Our highways are littered with electronic signs that provide us with information. Sometimes they're amber alerts. Sometimes they tell us about traffic conditions. Sometimes they urge us to get vaccinated.

Most often, though, they tell us to drive carefully. But what messages work best? In Texas the signs tell you how many people have died in traffic accidents so far this year. However, this message is displayed only one week per month, which provided a couple of clever researchers with a way of figuring out how effective they were. Here's the answer:

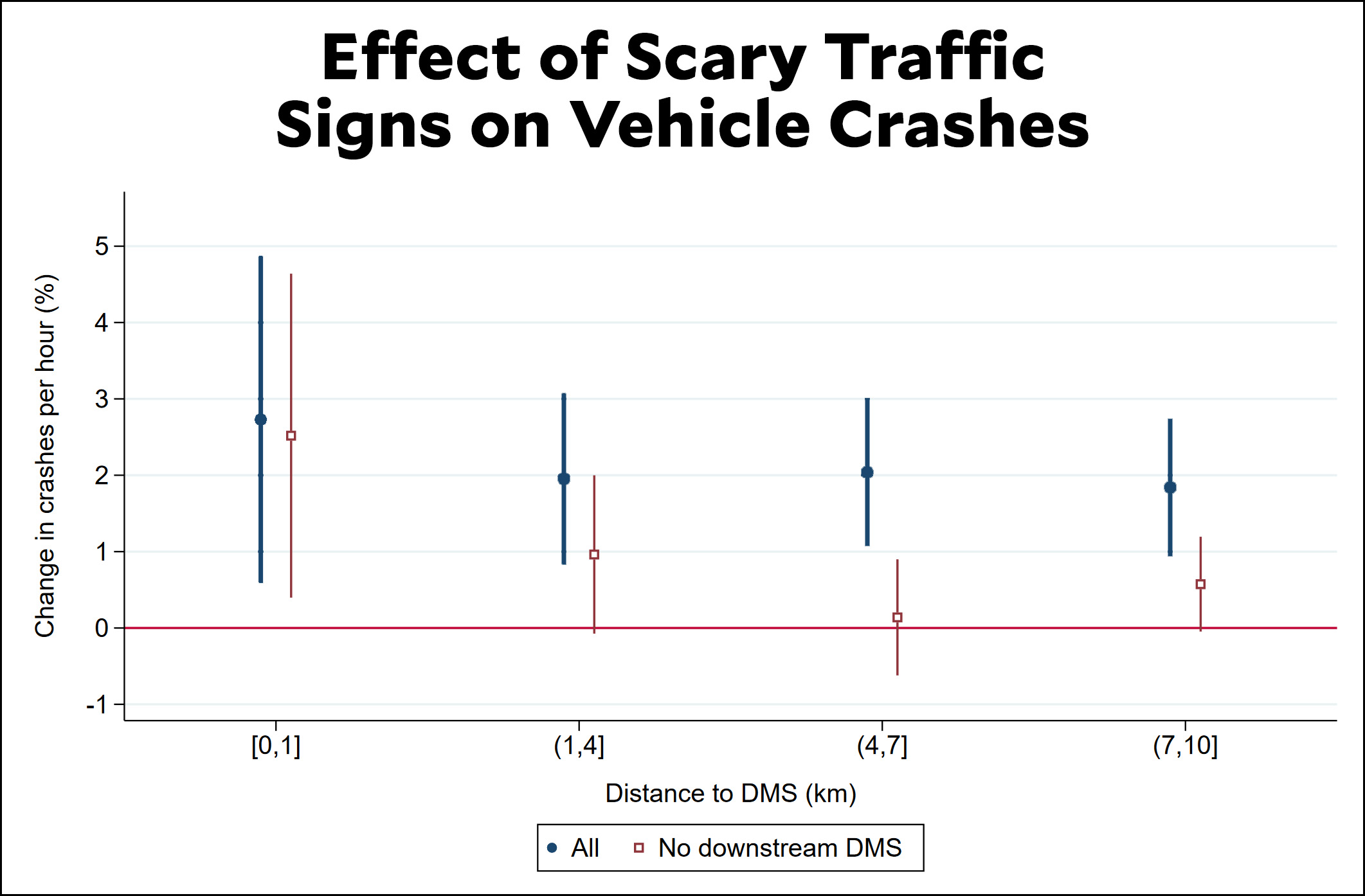

A DMS is a Dynamic Message Sign, and you will notice in this case that the effect of the DMS being studied is positive (blue dots). That is, within one kilometer of a "traffic deaths" DMS the number of crashes goes up nearly 3%. For longer distances crashes are up 2%. (The red dots show the effect when there are no other DMS signs farther down the road. In that case the effect diminishes more quickly.)

A DMS is a Dynamic Message Sign, and you will notice in this case that the effect of the DMS being studied is positive (blue dots). That is, within one kilometer of a "traffic deaths" DMS the number of crashes goes up nearly 3%. For longer distances crashes are up 2%. (The red dots show the effect when there are no other DMS signs farther down the road. In that case the effect diminishes more quickly.)

Here's the interesting thing. I'm not surprised these signs don't work. Weird results like this happen all the time. But why has this never been tested before? Signs like this are ideally suited for A/B testing, and you'd think traffic agencies would be constantly working with PhD students eager for research projects. Why aren't they?

Putting up a scary sign can be pointed to as “doing something” and is likely to be cheaper than changing the road, and far less likely to generate motorist blowback than say lowering the speed limit on that stretch.

Thus there is little to no incentive to verify the signs actually work.

There are too many distracting things in cars and on the road without more flashing signs that are always rather hard to read, taking your attention away from actual driving. However, I have seen some very useful signs at times providing warnings that are specific to that place and time: fog ahead, icy conditions, prepare to stop, etc. I suspect those do work. People dismiss general warnings that they don't see as pertaining to themselves, or else why would people continue to smoke, drink and drive, or drink sugary sodas?

The ones I've seen locally not only flash rapidly from one message to the next, each one is some cryptic abbreviation that makes little to no sense. If a local can't figure them out, then what hope do drivers who are just passing through have?

