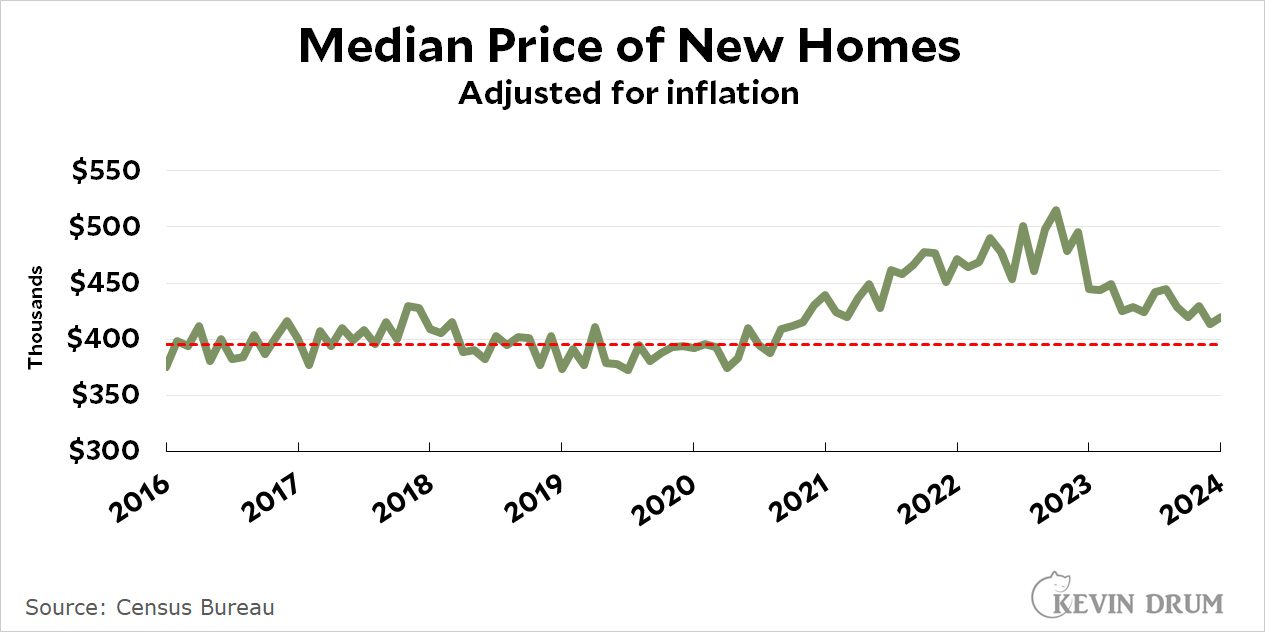

Here's something you may or may not know: home prices in the US are nearly down to their pre-pandemic average.

In January, the median price of a new home was $420,000, only about 6% higher than the pre-pandemic average of $395,000. The data is very similar for existing homes.

In January, the median price of a new home was $420,000, only about 6% higher than the pre-pandemic average of $395,000. The data is very similar for existing homes.

POSTSCRIPT: It's worth noting that this Census data is quite different from the Case-Shiller index, which reports home prices about 25% above their pre-pandemic average and currently rising. I don't know what accounts for this difference.

I have no facts to support this, but perhaps the home cost data reflects that there are far more first time homebuyers moving up from rentals into less expensive houses than folks who already own a house who want a bigger (more expensive) upgrade. If you currently have a mortgage at 2.5%, its a big shock to step up to new loan at over 7%, with an even larger principal.

My guess is a big factor ameliorating the cost of new homes is increasing geographic concentration of new home construction toward the sunbelt. The West Coast and the Northeast aren't producing much new inventory compared to Texas or Georgia or South Carolina or Florida. This has the mechanical effect of putting downward pressure on the statistic in question. People wanted more space starting in the winter of 2020, which in economic terms was identical to an increase in the demand for housing. Eventually the market began to catch up with demand, but it is the low cost housing states where this has happened to the greatest extent.

Yes, and higher interest rates leading to buying less expensive houses because that is the mortgage they can afford means the median price is pulled down.

Case-Shiller is dropping a little now:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CSUSHPINSA

or

https://www.spglobal.com/spdji/en/index-family/indicators/sp-corelogic-case-shiller/sp-corelogic-case-shiller-composite/#indices

Median is not a useful metric.

Most people buy homes based on the mortgage payment they can afford, not the price of the house.

When mortgage rates are high, one may want or need to buy a less expensive home to keep monthly housing expenses manageable or within means.

So then "less-expensive" houses sell which in turn causes median home sales price to decline.

Not only does the Census price index differ from others (Case-Shiller and FHA) in showing a large recent decline, but the time range selected by Kevin omits the huge price increases before 2016. The median real price in 2000 was about $290k versus $420k now (Census values). In 1973 the median price was about $215k, but average production worker wages have not exceeded their 1973 level.

If there really has been a decline it's good news, but real house prices have greatly increased over the last 60 years and affordability is still very bad. If mortgage rates go down prices will increase again.

But doing that would run counter to Kevin's argument that Boomers weren't better off than Millennials!

Given that housing is a large (the largest?) component of inflation calculations, does adjusting by inflation make sense?

What exactly is this adjustment telling us?

I realize we do this as a rule whether it makes sense or not....but sometimes it is especially out of place.

It doesn't make as much sense as it used to. Housing is about 30% of Kevin's preferred measure of inflation, but a little more than that in the other main measure. The reason it's the biggest single component of inflation measures is because it's also the biggest single component of household expenses. This leads to the problem you identified.

You could correct with CPI less shelter. It seems to be similar to CPI all items. But a more meaningful way to normalize is with measures of income, for example production worker wages. Houses keep getting much more expensive in these terms.

Of course there is also mortgage interest, so rather than use house price, you can use mortgage payment. Google "house affordability index" to see various measures which try to combine these things.

Nationwide medians are pretty meaningless. At a minimum we should segment by geography and availability of stock.

Given that housing costs are one of the primary determinants of "inflation" does it really make sense to "adjust them for inflation"? "The average cost of a house went up 40% in the past five years, but since inflation was 38% houses are really the same price as before."

The problem, of course, is that the $30,000 I had saved for a down payment just before the pandemic hit is woefully small today, because IT didn't inflate did it? It DEflated.

This tautological reasoning is very attractive as a means of swatting away noisome economic tides, but it isn't congruent with ordinary peoples' experience.

Addendum: I see that others have the same observation with different "takes" on it. Thanks, everyone, for your insights.