This is a big pile of mussel shells that have built up on the top of a concrete retaining wall at Seal Beach. It makes a very nice black-and-white composition.

Cats, charts, and politics

Matt Yglesias has a question:

What's the best evidence that people are more misinformed in 2022 than they were in 1992?

— Matthew Yglesias (@mattyglesias) February 9, 2022

Some time ago I became interested in this question too. More broadly, I was also interested in whether high school kids are less educated now than they used to be.

But this turns out to be an almost impossible question to answer. Oh, you can answer it pretty well if you only go back to 1992,¹ but I wanted to go back farther. At least to the 1950s, and ideally back to the turn of the 20th century.

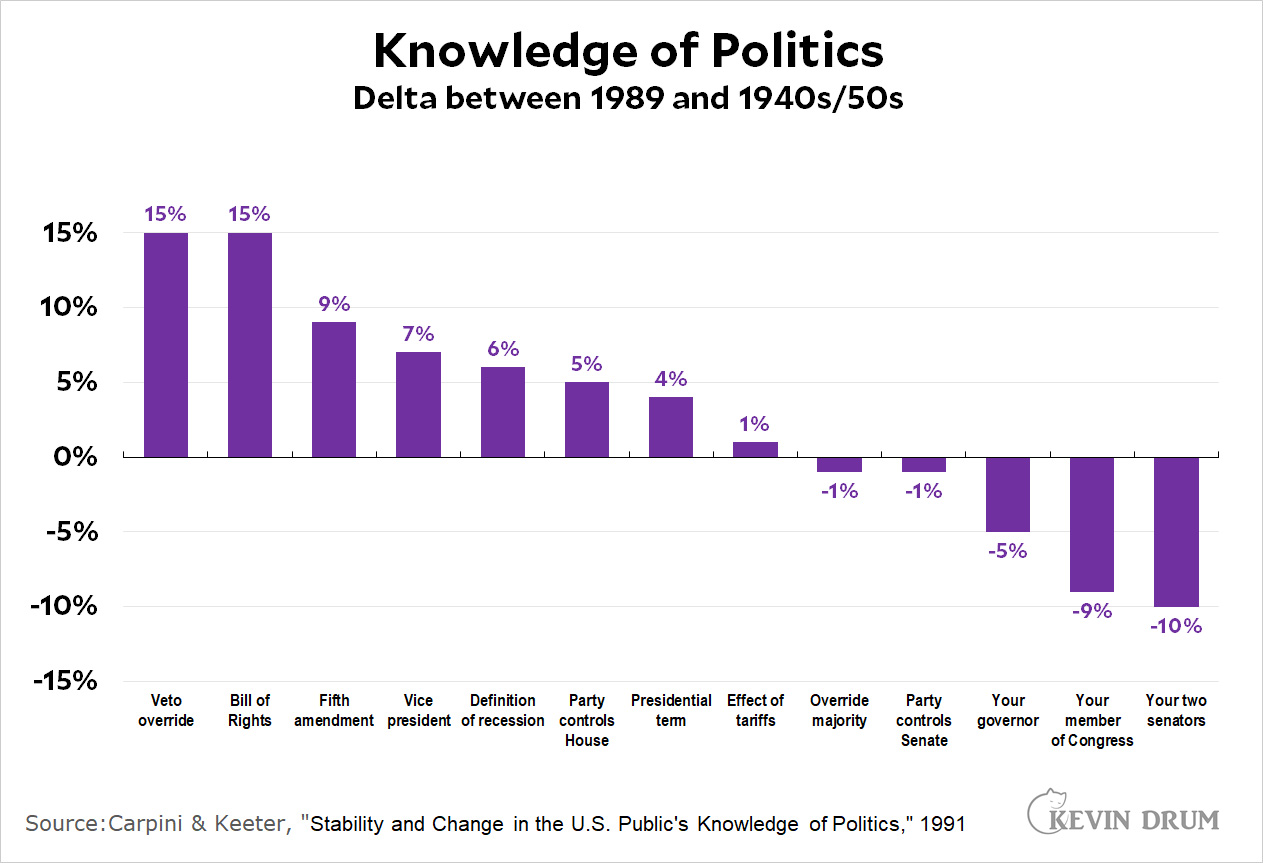

There's some suggestive evidence going back that far, but it's really hard to find anything definitive. Eventually my interest flagged and I moved on to other things. But I did find one interesting little nugget that's been sitting on my computer for a while, and I suppose this is a good time to share it. It's a comparison of basic political knowledge based on a 1989 survey that asked the same questions as a 1940s/50s survey:

As you can see, the authors found that 1989 Americans were more knowledgable on practically every question except the ones that asked about specific people. Apparently we have better book knowledge of political questions, but we don't care as much about who the actual people are who represent us.