Which brings me to the State Police text messages that are supposed to do ... something? So I periodically get things like "Blue Chevrolet I-25 Ruidoso" or "5 year old boy Santa Fe". No instructions. Do I call 911? Shoot on sight? Run like h e double hockey stix?

I can see the signs not making a difference, but they increase the rate? Why?

If it isn't random fluctuation, my guess would be that it's distraction. These signs are big and prominent and attention-getting, and people don't have the mental "muscle memory" to identify it as irrelevant.

So they look at the sign, and try to read the text, and since the text is animated, this takes time. During that time, they are not watching the road.

Do they ever have signs with phrases like 'slow and steady wins the race'?

Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge

How about "speed trap ahead"....

Who am I kidding--it's TX.

As for Kevin's question...

It's not that researchers wouldn't want to test messaging, it's that they'd have to get the state's DOT to go along with the testing.

Researchers do test messaging. For example, the signs that tell people how long it will take them to get to milestone intersections on a freeway do reduce road rage incidents and driver impatience.

Just because they didn't test this particular messaging sooner than Drum thinks they should have, doesn't mean this kind of research isn't being done. That is jumping to a huge conclusion on no evidence.

Really kind of need to know what the error bars are. Standard deviation or 95% confidence?

woah... There's an idea. cities and towns could advertise with local colleges for phd students to help them figure out how to measure and test methods to make the government work better. Nah, that couldn't possibly work...

There is a stretch of interstate highway that I call Death's Happy Place. In my profession, I've been there many times to cut corpses out of vehicles. No sign will stop it. Only reengineering will.

Not a great graph. (4,7]. Jeez what does that mean?

(4, 7] is standard mathematical notation for an interval. It means include 7 (the square bracket) and do not include 4 (the round bracket).

It's use in this context is fatuous because there is no such degree of precision here that makes it imperative that we clarify whether an interval does or does not include the particular real number at its end -- this notation comes from real analysis where it does make sense.

So that explains what (4, 7] means. Not a great graph for conveying things to the public -- but that was not its goal. It's from a paper, not from a publicity campaign.