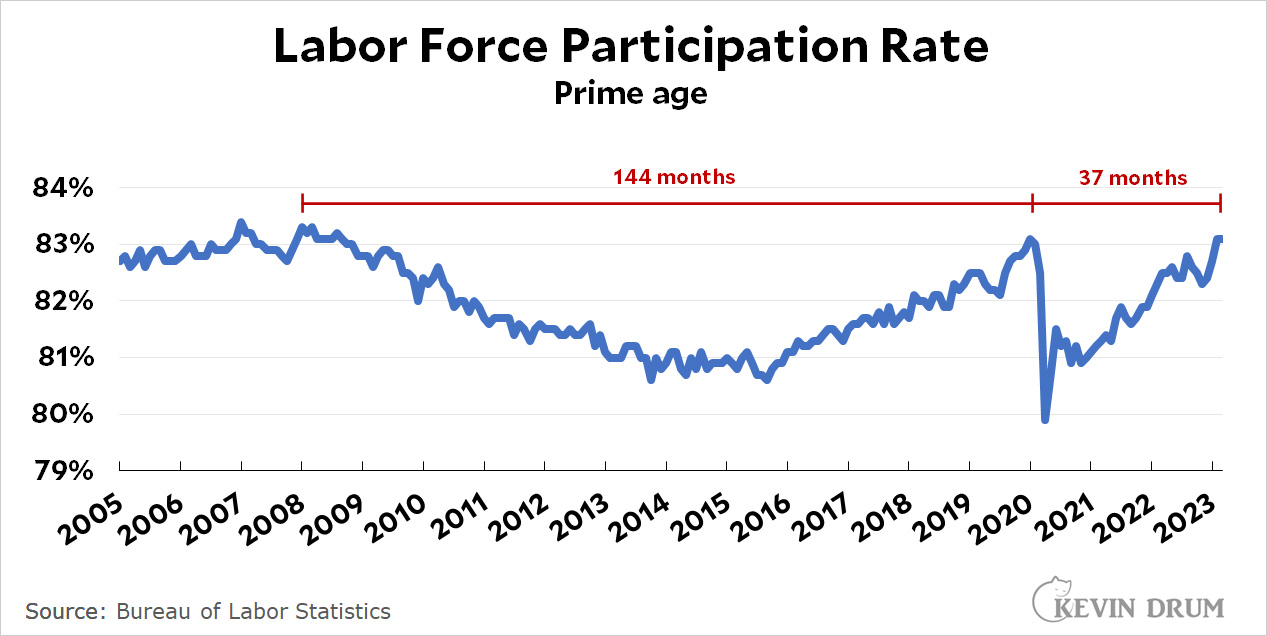

So let's put a cap on the nonsense, OK? If high spending is indeed responsible for our inflation spike, it's as much the responsibility of McConnell as Biden. But if a year of inflation is the price of a spending policy that kept the United States on the path of growth and full employment, it was worth it. As Paul Krugman points out today, COVID emergency spending is the reason that employment took only 37 months to recover compared to the 144 months it took to recover from the Great Recession:

This looks like a pretty good tradeoff to me. It's something to be proud of, not ashamed of.

This looks like a pretty good tradeoff to me. It's something to be proud of, not ashamed of.

¹Normally I would have said "Biden and Donald Trump," but I couldn't bring myself to pretend that Trump played any role in this. He was too busy at the time figuring out ways to make sure he didn't take the blame for the pandemic.

On Saturday I was up in LA on a variety of errands. My last stop was the Westlake/MacArthur station near MacArthur Park, where I wanted to check out the blaring classical music being played to keep the bums out. Was it really loud enough to count as torture?

Two caveats. First, MTA might have turned down the volume since the LA Times ran its story last Tuesday. I have no way to know. Second, I recorded my visit on my phone, which doesn't do a very good job of recording ambient noise. Or, more accurately, it does too good a job of recording ambient noise. Metro stations are fairly loud places, with air conditioning and machinery noises echoing through a cavernous space, but it's not as loud as the video makes it sound. That said, the music wasn't really especially annoying. In fact, it was hard enough to hear that I couldn't tell you what it was. Now, however, you may judge for yourself.