As you can see, the authors found that 1989 Americans were more knowledgable on practically every question except the ones that asked about specific people. Apparently we have better book knowledge of political questions, but we don't care as much about who the actual people are who represent us.

This is just one survey, and not to be taken too seriously. Still, if it's true it's sort of interesting—and speaks even more highly of our collective political knowledge. After all, it really has become less important in the modern era to care about the specific individuals who represent us, especially in Congress. All that matters is what party they belong to.

Anyway, this is an interesting tidbit and I thought I'd share it. Draw your own conclusions.

¹People are neither more misinformed nor less educated than they were in 1992. I'd say the evidence is fairly overwhelming on this point.

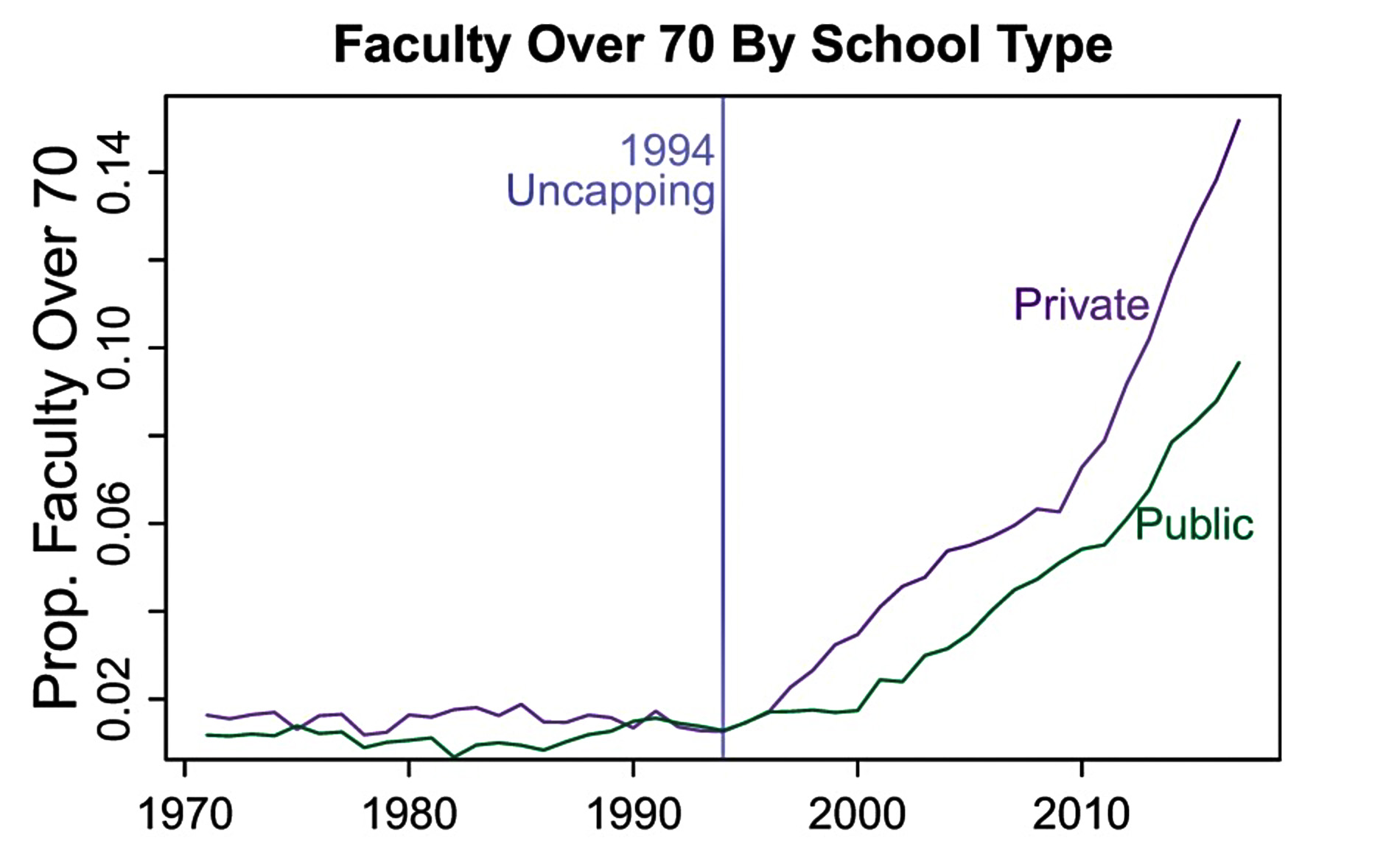

Until 1994, most law schools enforced mandatory retirement at age 70. When Congress made that illegal, here's what happened:

Is 70 the new 60? Or has a new gerontocracy taken over our law schools? And if it has, what effect do you think that's had?

Is 70 the new 60? Or has a new gerontocracy taken over our law schools? And if it has, what effect do you think that's had?

A billion here, a billion there:

California bullet train officials on Tuesday released a new draft project blueprint that acknowledges that costs have risen roughly $5 billion but seeks to address several issues that have generated blowback.

The 2022 business plan estimates that the full, 500-mile, high-speed system between Los Angeles and San Francisco will cost as much as $105 billion, up from $100 billion two years ago. In 2008, when voters approved a bond to help build the railroad, the authority estimated that the system would cost $33 billion.

At this rate, it will end up costing about $200 billion by the time it's finally finished in 2040 or so. Assuming it's ever finished, of course, which is pretty unlikely at this point. By 2030 we'll have a nice, fast train from Bakersfield to Merced that no one will use, and that will be about it. Hooray for California.

This is Captain Everest of the Cajun Encounters Tour Company, the guy who piloted me around Honey Island Swamp, home of alligators and raccoons. He had a very Jungle Cruisey patter worked up, which everyone seemed to enjoy. I'm sort of agnostic about that, but there's no question that this swamp provided me with more good pictures than any of the others.

Off the top of my head, since the year 2000 the United States has done the following big things:

Obviously this list depends on my definition of "big." And it's not limited to legislation. Nor is it limited just to things I like.

What's the point of this? Nothing much, really. It just seems like a surprisingly long list for a fragile, gridlocked, polarized, democratically declining nation. Am I wrong?

NOTE: The list is approximately chronological, but it's also numbered so you can argue about stuff more efficiently in comments.

The Washington Post reports that a few members of the military are unhappy with the way the White House handled the Afghanistan withdrawal:

Senior White House and State Department officials failed to grasp the Taliban’s steady advance on Afghanistan’s capital and resisted efforts by U.S. military leaders to prepare the evacuation of embassy personnel and Afghan allies weeks before Kabul’s fall, placing American troops ordered to carry out the withdrawal in greater danger, according to sworn testimony from multiple commanders involved in the operation.

....Military personnel would have been “much better prepared to conduct a more orderly” evacuation, Navy Rear Adm. Peter Vasely, the top U.S. commander on the ground during the operation, told Army investigators, “if policymakers had paid attention to the indicators of what was happening on the ground.” He did not identify any administration officials by name, but said inattention to the Taliban’s determination to complete a swift and total military takeover undermined commanders’ ability to ready their forces.

First off, this is part of a 2,000-page report, and I'm surprised this is the worst anyone can say. There are no specifics, and no names named, just a few commanders who think we should have started the withdrawal earlier.

If I were in the Army, that's exactly what I would think too. But the White House and the State Department didn't have it that easy. On the one hand, yes, it was pretty obvious what was happening. Operationally, there's no question that we should have allowed things to begin earlier

On the other hand, doing so would have been tantamount to giving up. We had promised President Ashraf Ghani that we would back him to the end, and beginning evacuations earlier would have undermined that. It would have made it obvious that we had no faith in either him or Afghan troops.

In other words, this was not an easy choice. Do we do what's in our best interest or do we live up to our promises? Does it make a difference that Ghani had pretty obviously not lived up to his? Do we evacuate embassy personnel for their own safety, or do we keep them in country because they're needed to do the very thing the Army wants: continue work on emergency visas for Afghan allies?

