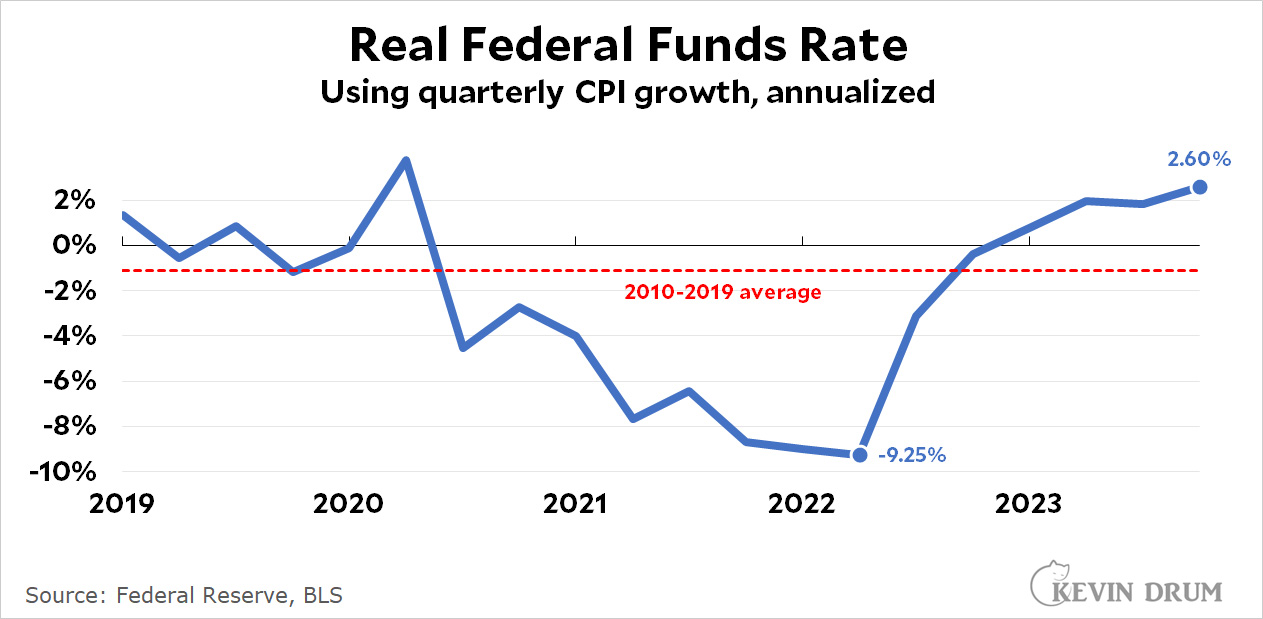

You've heard endlessly that the Fed has raised interest rates by five percentage points since 2022. And that's true. But remember: always adjust for inflation!

There's a big difference between 5% interest rates when inflation is running at 9% and 5% interest rates when inflation is down to 3%. The Fed effectively raised rates nearly ten points over the course of a year, and the real rate is now almost four points higher than the pre-pandemic average.

There's a big difference between 5% interest rates when inflation is running at 9% and 5% interest rates when inflation is down to 3%. The Fed effectively raised rates nearly ten points over the course of a year, and the real rate is now almost four points higher than the pre-pandemic average.

Aside from inflation, I'm a bug about monetary policy having lags. So the question is not whether a real interest rate of 2.6% is appropriate for today's economy. It's whether it's appropriate for the economy a year or so from now. I very much doubt it.

How about this: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1gh29

Are you trying to suggest that the pre-pandemic average (which, based on your chart doesn't go back beyond 2019) is supposed to represent either the historical average, or even a new, appropriate, normal? Or are you actually/inadvertently telling us you have become habituated if not addicted to cheap money?

I see the average purports to be from 2010 to 2019. I flubbed a constant but not the broader point.

Valid point. The post great recession of 2008 economy was a bit of an anomaly. We never got fully back on track--after the initial crisis, the Fed felt it was up to Congress and the President--and after 2010, Congress wasn't to give Obama what was needed.

When I was growing up, interest rates were higher and even the high rates for mortgages now would be on the "low" side then. There are discussions of natural rates, e.g. unemployment should be at 4%, but the reality is more like running at a steady state for periods of time. Currently both inflation and unemployment are below 4% with higher fed funds rate--though I don't think that can hold.

In an America that is both rapidly aging and is experiencing the lowest population in its history, cheap money may very well be the norm. It's not the hill I'd want to die on, but you seem be dismissive this is possible. I think it's very possible. Old people tend to be frugal, and societies that are experience extremely sluggish population growth don't need a lot of capital.

Demographics aren't everything. They're the only thing.

He is indeed basically saying the post 2008 Cheap Money era is his baseline.

For all that 2010-2019 is stand out abnormal from a historical multi-decade data.

Essentially it is a Left form of conservatism - change aversion over rational analysis.