UPDATE: Yep, the volume has been turned down.

Over the weekend I observed that conservatives have been notably silent about the flaky legal reasoning behind Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk's nationwide ban of the abortion pill mifepristone. Today, National Review's Michael New takes a different approach: instead of trying to defend Kacsmaryk's ruling on legal grounds, he claims that mifeprestone is, in fact, more dangerous than you think:

On April 1, the New York Times published a thorough analysis of the research on chemical-abortion drugs. They conclude that a vast majority of the academic studies show that chemical abortion drugs do not pose a significant health risk to women.

OK then! So what's the problem?

However, much of the research on the Times article is not relevant to current risks of chemical abortions obtained in the United States. That is because, on multiple occasions, the FDA has instituted policy changes that likely increased the health risks involved with the chemical-abortion-pill regimen.

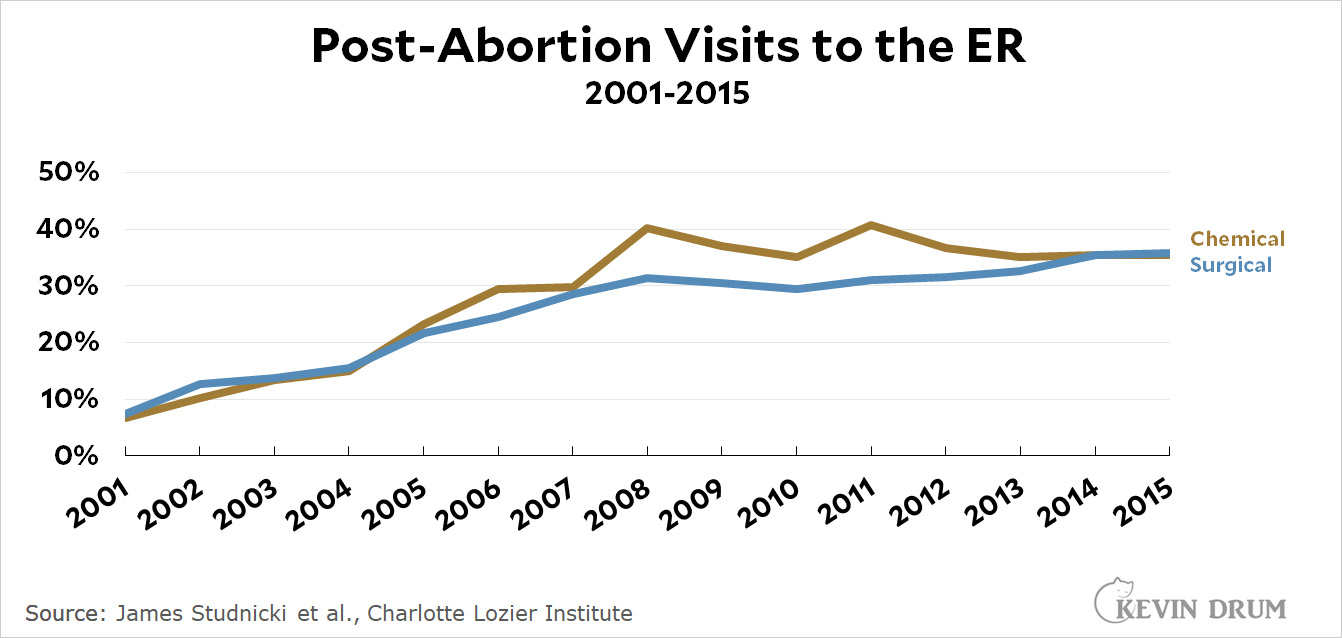

....A November 2021 study by Charlotte Lozier Institute scholars appeared in the peer-reviewed journal Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology....They found that the rate of abortion-pill-related emergency-room visits increased over 500 percent from 2002 through 2015. The rate of emergency-room visits for surgical abortions also increased during the same time period, but by a much smaller margin.