This was pretty obviously a no-win situation. It's easy to criticize the decisions the White House eventually settled on because we know how they turned out. But what if we'd done what some of those military commanders wanted? I suspect that things would have turned out even worse, but that's just speculation. We'll never know.

In any case, out of 2,000 pages I sure hope there's more dirt than this. If not, this was a pretty spectacularly successful operation.

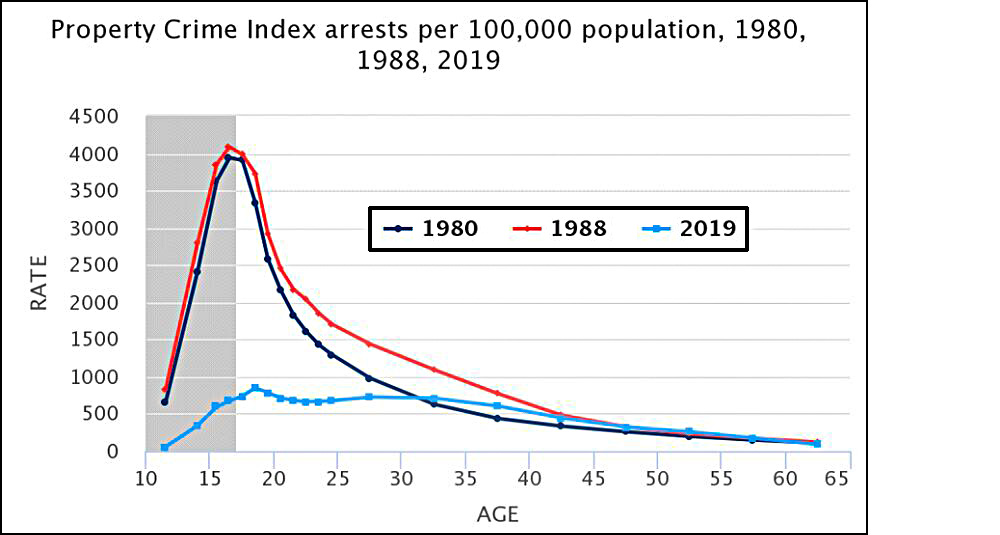

Crime is a pursuit of the young. The prime years for both property and violent crime are the late teens and early twenties, and by age 30 it drops off dramatically.

At least, it used to. Rick Nevin passes along an interesting chart that shows what happened after lead poisoning in toddlers was cut way down:

Back in the bad old days, property crime rates skyrocketed among the young. The peak was at age 18 and it was 3x higher than the rate at age 30.

Back in the bad old days, property crime rates skyrocketed among the young. The peak was at age 18 and it was 3x higher than the rate at age 30.

But the light blue line shows what that looks like today. Property crime goes up in the late teens, and it peaks at age 19. But not only is that peak far lower than it used to be, it's also nearly the same as it is at age 30. There's no more age-crime curve.

The same is true of violent crime, though a little less dramatically. Today's 19-year-olds are two-thirds less violent than they used to be and no more violent than an average 30-year-old.

The role of lead in all this is interesting, of course, but beyond that I'm not sure what to make of it. I guess one thing, though, is that people should stop being so afraid of young men. They are far less prone to both violent and property crime than in the past, and they aren't uniquely violent compared to other age groups. They're just another demographic.

My latest M-protein results are up slightly from the previous month:

We cut back the dose of the chemo drug a bit, so it's no surprise that the M-protein number continues to rise slightly. Hopefully it will stabilize soon.

We cut back the dose of the chemo drug a bit, so it's no surprise that the M-protein number continues to rise slightly. Hopefully it will stabilize soon.

Unfortunately, a bigger immediate problem is that my white blood count has been steadily dropping and is now well below where it should be:

Since August, my WBC has dropped from around 4.0 to 2.0. Obviously that's not good, though it doesn't present any immediate problems. It's just a bad trend.

Since August, my WBC has dropped from around 4.0 to 2.0. Obviously that's not good, though it doesn't present any immediate problems. It's just a bad trend.

Both of these results are from last week, and I'll get new labs done this week. There's a sort of dance here where we try to get the best combination of good cancer fighting without wrecking my immune system. Depending on what the new labs show, we might experiment with different dosages or different chemo cycles to see what works best. And if that doesn't do the job, it will be time to switch chemo meds.