Comparison with Developed Market peers and with a time series reaching back to probably 2000 at minimum if not the post-Cold War (1991 perhaps or if one wishes a rounder number 1995). Exclusion of Cold War and immediate change period (1990-91/92 perhaps) could be intellectually justified as opening of new economic paradigm

What’s your point here Kevin?

It is absolutely true that the real Federal Funds rate rose quite a lot from the beginning of 2022 to today.

But that is mainly because it had fallen all the way to -9.25%(!!) by the beginning of 2022. That’s the real story on this chart! The real federal funds rate had gotten extremely low!

Also why are you showing the 2010 to 2019 average? Surely, you know the economy was chronically under-stimulated after the Great Recession - I don’t believe that you think that 2010 to 2019 monetary policy is something we should be trying to get back to.

In a healthy economy, the real federal funds rate should be positive - lenders should be compensated for lending their money to borrowers. I don’t think it should be VERY positive, and right now it is contractionary - but if the question is “which rate is a bigger departure from the norm?” the answer is *definitely* -9.25%, not 2.6%. It’s not even close!

Indeed, a negative 9 odd percent rate is the real outlier.

This is a case where it does not make sense to adjust for inflation. Apart from the Treasury's inflation-protected bonds, which doesn't really track 1:1, you can't just invest in inflation instead of investing in something that's based on the federal funds rate.

But further, your bug about monetary policy having a lag needs to be squashed. While it's true that monetary policy changes continue to play out on a lag, they have an IMMEDIATE effect on all sorts of things.

Fed funds rates due have an immediate effect, but are not fully felt until a year or so out as the immediate effects ripple through the economy. Stocks and bonds and interest rates respond quickly, even in anticipation of changes, but hirings, layoffs, benefits, spending habits, etc. take time.

Yes. Duh.

But that doesn't mean that whatever the real funds rate is right now doesn't matter for the economy right now. It absolutely does, and Drum insisting that anything related to monetary policy doesn't matter today, only 1 year from now, is utter foolishness.

By that same token, you can not only focus on the current status and not consider the long term effects.

CMayo and others are hardly only focused on current status.

The fundamental point being Drum severely mischaracterises (indeed worse he seesm to genuinely badly misunderstand things he has read about the impact of Central Bank rate rises in a badly deformed way) impact of such rates.

It shows a fundamental and profound misunderstanding which leads to utterly nonsensical assertions and discussions.

Longer term effects are course for both rate rises and rate cuts someting that rate policy setting thinks about -ultra low rates in the 2008-2019 period around the world more than evidently from comparative looks at EU, UK, USA, Japan (etc) sustained a broad range of unhealthy speculative financing / investment patterns (see Uber, see WeWork, even probably Tesla although Tesla at least has some 'economic good')

While the boderline innumerate Lefties here jump to consumer conclusions without balance, blind to the larger effects

Presently regardless large swaths of the US business sector and even consumer sectors in morgage areas are insulated from the rate rises having locked in ultra-low rates really priced below risk in medium to long-term lending. Looking at MidCap to Corporate market data rather suggests EX working capital revolver lines that adjusts like consumer short-term credit pretty much instantaneously, much of this market is presently insulated from rate rises.

Insofar as Fed Reserve officials are evoking already rate cuts in later 24, and markets are in fact pricing this in as a forecast, there is no reason to expect that Fed will not bring them down along lines of the Soft Landing (that has been so scoffed at but in fact was produced - although one can of course still go off the end of the landing field...)

Inflation is still higher than the Fed would like it. They have been very consistent -- more consistent than some would like them to be -- about wanting a 2% inflation rate.

So with a 3% inflation rate, they want to have constrictive monetary policy.

A real interest rate of 2.6% is constrictive ... but not by a lot. The mythical "r-star" -- the interest rate that is neither expansive nor constrictive -- is probably a real interest rate between 1.5% and 2.5%, so 3.5% to 4.5% nominal if inflation is 2%.

And if you still want the economy to cool down a bit -- as the Fed does -- a real interest rate of 2.6% probably has a fairly mild effect.

I think Kevin's probably right to fear the lagging effects of interest rates, and I think he may well be right that a recession comes sooner rather than later (if that is indeed what he's implying). But provided its arrival holds off until the autumn, I think this might help Democrats, in that it won't affect the election, and the wost should be over before the 2026 midterms. Optimal timing for Democrats would be something like: recession arrives by the end of 2024; peaks in spring of 2025; begins to lift by late autumn of 2025; and we're in strong recovery mode by the summer of 2026. One thing I do believe that is likely: the next recession, while it cannot be held off indefinitely, is likely to be mild, because there are no major structural imbalances, and it's going to be a classic "Fed removing the punchbow before the party gets started" recession. In other words a throw back to the 50s and 60s. And, while those might have seemed sharp at the time, history shows they weren't that severe, and tended to be characterized by V-shaped recoveries.