That sounds like a lot. Let's go straight to the data:

I assume that New's use of 2002 was a typo since data goes back to 2001. During the period of the study, the number of ER visits for chemical abortions increased 532% while the number for surgical abortions increased 488%.

I assume that New's use of 2002 was a typo since data goes back to 2001. During the period of the study, the number of ER visits for chemical abortions increased 532% while the number for surgical abortions increased 488%.

Is that a "much smaller" margin? You can be the judge of that.¹ However, the number of ER visits in 2015 stood at 35.5% for chemical abortions vs. 35.8% for surgical abortions.

This all comes from the Charlotte Lozier Institute, the research arm of Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, a group dedicated to electing anti-abortion candidates. Even so, I guess this is the best they could do on mifepristone. I'd say that its reputation as a dependable pharmaceutical is safe for now.

¹For what it's worth, the entire difference is due to a single ER visit in 2001. If, instead of one ER visit that year following a chemical abortion, there had been two, the increase in ER visits through 2015 would have been 266% compared to 488% for surgical abortions. This is a demonstration of the power of cherry picking increases from tiny starting numbers.

Here's the latest from Texas. During the summer of 2020 an Army sergeant named Daniel Perry was upset about a nearby BLM protest. He wrote to a friend on social media that he might “kill a few people on my way to work. They are rioting outside my apartment complex.”

The friend, naturally, asked, “Can you legally do so?” Perry said he could: “If they attack me or try to pull me out of my car then yes.”

Perry proceeded to put this plan into action. He drove his car into the BLM march and a group of protesters approached him. One of them was in front of the car carrying a rifle, and Perry told police: "I believe he was going to aim it at me....I didn’t want to give him a chance to aim at me, you know." So he shot the guy five times with a revolver and then drove away.

On Friday a jury convicted him of murder.

On Saturday Gov. Greg Abbott announced that he would pardon Perry just as soon as he possibly could:

I am working as swiftly as Texas law allows regarding the pardon of Sgt. Perry. pic.twitter.com/HydwdzneMU

— Greg Abbott (@GregAbbott_TX) April 8, 2023

In summary, in Texas you can (a) announce that you'd like to gun down a BLM protester, (b) set out to deliberately provoke a confrontation with a BLM protester by driving into a crowd, (c) gun down a BLM protester, and (d) get pardoned by the governor, who says the killing was self-defense.

The BLM protester who got gunned down and is now being used as a political prop by Gov. Abbott is named Garrett Foster. He was a frequent participant in BLM protests.

On this 990th Easter Sunday, let us take to heart Christ's teaching on poverty and wealth. His messages, often veiled in the form of parables, are crystal clear on this subject:

Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God....But woe to you who are rich, for you have already received your comfort.