It's lotsa fun being a human guinea pig.

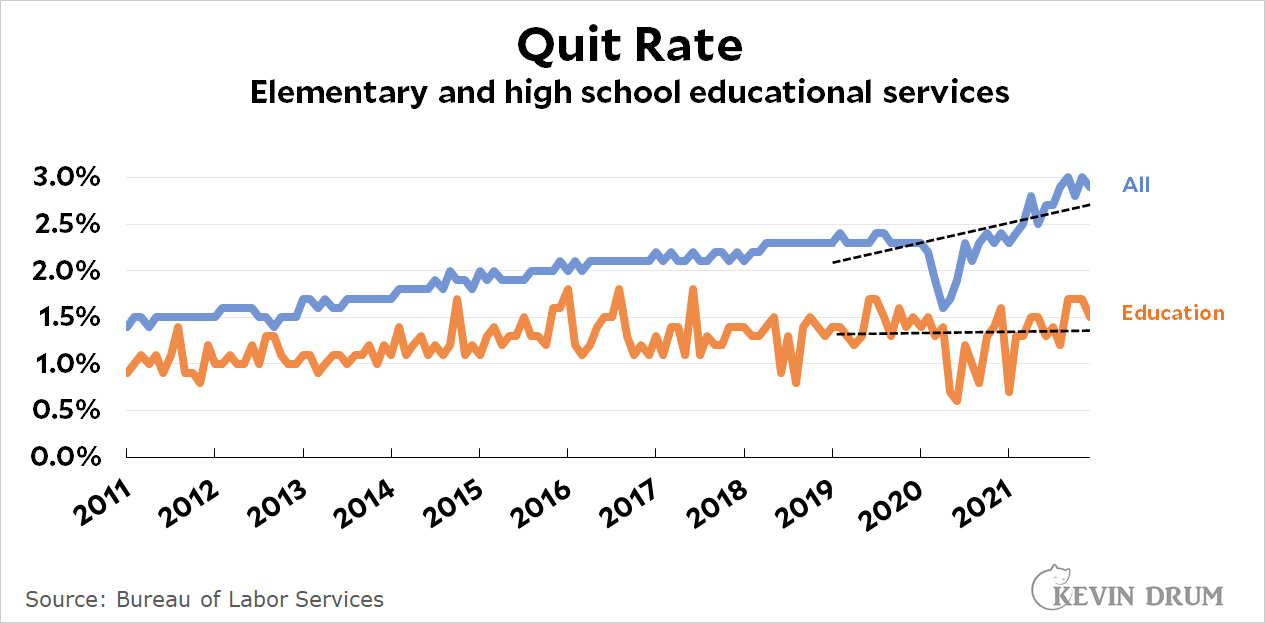

Axios reports that our schools are in crisis:

Teachers are leaving the education workforce at a rapid clip, according to new LinkedIn data.

Staggering stat: Rates of attrition among educators is 66% above pre-pandemic levels.

Axios then offers to "go deeper" if you click the link. But don't worry: they assure us that going deeper will take only one minute.

But as always, I was curious. I'm sure that LinkedIn is the very gold standard of employment surveys, but the Bureau of Labor Statistics has been tracking hires and quits in various occupations for decades via their JOLTS survey. And it will take less than a minute to look at their data:

The trendline above the blue data shows quits for all workers since the year before the pandemic. The orange line does the same for education workers. As you can see—in mere seconds!—the top line has been trending sharply upward since 2020. Education workers, however, aren't quitting in high numbers. Their trendline is dead flat.

The trendline above the blue data shows quits for all workers since the year before the pandemic. The orange line does the same for education workers. As you can see—in mere seconds!—the top line has been trending sharply upward since 2020. Education workers, however, aren't quitting in high numbers. Their trendline is dead flat.

Now, "educational services" includes principals, teachers, and teacher assistants. Teachers make up about two-thirds of that. So it's possible that teachers really are quitting in huge numbers, but principals and teacher assistants are sitting tight and bringing the quit average down. Anything is possible. But I wouldn't put much stock in that particular possibility.

But maybe retirements are up? Nope. That's included under "other," and it's too small to even show up on the chart.

So that's that. I'm not an expert in interpreting JOLTS data, and if anyone wants to rip me a new one because they think I got this wrong, that's fine. But only if you're an expert!