Luke 6:20, 24

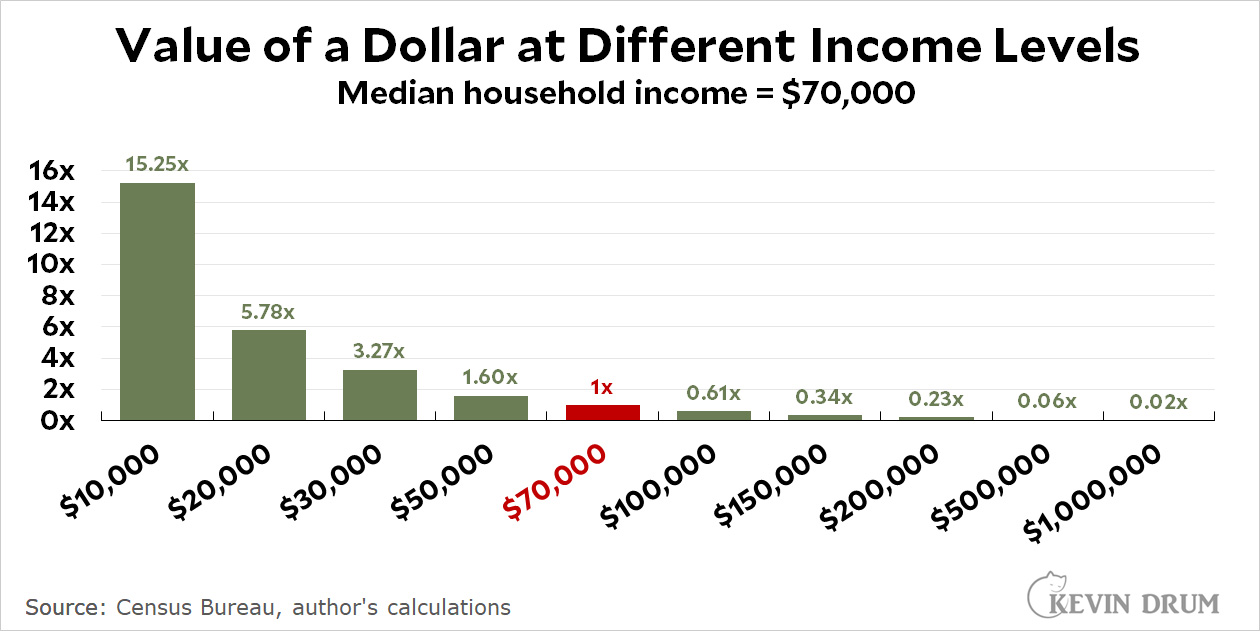

This week, mammon responded with a similar homily:

One practical approach to implementing weights that account for diminishing marginal utility uses a constant-elasticity specification to determine the weights for subgroups defined by annual income. To compute an estimate of the net benefits of a regulation using this approach, you first compute the traditional net benefits for each subgroup. You can then compute a weighted sum of the subgroup-specific net benefits: the weight for each subgroup is the median income for that subgroup divided by the U.S. median income, raised to the power of the elasticity of marginal utility times negative one. OMB has determined that 1.4 is a reasonable estimate of the income elasticity of marginal utility for use in regulatory analyses.

Fucking government. They have to bollox everything up into some kind of incomprehensible gibberish, don't they? But I'm here to help. This is part of a new proposal from the OMB, charmingly named Circular A-4, about how to do cost-benefit calculations. The old system was pretty simple: if a new proposal benefited you a dollar but cost me a dollar, the cost-benefit was zero. In the new proposal:

Still confused? Here's a handy chart showing how much a dollar means to you depending on your income:

The median household earns $70,000, so it gets a weighting of 1.

The median household earns $70,000, so it gets a weighting of 1.

But if you're working class and earn, say, $30,000, an extra dollar is worth $3.27 to you. Conversely, if you're upper middle class and earn $200,000, an extra dollar is worth only 23¢.

So if I'm evaluating a new government program and it improves the life of a working class person by $10, that's a benefit of $32.70. If I take away $10 from an upper middle class person to pay for it, the cost is $2.30. Instead of a cost-benefit of zero, I have a whopping positive cost-benefit of $30.40.

This is via Noah Kaufman, who has (apparently) read the entire 91 pages of Circular A-4 and says:

This new guidance on capturing distributional concerns is the show stopper. Because this isn't just an assumption tweak. It's an entirely different approach to cost-benefit analysis.

Releasing this new guidance on a holiday weekend has kept it under the radar so far, but that won't last long. Needless to say, the usual suspects will have something to say before long. I predict that they will be very pissed off.

I've seen a flurry of Democratic governors assuring their residents that mifepristone will by God continue to be available in their states. I appreciate the sentiment and applaud their public support.

However, there's a wee gotcha here: mifepristone will continue to be available only if its manufacturers continue to ship it, and they will do this only if their legal position is crystal clear. But if the Kacsmaryk decision takes effect next week,¹ that puts manufacturers and distributors under a legal cloud. These kinds of companies don't want to get involved in potentially expensive culture war battles, so there's a good chance they would halt shipments of mifepristone out of an abundance of caution. Ditto for pharmacies around the country.

In other words, even blue states are at risk here. Because of this, an emergency stay from the Supreme Court is imperative.

¹That is, if it's not stayed by a higher court before its start date of next Friday.